INTRODUCTION

Academic literature has emphasised that self-imposed barriers rather than workplace barriers are the most significant obstacles to women's advancement in the hospitality industry. The "glass ceiling" paradigm is now virtual, and other factors enable women's progression in the sector (Boone et al. 2013). Initiatives such as mentoring, executive education, leadership training, and providing women with relevant assignments, among other measures, may contribute to overcoming workplace barriers (Knutson and Schmidgall 1999). Despite advancements in the last decade by hospitality organisations in this direction, there is still a long road ahead for women's progress in the industry (Woods and Viehland 2000;Fleming 2015).

This study analyses women's access to the culinary profession and obstacles regarding their progress in the field as they work towards a chef's status. Its basis is an international survey carried out during 2010–2016.

Our basic research question is about the role that entrepreneurial attitude plays in women’s access to the position and promotion of chef. Furthermore, our study investigates whether this role is moderated by other factors, such as training, mentoring, or the workplace environment.

The research was based on a survey carried out among an international community of haute cuisine cooks, chefs, and senior culinary students.

This research concludes that entrepreneurial attitudes are crucial to women’s promotion, particularly when combined with mentoring and the development of specific workplace skills. These elements allow women to overcome barriers and lower their perception of hostile environments in haute cuisine kitchens.

1. THEORETICAL CONTEXT

Women's access to hospitality management positions has received attention within hospitality literature. Despite women's representation in the hospitality workforce, their place is not reflected in their roles in either management or education (Baum 2013;Figueroa et al. 2015;Pritchard and Morgan 2017). However, the hospitality sector is highly relevant to women's employment and entrepreneurship opportunities (Morgan and Pritchard 2019), and it is a challenge for women in developing countries (Stefanović and Dimitrijević 2006).

A recent publication has reviewed the literature on gender discrimination in haute cuisine (Albors-Garrigos et al. 2020). One conclusion was the scarcity of literature discussing the enablers for female cooks to be promoted. This article aims to examine those elements and, more specifically, the role of entrepreneurial attitudes that seem critical for female chefs in overcoming the barriers of the glass ceiling in haute cuisine.

1.1. Haute cuisine and gender discrimination

How could we define the context of the study? A classical and concise definition of haute cuisine is the "type of cuisine that marks the status of the consumers and the identity of those who cook and serve and the expertise that makes the cooks masters of hauteness" (Trubek 2000, 201).

Why are we carrying out this study? Haute cuisine is an essential subsector of hospitality that is crucial to tourist economies. The Michelin guide, a paradigm of haute cuisine, selected 16,060 restaurants worldwide, of which 3,362 were classified as Bib Gourmand or a restaurant that serves quality food at a good value, "[with] the ability to order two courses and a glass of wine (or dessert) for $40 or less." 12,100 of these total restaurants were classified as Michelin Plates, meaning that they have neither a star nor a Bib Gourmand (Michelin Guide 2021). Finally, the Michelin Guide used a rating system of Michelin “stars” to grade restaurants on their quality. Across the world, there are a total of 2,817 Michelin star restaurants. This is broken down into 2,290 restaurants with one Michelin star, 414 restaurants with two Michelin stars, and 113 restaurants with three Michelin stars (Michelin Guide 2021). Furthermore, there is a recognised relationship between gastronomy and tourism (Millán Vázquez de la Torre et al. 2016).

Gender discrimination in this sector is highlighted by the literature on hospitality. Male values are predominant due to the military origin of professional cooking (Cooper et al. 2016). It must be emphasised that cooking is a gendered task. Thus, there are differences for males and females when they cook in the domestic or public spheres (Jonsson et al. 2008;Hermelin et al. 2017). This disparity is an interpretation of the social and sexual division of labour, according toSwinbank (2002). In almost all cultures, cooking is a female task in the household (Swinbank 2002). We will discuss various barriers and enablers that women face in their professional careers in the field later in the article.

1.2. Entrepreneurial attitude, and female chefs' advancement

1.2.1. Entrepreneurship and gender. Female entrepreneurial intentions

Although recent studies have emphasised the importance of gender in entrepreneurship, primarily in services (Elam et al. 2019) and its role in social sustainability and regional development (TFSN 2019), we believe it has not been properly addressed.

There has been inevitable controversy in the literature on whether women's entrepreneurial choices are defined by their competencies and motives or are predefined by their socio-economic context. Research confirms a trend in the former direction (Nina-Pazarzi and Giannacourou 2005;Kakouris 2016).

Academic literature accentuates how entrepreneurial intentions rely on personal attitudes and the contextual environment, where the former moderates individual competencies, social perception, and psychological characteristics (Anggadwita and Dhewanto 2016). In regard to female entrepreneurship,Noguera et al. (2013) emphasised that the main influencing factors were the perceived capabilities (with a positive effect) and the fear of failure (with a negative impact). On the other hand,BarNir et al. (2011) corroborated the relevance of role models in promoting female entrepreneurship. Furthermore, these role models indirectly affect the entrepreneurial capabilities' perception of entrepreneurial self-efficacy. Media analysis has substantiated this in haute cuisine since famous female entrepreneurs' media exposure positively impacts aspiring women in pursuing a chef's career (Albors-Garrigos et al. 2020). Celebrity chefs, as well as role models, have had an influence on this phenomenon (Madichie 2013).

An enabling aspect of the female approach to entrepreneurship is that it is characterised by building contextual embeddedness and then venture creation in a masculine environment (Aggestam and Wigren-Kristoferson 2017).

1.2.2. Female entrepreneurship in the hospitality and restaurant industry

A study on the GEM data byRamos-Rodríguez et al. (2012) identified three variables influencing the entrepreneurial decision in the hospitality and restaurant field: age (young), gender (female), and household income (medium-high). Moderating factors found were personality traits, self-confidence, and experience.

As is the case with many creative professions, the entrepreneurial path forms part of the chefs' career (Balazs 2002). Yet, when female chefs open their restaurants, they face financial constraints (Harris and Giuffre 2015). Successful female chefs who were willing to open restaurants have collaborated with famous chefs, received awards, or been featured in the media (Harris and Giuffre 2015). Through restaurant ownership and management, entrepreneurship is recognised as beneficial for chefs, particularly women (Anderson 2008). This approach allows more flexibility in balancing work and family commitments, which is a challenge for many individuals with paying jobs (Bartholomew and Garey 1996). Some biographies such asGabrielle Hamilton (2011), as well as field research (Cooper 1998) enlighten many women's obvious entrepreneurial path to haute cuisine.

Female entrepreneurial haute cuisine can also increase women’s presence in the culinary industry by questioning the prevailing culture and business models, which are so far successfully and widely spread by famous male chefs (Harrington and Herzog 2007).

Severalqualitative studies analyse entrepreneurship as a vital enabler offering women the possibility of starting a restaurant and enhancing their position (Cooper 1998;Anderson 2008;Madichie 2013;Aggestam and Wigren-Kristoferson 2017).Druckman (2012) andHarris and Giuffre (2015) outline this role in their monographs on female chefs. Other authors (Albors-Garrigos et al. 2019) consider the entrepreneurial activity to be a critical enabler based on quantitative analysis.

1.3. Chef's career satisfaction and expectations

What elements define the expectations of chefs in general and female chefs more specifically regarding their professional career? How can they measure their level of female professional advancement?

Zopiatis et al. (2018) suggest that extrinsic motivation plays a significant role in female chefs' career advancement, increasing their visibility and promoting their skills through public media (Druckman 2010;Harris and Giuffre 2015). Other agents in the field contribute generously to this dissemination, including the James Beard Foundation, Women Chefs and Restaurateurs (WCR), Les Dames d'Escoffier (Hartke 2018), and the Women Chefs of Kentucky Initiative, which sponsors mentorship opportunities for female chefs in Kentucky (Weaver 2018). Their role is decisive within most advanced gender cultures such as the United States, which has the best female chef awards (Childers and Kryza 2015).Zopiatis and Melanthiou (2019) have published extensive research on this topic, supporting the idea that it contributes to breaking the glass ceiling for women's progression in professional kitchens.

Some academics have pointed out that obtaining Michelin stars means worldwide recognition (Lane 2011;Vincent 2016). For female chefs who face difficulties in achieving stars, public media (i.e., journals, television, Internet) becomes a crucial factor in becoming visible (Druckman 2010).

At the intrinsic level, men and women promote themselves in different ways. Women must create status and prove expertise (Eagly and Carli 2007;Zhong and Couch 2007). However, opening a restaurant is the most common alternative (Heilman and Haynes 2005;Haddaji et al. 2017a).

1.4. Moderating factors

Are there moderating factors that influence the entrepreneurship drive towards female careers in haute cuisine?

1.4.1. Workplace environment

What are the characteristics of a professional kitchen? The environment of restaurant kitchens is harsh and arduous, notably in Michelin-starred restaurants. Additionally, professional kitchens are somewhat competitive and challenging (Fine 2008). The working conditions are demanding, as kitchens are usually hot, dirty, and tiny. In contrast with the high level of work and dedication required, wages are low and chefs are poorly paid (Pratten 2003b;Leschziner 2015). Cooks and chefs need a significant amount of resilience and determination to endure the job (Tongchaiprasit and Ariyabuddhiphongs 2016). Due to their domestic and nurturing roles, women are generally excluded from the kitchen socialisation sphere (Bourdain 2013, 158).

Moreover, as recent studies have confirmed, Michelin-starred chefs make up a solid occupational community with a distinctive occupational culture. Those conclusions suggest that identity and culture are interrelated because the cultural components of the Michelin chef’s occupational culture operate to reinforce a sense of identity among its members (Cooper et al. 2016).

Gordon Ramsay stated that "a kitchen has to be an assertive, boisterous, aggressive environment, or nothing happens" (Pratten 2003a). This statement confirms the authoritarian haute cuisine management style (Pratten 2003a;Cooper et al. 2016). Working hours are also long, irregular, and unsocial (Jonsson et al. 2008). A high level of work discipline is essential to advance in the profession (Pratten 2003a). Fear is an important component of the haute cuisine climate, asGill and Burrow (2017) discovered. Banter and intimidation are deeply rooted in the partie system and chef community, and they are not always well differentiated (Cooper et al. 2016;Giousmpasoglou et al. 2017). These practices clearly affect female candidates in their promotion on the chef’s ladder. Furthermore, fear promotes conformity and avoids questioning of the status quo, thus supporting the authoritarian management style of the industry.

But how does this environment affect gender discrimination in haute cuisine? The gender preconception discussed above, and the professional kitchen's adverse environmentare the leading causes of the low number of female cooks and chefs. The kitchen workplace is built on a masculine ideal (Druckman 2010).

1.4.2. Skills needed and learned at the workplace

In view of the previous mentioned authoritarian styles, there is a need for proper kitchen management. A model of chefs as transformational leaders has been proposed capable to improve kitchen organisational culture. This pattern sustains food production success (Mac Con Iomaire et al. 2021). This model is well adapted to female chefs’ leadership as various examples illustrate (Williams 2019).

For food supervisors in a high-quality restaurant, the scholastic literature outlines the significance of on-the-job involvement instead of formal instruction, as well as the critical requirement of sound food knowledge and a high level of aptitude and inspiration (Allen and Mac Con Iomaire 2016,2017).

Zopiatis (2010) investigated the skills that contribute to the achievement of a top chef position. He found that high cuisine needed individuals with various skills, the most important being technical competencies (culinary-specific), followed by management competencies (Pratten 2003a,2003b). Thus, a chef must be both a culinary artisan and an active business manager, and the skills required to be a head chef differ from those needed to be a simple cook (Pratten 2003a,2003b).

In contrast with other studies that linked cuisine innovation to job commitment and satisfaction,Ko (2012) found that technical skills were minimally important. From an individualistic point of view,Carvalho et al. (2014) emphasised effort, hard work, dedication, love, education, and intrinsic features such as competence and talent.

Workplace learning and training are crucial in hospitality (Vujic et al. 2008) and is particularly significant for becoming a chef (Haddaji et al. 2017b). It is also essential for chefs to combine different formal and informal learning strategies through traditional academic and professional training courses. Nevertheless, informal learning through experience, learning from others, receiving feedback from managers and supervisors, participating in competitions, and "trial and error" are all complementary assets (Cormier-MacBurnie et al. 2015). It is also crucial to assume responsibilities, take the initiative, and develop confidence (Haddaji et al. 2017b). Finally, business acumen is critical in the career of a chef. Participants who have a restaurant or are willing to open one counted on their own skills, recognition, and sound business and financial resources (Haddaji et al. 2017b).

Chefs show patience and consistency and are confident of the best way to accomplish their goals; they pay attention to every detail. They have an intuitive, experiential, and complete view of the kitchen and are geared toward execution. Their success is a continuous process of learning. Both technical and management skills are essential (Dornenburg and Page 2003;O'Brien 2010).

AccordingtoHarris and Giuffre (2015), female chefs are "encouraged to lean in at work and to find ways to fit within current occupational arrangements" (p. 91). They must also demonstrate their physical and mental strength by adhering to workplace work rules and culture such as "working long hours," "refusing help," "learning to avoid any forms of feminine emotional displays," and proving that "they will not be disruptive to the masculine culture" (p. 129).

However, can female chefs demonstrate special skills in the kitchen field? A study of female chefs in Israel demonstrated how the women’s femininity benefited their cooking, staff, and restaurants and granted them certain privileges, such as professional flexibility to establish spaces that operate under different rules and redefine the nature of good dining. These chefs claimed that their leadership style based on empathy and compassion allowed them to inspire a fresh and efficient management style (Gvion and Leedon 2019).

1.4.3. Barriers to female chefs' progression

Women cooks face multiple obstacles in haute cuisine and endure a lot of pressure balancing work and family, which gets even more demanding in Michelin-starred restaurants (Bartholomew and Garey 1996;O'Brien 2010;Haddaji et al. 2017b). Certain external obstacles in kitchen work are due to the general understanding of feminine characteristics (Druckman 2010). The workplace environment and masculine culture also condition gender discrimination (Bourdain 2013), which we discussed previously.

Household duties determine the participation of female chefs in the job because they take their personal and professional decisions into account (Bartholomew and Garey 1996;Harris and Giuffre 2010). Sociologists (Glauber 2011) argue that versatility for job inclusion is accomplished more easily in mixed gender work settings. Thus, an increased presence of women in restaurant kitchens will build more flexible schedules for the job. Their partners' assistance acts as a facilitator, but family obligations are still an obstacle (Carvalho et al. 2014).

Eventually, the conventional understanding and distribution of family responsibilities should be questioned to achieve an equal allocation of household duties, a better work-life balance, and, ultimately, a "happier community" (Harris and Giuffre 2015, 129). For the same reason, social policies should be adapted to promote more women in the workforce and to help both men and women cope with the demands of their personal and professional lives (Harris and Giuffre 2015).

In relation to the perception of these barriersBoone et al. (2013) carried out a study among 100 high-level male and female professionals in the hospitality field (cruising, gaming, hotels, and restaurants). When asked about their perception of the barriers for women’s advancement in their career, a similar percentage of women and men answered that family responsibilities, work-life balance, and a lack of confidence were all self-imposed, in the sense that they arise through personal choice or priorities. On the other hand, the following were considered workplace-imposed barriers: gender prejudices or negative attitudes rendering discrimination, organisational forces not facilitating female inclusion, and lack of mentoring.

1.4.4. The role of mentoring

The lack of mentoring has been mentioned as a barrier in hospitality, and its presence in the haute cuisine context is essential and decisive for women to advance in the restaurant workplace hierarchy (Harris and Giuffre 2015). In male-led professions such as haute cuisine, mentoring may be an enabler (Martin and Bernard 2013). Mentoring is signalled as a critical factor in job satisfaction for hospitality chefs (Abdullah et al. 2009). Female chefs could challenge the "gender dynamic of the gastronomic field" by mentoring other female chefs or cooks (Harris and Giuffre 2015, 199).

Mentors could also play a significant role in facing gender inequality by presenting mentees with new contacts from inside and outside of the workplace (Harris and Giuffre 2015). They can also share the informal work culture, such as norms, roles, and relationships, and facilitate their access to exclusive or restricted networks (Harris and Giuffre 2015, 199).

A successful mentorship helps to define priorities and strategies for reaching goals in the long term. Mentors should also indicate a strong interest in their mentees' futures, motivating them and indicating opportunities (Knutson and Schmidgall 1999). However, female chefs favour female mentoring, and their absence may be a possible obstacle to success (Harris and Giuffre, 2015;Remington and Kitterlin-Lynch 2018).Dashper (2019) has pointed out how mentoring supports women in focusing their hospitality career on management leadership.

Ultimately, mentoring does not contribute to women's advancement unless further accountability is taken in conjunction with career opportunities (Ibarra et al. 2010). Mentors, corporate power, and funding are essential if thereis a clear intention to move forward. Sponsorshipis more compelling than mentorship for women when there is competition for promotion (Ibarra et al. 2010).Mac Con Iomaire (2008) reflects on the role of mentoring in fostering culinary talent and finds that it is an underresearched area given its significance.

2. METHOD

2.1. Respondents

We based this study on a survey collected online from 202 cooks, chefs, and senior culinary students that are members of the Association of Maîtres Cuisiniers (France), the Basque Culinary Centre (Spain), and the International Association of Culinary Professionals (USA). The respondents were 58% men and 42% women of different ages and at different stages in their professional careers. The survey was first pretested with personal interviews to check that the language was clear and well interpreted in English, French, and Spanish. A group discussion was carried out previously with ten female cooks and chefs to discuss relevant issues. The sample composition is shown inTable 1.

We avoided common method bias, assuring respondents of their anonymity and that the data would be analysed at an aggregate level for research purposes (Chang et al. 2010). The sample response rate of 55.7% was assessed. A test for non-response bias with 20 individuals showed no significant differences between responding and nonresponding individuals about their age, gender, origin, professional degree, etc. (Sax et al. 2003). We followedPodsakoff et al.’s (2003) recommendations for common method variance by revising the questionnaire design and being cautious of formative constructs, as will be discussed.

2.2. Materials

We designed an online questionnaire consisting of 90 questions with Likert responses on a scale of 1 to 5. It included the following blocks of questions:

General information on the respondent, such as information about gender, age, profession, and nationality.

Career expectations include obtaining Michelin stars, becoming a celebrity chef with media recognition, and owning their restaurant.

Entrepreneurial initiative: for those respondents who had an entrepreneurial objective, their aims and how they built their career accordingly.

Barriers and facilitators: different factors that harden the learning process and evolution inside the kitchens such as work-life balance, renouncing their social life, or travelling.

Mentoring and leadership: access to a mentor during their apprenticeship, their mentor's gender, the prevailing leadership style in the kitchen, and the style used by survey participants.

Skills learned at the workplace, such as knowledge, skills, and attitudes, facilitated integration inside the kitchen, and the professional work environment.

If the workplaceenvironment is challenging, stressful, tight, smooth, collaborative, competitive, flexible, hierarchical, challenging, and/or encouraging.

Skills needed at the workplace, such as those needed to succeed and to evolve as a chef.

The following variables inTable 2 became significant in the research.

| Variable | Questions | References |

| Career expectations | To obtain Michelin stars; to be more present in communication media; to have a restaurant. | Bartholomew and Garey 1996;Heilman and Haynes 2005;Eagly and Carli 2007;Zhong and Couch 2007;Druckman 2010;Childers and Kryza 2015;Harris and Giuffre 2015;Haddaji et al. 2017a |

| Entrepreneurial attitude |

Why did you plan your start-up business? To be my own chef; to advance my career; to make more money; to have a better work-life balance; to develop my restaurant. How relevant are the following elements in the project: to be visible in media; to have public recognition; to have a good team working in the restaurant? | Bartholomew and Garey 1996;Balazs 2002;Anderson 2008;Druckman 2010,2012;Madichie 2013;Harris and Giuffre 2015;Aggestam and Wigren- Kristoferson 2017;Haddaji et al. 2017a;Albors-Garrigos et al. 2019 |

| Perception of barriers |

What do you sacrifice for your career? Family; entertaining; travelling; friends. | Bartholomew and Garey 1996;Druckman 2010;Harris and Giuffre 2010;O’Brien 2010;Glauber 2011;Boone et al. 2013;Carvalho et al. 2014;Haddaji et al. 2017b |

| Workplace environment | How would you describe the kitchen environment? Hard and difficult; competitive; highly hierarchical; challenging; masculine. | Ortner 1974;Pratten 2003a,2003b;Fine 2008;Jonsson et al. 2008;Druckman 2010;Bourdain 2013;Leschziner 2015;Tongchaiprasit and Ariyabuddhiphongs, 2016;Brunat 2017 |

| Skills learned at the workplace |

How has your work environment contributed to your professional development? To take diverse responsibilities; to take more initiative; to challenge me and to have more confidence; to develop my skills of innovation; to develop my communication skills; to develop my management and negotiation skills; to have more professional contacts. | Dornenburg and Page 2003;Pratten 2003a,2003b;O'Brien 2010;Zopiatis 2010;Ko 2012;Carvalho et al. 2014;Cormier-MacBurnie et al. 2015;Harris and Giuffre 2015;Allen and Mac Con Iomaire 2016,2017;Haddaji et al. 2017b |

| The relevance of mentoring | It is crucial to have a mentor. |

Knutson and Schmidgall 1999;Mac Con Iomaire 2008;Abdullah et al. 2009;Ibarra et al. 2010;Martin and Bernard 2013;Harris and Giuffre 2015;Remington and Kitterlin-Lynch 2018;Dashper 2019

|

2.3. Research hypotheses

Following the theoretical context discussed above, we can propose the following hypotheses:

H1. The entrepreneurial attitude has a positive influence on a chef's career expectations.

H2. The perception of barriers to a chef's progression has a direct effect on their career expectations.

H3. The perceived workplace environment can deter female chefs from having positive career expectations.

H4. If chefs acquire the needed skills for their profession at the workplace, it will enhance their career expectations.

H5. Mentoring has a positive effect on a chef's career expectations.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Reliability test of the variables

Table 3 shows the test results for the reliability and the validity of our measurement model (Hair et al. 2011). We used composite reliability (C.R.) coefficient to test the internal consistency reliability. All constructs showed values above the suggested threshold of 0.7 (Nunnally and Bernstein 1994). We tested the reliability of the indicators through the absolute correlations between the items and their constructs. All indicators were over or close to the suggested value of 0.7. To assess the validity of the measurement model, we examined convergent and discriminant validity. All the average variance extracted (AVE) values were at least 0.5 (Fornell and Larcker 1981), indicating sufficient convergent validity.

We checked that the AVE's square root for each construct was higher than the correlation with the other constructs to check discriminant validity (Fornell and Larcker 1981).

Note: Under Discriminant Validity, the diagonal's bold values represent the square root of the AVE and the other values are the correlation between the different constructs.

Mentoring does not appear since there was only one related question.

We assessed the non-respondent bias using Multiple Group Analysis (MGA) in PLS and checking that the relationship's path coefficients were significant (p-value).

3.2. Fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis

We analysed the data using fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA). The fsQCA identifies patterns or combinations of causal conditions leading to an outcome (Ragin 2008). These factors can be necessary or sufficient for the outcome. Sufficient conditions or combinations of conditions are those that produce the effect. Essential requirements are those that if they are not in place, the result will not occur, but their presence does not guarantee the outcome (Dul 2016).

In this study, we are interested in evaluating the combination of conditions that produce high levels of career expectations in professional chefs. Therefore, we defined a chef's expectations as our outcome and a set of conditions, such as skills learned at the workplace or entrepreneurship attitude, as independent measures. The first step in the process is to calibrate all the measurements or constructs into fuzzy sets. Calibration is the conversion of the original measurements into values ranging from 0 to 1. Each value indicates the degree of the case membership to a group. Thus, 0 means no set membership and 1 shows a full set membership. We usedRagin's direct method (2008) to transform the values, employing three qualitative anchors for the calibration. Similar toWoodside (2013),Beynon et al. (2016), andDul (2016), we established that a full membership threshold was the point covering 90% of the data values, with the crossover point in the median and the full non-membership cut-off in the tenth percentile.

We applied the proposed calibration method to our five constructs and one item, all measured by a 5-point Likert scale. We employed the fsQCA algorithm after the calibration using the fsQCA 3.0 package (Ragin and Davey 2019). We created a truth table of representing each possible combination of predictors. The algorithm classified the observations in each set based on calibration values of each predictor. The truth table was then refined using frequency and consistency (Ragin 2008) for the final stage of the analysis. Frequency accounts for the number of observations in each combination of conditions. As a frequency threshold, we used a minimum of one observation to deal with a medium sample (Ragin 2008).

Consistency indicates the degree to which a subset relation has been approximated (Fiss 2011). It was similar to the significance of statistical models (Schneider and Wagemann 2010). We fixed a cut-off of 0.8 for consistency, which is higher than the minimum threshold recommended byRagin (2008). Thus, we included in the analysis only those configurations represented by a minimum of 1 case (Fiss 2011), and we codified sets with a consistency higher than the 0.8 thresholds as 1, with consistent, sufficient conditions for the outcome, and the remaining settings as 0.

We used the Quine–McCluskey algorithm to minimise the truth table and obtain the final solutions. The fsQCA produces three solutions: the complex, the parsimonious, and the intermediate. The differences between the solutions depend on the logical reminders used in the minimisation process. Logical reminders are configurations without observed cases (Rihoux and Ragin 2009;Schneider and Wagemann 2010). We have the intermediate solution that includes those configurations with unobserved cases possible for the outcome between the complex (without logical remainders) and economical solution (with all logical remainders). These solutions are claimed as superior to the others (Ragin 2008), as they do not remove any necessary conditions.

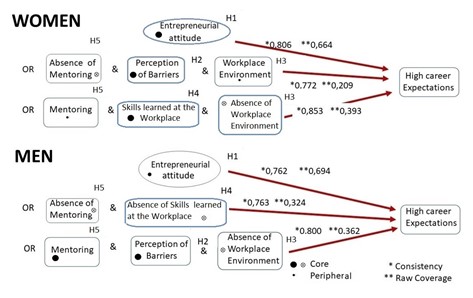

Note: Black circles (●) indicate the presence of a condition, while rings with "x" (⊗) indicate its absence. The blank cells represent conditions that "do not matter." Core elements of a configuration are marked with large circles and peripheral components are marked with small ones.

Table 4 presents the analysis results for the men and women subsamples. The consistency measure represents the proportion of cases in a configuration or a solution that showed the desired outcome. In other words, it captures the extent to which a given combination or solution is a sufficient condition for the result (Ragin 2008). All the configurations in both subsamples showed consistency values above the suggested cut-off level (0.75), indicating that the solutions' structures are sufficient for chefs to have high levels of expectations.

The solution coverage indicates the proportion of the chefs' high level of expectations explained by the solution (Ragin 2008), and it is similar to the coefficient of determination in a regression. In our case, we obtained solution coverage of 0.819 and 0.856 for the women and men subsamples, respectively. Thus, our solutions were able to explain a large proportion of chefs' high level of expectations.

Table 4 also reports the consistency, raw, and unique coverage for each configuration. The configuration coverage reflects how much of the outcome is explained by each solution. The setting's primary scope in the solution measures the proportion of cases that each configuration can describe. In contrast, the unique coverage measures the percentage of issues that can be explained solely by that configuration (Ragin 2008).

We differentiated between core and peripheral elements (Fiss 2011). Core conditions are those that show a strong causal relationship with the outcome. They are present in both the thrifty and intermediate solutions. Peripheral conditions are eliminated in the parsimonious solution and reflect a weaker causal relationship. The core/peripheral analysis of these solutions' elements indicates that the entrepreneurial attitude is a core condition that, when combined with other peripheral conditions that are equally effective (Fiss 2011), drive chefs' high career expectations.

For high career expectations to occur, solutions W1 (for women) and M1 (for men) reflect that an entrepreneurial attitude is the most critical path. Regardless of the chef's evaluation of the other characteristics, the entrepreneurial mindset is a sufficient condition leading to high career expectations. The high levels of basic coverage shown in the results (0.664 and 0.694 for women and men, respectively) indicate that in more than two-thirds of chefs showing high career expectations, we can also observe high entrepreneurial attitude levels. This conclusion also suggests the existence of small deviations in the background conditions for having high career aspirations.

The combination of a high perception of barriers and a perception of a demanding and competitive work environment with the absence of relevant mentorship encourages high career expectations in female chefs (solution W2). The perception of barriers and mentoring are core constructs, highlighting the importance of these factors in the outcome.

Additionally, female chefs' workenvironment positively contributed to their professional development. Still, it was less demanding, less competitive, and less hierarchical, combined with a high relevance of mentors, and contributes to high expectations (solution W3).

Regarding male chefs and the aforementioned entrepreneurial attitude, two paths lead to high levels of ambition. Solution M2 combines a perception of the work environment's low contribution to their professional development and low perception of the mentor figure. On the other hand, in solution M3, there is a combination of a high perception of barriers, the relevance of mentoring, and low values of a competitive workplace environment.

Finally, we performed a necessity analysis. A necessary condition is a condition present in every case that results in the specific outcome, while sufficiency indicates a state whose presence guarantees the effect. Thus, a necessary condition should cover all possible paths achieving the outcome. Our results suggest that there is likely no essential condition for having high career expectations.

Figure 1 outlines the research solutions or models determined from the statistical fsQCA. H1, which proposes a positive effect from chefs' entrepreneurial attitude, can be accepted as the main conclusion from the proposed hypotheses. It plays an essential role in raising career expectations by chefs, both male and female. While both groups indicate high consistency and solution coverage, it is higher in female chefs.

The perception of barriers to the professional advancement of chefs, as suggested in H2, has a positive influence on the secondary solutions as an operational condition. It is interesting to note that these solutions show a lower consistency and coverage in female chefs.

Finally, regarding H3, how chefs perceive the workplace environment and its influence on their expectations play a weaker role and could only be partially accepted. It only has a positive and peripheral presence in one solution for female chefs and an absent condition in the other two solutions in both female and male chefs. This seems like a logical conclusion since this environment affects more female chefs than male chefs.

H4, which suggests that learning skills at the workplace play an essential role in the chefs' expectations, shows a lower acceptance level. It is an existing condition in the case of female chefs and an absent condition in male chefs. Both offer similar consistency and coverage figures.

H5, which suggests that mentoring positively affects chefs' career expectations, could be partially accepted. It has been included in all solutions but with a more significant influence on female chefs since it shows a higher consistency and coverage either as an absent or present condition.

4. CONCLUSIONS

This research partially confirms the findings ofBoone et al. (2013) in the case of haute cuisine. Female and male chefs encounter similar barriers, mainly related to balancing work vs. private life and their expectations for a professional career. These barriers are either self-imposed or due to the perception of a harsh working environment. The absence of mentoring reinforces this effect. However, the obstacles for female chefs' progression, either self-imposed or caused externally, appear to be a relevant element in chefs' expectations toward their career. This contribution clarifies the theses ofBoone et al. (2013).

This study's main contribution is the crucial and independent role played by the entrepreneurial attitude of chefs, in particular female chefs, in regard to high career expectations in the haute cuisine profession. This variable plays a core role in the case of female chefs, but only a peripheral role for their male counterparts. This finding fills a research gap in the field and confirms the results of a minority stream of literature (Anderson 2008;Druckman 2012;Madichie 2013;Harris and Giuffre 2015;Aggestam and Wigren-Kristoferson 2017;Albors-Garrigos et al. 2019) that identify entrepreneurial activity as a critical enabler for the progression of female chefs. Other authors (Allen and Mac Con Iomaire 2016,2017) have outlined the restaurant's entrepreneurial attitude as a facilitating skill. Additionally, the research confirms the role modelling effect that entrepreneurial models have on entrepreneurial intentions in haute cuisine and celebrity chefs, as summarised by various authors (Albors-Garrigos et al. 2019;Madichie 2013;Zopiatis and Melanthiou 2019).

The influence of mentoring on a chef's career progression confirms previous literature (Knutson and Schmidgall 1999;Martin and Bernard 2013). Not only does mentoring act as a moderator for the perception of barriers and the harsh working environment, but it also functions as a lever of advancement in the hierarchy of the restaurant workplace (Harris and Giuffre 2015). It also operates as a critical factor in chefs' career expectations and satisfaction, notably in female chefs (Abdullah et al. 2009). Mentoring contributes to the fostering of culinary talent (Mac Con Iomaire 2008;Albors-Garrigos et al. 2019;Dashper 2019).

The harsh working environment reported by countless studies in the professional kitchen plays a controversial role in our research, but it is relevant. In the female sample, it had a peripheral influence in the absence of mentoring and a strong perception of barriers. On the other hand, in this same female sample, it was absent when there was peripheral mentoring and keen knowledge of the workplace's skills. The significance is explicit; when female chefs have a clear perception of the barriers, they may be better prepared for difficulties in the environment despite the absence of mentoring. Furthermore, mentoring and workplace learning removes the perception of a harsh kitchen environment. The memoirs ofBourdain (2013) andHamilton (2011), as well as the research ofDruckman (2012) andHarris and Giuffre (2015), provide various examples of these situations.

The research shows that workplace skills play an important role in female chefs’ progression; however, these skills are not as relevant in the male sample. Therefore, when combined with adequate mentoring, skills acquired in the workplace facilitate the absence of a perception of a harsh environment by female chefs. This moderation factor confirms previous findings regarding the crucial role that workplace learning has for female chefs' career expectations (Cormier-MacBurnie et al. 2015;Haddaji et al. 2017b;Albors-Garrigos et al. 2019).

5. MANAGEMENT AND POLICY IMPLICATIONS

What are the practical conclusions that we can draw from this research? There is a relevant suggestion for culinary schools to include entrepreneurial programs that promote initiative skills to foster students' drive in the sector (Yen et al. 2013). However, training programs must be tailored to meet real demand. There are already culinary entrepreneurship programs in place within some schools where students learn how to create and manage a culinary business and develop and present a business plan for a food service operation when seeking external finance. Finally, public and private financing for female chefs' entrepreneurial activities has been highlighted as a much-needed policy.

Culinary schools and apprenticeship programs should emphasise their training in improving the kitchen environment ethos. In this direction, mentoring could be incorporated during kitchen training.

Associations such as the American Culinary Foundation and the Women Chefs and Restaurateurs in America have demonstrated their capabilities as promoters of female chefs' careers through successful publicity of female chefs. They could be an excellent example for similar associations in Europe to follow.

Because gender balance in kitchens contributes to a more efficient organisation, hospitality and restaurant managers should bear this in mind when selecting, building, and managing kitchen teams, thus improving the kitchen's work culture.

Labour authorities, public authorities, and hospitality managers are responsible for implementing gender equality policies and proper workplace learning programs. Restaurant kitchens would certainly benefit from such measures.