INTRODUCTION

The growth of Internet usage has changed the way we plan our tourism. It is now used, not only as a viewing medium that displays the features of the accommodation, but also to gather user opinions on the potential destinations (Buhalis and Law 2008;Cox et al. 2009;Anderson 2012). According to the TripBarometer (TripAdvisor 2016), of the 36,444 travellers polled across 33 countries, 73% used online sources to decide on their destination and 86% used them to decide on their accommodation. The importance of online opinions is also highlighted in the TripBarometer 2017/2018 (TripAdvisor 2018), which states that 86% of travellers would not book accommodation without having previously read relevant opinions. This all means that hotel establishments have a greater stake in managing their online reputations than ever before.

Considering that lots of us depend on reviews from other consumers to assess the quality of goods and services (Wirtz and Chew 2002), electronic Word-Of-Mouth (eWOM) in the form of an online review has an especially important influence in both the tourism industry and the accommodation sector, where the value of intangible products is difficult to assess prior to their consumption (Litvin, Goldsmith and Pan 2008;Xie, Chen and Wu 2016).

Users can find several Internet forums where they can read online reviews about hotels: (a) the websites of the hotels; (b) third-party websites for the online reservation of accommodation (for example Booking.com, Expedia.com, Agoda.com, etc.); (c) hotel comparison websites (such as Tripadvisor.com, Trivago.com, Kayak.com, etc.); (d) websites that provide accommodation-related advice; (e) social network pages of the hotel establishments (such as Facebook, Twitter, etc.). These reviews mean that potential customers are being influenced by third-party information over which a hotel has no direct control.

The credibility and the bias of opinions expressed on Internet pages will depend on where they have been posted, since their veracity is not checked in all forums (it is not always compulsory to have stayed in a hotel to voice an opinion, for example, and negative commentary will also be censored on some webpages). Furthermore, depending on the average score system (licensed software providers, such as ReviewPro or TrustYou; metasearch websites, for example Trivago or Kayak; or third-party online reservation of accommodation, such as booking.com), there are important differences not only in the rating scores obtained by the hotels, but also on the rankings in which the hotels appear when undertaking a search (Mellinas and Reino 2019).

Nevertheless, these online opinions represent one of the fundamental elements of online reputation, so if hotels wish to improve their reputation, it is especially important for them to monitor such opinions and to manage them (Phelan, Chen and Haney 2013;Aureli and Supino 2017;Schuckert, Liu and Law 2016;Tran, Ly and Le 2019). In most cases, reviews are public and permanent and, when positive, they might attract future clients and increase sales (Ye et al. 2011;Anderson 2012). But, if negative, they could induce the opposite effect and even neutralize a certain number of positive comments. However, this effect could in turn be mitigated when there are very many reviews (Cunningham et al. 2010;Melián-González, Bulchand-Gidumal and González 2013).

However, despite the importance of online reputation, little is known about how hotels publicize it on their official websites, at a time when the direct booking wars between hotels and Online Travel Agencies (OTAs) are growing and beginning to shift towards hotels, which have recovered a market share of direct bookings. In that sense, Kalibri Labs (Green and Mazzocco 2019) found that there was indeed a shift in consumer behaviour toward Brand.com sites versus OTAs, such as Booking.com or Expedia. More consumers than ever before are choosing direct bookings rather than booking on a third-party site. In particular, Brand.com has consistently generated 50% more bookings on average to hotels in the United States of America than the OTA channel. In Spain, the leader in online booking in 2019 was Booking.com, while Expedia moved up to third place, because Brand.com sites managed to unseat it and move into second place (SiteMinder 2020). More specifically, direct hotel bookings in Spain have grown 113 percent from 2013 to 2017, indicating a closer relationship between Spanish hotels and their guests (SiteMinder 2018).

Therefore, the hotels are at a key moment in time to continue recovering ground in direct bookings, showing their prices and, at the same time, information on their online reputation, so that potential customers feel no need to consult other Internet forums. Considering the advantages of hotels publicizing their online reputation on their official websites, our objective is to shed light on how the hotel sector is performing in this regard. Likewise, possible variables are analysed that could be related to publicity and both the type and the source of the ratings that are obtained from client opinions. The paper intends to contribute to academic literature, by examining whether hotels are adapting to the new competitive environment of online sales, their willingness to use external sources and to publicize their online reputation and which characteristics of hotels may favour this adaptation.

1. CONCEPTUAL BACKGROUND

Research in the online reputation management has been focused on analysing the role of online opinions in the decision-making process for accommodation and estimating the market share (Sparks and Browning 2011;Öǧüt and Taş 2012;Duverger 2013;Zhao et al. 2015), the factors that make these opinions useful (Liu and Park 2015;Fang et al. 2016), the effects of different rating systems (Mellinas, Martínez María-Dolores and Bernal 2016;Mariani and Borghi 2018;Casaló et al. 2015;Xie, Chen and Wu 2016), their reliability and credibility depending on the source (Schuckert, Liu and Law 2015;Gössling et al. 2019;Gellerstedt and Arvemo 2019), and even the factors which motivate travellers to post online reviews (Bakshi, Dogra and Gupta 2019).

Regarding the use of the hotel websites as a forum for posting client opinions and the online reputation score, there are some papers that have suggested that hotel establishments have not exploited the full potential of their websites as a tool for the management of opinion and reputation (Li, Wang and Yu 2015;De Pelsmacker, Van Tilburg and Holthof 2018). They have instead focused their efforts on providing information that reflects the features of their hotels. Nevertheless, in accordance withDe Pelsmacker, Van Tilburg and Holthof (2018), the ratings shown on the website could affect room occupancy and productivity. However, despite the potential benefits for hotels of displaying their online reputation on their websites and the fact that a high percentage of customers would not book accommodation without first reading the opinions of other users, to the best of our knowledge, there are no studies that rate how hotel establishments are using their official websites to reflect the opinions of their clients, by posting both internal and external ratings, as well as the variables that could be related to the characteristics of online reputation.

Our study is focused on hotels in Andalusia (Spain), a hotel sector like so many others that is having to adapt to technological change and the new procedures for planning trips and selecting tourist destinations. Especially, if we recall that 1,699 Andalusian hotels accommodated 18.3 million tourists in 2017, of whom 8.9 million were foreigners, ranking Andalusia as the second most visited region in Spain and contributing to Spain’s position as the second most visited country in the world by tourists and the most competitive economy in the world in terms of tourism (Calderwood, Soshkin and Fisher 2019).

Considering the range of all hotels, we have focused this paper on 4- and 5-star hotels in Andalusia, which represent over 30% of the Andalusian hotel establishments and offer almost 70% of total hotel capacity. The variables that could be related to the characteristics of online reputation are described below.

1.1. The number of hotel stars

Currently, star ratings remain a crucial consideration for tourists searching for hotel accommodation, while online reviews provide further information related to quality standards (Mohsin, Rodrigues and Brochado 2019). Moreover, hotels with higher star ratings are much more sensitive to online customer ratings than hotels with fewer stars, especially with regard to the cost of their rooms (Öǧüt and Taş 2012). Thus, with reference to the variables that may have an effect on online reputation, hotel establishments with more stars present better reputation ratings, verifying this system of classification (Martín-Fuentes 2016). Nevertheless, 5-star hotels, which specialize in luxury and exclusivity, may be less likely to display an online rating on their official website. Were they to display a rating, they may not choose to display it on the home page, which those types of establishments might consider inappropriate.

Regarding the inclusion of online reputation on hotel websites, in accordance withDe Pelsmacker, Van Tilburg and Holthof (2018), the ratings shown on the website will have: (1) a negative indirect effect for hotels with fewer stars and no significance for hotels with higher star ratings; (2) a direct effect on room occupancy and a positive effect on productivity.

H1a: The number of hotel stars will influence the publicity that is given to online reputation.

H1b: The number of hotel stars will influence the (numeric or non-numeric) type of rating of online reputation.

H1c: The number of hotel stars will influence the use of external ratings of online reputation.

1.2. Hotel modality

According to the findings ofTran, Ly and Le (2019), online ratings appear to reflect customer choice over the whole range of hotel modalities. Thus, a hotel that increases its online ratings will improve positive responses from its customers. So, the modality of a hotel (motorway, rural, urban and beach), unlike other features of the establishment, is initially not a deciding factor with regard to the policies on the publicity that is given to online reputation on hotel websites. Nevertheless, a possible relationship between Andalusian hotel modality and publicity, type and external rating were analysed.

H2a: Hotel modality will influence the publicity that is given to online reputation.

H2b: Hotel modality will influence the (numeric or non-numeric) type of rating of online reputation.

H2c: Hotel modality will influence the use of external sources of online reputation.

1.3. Hotel age

Several studies have analysed the degree of influence of hotel age on business performance (Othman and Rosli 2011;Marco 2012;Xie, Zhang and Zhang 2014). Their findings indicated that hotel age was not an important attribute for hotel performance.

Salavati and Hashim (2015) found no significant association between hotel age and the number of website updates or the performance of the hotel website. Nevertheless, the establishments launched after the booster effect of online reputation scores, since they began their activity within that environment, will probably have incorporated the management of online ratings, from the outset, in a more straightforward manner. Besides, older hotels, it appeared, preferred to outsource the rating management.

H3a: Hotel age will influence the publicity that is given to online reputation.

H3b: Hotel age will influence the (numeric or non-numeric) type of rating of online reputation.

H3c: Hotel age will influence the use of external sources of online reputation.

1.4. Hotel size

Another variable that may have an impact on online reputation could be hotel size. However, although hotels with many rooms will usually have a higher number of reviews, the rating that is achieved is, it would seem, unrelated to the size of the establishment (Martín-Fuentes 2016). In contrast, hotel size is not likely to have a significant impact on business performance (Xie, Zhang and Zhang 2014). Moreover, the size of the organization is not a determining factor in the use of Information Technology (Seyal, Rahim and Rahman 2000).

Nevertheless, assuming that additional economic resources will improve online reputation management, we posit that smaller hotels, normally family-owned hotels or hotels with fewer resources, may find it more difficult than hotel chains to keep their website updated with the comments and the evaluations of clients. Furthermore, it may be more difficult for them to manage the opinions internally, preferring, in their case, to outsource this management or to publish the ratings that they have obtained with hotel comparison websites or on world renowned booking websites (for example, TripAdvisor or Booking).

H4a: Hotel size will influence the publicity that is given to online reputation.

H4b: Hotel size will influence the (numeric or non-numeric) type of rating of online reputation.

H4c: Hotel size will influence the use of external sources of online reputation.

1.5. Affiliation to a hotel chain

According toDe Pelsmacker, Van Tilburg and Holthof (2018), the ratings shown on the website have a moderate effect on both hotel chains and independent hotels. In contrast,Cascales, Fuentes and Esteban (2017) reported that the hotels in their study that were affiliated to a hotel chain attached greater importance to online reputation, via review sites and official websites. Indeed, any manipulative practices on their part relating to reviews tended to be lower (Mayzlin, Dover and Chevalier 2014).

We raise the question here of whether the publicity given to online reputation falls within their corporate policies. Moreover, the resources available to chain-affiliated hotels will be greater than other types of hotels, in order to increase room occupancy and to promote the hotel (Tarí et al. 2009). Consequently, hotels that form part of a hotel chain are likely to have more support than other hotels to display their online reputation rating on their own websites. Moreover, those establishments usually use a website template unified by their hotel chain. They almost all, without exception, have centralized reservation mechanisms and procedures for placing and for gathering reputation indicators that could be determining factors in the type of rating that they display.

H5a: Affiliation to a hotel chain will influence the publicity given to online reputation.

H5b: Affiliation to a hotel chain will influence the (numeric or non-numeric) type of rating of online reputation.

H5c: Affiliation to a hotel chain will influence the use of external sources of online ratings.

2. METHODOLOGY

We worked with data from 2017 on 522 active 4- and 5-star hotels in Andalusia (Andalusian Regional Department of Tourism and Sports 2017). Having verified, in January 2018, whether the hotels had their own website, only 503 provided sufficient data for analysis.

We analysed two different variables for each hotel: (1) those that define the general profile of the establishment (number of the stars, modality of hotel, age, size and affiliation to a hotel chain); and, (2) those that refer to online reputation (publicity, type and source of the online-reputation rating). In total, 9 categorized variables were analysed.

Regarding hotel modality, based on the modalities formed by the hotels on the Tourism Register of Andalusia (Andalusian Regional Department of Tourism and Sports 2017), three categories were distinguished: motorway hotels and rural hotels; urban hotels; and beach hotels. The Tourism Register of Andalusia classifies the hotels into four modalities, actually, but, given the scarce few road hotels (only 6 establishments of this modality were registered), they were grouped under the rural category, in order to obtain statistically representative results.

We also established criteria to define the age of the establishments: a hotel had to have commenced activity either before or after 2010, the year in which the hotel sector enhanced its use of online reputation as a source of strategic information. Indeed, 2008 and 2009 were the two years in which some companies dedicated to the management of online reputation commenced their activities, such as Customer Alliance, ReviewPro, and TrustYou.

The variable related to the size of the hotel was divided, according to the number of rooms, into three categories (small, medium, and large). In that respect, we considered that small hotels had fewer than 50 accommodation units, medium hotels had between 50 and 300, and large hotels had over 300 rooms that were available.

Furthermore, with regard to the type of online reputation rating, we differentiated between the hotels that displayed a numeric rating or did not, showing only a non-numeric indicator of its reputation, regardless of whether it was a symbol (stars, circles, etc.) or a list of client appraisals with no exact score.

Finally, it was considered that establishments tended to opt for external sources of online rating when offered an online reputation ratio either from a review aggregator (Customer Alliance, ReviewPro or TrustYou) or another similar source (comparison and booking websites). Specifically, four categories were defined for the type of external online rating: (a) a review aggregator; (b) a single external source that is not a review aggregator; (c) several external sources, without including review aggregators; (d) a review aggregator plus another external source.

After a descriptive analysis based on the frequencies of the variables, possible dependent relationships were analysed with the hypothesis test through the chi-square statistic, using SPSS software version 2.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, N.Y., USA). Specifically, five multiple hypotheses were initially posited, which attempted to analyse whether the variables (number of stars, modality of hotel, age, size and affiliation to a hotel chain) might influence the publicity given to the online reputation on the hotel website, the type of rating provided and the posting of external sources of online reputation on the hotel website.

3. FINDINGS

3.1. Descriptive analysis

The results obtained after analysing the variables are shown inTable 1. Most of the hotels were 4-star establishments (90.26%), were located in the city (48.11%) or on the beach (40.95%), had begun their activity prior to 2010 (87.08%), were considered to be medium sized (62.03%), and were affiliated to a hotel chain (68.99%).

Regarding online reputation, it should be noted that only 53.08% of the 4- and 5-star hotels had some indicator of their rating on their own website. While in the 5-star category the percentage was slightly lower (45%). When online reputation was shown, it was usually displayed on the home page (86.89%) and, at least, with one numerical score (76.4%). Interestingly, 34 of the 267 hotels that showed some form of online reputation indicator on their website chose not to display a single figure, although they complemented their numeric ratings with symbols and provided several internal and external sources, thereby adding valuable information to their website.

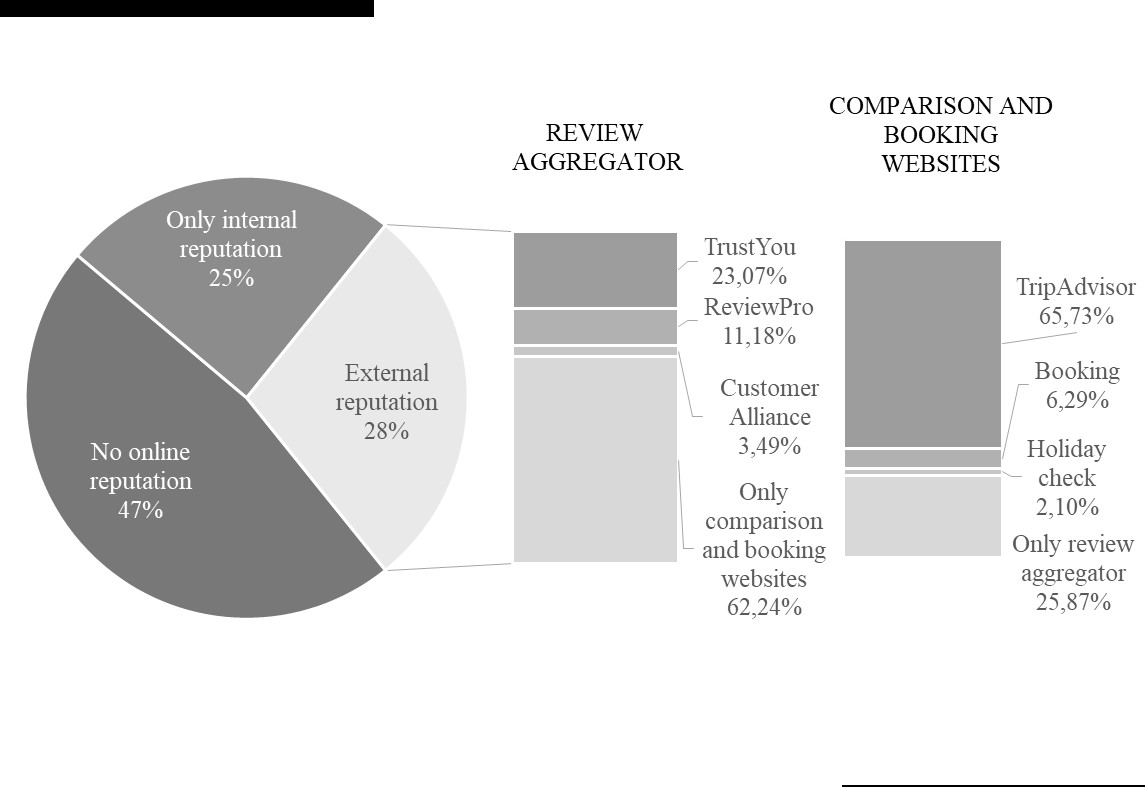

A higher percentage of the hotels under analysis used external online reputation scores (53.56%) although, in some cases, complemented with customer opinions. A deeper analysis of the external online ratings offered on the web showed that the majority (53.85%) of the 143 establishments with this type of online reputation chose to offer a single external source, specifically: TripAdvisor, Booking, and Holiday check. If we group the cases in which the hotel's website offers several sources of online reputation, the importance of the source of the online rating increases. Thus, as can be seen inTable 2, where external web sources and the opinion aggregator were not exclusive, hotels were to a greater extent opting for TripAdvisor and TrustYou as guarantors of online reputation.

If we consider the total number of hotels, the importance of TripAdvisor as an indicator of online reputation can be clearly seen. On that point, it should also be highlighted that 35.21% of the establishments that displayed online reputation scores on their website and 65.73% that used external sources showed their TripAdvisor rating (Figure 1), whether exclusively or in addition to other reputation evaluations, which is a reference point between the hotels under analysis.

3.2. Hypotheses TestingThe hypotheses were tested by means of the chi-square statistic, obtaining the results shown inTable 3. Some hypotheses could not be tested, due to the fact that they did not meet the necessary requirements to apply the chi-square statistic, as some estimates had an expected count of less than 5 (Table 3).

In accordance with the results of the hypothesis test (Table 3), the number of stars neither affected publicity (H1a), nor the type of rating displayed (H1b), nor the decision to use external sources of online reputation ratings (H1c).

According to the chi-square statistic, H2a and H2c were confirmed. A significant relationship exists between hotel modality and the publicity given to online reputation (χ2 = 12.914, p =0.002, p< 0.05), as well as the use of external sources to display a reputation-related rating on the website (χ2 =12.242, p =0.002, p< 0.05). Accordingly, the urban hotels were the most inclined to display their online reputation on their websites (60% of the establishments in this modality). Otherwise, the beach hotels tended, to a larger extent, to opt for publishing an external rating of their online reputation (67% of beach hotels that offered their online reputation).

On the other hand, the fact that the hotel had started its activity after 2010 was, according to the hypothesis test, not dependent on the decision to show the online reputation on the establishment’s official website (H3a), the type of rating (H3b), and the use of external sources of online reputation (H3c).

Regarding hotel size, the results of the hypothesis test confirmed H4a and H4c. In that sense, Table 3 shows a statistically significant result relating the size of the hotels with the publicity of online reputation (χ2 = 25.14, p =0.000, p< 0.05) and with the decision to show their reputation ratings obtained through external sources (χ2 = 11.88, p =0.003, p< 0.05). In that regard, online reputation via hotel website was less frequent among smaller hotels (34% of total small hotels, compared with 58% achieved by the larger hotels). In their case, the use of external sources of online reputation was not usually a chosen option (only 36% of the small hotels that displayed an indicator of their online reputation did so using an external rating), because they preferred to post client opinions directly on their website.

Finally, according to the results of the hypothesis tests, affiliation to a hotel chain influenced the decision of a hotel to publicize its online reputation rating on its own website (χ2 = 65.487, p =0.000, p< 0.05), so H5a was confirmed. In all, 65% of the hotels affiliated to a hotel chain displayed their online reputation on the website compared with 26% of the independent hotels.

A summary of the results obtained in the hypothesis testing is shown inTable 4.

CONCLUSION

There are ever-increasing numbers of tourists who consult the Internet both for planning and for searching for information, as the online reputation of the possible destination is one among various decision-making criteria. Considering, in addition, the development and the extension of the use of OTAs as a reservation procedure for accommodation, it is essential for the hotels to have an appealing website, in order to be able to compete through direct reservations. In that regard, the use of hotel websites as a marketing strategy in some countries was studied, by analysing what information was shown, arriving at the conclusion that they were used ineffectively (Li, Wang and Yu 2015;De Pelsmacker, Van Tilburg and Holthof 2018). Although they analysed whether or not the websites showed client opinions or links to review pages like TripAdvisor (De Pelsmacker, Van Tilburg and Holthof 2018), they remained silent over the online reputation indicators and the type of rating that was shown, as well as any possible variables that may be of influence.

The results of our study have demonstrated two important aspects. First of all, that Andalusian 4- and 5-star hotels are adapting to the new competitive environment of online sales, in which the opinions of previous clients may be a determining factor in the selection of the hotel establishment. This tendency can be seen from the information relating to online reputation that 53.08% of the hotels displayed on their websites.

Secondly, with regards to type and source of the rating, the establishments that were analysed tended, in their majority, to display a numeric score on the home page and, in 53.56% of all cases, used an external source of online ratings, mainly with the result displayed by a review aggregator or the rating obtained by the hotel on TripAdvisor.

The typical profile of a hotel that displayed an online reputation indicator on its website was either a medium or large-size urban hotel affiliated to a hotel chain.

In accordance with the results of the hypothesis test, a significant relationship exists between hotel modality and the publicity given to online reputation (H2a), as well as the use of external sources (H2c). Furthermore, a statistically significant result was found relating the size of the hotel with both the publicity given to online reputation (H4a) and the decision of the hotel to show its reputation ratings obtained through external sources (H4c). Finally, it became evident that there was a relation between the affiliation to a hotel chain and the decision of a hotel to publicize its online reputation rating on its official website (H5a).

On the other hand, the number of stars did not affect publicity (H1a), type of rating (H1b) or decision to use external sources of online reputation ratings (H1c). In addition, the age of the hotel was not dependent on the decision to publicity the online reputation (H3a), the type of rating (H3b) or the use of external sources (H3c). Regarding hotel size, the results of the hypothesis test showed no significant result in relation to the type of rating (H4b). Likewise, the relationship between affiliation to a hotel chain and type of rating (H5b) or use of external sources of online reputation ratings (H5c) could not be demonstrated.

The main contribution of this work is that it has shed light on how hotels treat online reputation publicity on their official websites, at a time of high competition from OTAs. According toDe Pelsmacker, Van Tilburg and Holthof (2018, p. 53) "integrating third party reviews on the hotel website seems to be most important, since they have an impact on both the number and the valence of online reviews, which in turn leads to both a higher room occupancy and RevPar". Surprisingly, we found that 46.92% of hotels displayed no information on their online reputation, which reduced their chances of directly marketing their rooms, allowing other reservation websites to do so instead. In that respect, 35.21% of the hotels accepted TripAdvisor as the main point of reference for the selection of tourist destinations, which were similar to the results obtained (37.98%) in the study which sampled 3- and 4-star hotels in Belgium, in 2016 (De Pelsmacker, Van Tilburg and Holthof 2018). This external management rating system could be especially interesting for those hotels without sufficient economic resources to manage online opinions internally or unable to afford a review aggregator. While until just a few years ago TripAdvisor acted solely as a comparison site for the hotel industry, since 2016 it has offered the possibility of making reservations via the TripAdvisor website, converting it into a direct competitor to the hotel websites. Bearing in mind that hotel establishments are currently seeking to promote direct sales as a growth strategy via a reduction in commission for OTAs, the conversion of TripAdvisor into an instant booking enabler could change the attitude of hotels with regards to the use of the TripAdvisor brand for online reputation.

In addition, this work allows to put the focus on smaller establishments that do not belong to hotel chains. It is this type of hotel that hotel associations and government bodies should focus on in order to improve their competitiveness through the improvement of websites and the promotion of direct bookings.

We are conscious of the fact that the conclusions of this study cannot be generalized, due to its investigative focus on 4- and 5-star hotels in Andalusia, characterized by a high rate of association with hotel chains. Those chains may in turn have a knock-on effect on the publicity of online reputation, as it is incorporated, in many cases, in corporate policies. It would, therefore, be interesting to widen the field of the study to all hotels with fewer stars, in order to analyse whether they behave in a similar way to the hotels of a superior category. Future investigations will therefore analyse its presence in the above-mentioned establishments, as well as widening the geographical field, in order to analyse any possible parallels in a search for more general conclusions.