INTRODUCTION

In the hotel industry, the use of information technology (IT) has dramatically changed the entire sector’s way of life (Garrigos-Simon, Galdon and Sanz-Blas 2017). More specifically, this technological revolution has impacted both hoteliers (i.e., providing management and marketing support) and consumers, who are increasingly changing their habits.

Today, a growing number of tourists are using the internet to prepare their trips, find hotels, and make reservations (Jung, Chung and Leue 2015). Therefore, an online presence of tourism organizations is necessary to gain a large market segment, communicate with customers about offers, strengthen relationships, as well as establish a destination appeal and reflect a smart tourism destination (Mandić and Praničević 2019).

In this sense, websites are considered an important gateway between hotels and current and potential guests and an important marketing tool for promoting and selling hotels’ products and services. Thus, many academic researchers have discussed the importance of evaluating websites’ effectiveness and performance while accounting for features such as functionality and usability, responsiveness, interactivity, information on products and services, design, booking and online transactions, and ease of use (Sun, Fong, Law and He 2017). A high quality website has a positive effect on customer satisfaction and trust (Orel and Kara 2014), which in turn affects visitors’ decisions to revisit and buy the brand’s products and services (Law 2019).

Previous research has suggested that sociodemographic characteristics such as gender and age influence customers’ online experience and behavioural intentions (Tarhini, Hone and Liu 2014). For instance,Khan and Rahman (2016) found that men and women perceive brand experiences differently. More specifically,Kim, Kim and Kim (2018) revealed that women place more importance on hotel choice factors such as room quality and staff service than men do.Chan and Wang (2015) stated that young consumers were found to be more brand conscious, requiring a strong need for a brand’s novelty, compared with older consumers. Therefore, sociodemographic information related to website users plays a crucial role in designing business strategies (Saste, Bedekar and Kosamkar 2017), and thus providing a website that meets users’ needs and expectations.

Although the evaluation of hotel websites has gained ample attention from academic researchers, most of them have utilized web performance tools to measure hotel website performance (e.g., webpagetest.org, yslow.org). Thus, these studies did not analyse customers’ preferences and the importance that customers give to hotel website features. Furthermore, studies on changes in hotel website evaluation related to recent mutations in users’ habits have been sparse.

This paper seeks to provide an overall understanding of hotel website evaluation based mainly on users’ perceived importance of crucial hotel website features and how this importance may differ by gender, age as well as frequency of internet access. To our knowledge, no previous research has examined the impact of sociodemographic and psychographic characteristics on the perceived importance of hotel website features.

This study’s main contribution is to provide an overall understanding to practitioners, marketers, hoteliers, and managers regarding the most important website features from users’ perspectives. This gives new insights to hoteliers to make importance to specific features than others, provide accurate information, ensure high-quality communication, better respond to users’ needs and expectations, and remain competitive in the marketplace. Moreover, this study can be used by academics and researchers as a reference for further research into extending and/or reconstructing hotel website evaluation models.

1. LITERATURE REVIEW

This section begins by discussing recent studies related to hotel websites, their importance in the hotel industry and how they are evaluated. Then a comprehensive model for hotel website evaluation is provided based on users’ perceived importance of hotel website features. Furthermore, the section discussed the possible effects of demographic characteristics (i.e. gender, age, frequency of internet access) on the importance given to website features.

1.1. Hotel websites and their importance in the hotel industry

With the rapid development of the internet, online platforms remain the most effective management, sales, and marketing channels for hotels (Mandić and Praničević 2019). These platforms allow hotels to provide relevant information on various products and services, reach customers directly, increase their market share and profits, decrease the costs of distribution, and enhance their competitiveness in the marketplace (Ting et al. 2013).

Furthermore, with the growing number of internet users, hotel websites represent the preferred tool for consumers to plan and book their trips. More specifically, hotel websites are considered the first point of contact between potential customers and hotels (Sun et al. 2017).

Previous studies revealed that over 50% of users book through hotel websites or online travel agencies (Pan, Zhang and Law 2013). Therefore, the quality of hotel websites is fundamental in a competitive business environment. In this regard,Bilro Loureiro and Ali (2018) stated that a website’s information/content and design/visual appeal has a significant effect on online engagement (i.e., cognitive processing, affection, and activation), which mediates the effect of stimuli on customers’ brand advocacy.Al-Shami et al. (2019) revealed that social network websites have a positive impact on innovation capacity, which mediates the relationship between social networks websites and hotel’s performance. Thus, a well-designed hotel website that satisfies first-time visitors’ impressions is more likely to positively influence users’ attitudes, causing users to stay on the same website for trip planning.

1.2. Models used for hotel websites evaluation

In the hotel industry, many researchers have focused on hotel website features to assess website service quality and effectiveness. Research in this field has continued with the development of models that encompasses a variety of items. For instance,Qi, Law and Buhalis (2013) argued that functionality and usability dimensions are equally important to evaluate the performance of hotel websites.

Evaluating hotel website functionality entails assessing the capacity of the website to offer appropriate content and information through its features (Wong, Leung and Law 2018), while hotel website usability is defined as the level of ease of use and conviviality of the design (Qi et al. 2013).

Sun et al. (2017) revealed that the majority of analysed articles on website evaluation in hospitality and tourism for the 2000-2015 period stressed the user interface, marketing effectiveness, and website quality.Zhang, Cheung and Law (2018) used criteria to evaluate the functionality performance of destination marketing websites of smart tourism cities. Additionally,Law (2019) examined the chronological changes in hotel websites evaluation models and revealed that among many expressions used to illustrate the concept, information quality has been the main focus of academic researchers.

1.3. Hotel website features

The current study adopted the evaluation measurements of hotel websites from previous literature, and selected the website features that were most used according to the evidence and suited to the purpose of this study. Each of them will be explained in the following sections.

1.3.1. Design

Prior studies revealed that there is a significant relationship between a hotel website’s design and customers’ attitudes toward the hotel. For instance,Khalifa and Hewedi (2016) stated that a hotel website’s design, interactivity, and visual appeal affect its competitiveness, which in turn affects the customers’ purchasing intention. Thus, the manipulation of different web interface design factors could establish customer confidence. Additionally,Hao et al. (2015) studied the visual appeal of hotel website designs. They revealed that web pages with large pictures and little text are particularly preferable to Chinese users.

1.3.2. Ease of use

Evidence suggests that ease of use is one of the most important factors for users to pursue navigation of a hotel’s website. Ease of use refers to the simplicity of navigation through a hotel website to reach the desired products and services (Panda, Swain and Mall 2015). Thus, the easiness of a website’s navigation provides better understanding of its contents, which could be an influencing factor in customer satisfaction and loyalty.

Moreover, an easy-to-use hotel website should include ease of understanding and ease of operation. Thus, a page’s load time has the potential to influence users’ attitudes about the hotel, particularly for first-time visitors (Baraković and Skorin-Kapov 2017). Generally, users abandon a website that does not load in the expected time.

1.3.3. Privacy

Previous literature has suggested that ensuring privacy and security of service and information, such as payment procedures, is crucial to ensure customers’ positive attitude and continued perusal of the hotel website, thus impacting their intention to make a purchase (Hahn, Sparks, Wilkins and Jin 2017).

Furthermore, during their stay, guests were willing to share their personal information, such as location, when searching for sightseeing areas (Harris, Brookshire and Chin 2016). Hotels should therefore manage and improve the privacy levels and permissions of location-based services so that customers feel confident about a given hotel’s website.

1.3.4. Corporate information

Many researchers have shown the need to make corporate information available, such as presenting the history, mission, and collaborations of the hotel or hotel chain (Poon and Lee 2012), as well as awards and certifications.

To analyse this factor,Ramos et al. (2016) developed a framework to characterize hotel websites. They identified exhaustive dimensions, such as corporate information, which encompass several indicators, such as awards received by the hotel and press news. These types of information could increase the users’ perceived website trustworthiness, which in turn could increase their willingness to make a reservation.

1.3.5. Information on products and services

Information on products and services is considered the most important feature for website effectiveness. Tourists seek information about a hotel’s products and services, such as description, prices, pictures, general hotel facilities, room facilities, food and beverage options, and entertainment facilities (Ramos et al. 2016). Potential guests also want to compare a hotel’s features with alternatives to assure themselves that they are choosing the best option.

Therefore, the website should provide transparent and adequate information, maintain a positive and beneficial image in consumers’ minds, and sufficiently respond to customers’ queries and expectations(Poon and Lee 2012). A hotel can differentiate itself from competitors by providing high-quality information about its products and services.

1.3.6. Booking information and reservations

Many previous studies have considered the booking and reservation function the primary feature of hotel websites. For example,Khalifa and Hewedi (2016) stated that to deal with foreign customers, hotels should have websites that support online booking and payment.

Currently, hotels try to eliminate intermediaries and drive reservations directly to their own websites by improving and facilitating the purchasing process. This improvement increases electronic trust (i.e., online confidence in dealing with the website and truthful payment procedures) and online booking intentions.

Furthermore, hoteliers prefer direct distribution for their products and services to communicate with customers directly and provide a personalized offer. This form of communication could decrease the costs of distribution (i.e., commission fees required by online travel agencies and other intermediaries), increasing the hotel’s profitability(Stangl, Inversini and Schegg 2016).

1.3.7. Information on the surroundings

Information on the hotel’s surroundings should be part of the hotel’s website. For instance,Khalifa and Hewedi (2016) discussed how customers are satisfied with this informational content and explained how content helps customers in their decision-making process. These features encompass travel ideas, sightseeing areas, weather information, transportation, maps and itineraries, nearby restaurants, shopping, medical and health information, and other helpful details (Ramos et al. 2016). Additionally, customers perceive a hotel to be more reliable if its website includes such information. Thus, content should always be updated.

1.3.8. Contact information

Contact information is one of the most popular attributes of hotel websites. This feature includes the hotel’s physical address, email address, phone numbers, and other relevant details. Many researchers have considered this feature important (Ramos et al., 2016) because customers need to know where the hotel is located, and how to contact the hotel quickly and directly by phone. Contact information represents an important channel of communication between hotels and their customers (Ramos et al. 2016).

1.3.9. Social media pages

In the hotel industry, social media platforms are an important tool for marketing and promotion (Zeng and Gerritsen 2014), allowing interaction, creation, and exchange of user-generated content. On social media pages, user-generated content plays a key role in influencing customer decision-making as well as enhancing brand image and increasing sales.

Hence, a growing number of hoteliers are starting to incorporate links to social media, such as Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and TripAdvisor on their websites to reach larger audiences, improve relationships, and involve customers in their brands. These steps allow managers to understand what customers expect from the organization (Escobar-Rodriguez and Carvajal-Trujillo 2013).

1.3.10. Customers’ feedback options

Customer feedback is another important dimension of a hotel website. This dimension can strengthen the relationship between customers and hotels (Hahn et al. 2017), and thus enhance customers’ loyalty. Features such as feedback forms, customer surveys, and loyalty systems are relevant to assess customers’ satisfaction in and expectations of hotels’ products and services and determine how hoteliers can improve their offers (Wong et al. 2018).

1.4. The impact of age, gender, and frequency of internet access on the importance of hotel website features

The possible effects of various sociodemographic (i.e., gender, age) and psychographic characteristics (i.e., frequency of internet access) could have on the perceived importance that users attribute to hotel website features were also tested.

Gender effect. Gender has been widely considered a key variable in marketing and consumer research. In fact, some studies have acknowledged notable differences in male and female responses and thus in behavioural intentions, whereas others did not find significant differences in behaviour between genders.

For instance,Kim et al. (2018) stated that women are more concerned with hotel choice factors such as staff service and room amenities than men are.Khan and Rahman (2016) argued that men and women behave differently toward transactions and banking services. Particularly, men are less willing to take risks compared with women. Understanding such differences will help brands provide a website that meets users’ expectations.

However,Roozen and Raedts (2018) found no significant impacts of sociodemographic variables such as gender and age on travellers’ decision-making processes. This is supported bySultana and Imtiaz (2018)’s work showing no significant difference between men and women in overall internet usage pattern, apart from internet games and commercial transactions. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H1: Gender has an impact on the perceived importance of hotel website features.

Age effect. Age differences have been observed to lead to different attitudes and decision-making of both consumers and brands. More specifically, the differences in attitude in terms of technology adoption and level of use can be explained by variations between younger and older users regarding their perceptions of the usefulness, interest, and ease of use of a given technology(Wong et al. 2012).

For instance,Bolton et al. (2013) stated that younger consumers prefer to interact with technology more than older people do.Mang, Piper and Brown (2016) found that opposed to older consumers, younger people exhibit increased usage of mobile technology related to the tourism industry. Additionally,Khan et al. (2020) revealed that hotel websites and social media positively affect hotel brand loyalty in the case of young customers. Other researchers, such asKim (2016), who analysed behavioural intentions toward hotel tablet apps, found that demographic characteristics such as age did not play significant moderating roles between an app’s ease of use, usefulness, credibility, and subjective norm and behavioural intentions. However, age-related differences were perceived for other specific hotel tablet app functions. In view of the differences between younger and older users, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H2: Age has an impact on the perceived importance of hotel website features.

Frequency of internet access effect. Previous studies have considered internet consumers to be the key research subjects that allow firms to understand users’ expectations and behavioural intentions. Users who have prior experience with internet-based systems form habits that impact their behavioural and continuance usage intentions (Amoroso and Lim 2017). In this sense,Cheung and Thadani (2012) found that familiarity and involvement with internet platforms were the two most important factors in consumers’ decision-making processes.Chopdar and Sivakumar (2019) stated that habit has the strongest effect on use behaviour and continuance usage intention of shopping apps.

Additionally,Teng, Ni and Chen (2018) considered heavy and light internet users to compare the significant attributes of e-service capes and determine their relationship with purchase intentions. Their results revealed that for heavy users, interactivity was the strongest factor, followed by aesthetic appeal, layout, and functionality. In comparison, aesthetic appeal was the only important factor for light users. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed.

H3: Frequency of internet access has an impact on the perceived importance of hotel website features.

1.5. Research objectives

This manuscript has two main objectives. First, to analyse the relative importance for hotel guests of the 10 hotel website features derived from the previous literature review. Second, to investigate the impact of gender, age and frequency of internet access on the importance given to the aforementioned features.

2. METHODOLOGY

2.1. Data collection procedure

In this study, our objective is to evaluate hotel website features. For this aim, a research questionnaire was developed in order to collect responses from tourists in Agadir, Marrakech and Essaouira, the three main tourism destinations in Morocco. This country have been chosen for our case study since most researches related to the evaluation of hotel website features have been carried out in developed countries such as the USA, UK, Australia and China. However, few studies have been conducted in developing countries. Particularly, no such studies have been conducted in the African continent. Morocco was chosen given its touristic potential, as because of being the most visited destination in Africa with 13 million international tourist arrivals (UNWTO, 2019).

The questionnaire contains 10 features to evaluate hotel website effectiveness, namely: design, ease of use, privacy, corporate information, information on products and services, booking information and reservations, information on the surroundings, contact information, links to social media pages, and customers’ feedback options.

A self-administered questionnaire was distributed at the reception of all types of hotels, airports, commercial, entertainment complexes and the main city sights of the aforementioned cities. Then they were hand-collected by the research assistants and one of the authors of this study. Respondents were asked to express their perceived importance regarding the features of hotel websites. Questionnaires distributed were written in English, Spanish and French.

Data were collected from May to November 2019. 1000 questionnaires were distributed. A total of 437 responses were collected, among which 31 were discarded for several reasons (responses missing in the questionnaire, etc.). Thus, the final sample size contained 406 valid responses, for a response rate of 40.6%.

2.2. Description of the sample

Among the respondents, 41.13% were male, and 58.86% were female. The majority of the respondents are between 36 and 45 years (32.26%). The two most frequent countries of origin were France (17.98%) and Morocco (15.02%). Most respondents had a higher education degree (37.43%). 42.61% of respondents accessed the internet between 1 and 3 hours per day (Table 1).

2.3. Measurements

All features were derived from previous literature. Single-item measures were used as they were deemed appropriate and recommended for use by many researchers when the research objective is to attain a general impression of a construct (Diamantopoulos et al. 2012). The current study focused on the perceived importance of general website features of hotels. Thus, the use of single-item is adequate for this research. Furthermore, single-item measures can help decrease the length of the questionnaire, thus avoiding low response rates from participants (Cheah et al. 2018) and increase the potential of survey completion, specifically regarding respondents who are difficult to recruit (Drolet and Morrison 2001;Van Dolen and Weinberg 2017).

All items are based on a five-point Likert-scale ranging from not at all important (1) to very important (5). The 10 features can be found inTable 2.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Analysis of users’ perceived importance of features

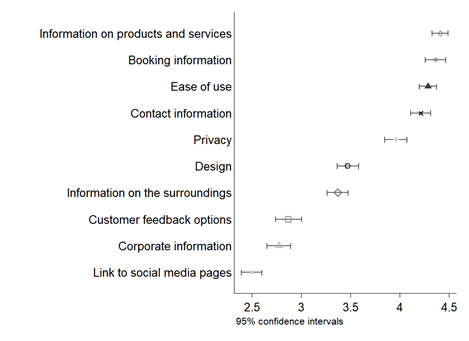

Table 3 shows users’ perceived importance of hotel website features. Users perceived information on products and services (mean=4.40), booking information and reservations (mean=4.36), ease of use (mean=4.28), and contact information (mean=4.21) as the four most important hotel website features, followed by privacy (mean=3.96), design (mean=3.47), and information on the surroundings (mean=3.36). Customers’ feedback options (mean=2.87), corporate information (mean=2.77) and links to social media pages (mean=2.49) were all given an average value below 3, which means that users did not think that these features were especially relevant.

In order to understand the relative importance of each of the aforementioned 10 features as well as their significance, the mean and their confidence intervals were calculated (Table 4 andFigure 1).

Table 4 shows that there are three groups of features: First, a group of four features with a mean that is well above 4: information on products and services, booking information and reservation, ease of use, and contact information. A second group comprised three features with a mean above 3.5 and below 4: privacy, design, and information on the surroundings. Last, a third group of features with a mean under 3 in a range of 1 to 5: customer feedback options, corporate information, and links to social media pages.

In the cases in which the 95% confidence interval of one feature does not overlap with the confidence interval of the next feature, it can be stated that there is a significant difference between these two features. This is the case, for example, with privacy [3.84, 4.07] and design [3.36, 3.58].

For other cases in which there was a certain overlap between the confidence intervals of two consecutive factors (seeFigure 1), an additional paired t-test was performed in order to analyse if there was a significant difference or not. In this sense,Table 5 shows that there is a significant difference between the following features: contact information-privacy, privacy-design, information on the surroundings-customers’ feedback options, and corporate information-links to social media pages, while no significant difference is shown between information on products and services-booking information and reservations, booking information and reservations-ease of use, ease of use-contact information, design-information on the surroundings, as well as customers’ feedback options.

3.2. The impact of demographic characteristics on the importance of features

A one-way ANOVA was used to analyse whether the perceived importance of hotel website features differs by gender (seeTable 6).H1, which predicted that gender would have an impact on the perceived importance of hotel website features, was not significant, since all p values were greater than.05. Therefore, gender does not influence the importance given by guests to hotel website features.

In a similar vein, and in order to analyse whether the perceived importance of hotel website features differs by age (seeTable 7), a one-way ANOVA was used. H2, which predicted the impact of age on the perceived importance of hotel website features, was partially supported. In fact, based onTable 7, age was found to have no significant effect on the perceived importance of five of the analysed features: privacy, information about products and services, booking information and reservations, information about the surroundings, and contact information.

However, age did have an impact on the importance of the other five features.Table 7 shows that younger tourists (18-25 years) attributed higher importance to design (mean= 4.5, F= 3.28, p< .05) and links to social media features (mean=3.9, F=9.11, p <.001) compared with the oldest age category (56 years or above) (mean=3.25and =2.10). In contrast, older tourists (56 years or above) (mean=4.51, F=8.17p <.001; mean=3.01, F=4.9, p <.01) were more likely than younger tourists (18-25 years) (mean=4.3and =1.4) to give more importance to the corporate information features and ease of use of websites.

In terms of the availability of a customer feedback option, younger tourists (26-35 years) (mean=3.23, F=3.05, p< .05) and those 18-25 years old were most concerned (mean=3.2), followed by those in the 36-45 and 46-55 years age categories, whereas older tourists (56 years or above) (mean=2.56) were less interested in this website feature.

Last, a one-way ANOVA was also used to analyse whether the perceived importance of hotel website features differed by frequency of internet access (seeTable 8).The results showed a significant impact of frequency of internet access on the importance attributed to three of the ten features: ease of use, privacy, and links to social media.

Tourists that had access to the internet for less than one hour per day were more likely to attribute importance to ease of use (mean= 4.59, F=8.53, p< .001) and privacy (mean=4.21, F=3.89, p< .01), whereas tourists that had access to the internet for more than 6 hours per day attributed more importance to links to social media (mean=3.13, F=4.08, p< .01).Therefore, H3, which predicted the impact of frequency of internet access on the perceived importance of hotel website features, was partially supported.

4. DISCUSSION AND IMPLICATIONS

Among the ten hotel website features analysed, guests perceived four to be important: information on products and services, booking information and reservations, ease of use, and contact information (seeTable 9).

The first three features were expected. Thus, as stated, hotels should properly present their products and services with detailed and up-to-date information and images that give guests a preview of their stay (Poon and Lee 2012). Second, hoteliers should give more importance to booking and reservations to increase direct reservations from their websites and try to eliminate intermediaries (Khalifa and Hewedi 2016). Third, hoteliers should provide easy-to-use websites that can be easily explored and respond to users’ specific requirements, encouraging users to continue perusing the same website (Khalifa and Hewedi 2016).

Additionally, when designing a website, hoteliers should provide clear contact information for the hotel, such as the physical address, phone numbers, email, and maps and itineraries (Ramos et al. 2016). Although some of this contact information can be found on websites such as Google Maps, users should also have easy access to it on the hotel’s website. For example, guests may try to contact the hotel by email or by telephone or may prefer more detailed information on how to arrive at the hotel than that provided by standard applications like Google Maps.

Privacy was valued by the participants but was not as important as expected. This could be explained by the different levels of internet usage. Our results show that tourists that access internet more than 6 hours per day were less concerned by privacy feature. It seems that privacy is of greater concern to those who are less tech-savvy.

Furthermore, design and information on the surroundings were also perceived relevant with means above 3.5 and below 4.Thus, hoteliers should provide well-designed and attractive websites as they represent the first point of contact with customers, since these features may leave consumers wanting to find out more details about the hotel’s products and services and ultimately making a reservation (Hao et al. 2015). Additionally, information on the surroundings, such as sightseeing areas, nearby restaurants, transportation, and weather, should usually be updated as these details provide helpful information to customers in their decision-making process and during their stay (Khalifa and Hewedi 2016).

Last, customer feedback options, corporate information, and links to social media pages were all perceived as much less important, with means below 3. Therefore, users considered customer feedback options unimportant. This could be explained by the existence of specific websites (such as TripAdvisor) on which guests can offer their opinions. Most guests usually tend to prefer websites like TripAdvisor more than hotel’s website in order to provide feedback (Filieri, Alguezaui and McLeay 2015).

Regarding corporate information, guests clearly use the website for functional reasons (e.g., booking, finding information). Thus, corporate information about the hotel provides little value to them. For links to social media pages, the low importance (2.50 in a 1 to 5 range) could be due to two reasons. First, when guests want to access a hotel’s social media page, they may first access the social media website (e.g., Twitter or Facebook) and then look for the hotel’s profile. Second, users may not be interested in the hotel’s social media profiles. If they are already on the website, they probably are no longer interested in accessing the publications on Twitter or Facebook. However, these possibilities need to be confirmed in further studies.

The study investigated the impact of gender, age, and frequency of internet access on the importance attributed to hotel website features. The result revealed no significant effect of gender on the perceived importance of hotel website features. This correlates withRoozen and Raedts (2018)’ study showing no significant influences of gender on travellers’ decision-making processes. However, our result contradicts the work ofKim et al. (2018) stating that there is a significant difference between men and women regarding hotel choice factors.

This study showed that younger tourists attribute significantly greater importance to design, links to social media pages, and customer feedback compared with older tourists. Meanwhile, ease of use and corporate information features attract the interest of older tourists more than those in the youngest age category. This result aligns withKhan et al. (2020)’s work revealing a significant difference between younger and older customers in using hotel websites. Therefore, hoteliers should provide a website that meets different age category expectations.

Additionally, this study revealed that tourists that access the internet less than one hour per day attribute more importance to ease of use and privacy features compared with tourists that access the internet more than 6 hours. The more frequent internet users were more concerned with links to social media, a result that corresponds with the work ofCheung and Thadani (2012) showing that familiarity and involvement with internet platforms were the two most important factors in consumers’ decision-making processes, as well as withTeng et al. (2018)’s work revealing a significant difference between heavy and light internet users in terms of online purchase intentions. This could be explained by the fact that tourists that spend much time browsing the internet are more experienced and used to exploring a variety of websites and social media platforms. Thus, ease of use and privacy do not matter as much to them as they do to less internet-experienced tourists.

Given the important role of hotel websites in customers’ purchase intentions, many studies have utilized web performance tools to measure hotel website performance. However, these studies did not provide guests’ preferences and their perceived importance of hotel website features. Thus, the current study provides an update on and further understanding of the perceived importance of hotel website features from guests’ perspectives.

The study also added value to the theory by analyzing the impact of three sociodemographic characteristics on the perceived importance of hotel website features, which may be useful for academics and researchers conducting further research into hotel website evaluation.

In terms of practical implications, this study provides an overall understanding to practitioners, marketers, hoteliers, and managers regarding the most relevant hotel website features from users’ perspectives.

As websites are intended for guests, it is important to examine what these guests expect from hotel websites. Therefore, this study demonstrates a need for hotel managers to prioritize improvement of specific website features that users with different age category and internet-use experience believe to be important.

Furthermore, this study may be useful for hotel website designers to analyse guests' habits and preferences which differ between younger to aged users and between more tech-savvy guests and less tech-savvy ones, in order to ensure that the hotel website will suit all requirements. These improvements could mediate the service gap between a hotel’s current website effectiveness and users’ expectations, thus minimizing the risk of losing hotel reservations to competitors.

6. CONCLUSIONS

The purpose of this study was to measure the relative importance of hotel website features based on users’ perceptions and analyse the impact of gender, age, and frequency of internet access on the importance given to each of the features. Ten features were tested: design, ease of use, privacy, corporate information, information on products and services, booking information and reservations, information on the surroundings, contact information, links to social media pages, and customers’ feedback options; and three hypotheses were proposed. For this research, a sample size of 406 tourists’ responses was used from the three main destinations in Morocco.

Among the ten hotel website features, four were found to be essential: information regarding the hotel’s products and services, booking information and reservations, ease of use, and contact information. Users also perceived privacy, design, and information on the surroundings as important features, while customer feedback options, corporate information, and links to social media pages were considered irrelevant.

Age and frequency of access of internet have a significant impact on the perceived importance of hotel website features, while gender does not have a significant effect. Future research suggests studying hotel mobile websites, as they represent a key source of information for smartphone users’ purchasing decisions.

This study has some limitations that provide interesting possibilities for future research. First, this study focused on Morocco. Thus, it would be interesting to carry out similar studies in other developing countries. Also, it would be interesting to make a comparison between domestic and international tourists. Additionally, it would be worth studying the case of hotel mobile websites, as they represent a key source of information for smartphone users’ purchasing decisions.