1. INTRODUCTION

The proliferation of emerging destinations has led to more countries competing for potential tourist markets, therefore managing destination competitiveness became a prominent factor in the global tourism industry. Nevertheless, it is equally important to examine the socio-economic prosperity of a competitive destination as this signifies changes in wealth, education, the local environment and citizens’ welfare as a destination develops. In turns, this may affect changes in income and distribution of wealth, hence affecting the overall Quality of Life (QOL). This paper discusses whether increasing tourism competitiveness translates into increasing social welfare for host communities, and then, to test this notion, investigates how destination competitiveness has affected residents’ livelihoods in Bali.

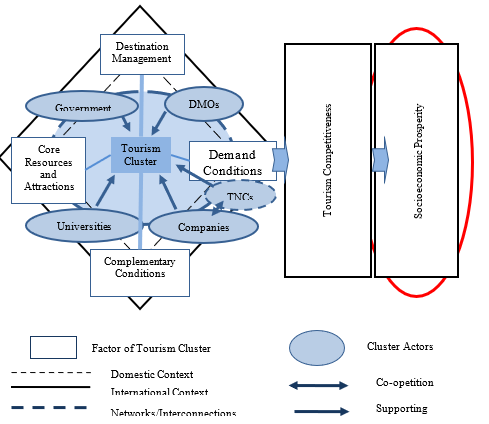

Research has assessed tourism’s impacts on residents’ QOL (Andereck and Nyaupane 2011;Kim et al. 2013); links between societal prosperity and tourism (Dwyer and Kim 2003); residents’ attitudes towards tourism (Kayat 2002) and the importance of destination competitiveness (Armenski et al. 2017), however, research has not examined measuring socio-economic effects using the key insights fromKim and Wicks’ (2010) Tourism Cluster Development Model. While the current literature has focused on measuring destination competitiveness and examining the appropriate competitive factors, there is little empirical evidence taking into account cluster actors such as Transnational corporations (TNCs) and Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) (as seen inFigure 1) which are highly relevant for developing destinations in the assessment of destination competitiveness. The phenomenon of competitiveness is claimed to be versatile, revealing a number of dissimilar options in terms of strategy and management perspective, historical and socio cultural perspective as well as a price competitiveness perspective. Different standpoints illustrate a diverse range of different understandings, definition and measurement of competitiveness.

Crouch and Ritchie (1999) give an in-depth observation about the tourism competitiveness model associated with a wider literature such as in the context of national economies and concentrated on the long term economic wealth as a guideline for sustainable growth.Dwyer and Kim (2003) took causal relationships into consideration. They expanded the literature of destination competitiveness to facilitate easier comparison between industries across nations with the objective to distinguish key success factors contributing towards competitiveness of a nation and recognising the potential and limitations of a destination. AlthoughCrouch and Ritchie (1999) andDwyer and Kim (2003) mentioned socio-economic prosperity of a destination briefly, no further research has investigated whether destination competitiveness generates increased welfare for its host population as assumed in their models.

Our paper is the first attempt to investigate the link between destination competitiveness and host community QOL based on the perceptions of key stakeholders. Our paper aims to close this research gap and investigates the social welfare impacts on Bali’s residents resulting from destination competitiveness and gives insights for tourism practitioners and policy-makers. The inclusion of social welfare implications for residents within the planning and management of tourism is highly significant, as quality tourism experiences are closely associated with receptive host communities (Andereck and Vogt 2000).

The paper is structured in four parts. Kim and Wicks’ Tourism Cluster Development Model is briefly outlined before the research methodology is presented. The paper’s main section analyses the key themes that emerged during fieldwork interviews in Bali. Finally, the paper concludes that socio-economic prosperity is not guaranteed although a destination appears successful. Our findings show that economic prosperity achieved through tourism competitiveness in Bali does not always translate to increased social welfare, nor reduce spatial nor power inequalities.

2. KIM AND WICKS TOURISM CLUSTER DEVELOPMENT MODEL

Competitiveness models specifically developed for tourism are essential to understand the product of tourism as it is atypical from any other manufactured products. Previous literatures have looked at different aspects of competitiveness from the relationship between price and tourism competitiveness (Dwyer, Forsyth and Rao 2000;Go and Govers 1999); environmental features related to identifying key characteristics of market competitiveness (Hassan 2000) and ways develop an integrative conceptual framework of destinations (Pearce 2014). Competitiveness at national level symbolises an upgrade in the standard of living, creation of future job opportunities, as well as increased real income for its respective people, hence looking into the social welfare implications of a destination is vital.

Kim and Wicks’ (2010) Tourism Cluster Development Model (Figure 1) is a reformulated and combined version of Porter’s Diamond model with the Tourism Competitiveness model ofCrouch and Ritchie (1999) andDwyer and Kim (2003). Kim and Wicks’ conceptual framework indicated the significance of collaboration between cluster actors; and the difference in roles and responsibilities between Porter’s four conditions, all act as useful attributes showing key potentials and limitations of a destination. The importance of clusters and how each cluster actor works towards networking and interconnection is also emphasised. The notion of cluster theory is popular in creating competitive advantage to aid tourism planners or policy makers achieve sustainable development. An awareness of this theory will improve a vital aspect or features of networks which are more likely to bring success to any industry. “Porter’s theory of competitiveness of nations and the concept of cluster has been considered one of the most successful and influential theories or models which help identify the factors which can achieve optimal competitiveness in national and regional development” (Kim and Wick 2010, 2). Cluster actors such as the TNCs, FDI, Universities, and the concept of co-opetition has been included in this model, which reflects more accurately in rapidly developing economies.

The study ofChin et al. (2015) applied Kim and Wicks Model to Bali, illustrating the linkage between cluster actors, and how such factors could affect the competitiveness of this small destination. The study was set out to explore the determinants and attributes from Kim and Wicks and their findings concur with Kim and Wicks’ conceptual framework indicating the significance of collaboration between cluster actors; and the difference in roles and responsibilities between Porter’s four conditions, all act as useful attributes showing key potentials and limitations of Bali. There is however partial agreement with some aspect of the theoretical framework such as the theory of co-opetition. Their study showed that co-opetition only exists between TNCs and medium-sized companies and the relationship of competition and cooperation between TNCs and small domestic businesses does not seem to exist. Results also showed limited interaction between universities and other cluster actors due to constant conflict of objectives and dissonance. Furthermore, although the significant role of TNCs in developing economies were recognised,Chin et al. (2015) challenges the notion that competition was the main factor that stimulates new business formation or supports innovation due to the fact that local Balinese businesses appear to have fewer chances in competing directly with TNCs. Their study highlighted detailed analysis of the destination’s strengths and weaknesses,

and provide a nuanced understanding of how cluster actors have worked to facilitate a competitive tourism destination like Bali (SeeChin et al. 2015 for further details). With Bali proven as a competitive destination, this paper will in turn add value to how such competitiveness has contributed or affected the lifestyle of the host communities. This present paper will continue to explore whether economic prosperity achieved through destination competitiveness, as claimed in Kim and Wicks model, actually translates into social welfare, particularly in a mature destination such as Bali (SeeFigure 1). This paper will discuss whether increasing tourism competitiveness cascades down contributing to a destination’s socio-economic prosperity and investigate how it has affected residents’ livelihoods in Bali.

2.1. Quality of Life (QOL)

In order to investigate the socioeconomic issue related to destination competitiveness, a brief literature on socioeconomic prosperity is therefore illustrated. Socio economic policy is normally involved with the amalgamation of economic and social concerns which results in socioeconomic development which enhances the Gross Domestic Product (GDP), literacy rate, employment levels, education and leisure time which will determine the quality of life (QOL) and the wellbeing of the individual and the general public (Gregory, Johnston and Pratt 2009). Nevertheless, according to Costanza (2008), QOL is a highly subjective matter, as one country’s indicators of happiness might not be similar or acceptable in another country. Hence, the measurement of socio economic prosperity might be based on Subjective Wellbeing[1] (SWB) as the clarity of the whole concept has been indefinable. There are a variety of methods used to measure national QOL and human advancement. Approaches that measures QOL of citizens can be objective as well as subjective. As most governments choose to use objective methods in measuring QOL of citizens, objective approaches became widely accepted. General technique employed to analyse the QOL objectively includes indicators such as GDP per capita, health, literacy rate, mortality rate, education, life expectancy and many more (Becker, Philipson and Soares 2003). These indicators demonstrate how competently the government has achieved their targeted GDP or literacy rate for instance, in comparison with other countries. However, this does not necessarily result in better QOL or improved living conditions. For example, an increase in GDP growth rate does not necessarily mean higher QOL. Additionally, even if there is higher QOL, in terms of higher GDP per capita and literacy, higher QOL does not always equal higher life satisfaction. The GDP value only measures the average wealth of the nation, but does not measure whether this wealth is evenly distributed between its citizens. Government, NGOs such as United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and United Nations World Tourism Organisations (UNWTO); all used objective techniques to collect significant data. Nonetheless, this approach can only measure indicators at aggregate level using the country as the unit of analysis (Shackman, Liu and Wang 2005).

Nevertheless, to get a more holistic picture in measuring the QOL of a society,Diener and Suh (1997), argued that SWB are imperative indicators that should be included to fully comprehend and assess the accurate perceptions of society. According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), QOL is defined as “individuals’ perceptions of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards and concerns” (World Health Organisation, 2019, pp. 1). In other words, QOL is seen from a subjective standpoint. Researchers such asCamfield (2004);Veenhoven (2007) andMcGillivray (2007) offered alternative ways for measuring non-economic aspects of QOL through subjective approaches. This involves taking into consideration people’s responses and reactions to their lives and the society that they live in. Citizen’s perceptions and voice, qualities of environment as well as self-perceived satisfaction needs to be considered. (See Methodology for detail methods chosen)

3. METHODOLOGY

The Indonesian province of Bali was selected to test Kim and Wicks’ framework as the island is one of the most successful small developing economies regarding tourism’s contribution to GDP within South-East Asia (OECD 2019). Bali was chosen for fieldwork due to its significant tourism development which has made Indonesia’s main tourism hub. In July 2019, Bali was recorded to have 3.5 million international tourist arrivals (Bali this week 2019). Additionally, the drastic changes to Bali’s tourism development and the evident rapid uncontrolled development are all characteristics of Bali which can be examined to ascertain whether the economic benefits associated with destination competitiveness translates to increased social welfare for the host community.

Fieldwork took place over four weeks using a rapid rural appraisal approach with qualitative data collection techniques (Ellis and Sheridan 2014). The paper’s authors have extensive prior experience of tourism in South-East Asia and a long connection to Bali, whatPagdin (1989) calls ‘pre-knowledge’ of the field work location. A rapid appraisal (RRA) type approach was considered to be the most appropriate applying the authors ‘pre-knowledge’ to maximize data collection due to budget and logistical constraints.The RRA is an inexpensive and reliable method for identifying stakeholder groups in Bali by using techniques relying on expert observation coupled with semi-structured interviewing local leaders, community and officials. This method is gaining recognition and is being used in the identification of community problems, and for monitoring and evaluation of ongoing activities. This approach is useful in this research to gather information on a broad range of community perceptions; to develop a better understanding of the actual situation of community life in Bali; and to appreciate the interlinked factors within the framework. In terms of positionality, the authors intensively discussed the context of the project at the pre-fieldwork stage and during the creation of the interview protocols. During the field work itself, as well as undertaking the main task of interviews, direct observations and other notes were detailed in reflective field journals, and then post-visit, comments and interview data were interrogated in light of emerging themes and possible contradictions. This echoes the importance of self-reflection in qualitative field work both before, during, and afterwards in the production of ‘stories’, in this case, this particular research article.

Legian, Denpasar, Sanur, Kuta and Ubud were selected locations for the interviews due to the rapid pace of tourism development there. Interviews were also undertaken in Kintamani, a small village in North Bali. Interviewing respondents in regions experiencing a fast pace of tourism development as well as in regions with limited development provided valuable information and differing opinions on how locals felt tourism had affected their lives. N=28 in-depth, semi-structured interviews were conducted during peak tourist season (June) with average interview length of approximately 1.5 hours (See Appendix:Table 1 for respondents lists andTable 2 for the typology of stakeholders). Few interviews were carried out via skype due to vast locational difference. Semi-structured interviews were carried out and interviewees (local residents) selected based on their accessibility and proximity to the researcher. Respondents such as beach vendors, taxi drivers and local small business owners were interviewed using convenience sampling as they were easily available in the busy tourist areas. Furthermore, key stakeholders in the tourism industry including government officials, tourism boards, travel agencies, tour operators, universities, and NGOs were also interviewed.

3.1. Parameters

A reliable set of parameters and indicators for socio-economic issues need to be acknowledged to construct appropriate interview questions. Secondary data formed the parameters and indicators for measuring the host residents’ social welfare. Numerous techniques exist available to measure QOL (Andereck and Nyaupane 2011;Diener and Suh 1997), however, only the most relevant parameters were chosen, specifically, to create interview questions concerning locals’ perceptions of socio-economic prosperity and used the ‘Happy Planet Index’ and ‘Gross National Happiness’. The aim was not to calculate these indices value per se, but to utilize them to compose appropriate questions for primary data collection. By using subjective well-being to confine the intricacy situation of ‘happiness in a society’, the indicators incorporated into the Happy Planet Index and Gross National Happiness informed question design for measuring citizens’ social welfare.

Happy Planet index takes into account the wellbeing of society but also the issue of sustainability. It measures happiness and opportunities of individuals and concerns the efficiency of each country’s utilisation of the planet’s natural resources. The opportunity and benefit of happy and healthy lives of the current generation should not be made at the cost of future generations (NEF 2013). Moreover, the Happy Planet index argued that an increase in consumption of planet’s resources does not necessarily indicate an increase in its wellbeing. By using subjective wellbeing to define ‘happiness in a society’, indicators incorporated in the Happy Planet Index include individual vitality such as the strength to overcome difficulties in life; opportunities to undertake meaningful, engaging activities which confer feelings of competence and independence; life satisfaction; a sense of belonging to the society and the feeling of relatedness (NEF 2013).

Similarly, Gross National Happiness (GNH) takes into account both objective and subjective perspective to achieve equilibrium, reflecting values and giving advice on the successful policies and programmes. For instance, the perceptions on the safety of the society are almost as significant as the objective value of crime rate in order to achieve peace of mind, hence happiness. GNH is created to incorporate the social and environmental variables to design an indicator that measures quality of life more accurately and comprehensively (GPI Atlantic 2005). The Gross National Happiness indicators are ‘Time use’ such as value of non-work time for happiness like personal care, community participation, religious activities; ‘Community vitality’ in terms of family indicator, social support; ‘Culture diversity and resilience’ such as maintenance of cultural traditions like Dialect indicator, community festivals; and ‘Living standard’ like income indicator. With the help of existing literature and projects in establishing the parameters and indicators for socio-economic aspects, indicators can be carefully selected from the commonly used ‘parameters’. Although some are not directly extracted from the field of tourism, these can assist in identifying significant and pertinent factors to measure socio-economic prosperity. Those indicators as seen inFigure 2 were chosen as they convey important meanings to measure the residents’ QOL which are more detailed than general indicators such as GDP, literacy, crime or mortality rates. More importantly, those indicators could be incorporated into the tourism context to identify how competitiveness has affected the way locals live. (See Appendix for full interview questions andTable 3 for cross reference of interview questions and parameters/framework). All interviews were fully transcribed, then coded and analysed using Nvivo software to identify key themes. The researchers identify the key themes based on the interviewees transcription by characterising particular perceptions of key stakeholders and experiences that the researcher sees as relevant to the research question. (See Appendix:Table 4)

4. RESULTS AND ANALYSIS

Concerning Bali’s dependence on tourism, respondents from Ubud, Kuta and Legian felt very strongly about the reliance on tourism, as most expressed that they need to maximise their earnings within the ‘fruitful season’ and explore other opportunities during off-peak season. Respondents were aware that they were in a disadvantageous position but felt powerless to react or do anything to solve it. The majority of the respondents who were employed directly in tourism - for instance, hoteliers, taxi drivers, tour operators, and vendors concerns about the over-dependence on revenue from tourism: “Without tourists I can’t live. I have been driving around tourists for years and my earning is based only on my basic salary and their generous tips. If they don’t come, I can’t bring any money back to my wife.”

Respondents also expressed apprehensions about their livelihood and their burden providing for families if tourists no longer see Bali as an attractive destination. These concerns are understandable given the terrorist bombings of 2002 and 2005 (Putra and Hitchcock 2009). Respondents noted the devastating effects for Balinese and their businesses after the bombings. Most locals especially in tourist towns were so dependent on tourism that their livelihood was threatened, and their spending on basic needs such as food, clothing and education for children were reduced. Besides economic problems, social problems also increased such as alcohol abuse and the crime rate. Travel agencies and tourism related businesses made significant redundancies, shops and restaurants closed and beach vendors lost work. “The bombing happened when I had just started my business which was a very hard time for me to keep it going.”

AsBaker and Coulter (2007) observed, locals normally work at the bottom of the hierarchy resulting in a high reliance on tourism. Our findings reinforce those of Baker and Coulter on the over-dependence on tourism on local livelihoods. This can be seen by the decrease in income due to the falling tourist numbers. After the 2002 bombing, international visitor’s numbers were 38% lower in June 2003 than at June the previous year (Bali Tourism Authority 2004). There was no safety net for locals and people were not in the position to either ask for contingency plans from authorities, or know how to plan themselves. Bali risks concentrating too much on a single sector of the economy (Feenstra and Hanson 1996).

Villagers from Kintamani were dissatisfied with the unequal benefits within Bali. They stated that people living in Southern Bali like Kuta, Sanur or Legian area benefited more from tourism than people living in Kintamani: “We only get the occasional tourists brought by some drivers who have some association with me . . . Well I would be happier if there is more equity and fairness. If my land is situated in town, I would have been richer by having my land rented out or having a partnership business with investors.” The findings show the perception of the unequal distribution of income, employment and benefits. With an influx of tourists and investors to Bali, it is inevitable that their presence would impact on the local communities. However, it is useful to examine how much it has affected communities.

Our findings show partial agreement with Kim and Wicks model as the locals’ QOL has improved to a certain extent as evidenced by low poverty levels in Bali. Nonetheless, income inequality still continues, and also spatial inequalities between urban dwellers and rural villagers. The socio economic prosperity as claimed in the framework was not found to be equal in all areas of Bali. The positive knock on effect of tourism did not seem to reach all levels of locals, leading to inequality of wealth and opportunity.

4.2. Power Issues

The majority of the respondents who expressed negative perceptions over power issues were academics and DMOs, as most of them felt that there was an unequal power distribution in the tourism industry. Since tourism involves an array of stakeholders, respondents felt that they were the least powerful group while they perceived the rich and those within the government sector as the most powerful. This inequality of power is not new to the Balinese and in recent times, arguably this has been obvious since at least the 1980s as exemplified the administration of Bali’s former Governor, Ida Bagus (1988-1998) who was known for favouring foreign investors as well as the interest of the Jakarta conglomerates. He was seen to give foreigners priority for business opportunities although Jakarta companies could arguably not be considered ‘foreign’ (Hitchcock 2000). This has led to dissatisfaction in the local community for years and the situation has not improved since then:

“Foreigners and businessman from other parts of the Indonesia come to Bali with the main aim of pushing our prices down at the cottage industry and our plantations. They demand a huge discount and buy in bulk from us. They then sell it at a higher price to earn a huge amount of profit. We do not have connections or capital to set up a business line, that is why we are being taken advantage of by those businessmen.”

Respondents also mentioned the case of building the resort near Tanah Lot in 1994, where local opposition was made clear to the authorities. The locals felt that the authorities have disregarded their opinions and several respondents mentioned the controversy over the building of the Pan Pacific Nirwana Bali resort within two kilometres of Tanah Lot, a very sacred temple. They expressed strong disagreement with the project and were unhappy that the government approved it regardless of local opposition. The situation was exacerbated when local family temples were displaced and relocated to places away from the construction of the resort: “Locals were furious and there was a huge influence on their cultural traditions. We feel that we were treated unfairly and this has definitely affected our opinion on tourism.”

Additionally, the unequal distribution of power however does not only apply between government and communities but also within government and non-governmental organisations. Theoretically, popular organisations like environmental groups should take part in the decision-making process for responsible tourism. This was however not the case in the 200-hectare resort project built to host the 2013 Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) forum in Jimbaran (Reuters 2011). Although environmental groups expressed concerns over the degradation of coral and air quality but were effectively ignored and the provincial government approved the project. The issue is made even more complex with the difference of power wielded between the central and provincial government. This can be seen in several other cases elsewhere in Indonesia where the different power relationships between tourism developers and operators have affected the development of tourism on the island of Lombok, Indonesia (Hampton and Jeyacheya 2015).

The notion that socio economic prosperity can be achieved in Kim and Wicks framework when a destination is competitive, does not fully concur with our findings. This study demonstrated the dissatisfaction of local communities concerning unequal power distribution not only between government and communities but also inter- government such as central and provincial as well as between non-governmental organisations. The assumption that socio economic prosperity will be achieved can be seen as generalisation in the model, since tourism involve an array of different stakeholders at different levels. Categorisation of these stakeholders will provide a clearer view on how tourism competitiveness has affected communities’ quality of life in Bali. Our results show the distribution of power tilted towards the authorities, rather than Bali residents.

4.3. Corruption

This issue drew the strongest reactions from most respondents. Most recognised that corruption is a major issue not only in Indonesia but in many developing countries.Campos (2001) commented that Indonesia had been ranked among the most corrupt countries in the world andMauro (1995) argued that the main reasons for the limited development and slow progression in growth rates in many developing countries might be due to the high level of corruption. Combating corruption has been in the rhetoric and policy of Indonesia since the fall of Suharto in 1998. A number of anti-corruption campaigns were launched such as the creation of the Komisi Ombudsman Nasional (ombudsman) and the Komisi Pemeriksa Kekayaan Penyelenggara Negara (Assets Auditing Commission) (Sherlock 2002).

Respondents strongly expressed their negative perceptions of corruption, especially within government. “Government servants normally will demand for some money in order to approve licenses, to lease a shop or maybe someone who is selling their land”.Henderson and Kuncoro (2004) note that firms reported that more than 10% of their expenditure and time were used for bribery with local officials for ‘smoothing business operations. Moreover, respondents also claimed that money earned from tourism normally goes through multiple layers of different government officials resulting in bribery. Some local community programmes sponsored by government were highly inefficient and money was lost en-route between different government departments. This was evidenced by the corrupt use of state funds by Bali’s former tourism chief, who was found guilty for being reimbursed twice for international trade fairs for Bali in 2011 (Travel Trade News 2013). “It is a very serious issue at all levels and almost everywhere. It is almost the one important thing that we do not have any solution to.”

“Corruption has been going on for a long time and I am ashamed to say that it is embedded in the business culture here in Bali.” Respondents commented that it was common for local and foreign businesses to bribe just to get the process done rather than moving through the long and tedious correct procedures. Similarly, some also expressed regrets on their financial inability to open businesses due to high levels of corruption.

Respondents expressed that corruption had significantly affected the life of the majority of the local community. Locals were forced to save more money to bribe to ensure procedures were approved. This has unfortunately led to the exploitation of poorer locals, as they need extra fund to process their business. Our results show that issue of corruption can act as a barrier towards a fair attainment in socio economic prosperity among local communities. Result does not concur that socio economic prosperity will automatically be achieved once a destination is competitive as assumed in the model.

4.4. Involvement of Women

Bali tourism has created greater employment opportunities for women, both within the formal and informal sectors. Women who used to stay at home or were employed in agriculture are now employed in the hotel and restaurant sectors. The majority of respondents from Ubud and Legian gave positive feedback on the increased involvement of women in tourism and saw this as a blessing as women were able to escape from tiring manual labour in agriculture to work in the service industry:

“I feel happier now as I don’t have to work in the hot sun, farming crops. I am happy to have escaped all those [sic] hard work and sit in the air conditioned car every time I drive tourists around. As long as I give good service, I can even earn more from their tips. It makes me happy and proud to have this job.”

In addition, the increase in jobs and opportunities for women has also helped poorer families. For instance:

“My wife worked as a masseuse in a spa shop and earns about 5.6 million Rupiah (£300) each month. Although the salary is low it does help the whole family. If she is not working, I don’t think my salary will be enough for my whole family. I want my children to be better than us, so I need to work very hard to give them education.”

The findings show that tourism has given women more opportunities for businesses and independence as well as supporting the family. Moreover, locals are also benefiting from self-employment regarding opening their own businesses such as local warungs (food stalls) or small convenience stores. This seems to be really popular along Poppies Lane Street in Kuta, where most shops are locally owned. Ibu Oka in Ubud is one example of small successful businesses with little capital run by women famous for its local delicacy babi guling (Suckling pig). It began catering for local people but is now popular among tourists due to good reviews in Tripadvisor and the Lonely Planet guide books. Respondents who runs her own business as a seamstress, commented:

“I am very proud of myself as I can work here, earning a lot of tourists’ money and support my family. I even hire family members to help out during busy periods. As my shop is near my house, I can see my children whenever I want.”

This also confirms Hampton’s research (2013) on low capital entry costs in which modest requirements are needed for small scale development which later enhances local participation and lower economic leakages. Local women responded to tourism by opening businesses including food stalls or souvenir shops allowing more income to support their family as well as flexibility in carrying out activities within their families. However, there are also respondents who had opposing views of the increased involvement of women in tourism. Respondents who lives in a village commented, “The social structure is changing and the importance of family is declining. Younger people are leaving their village or parents behind wanting to work in touristic towns due to higher employment opportunities. They visit their homes less frequently due to their inflexible or busy schedules of working in a large company. Most do not attend religious rituals and ceremonies because of their long hours of shift.”

Additionally, other respondent also shared:

“most youngsters are happy with the economic benefits but older generations are unhappy about this. People nowadays rather pay fines to their banjar for failure in participation for ceremonial activities than doing less hours of work. Due to their limited time, they tend to buy offerings from shops and house chores; and rituals are being abandoned. It contradicts the traditional beliefs and the role of women.”

Besides, “the inflexible working time like night shifts or the ‘round the clock’ working hours created to meet tourists’ demands forced people with families to put up with it. Women who are married are forced to leave their children with family members.” This illustrates pressure from rigid working hours in hotels and restaurants which can distort their traditional family values and religious responsibilities. This finding is reinforces Wall’s argument (1996) that conflict arises from working hours and limits on the freedom to return to the village to perform cultural obligations.

The pressures on family values, the abandonment of household chores, infrequent visits to the village and declining participation in religious roles, all creates tension with traditional beliefs and roles of Balinese women. However, it can be argued that a change in the status of women is a useful indicator of the pattern and the direction of travel towards modernity. Those respondents who expressed negative views were villagers from Kintamani and older residents from Denpasar who arguably have been less influenced by Bali’s rapid changes and held more traditional views. Although the pressure of double burden could be argued as impacting women quality of life negatively due to job and family obligation, majority of the women interviewed express satisfaction in self-efficacy being involved in the tourism industry. The ability to provide for their family, children’s education, the ability to start small businesses, and the shifting from agriculture to the service sector brought a significant direct improvement in women’s QOL in Bali. These direct implications as a result of Bali being a competitive destination were evidenced in our study which corresponds to the Kim and Wicks model on achieving socio economic prosperity.

4.5. Opportunities for Locals

The majority of the respondents agreed on the opportunities locals gained, through the success of the tourism industry.Din (1992) argued that local entrepreneurial development is a natural process in reacting to tourists’ demands as it is only reasonable in terms of local residents’ strategic and locational advantages. Given the increasing number of hotels, restaurants and tourism-related businesses in Bali, local people perceived increasing prospects for employment, higher income or other opportunities:

“Locals also possess entrepreneurial outlook in them but on a smaller scale. The moment one hotel is developed; locals will soon have other businesses developed near them. Locals do their businesses in small scale in terms of car or motorbike rental, food stalls, local spa, local launderette, barber shop and many more. Locals do have opportunities but businesses are smaller due to their limited capital.”

This was strongly supported by respondents who expressed positively the opportunities for locals either in the form of small enterprises (souvenir shops, tattoo parlours, warungs, beach vendors providing services such as massage, hair plaiting or manicures) through to medium size enterprises such as hostels, local tour operators and bed and breakfast accommodation.

Stakeholder groups like DMOs, academics and those directly involved in tourism businesses also agreed that the younger generation has a brighter future as most are being educated, and tourism schools in Bali have opened to train young people. In addition, more opportunities exist as many locals have built partnerships with foreigners through friendship and their frequent visits to Bali. This is due to the implementation of rules for an easier processing of business license using local names since 1997. They open businesses and share the profit and workload. One of the most popular businesses is buying villas aiming to cater for high-end tourists.

Respondents voiced that a lot of locally owned hostel, was constantly trying to work with locals concerning purchasing food from local suppliers and contracting out washing linens to local micro businesses. This illustrates how business can create further opportunities and over time create stronger economic linkages with more tourist spend being retained within the Balinese economy. Residents in Kintamani however felt that they had fewer chances to gain tourism benefits due to their location and infrequent interactions with tourists. With increasing opportunities for the Balinese, tourism helps reduce poverty to some extent. According toGlobal Post (2018), poverty was defined as an income of less than £1.30 (US$ 2) per person. This was evidenced by the number of people living below the poverty level in Bali. The less than 5% poverty level among the 3.9 million residents in Bali was the lowest in Indonesia.

5. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

In this study, the most relevant parameters were extracted from these subjective approaches to form key interview questions, in order to get an in depth understanding of the socio economic prosperity of Bali as a destination. Previous research into destination competitiveness has unquestionably contributed knowledge towards building an understanding of its elements, structures, attributes and has provided an insight into the complexity of cluster issues. However, in the applicability and versatility of destination competitiveness frameworks, the inclusion of different attributes remains uncertain in respect of different destinations and there are still many interesting gaps that need to be explored. This paper addresses the research gaps on the effect of destination competitiveness on the social welfare of residents, and highlighted the importance of the inclusion of TNCs as a significant attribute especially in a developing nation like Bali.

Examining the socio-economic prosperity of a competitive destination is important as this signifies changes in wealth, education, the local environment and citizens’ welfare, as a destination develops. This may in turn affect consumption behaviour, changes in income, as well as the distribution of wealth, hence affecting the overall quality of life. This is especially relevant in Bali where the majority of local livelihoods depend on tourism. The assumption in Kim and Wicks’ framework that destination competitiveness will naturally bring better socio economic prosperity towards its citizen does not fully concur in this research. Although results show respondents appreciated the investment in infrastructure, buildings, roads and resorts by cluster actors such as TNCs which helped make Bali a successful and iconic destination in South-East Asia and their initial role in helping build the current industry, the over-dependence on external capital, issues of power, inequality and corruption all demonstrate negative results towards the livelihood of local people. The dissatisfaction of local communities with Bali’s unequal power distribution was a concern for the majority of respondents. Residents felt that there was nothing that could be done being the least powerful and least knowledgeable group of all stakeholders. The unequal power relations remained among stakeholders, with the distribution of power weighted towards the authorities, rather than the local communities in Bali. This further created a gap between those empowered, rich and well-connected and those powerless, poor locals. Furthermore, multiple layers of bureaucracy and the lack of incentives for those entrusted to fight corruption led to even more opportunities for corruption. The findings show that locals were obliged to save more money - even when they had sufficient to open their business - because of the extra funds needed for corruption and to ensure all procedures were approved. This process of corruption has unfortunately led to the exploitation of many poorer Balinese.

Additionally, results also show there was still a significant proportion of the host population who appeared to be taken advantage of, and who faced serious issues such as inequality, over-dependence on tourism, power differences and corruption. The population residing in villages furthest away from the southern tourist areas clearly expressed that there was little opportunity to even come into contact with tourists, let alone benefit from the industry. Villagers remained poor, as the benefits were limited to Bali’s southern region where good infrastructure and attractive TNC resorts were located. This poses further questions about conventional ‘trickle down’ theories of tourism benefits. Furthermore, the spatial concentration of mass tourism investment in southern Bali appears to have increased disparities among regions and classes. This concurs withTorres and Momsen (2005), who note that planned tourism development does not necessarily stimulate balanced regional development and equitable growth since the majority of the profits generated flow to the entrepreneurial elites, the government and TNCs causing inequality. The backward linkages in improving the life of the locals in Bali seem to be somewhat limited. Key themes that emerged through the interviews suggest that socio-economic prosperity is not guaranteed although a destination appears successful, as claimed in Kim and Wicks framework. Our findings show that the economic prosperity that is normally perceived from a successful competitive destination like Bali does not always translate to increased social welfare. This study has highlighted the importance of inclusion of cluster actors such as TNC as stated in Kim and Wicks’ conceptual framework, as this is highly reflective in developing destinations like Bali. Moreover, the results demonstrated partial agreement with the framework which naturally assume better socio-economic prosperity when destination is successful.

Similarly, it will be however naïve to assume that residents in Bali does not experience any form of life improvement from the development of tourism. Results shows the increased opportunities for locals regarding employment, new businesses, improved living conditions; and the increasing involvement of women. Respondents saw tourism as providing opportunities to open their own small businesses such as souvenir shops, tattoo parlours, local food stalls, or even medium size enterprises like hostels. The increase in the variety of different types of employment for locals also led to positive comments from respondents who felt better off with improved living conditions as well as improved education. The inclusion of the younger and the older generations into the workforce provided locals with a sense of security and optimism about the future. The increasing opportunities for women were all factors demonstrating an improvement in the Balinese QOL. The findings are however only valid in touristic areas such as Kuta, Legian, Sanur Denpasar and Ubud while are inapplicable for villagers from Kintamani. The benefits gained were spatially concentrated in South Bali, showing villagers elsewhere received limited benefits. The results show partial agreement with the theoretical aspects of the framework. The framework of tourism competitiveness leading to better socio-economic prosperity is partially demonstrated. Our research found that Bali’s success has brought an improvement in quality of life for the Balinese but only to a limited extent.

This paper is the first attempt to investigate the link between destination competitiveness and host community quality of life as seen on the Kim and Wicks model. Our research found that the Bali’s success has brought an improvement in QOL for the Balinese but only to a limited extent. The results do not entirely correlate with Kim and Wicks’ framework in which socio economic prosperity is naturally assumed when a destination is competitive. A successful and competitive tourism destination does not always mean better welfare for its residents as is shown clearly in the Bali case study, thus justifying the importance of taking a further step and analysing the links between destination competitiveness and residents’ QOL. This finding also support the recent work ofKubickova et al. (2017) indicating increase in economic freedom does not mean better welfare for the citizens. Understanding destination competitiveness is essential to facilitate effective destination management as seen by recent research such as du Plessis et al. (2017), there is however also a need to investigate if the host residents are benefiting from the development itself. This paper therefore has closed some of the research gap by investigating the social welfare impacts affecting Bali’s residents resulting from destination competitiveness based on the model.

Andereck K.L.; Vogt C.A. (2000), "The relationship between residents' attitudes toward tourism and tourism development options", Journal of Travel Research, Vol. 39, No. 1, pp. 27-36. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728750003900104

Andereck K.L.; Nyaupane G.P. (2011), "Exploring the nature of tourism and quality of life perceptions among residents", Journal of Travel Research, Vol. 50, No. 3, pp. 248-260. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287510362918

Armenski T.; Dwyer L.; Pavluković V. (2017), "Destination Competitiveness: Public and Private Sector Tourism Management in Serbia", Journal of Travel Research, Vol. 57, No. 3, pp. 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287517692445

Baker K.; Coulter A. (2007), "Terrorism and tourism: The vulnerability of beach vendors' livelihoods in Bali", Journal of Sustainable Tourism, Vol. 15, No. 3, pp. 249-266. https://doi.org/10.2167/jost643.0

Bali this week (2019), 3.5 Million Foreign Tourist Arrivals Until July, viewed 15 October 2019 , https://balithisweek.com/2019/09/3-5-million-foreign-tourist-arrivals-until-july/

Bali Tourism Authority (2004), Number of tourist’s arrivals after bombing, viewed 15 February 2019 , http://www.balitourismboard.org/stat_arrival.html

Becker G.S.; Philipson T.J.; Soares R.R. (2003), "The quantity and quality of life and the evolution of world inequality", National Bureau of Economic Research https://doi.org/10.3386/w9765

Camfield L. (2004), "Measuring SWB in developing countries", in Glatzer, W., Von B., S. and Stoffregen, M (Ed.) Challenges for the quality of life in contemporary societies , Netherlands: Kluwer Academic https://ueaeprints.uea.ac.uk/id/eprint/24935

Chin W.L.; Haddock-Fraser J.; Hampton M.P. (2015), "Destination competitiveness: evidence from Bali", Current Issues in Tourism, Vol. 20, No. 12, pp. 1-25. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2015.1111315

Crouch G.I.; Ritchie J.R. (1999), "Tourism, competitiveness, and societal prosperity", Journal of Business Research, Vol. 44, No. 3, pp. 137-152. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0148-2963(97)00196-3

Costanza R.etal. (2008), "An Integrative approach to Quality of Life Measurement, Research and Policy", Surveys and Perspectives Integrating Environment and Society, Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 17-21. https://doi.org/10.5194/sapiens-1-11-2008

Diener E.; Suh E. (1997), "Measuring quality of life: Economic, social, and subjective indicators", Social Indicators Research, Vol. 40, No. 1, pp. 189-216. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1006859511756

Diener E.; Napa-Scollon C.K.; Oishi S.; Dzokoto V.; Suh E.M. (2000), "Positivity and the Construction of Life Satisfaction Judgments: Global Happiness is not the Sum of its Parts", Journal of Happiness Studies, No. 1, pp. 159-176. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010031813405

Din K.H. (1992), "The 'involvement stage' in the evolution of a tourist destination", Din, K.H. (1992), “The 'involvement stage' in the evolution of a tourist destination”, Tourism Recreation Research, Vol. 17, No. 1, pp. 10-20. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.1992.11014637

du Plessis E.; Saayman M.; van der Merwe A. (2017), "Explore changes in the aspects fundamental to the competitiveness of South Africa as a preferred tourist destination", South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences, Vol. 20, No. 1, pp. 11. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajems.v20i1.1519

Dwyer L.; Kim C. (2003), "Destination competitiveness: determinants and indicators", Current issues in tourism, Vol. 6, No. 5, pp. 369-414. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500308667962

Dwyer L.; Forsyth P.; Rao P. (2000), "The price competitiveness of travel and tourism: a comparison of 19 destinations", Tourism Management, Vol. 21, No. 1, pp. 9-22. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(99)00081-3

Ellis S.; Sheridan L. (2014), "A critical reflection on the role of stakeholders in sustainable tourism development in least-developed countries", Tourism Planning and Development, Vol. 11, No. 4, pp. 467-471. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2014.894558

Feenstra R.; Hanson G. (1996), "Globalization, outsourcing and wage inequality", The American Economic Review, Vol. 86, No. 2, pp. 240-245. https://doi.org/10.3386/w5424

Global Post (2018), Indonesia –Bali’s riches expose wealth gap viewed 25 April 2019 , http://www.gpiatlantic.org/conference/proceedings/thinley.htm

Go F.M.; Govers R. (2000), "Integrated quality management for tourist destinations: a European perspective on achieving competitiveness", Tourism Management, Vol. 21, No. 1, pp. 79-88. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(99)00098-9

GPI Atlantic (2005), Rethinking Development, Local Pathways to Global Well-being, viewed 7 October 2019 , http://www.gpiatlantic.org/conference/proceedings/thinley.htm

Hampton M.P.; Jeyacheya J. (2015), "Power, Ownership and Tourism in Small Islands: evidence from Indonesia", World Development, Vol. 70, pp. 481-495. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.12.007

Hassan S.S. (2000), "Determinants of market competitiveness in an environmentally sustainable tourism industry", Journal of travel research, Vol. 38, No. 3, pp. 239-245. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728750003800305

Henderson J.V.; Kuncoro A. (2004), "Corruption in Indonesia", The National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) https://doi.org/10.3386/w10674

Hitchcock M. (2000), "Ethnicity and tourism entrepreneurship in Java and Bali", Current Issues in Tourism, Vol. 3, No. 3, pp. 204-225. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500008667873

Kayat K. (2002), "Power, social exchanges and tourism in Langkawi: rethinking resident perceptions", International Journal of Tourism Research, Vol. 4, No. 3, pp. 171-191. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.375

Kim N.; Wicks B.E. (2010), "Rethinking Tourism Cluster Development Models for Global Competitiveness", International CHRIE Conference-Refereed Track https://scholarworks.umass.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1370context=refereed

Kim K.; Uysal M.; Sirgy M.J. (2013), "How does tourism in a community impact the quality of life of community residents?", Tourism Management, Vol. 36, pp. 527-540. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2012.09.005

Kubickova M.; Croes R. , Rivera M. (2017), "Human agency shaping tourism competitiveness and quality of life in developing economies", Tourism Management Perspectives, Vol. 22, pp. 120-131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2017.03.002

Kuncoro A. (2004), "Bribery in Indonesia: some evidence from micro-level data", Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies, Vol. 40, No. 3, pp. 329-354. https://doi.org/10.1080/0007491042000231511

Mauro P. (1995), "Corruption and growth", The quarterly journal of economics, Vol. 110, No. 3, pp. 681-712. https://doi.org/10.2307/2946696

McGillivray M. (2007), "Towards a measure of non-economic well-being achievement", Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, England, pp. 133-153. https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9780511488986.007

NEF ((2013),), Happy Planet Index viewed 21 February 2019 , http://www.happyplanetindex.org/

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development ((2019),), Making the most of tourism in Indonesia to promote sustainable regional development" ( 15 October 2019 ) http://www.oecd.org/officialdocuments/publicdisplaydocumentpdf/?cote=ECO/WKP(2019)4

Pagdin C. (1989), "Assessing Tourism Impacts in the Third World: a Nepal Case Study", Progress in Planning, Vol. 44, No. 3, pp. 185-226. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-9006(95)00004-6

Pearce D.G. (2014), "Toward an integrative conceptual framework of destinations", Journal of Travel Research, Vol. 53, No. 2, pp. 141-153. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287513491334

Travel Reuters (2011), The close proximity between Tanah Lot and Pan Pacific Nirwana Resort, viewed 4 May 2019 , http://www.balistarisland.com/Bali-Adventure-Sightseeing/Nirwanagolf.html

Shackman G.; Liu Y.L.; Wang X. (2005), "Measuring a quality of life using free and public domain data", Social Research Update, Vol. 30, No. 8, pp. 1062-1075. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167204264292

Sherlock S. (2002), "Combating corruption in Indonesia? The ombudsman and the assets auditing commission", Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies, Vol. 38, No. 3, pp. 367-383. https://doi.org/10.1080/00074910215532

Torres R.; Momsen J. (2005), "Planned tourism development in Quintana Roo, Mexico: Engine for regional development or prescription for inequitable growth?", Current Issues in Tourism, Vol. 8, No. 4, pp. 259-285. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500508668218

Travel Trade News (2013), Former Bali Tourism Chief Jailed viewed 17 April 2019 , http://www.ittn.ie/bulletins/former-bali-tourism-chief-jailed/

Veenhoven R. (2007), "Subjective Measures of Well-being", Palgrave Macmillan, London https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230625600_9

Wall G. (1996), "Perspectives on tourism in selected Balinese villages", Annals of Tourism Research, Vol. 23, No. 1, pp. 123-137. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(95)00056-9

World Health Organisation (2019), WHOQOL: Measuring Quality of Life, viewed 15 October 2019 , https://www.who.int/healthinfo/survey/whoqol-qualityoflife/en/

Appendices

Interview Questions for Bali

Polite conversation to let respondents at ease…. How long have you been in this job? Do you like it? What are your responsibilities? Maybe get him to speak up on his background and experience.

Official data shows Bali is wealthier since it became a popular tourist’s destination. Do you feel better off? How so?

Do your children / younger generations /you have more employment opportunity as compare to the past? (Ability to switch jobs)

What is your opinion of getting a job like yours in the tourism industry?

Is it easy to get a managerial/lower rank job (depends on previous question) in the tourism industry? Has this changed over the past years? If so, why do you think this is?

Do you feel that tourism has benefited Balinese people overall? In what way(s)? Schooling? Health? Sanitation? Public utilities? Water sources? Popularity? (Government statistics shows improvement in terms of health and sanitation)

What about the problems from tourism? How does it affect the locals?

Some people feel that government (Central and provincial) are exploiting/ taking advantage of tourism. What do you think?

Do locals feel that tourism industry is dominated by foreign owners? Do you feel that it is difficult to compete with international chains?

Do you think the government should limit the number of Multinational Corporations in Bali? (Bali highly dependent on external investment Why so? (To check on the importance of MNC in developing countries -Porter emphasised)

Without the investment of Multinational companies, would you think Bali will be successful? If not, why not? What make a difference?

Do you feel part of/involved in the decision making process (in terms of votes and participation) when it comes to tourism development? (Community participation as emphasis in cluster theory)

What do you think are the difference between tourists staying in a 5 star hotels and those staying in local bed and breakfast/ accommodation?

How do you think tourists income or behavior (perhaps their existence) have affected the life of the locals? (benefiting or worsening)

If there is no tourism, how different would your life be?

Do you think that tourism is one of the factors that increase the gap between the rich and the poor?

Do you think tourism improves the quality of life in Bali? Does it help with the poverty level?

Do you think that money earned by Bali tourism is being reinvested back to Bali? Why so? (To check on their opinion on whether most of the profit earned by tourism are sent to bigger regions like Jakarta and the rest of Indonesia)

As Bali became more and more popular, does it have any effect on your day to day life? (before and after fame to test if their quality of life changes)

What do you think are the reasons Bali being such a successful destination?

From your point of view, do you think domestic customer needs and local resources plays an important role in contributing towards Bali being such a popular destination?

Do you feel empowered (more control over their life)?

Do you see corruption as an issue in Bali? Why so?

Are you happy or satisfy with your life? If not, what would improve matters? (Opportunities to undertake meaningful, engaging activities)

From your point of view in which sector of tourism do you think money is most likely to stay within the community?

What is your opinion on “Tourism improving the quality of life of Balinese”? And how can this be seen, if at all?

As Bali gradually became such a competitive destination, how do you think this has affected the lives of the locals? If so, in what main ways?