1. INTRODUCTION

Online reviews are a reality within social platforms for any business (Mazurek et al. 2020), especially for those that aim at increasing sales (Duan et al. 2008;Yang et al. 2017). In the hospitality business,Kim and Park (2017) highlight that social media review rating is a more significant predictor than traditional customer satisfaction for explaining hotel performance; andSchuckert et al. (2015) claim that for hotels and restaurants, the use of data mining in the analysis of reviews is crucial, even though most of these analysis ignore fake online reviews. We understand fake online reviews as non-authentic reviews writing by real (or not real) consumers/players on some platforms (Wu et al. 2020;Hu et al. 2011).

Many of investigations aim at discussing fake online reviews, highlighting the competition that exists within a specific industry, with an emphasis on rivalry, vendors, merchants and also on platforms in that industry (Luca and Zervas 2016;Lappas et al. 2016;Barbado et al. 2019;Martinez-Torres and Toral 2019;Hu et al. 2011;Goosling et at. 2018). However,Wu et al. (2020, pp. 2) point out that “few studies explore fake reviews by genuine consumers.” Hence, we can say that even though the phenomenon of fake reviews may not be new on a firm’s initiative point of view, it seems to be rather unexplored in what concerns the production of non-authentic writing by real consumers or someone who performs as a real consumer. Therefore, the current research focuses on fake online reviews written by genuine consumers that actually had the experience in a restaurant and by individuals who act as consumers without ever been in the restaurant they are reviewing.

Restaurants have been the subject of some researches within the hospitality industry (Luca and Zervas 2016;Lappas et al. 2016;Ahmad and Sun 2018).Wu et al. (2020) suggested a new line of research to be explored in future researches: the influence of countries’ culture on fake online reviews. This seems to be specially interesting to accommodate in Brazil where the phenomenon of social TV is a reality. This occurs when a TV viewer uses digital platforms to discuss, inform, share or assess TV contents (Chorianopoulos and Lekakos 2008;Proulx and Shepatin 2012). This phenomenon seems to be a Brazilian idiosyncrasy (in a cultural perspective) and some studies were conducted focusing on this reality, that has been studied under different perspectives in Brazil (Cruz 2016;Borges and Sigiliano 2016;Almeida 2020).

Thus, the research gap we will try to address with this paper connects (a)Wu et al. (2020)’s future research avenues related to countries’ culture, and (b) Social TV phenomenon as a mean to understand fake online reviews in restaurants. We aim at identifying types of consumers who have had (or not) a real experience as a diner. More specifically, we base on observations obtained in Brazil, to try to understand what makes someone that has never had the experience of eating in a restaurant assume he/she has the conditions to do the review; and what drives someone that has never had the experience of writing an online review to do so. These are conditions that in normal circumstances would be considered as necessary to entitle someone to perform a review. However, there is evidence that point out in a different direction and that is why disentangle this fact deserves further investigation.

Next section presents literature in Fake Online Reviews and offers propositions. The third section, Presence of TV and Brazilian Idiosyncrasies, discloses some cultural characteristics related to the power of TV in Brazil. The fourth section presents methodology and the empirical study. The results are presented in the section that follows, where statistical results and the four groups of customers that emerged from data analysis are put forward. In the Discussion section we present ‘The Online Restaurant Reviewer Matrix Types’ along with claims that can be withdrawn from this work. And finally, in the last section, we present theoretical findings, managerial implications and limitations and hits for further research.

2. FAKE ONLINE REVIEWS

The literature on fake online reviews, as well as the whole interest scholars have been putting on the reviews, is mostly focused on the relevance and impact these have in the business key performance indicators (Luca and Zervas 2016;Lappas et al. 2016) and not so much in the liability these can constitute, especially if treated as true by prospective buyers. Fake online reviews are created or arranged by consumers, online merchants, and also by review platforms (Wu et al. 2020).

Some studies offer reasons to create fake online reviews such asHu et al. (2011),Gossling et al. (2018),Lee et al. (2017) where explanations on why vendors, platforms and retailers often manipulate online reviews (Wu et al. 2020). What it is still unknown is why some individuals, with no agenda, embark on creating fake online reviews. To the best of our knowledge, there are no studies that attempt to unveil the understanding of the influential power of fake influencers in the restaurant industry and we believe this is likely to affect prospective and current client’s purchase ad recommendation intentions.Wu et al. (2020) highlighted the relevance of understanding (i) unethical acquisition of benefits from merchants, (ii) consumer unhealthy psychological needs, (iii) demographic factors, and (iv) different cultures affecting on fake online reviews. That said, the aim of this paper is to try to unveil the characteristics of these individuals highlightingWu et al. (2020)’s propositions related to the last point.

Table 1 resumes what the main findings of literature on the relevance of fake online reviews are, in the context of subjective norms that online reviewers establish. The findings were divided into five dimensions that assist in the understanding of the problematic (seeTable 1).

In the previous table, we resumed the main dimensions of analysis of the fake online reviews phenomenon. According toShen et al. (2015) and Chen andHuang (2013), online reviewers, are individuals that write texts on some platforms informing its experience as a consumer (or not, as we will see) in the service itself, and also in the media used to express the assessment and that are considered necessary for the review to be made. The reviewer needs to understand him/herself as self-efficient and understand the perceived usefulness of his/her behavior. The main disfunction of online reviews is that these may end up in fake information: assessments can be made without the real facts and, therefore, without being based on real experience (Malbon 2013;Mayzlin et al. 2014;Hunt 2015,Mukherjee et al. 2013;Ahmad and Sun 2018).

Both, the academic community (Wang et al. 2015;Lappas et al. 2016;Zhang et al. 2010) and the businesses world assume that reviews can influence consumer’s decisions in many different ways (Malbon 2013;Luca and Zervas, 2016). Working as referents, or as subjective norms, as stated by the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) (Fishbein and Ajzen, 1975), these individuals play a role in influencing consumer’s decisions. According to TRA model, this subjective norm has an influence on behavior that cannot be ignored, especially in this restaurant industry, in which the critic assessment plays a relevant and meaningful role (Oliveira and Casais 2019). Despite impossible to be ignored, these are out of the control of these firm’s managers most of the times. Hence, getting to know what this impact may be and investing in providing a good experience throughout the whole customer journey seems to be of capital importance.

Chatterjee (2001) highlighted that a negative online review has the power to negatively influence the perception of potential consumers and, therefore, to negatively influence the intention of purchase. In what concerns restaurants, research highlights the cultural and financial value generated by these reviews, thus assisting in the creation of an image (Zukin et al. 2015).Anderson and Magruder (2012) pointed out that an extra half-star on some platform, can lead a restaurant to sell almost 20% more. And even though this may help in understanding why players in some markets attempt at writing positive fake online reviews, that does not explain why individuals, that have never tried the service, feel like they should write a review. This has been observed in some circumstances, especially in Brazil, after watching TV programs dedicated to culinary and restaurants’ s assessment shows.

Even though it seems important to understand what type of individuals write fake online reviews, there is no research on attempting to understand the characteristics of these individuals. This would allow us to understand what motivates them to write without having a specific objective at hands. In fact, there seems to be a lack of knowledge concerning on the sources of this the behavior that can derive from (i) an inexistent experience of the individual as an effective user of the service; and (ii) an absence of previous experience in reviewing in a platform.Wu et al. (2020) coined the term “genuine consumers”, referring that these are poorly investigated on fake online reviews literature. So, there seems to be relevant to understand why real individuals do fake reviews. On the top of this understanding, it seems very important to understand the influences that some TV shows, like Social TV have on Brazilians. This TV show allows common people to have visual access to local restaurants that they would ever have the chance to try due to their economic condition, which is normally correlated with a low educational level. This seems to entitle these individuals to produce reviews (made by true profiles and not by machines, or by competitors or the restaurant itself) on platforms where they play the role of true consumers. Very often, however, these assessments have no comments and are just ratings, but still these ratings influence the overall assessment of the restaurant in a way that does not correspond to the reality. This fact deserves further attention.

These seems to be relevant elements that could assist in the attempt to understand why some reviews lack comments; and why there seems to be a mismatch between the proportion of the number of reviewers and the effective clients of a restaurant that is mentioned in a TV program. Hence, we would like to propose these as two main axes through which assessments are made in the restaurant business in Brazil, after the exhibition of a TV show. We would like to bring into the analysis the phenomenon of social TV as a relevant component of the environment in which this phenomenon takes place in Brazil. The specific context involves seven restaurants that participated in the Kitchen Nightmare TV show (the Brazilian version).

Among the many idiosyncrasies of Brazil, one concerns the way TV is present in the daily life of the common citizen. The strength of social TV seems to be a reality, along with the increase of gastronomy programs and the viral power of gifs, memes and videos of some of the main characters of Kitchen Nightmare. On the basis of this evidence, it was detected an increase in the number of reviews in the platform Google Reviews for the involved restaurants. Additionally, there is also evidence that some of this increased number of reviews may be the result of fake reviewers, that is: comments and assessments made by individuals that have never had the experience of eating in that particular restaurant and that end up by just rating the experience without any further comment that can prove that they were, indeed, there. Taking this into account, we would like to propose:

P1: there are reviewers that had the experience and reviewers that never had the experience of eating in the restaurant.

P2: there are reviewers that master the process of writing online reviews of a restaurant and others that have no experience whatsoever in producing online reviews in these platforms.

P3: some high context cultures like the Brazilian one stimulates individuals that have never had a gastronomic real experience in a restaurant, to feel entitled to produce a review upon watching a TV program related to this same restaurant.

Assessing a service without indeed having the experience of eating there may fall into what some researchers name as “herding behavior” or “mimetism” (Silva et al. 2018) and has in roots the idea that, if a small player does not have the means to have the experience itself, this player basis on the experience of a big player: someone who is more resourceful, and therefore had the chance of having the true experience. We can also observe this phenomenon in companies and understand it as “second-hand experience” (Silva et al. 2012). This mimetic behavior can also be understood as the “subjective norm” proposed in the already mentioned TRA (Fishbein and Ajzen 1980); and that claims that individuals beliefs and assessment of the potential outcome will influence the attitude toward the behavior, which, along with subjective norms and the motivation to comply, form the behavioral intention and the actual behavior.

Subjective norm is a construct brought by the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) (Ajzen 1985), an extension from TRA, where perceived behavioral control is also considered very important. Later, another extension of the original model was performed and originated an updated version of the Technology of Acceptance Model (TAM), in which subjective norm played the role of directly influencing the perceived usefulness and indirectly the intention to use and the usage behavior (Venkatesh and Davis 2000). This is also a construct that was used in the Health Belief Model (Janz and Becker 1984;Strecher and Rosenstock 1997) as an important factor in the behavioral changes required when in face of a certain health condition. Hence, it is, as we have seen, a very important construct, with the ability to influence behaviors that require a low self-efficacy level, as it seems to be the case of the production of a review in social media.

Considering that TV has a peculiar importance in Brazilian society (Hamburger 2011), there is room for this point to be further explored, along with fake reviews produced for restaurants, through social TV. This seems to be a singular phenomenon considering the importance that TV has in the routine of the medium class citizen in Brazil, possibly rooted in the anthropologic origins of Brazilian popular culture. Next section indicates some Brazilian idiosyncrasies related to the power of TV over this society.

3. THE PRESENCE OF TV AND BRAZILIAN IDIOSYNCRASIES

There are three characteristics of Brazilian context that should be taken into consideration: (a) television is a part of the Brazilian’s way of life (Hamburger 2005;2011); (b) Brazilians are connected to the Internet (Goldstein 2020) and (c) gastronomy has gained space in the entertainment industry (Monty 2018;Cruz, Monteiro and Ide 2019). Additionally, the country presents itself as the 7th most unequal in the world, according to the De Gini Index UNDP data for 2017 its educational average is below the world´s average, according to OECD; and, in this scenario TV plays an influential role in changing attitudes and behaviors (Rossi et al. 2010;Sá and Roig, 2016), especially in citizens with fewer alternatives of information. Telenovelas are the main cultural product of the country (Sá and Roig 2016) and often present a universe of luxury (Wajnman and Marinho 2006) that fills an aspirational market.

The concept of mimetism addressed bySilva et al (2018) seems to have a direct relationship with the concept of aspirational consumption in light of the influence of TV in Brazil and the fact that the term Gastronomy in this country often refers to luxury (Costa 2012). The search for an individual to be part of a group and report an experience that has not been lived can be a way for him/her to obtain the social status to which he/she is not a part of. And, in an online environment in which there is an overvaluation of a perfect world, the content of TV that is often approached in a luxurious way (Wajnman and Marinho 2006) can assert aspirational consumption, thus stimulating consumption simulation for peers (mainly in the restaurant industry in Brazil, due the association of the term Gastronomy with luxury).

Adding to this context, the social TV phenomenon helps to empower the viewer that feels the right to judge everything: what he/she knows of and what he/she knows little about of. This goes in lie with the well known paradox of “Dunning-Krueger Effect”. By knowing it or not, having the real experience hands-on or not, criticism is built on any content. This trend is part of the “know-it-all generation” (Stein 2013), in which it seems unacceptable to millennials’ peers’ eyes to admit that there may be a subject that an individual has no opinion about. Apparently, what everyone expects is that an opinion about every single subject exists and that can be expressed through social media.

There are also two other components claimed byRoberto Da Matta (1981), one of the main Brazilian anthropologists, and that corroborates the idiosyncrasies in the country. Some of these include personalism in relationships, which indicate that relationships are mediated by the value that ‘person A’ attributes to ‘person B’. Another characteristic concerns the existence and positive assessment of the trickster, which is another feature of Brazilian culture - the individual who causes harm to others in order to have a personal benefit is normally praised by the society. Additionally, the Brazilian is an individual who tends to value people more than the rules, laws and norms giving space to the so-called ‘Brazilian way’ (Prestes-Motta and Alcadipani 1999).

A Brazilian version of the reality show “Ramsay’s Kitchen Nightmares” highlights these peculiarities in Brazil. This uniqueness can generate different feelings in the viewer, such as empathy, sadness for the closing of the restaurant, and anger of characters of an episode. This can motivate online restaurant reviews based on an experience as a viewer and really not as a diner. Unthinkable in other cultures, this is an evident reality in Brazil.

4. METHODS

Data was collected from Google Reviews platform, which has, in Brazil, more reviews than Tripadvisor. Between 08/27/2019 and 03/30/2020 2,547 reviews were collected for seven projects: El Maktub (193), Antigo Bar (135), Joka's Grill (200), Alquimia (237), Barwarchi (298), Pé de Fava (999) and Hero's Burger (487). The following variables were assessed:

Evaluation Score (each evaluator assigned a score from 1 to 5 in their evaluations for each restaurant);

Local Guide (information from a collaborating Google user who reports experiences on different locations and establishments (this local guide badge is obtained by the user after evaluating at least 25 establishments). In order to identify whether the comment was based on a real experience or on the basis of the Social TV phenomenon, the figure of the local guide was considered. Here we assumed a dummy variable of 1, if the person as a local guide; and 0, if not);

Real Experience (when considering the 2,547 reviews on Google Reviews, it was possible to identify the reviews that were real through the interpretation of comments, photos and in-depth descriptions; thus, here we also assumed a dummy with 1, if a real experience was recognized, and 0, if not);

Number of Reviewer Ratings on Google Review (each local guide out of 838 from the 2,547 reviews analyzed had a history of the number of reviews performed after becoming a local guide; this variable was used and considered as discrete).

A clustering process was developed in three distinct stages:

Calculation of the dissimilarity matrix for categorical and continuous variables viaGower's metric (1971);

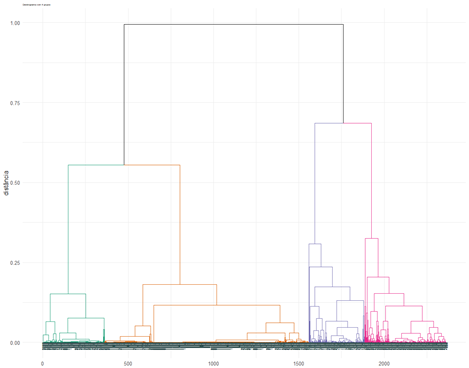

choice of the clustering method - the hierarchical method was used to group objects in clusters based on their similarity. This algorithm treats each appraiser as a cluster. Then, pairs of clusters are merged successively until all clusters have been joined into a large cluster containing all observations. The similarity (or distance) between each of the clusters is calculated and the two most similar clusters are merged into one. The result is a representation based on a country tree, called a dendrogram (Figure 2);

cluster evaluation (determining the number of groups and interpreting each group) - the possibility of 4 groups was previously considered here and this decision was subjective and an algorithm using R software was used to identify the number of groups.

Spearman's Correlation Analysis was used to check correlations between the resulting groups and the variables (i) Evaluation Score and (iv) Number of Evaluator Evaluations on Google Review (p ≤ 0.1). Analysis of Variance was used to measure the impact of the groups identified in the Cluster Analysis in the evaluation score (from 1 to 5 stars). As data was not parametric, the Kruskal-Wallis Test (p ≤ 0.1) was used.

5. RESULTS

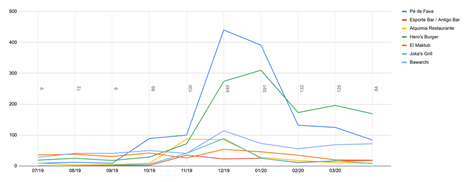

1609 (63.12%) assessments in this survey, out of the 2547 total assessments, were found not to be real. There is no possibility of stating that these 1609 assessments were carried out only from the Social TV phenomenon. According toFigure 1 there was an increase in assessments for establishments as of September 2019 (when the second season started), which contributes for confirming P1.

Figure 2 is a dendrogram showing how these 2,547 observations came together. Axis X (number of observations) represents the 2,547 reviewers and axis Y is a metric scale e varying from 0 to 1 that measures the distance between the reviewers. Specifically, in relation to the distance between these, an algorithm was used to measure the distance (similarity or dissimilarity among them. For example, if observations 13 and 50 have the same profile in the variables (a) local guide, (b) Real / Social TV Experience and (c) Project Evaluation Note, these observations (13 and 50) are grouped together forming a new element that will be added to another observation with similar values for the three variables simultaneously.

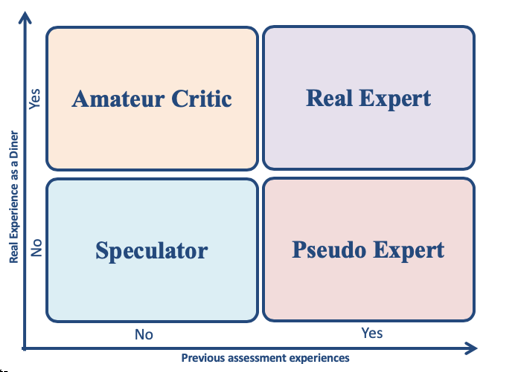

Table 2 resumes the results of the Cluster Analysis, according to which we named the resulting four groups as Real Expert, Speculator, Amateur Critic and Pseudo Expert. In these groups there was a perfect discrimination of the four categories; that is, these combinations were natural, emerged from the data and were not normative. For example, the discrimination between having had real experience and not having any experience was 100%. Thus, P3 is confirmed due statical results presented four groups.

6. DISCUSSION: ONLINE RESTAURANT REVIEWER TYPES MATRIX

The perfect discrimination between the groups was essential for these to be plotted in the proposed framework: the vertical axis considers real consumption experience in one of the restaurants; and, on the horizontal axis, that reviewer may or may not have had previous assessment experiences on Google Reviews. This result was obtained through the Cluster Analysis that puts forward a contribution not discussed in the literature on Fake Online Reviews: the evaluation written by a real individual who had no consumption experience, but that evaluates the consumption experience.

Lappas et al. (2016),Malbon (2013) andHunt (2015),Ahmad and Sun (2018) andHu et al. (2011) analyzed the impact of fake online reviews on the industry. However, the results of this investigation go on to show that in addition to machines, competitors and real consumers, real individuals who are not consumers and who write reviews on platforms should be considered in the analysis as well.Figure 3 depicts the Online Restaurant Reviewer Types Matrix.

The Real Expert is one who has had a real experience in the restaurant and also has previous assessment experiences; the Speculator is one who has not been to the restaurant and also has no previous assessment experience, but who has nevertheless written a review; the Amateur Critic is one who has no history of previous assessments, but has been on site; and the Pseudo Expert the one who made comments about a restaurant without having a consumption experience, but having previous experiences as a reviewer.

The ‘Real Expert’ is a local guide who has a history of evaluating other establishments and his/her judgment is built on a real experience. He/she is, therefore, more reliable when compared to the ‘Speculator’ and ‘Pseudo Expert’ groups. The Amateur Critic has also had experience as a diner, but he is not a local guide; he might be more demanding due to (i) being a more careful and demanding consumer; (ii) having a great previous expectation in relation to the restaurant because he/she watched the Nightmare in the Kitchen or because the restaurant received referrals from friends; or (iii) because a previous research of the ratings of the restaurants on the platforms allows him/her to take its excellency for granted. Thus, P1 is confirmed here, assuming that the two groups had real experience and that other two did not have. The two groups performed as reviewers.

If the groups ‘Real Expert’ and ‘Amateur Critic’ can bring valuable feedback to a restaurant, the Speculator and Pseudo Expert groups can bring problems regarding their statements in the online environment. Although in this study the referrals were positive (close to 4 on average), the content of their reviews (because they are not based on a real experience) can reveal a fantastic experience and that can influence fears and frustrations of prospective customers.

The Online Restaurant Reviewer Types Matrix highlights a relevant issue that we labeled as ‘real people that are not indeed consumers’ – these are, according to the proposal, the Speculators and the Pseudo Experts. Hence, we take a step further the claim ofWu et al. (2020) of the relevance of spending time investigating genuine consumers producing fake reviews. We go an extra mile and highlight the existence of ‘non-genuine consumers’. These are not consumers, and not even machines/robots producing texts. These are not competitors, retailers or vendors. These are, as a matter of fact, real individuals performing revisions on the basis of a non-real experience and acting as genuine consumers.

The Speculator, who is neither a diner, nor a local guide, is the one who had the lowest average in the assessment between the four groups. This profile can only have the objective of evaluating as a strategy to feel part of a group of people, reinforcing the concept of subjective norms and the idealization of the Brazilian, as referred above: the cultural characteristics discussed byDa Matta (1981) - especially personalism (“I review, therefore, I am part of this group”).

The Pseudo Expert may have the intention to write a typical review of a trickster – character discussed byDa Matta (1981). In fact, he/she is a local guide and as such he/she can receive gifts from Google, invitations to participate in events, or access to new products before they are placed on the market. Pseudo Expert's comments can be made just to get a score and obtain these possible benefits from Google, or also to feel indeed part of a group. Hence, it emphasizes the idea of the trickster in light ofDa Matta (1981) 's anthropological analysis.

7. CONCLUSIONS

The evaluation of a restaurant in the online environment, without any content, seems to be not relevant. However, it impacts the restaurant’s image and influence in client’s willingness to purchase the service. The initial purpose of this investigation was to characterize the online reviewers of restaurants in Brazil from the perspective of the Social TV phenomenon. We found that the peculiarities related to the presence of television in these people’s everyday life, influenced the construction of fake online reviews for restaurants that participated in a television program. For a better understanding of these consumers, we plotted the Online Restaurant Reviewer Types Matrix. The Brazilian context studied in this research seems to be singular in the restaurant industry. More research in other industries may be necessary. However, we believe to have been able to confirmWu et al. (2020)’s proposition related to countries’ culture impact on fake online reviews.

These results validate that we are actually facing an empowerment tool to both, the viewer and the consumer. It empowers the viewer (non-genuine consumer) from the moment he/she can virtually influence others (Speculator and Pseudo Expert). At the same time, it empowers the genuine consumer (Amateur Critic and Real Expert) as he/she recounts his/her experience as a diner, which somehow extends their aspirations and intended behavior to an actual behavior. Results also stress that fake online reviews are not so much written by competitors, retailers or vendors; or by the company itself or even by third parties hired to write positive reviews. This is what many authors have been discussed before (Hu et al. 2011;Goosling et al. 2018;Lee et al. 2017;Wu et al. 2020). Our research pointed out the existent of other relevant profiles of fake online reviews’ writers. The Speculator and the Pseudo Expert groups act as genuine consumers and produce reviews as if they had actually visited the restaurant, whereas the closest experience to that they have had was, as a matter of fact, watching a TV show - where that was experienced by someone else. The dystonic approach conveyed here seems to be accepted in some cultural groups, normally more misinformed, less refined and with small to none access to the real experience of eating out in such restaurants. These results in Brazilian culture can be analyzed from three perspectives:

the reviewer’s effort to be recognized and distinguished from others – in the sense of social distinction from the status discussed byBourdieu (1979). The term Gastronomy in Brazil often refers to luxury (Costa 2012). Assessing a restaurant which was part of a TV program can be a way of achieving this desired reviewer position and being recognized by others. The Brazilian television escapes from the reality of most of the population by exhibiting luxurious scenarios (Wajnman and Marino 2006) that most people have no access to. These people, working as individuals that review a restaurant (that participated in a reality show), can have access to that aspirational (luxurious) universe that was, up to them, kept away from them.

being a trickster - in the sense that the individual can get some kind of benefit from others and/or eventually have the power to harm others (in this case a restaurant). The Pseudo Expert group can be explained using this feature of Brazilian culture, since the reviewer can get Google benefits when becoming a local guide and exert power by influencing a restaurant reputation.

enhancing the traces of personalism in relations, in the sense presented byDa Matta (1981) - this trait in Speculators group can be explained from the moment a viewer manifests empathy with employees and owners of a restaurant, judging them on the basis of his/her experience as a viewer and not as a diner. The relationship of warmth/affection/empathy created by the viewer empowers him/her to review the restaurant like a diner.

Theoretical Implications

We have extended the research on fake online reviews on the basis of a real-life experience in Brazil. The idiosyncrasies related to TV in Brazil corroborate the theoretical assumption that links national culture to the likelihood of individuals to feel entitled to produce fake online reviews. This is conveyed in P3 of our study. These results have some theoretical implications in the literature related to the theme. These are: (i) the presentation of the term '‘real people that are not indeed consumers’ or (‘non-genuine consumers') and the attempt of these individuals to feel entitled to produce online reviews as if they were real consumers; (ii) not only ‘genuine consumers’ are poorly studied, as ‘non-genuine consumers’ have not been discussed before within the field of fake online review’s literature; and, (iii) there seems to exist evidence that the Speculator and Pseudo Expert types of consumers can be considered as 'non-genuine consumers' when they publish fake online reviews (and they did not have a real consumer experience) (P2). These theoretical implications highlight the importance of this investigation not only for the restaurant sector and the hospitality industry, but also for the role the ‘non-genuine consumers’ may have in review’s creation.

Managerial Findings

The main managerial implication for the hospitality industry has to do with the relevance of monitoring the online reviews, for further action, namely asking the platforms to remove the fake reviews, or, at least, to be able to confirm these before these go public Similarly, understanding the comments of Real Expert and Amateur Critic groups is an important feedback mechanism to keep trusting what the evaluators praise and to solve the problems reported in written frustrations. This also shades light for the relevance of strategically considering if a participation on a TV show like this pays off, because its drawbacks may – by far – surpass possible benefits.

Limitations and Future Research Avenues

Some propositions presented byWu et al. (2020) could not be checked here such as demographic factors impacting fake online reviews. It was not possible to have these information (e.g. gender, income and educational level) because some nicknames on the Internet cannot be understood. Other limitation in this investigation is the generalization of results– we cannot claim that these results explain all Brazilian consumers (it is only for the viewers of those restaurants showed on the Ramsay’s Kitchen Nightmares TV show.

However, this research is relevant and highlights some future research avenues. The first of them is to understand motivations to be a non-genuine consumer writing fake online reviews: why does some individual want to perform as genuine consumer writing fake online reviews? Adding to this perspective, we can check the influence of countries on non-genuine consumers: is there difference among genuine consumers and non-genuine consumers related to motivations to write fake online reviews in Brazil compared to other Latin America countries or Portugal? These results also demand reflection on ethics: why reviewing a restaurant without having had a real experience?

Wu et al. (2020) demonstrated that some consumers (unethically) try to acquire benefits from merchants. This research presented Pseudo Experts as non-genuine consumers. But, are the Pseudo Experts non-consumers who try to gain benefits from platforms writing, indeed, fake online reviews? These would be difficult to know. Future researches may seek to understand the incentives of Speculator and Pseudo Expert reviewers to write reviews without being real diners. Understanding the characteristics and motivations of online reviewers is very important. Yet, this is little explored in the hospitality industry.