1. INTRODUCTION

Over the last centuries, the history of Europe has been characterised by several crises, plagues, acts of terrorism, wars, earthquakes, and other natural catastrophes. The COVID -19 is not the first pandemic in the world. The world previously met other pandemics: the bubonic plague – the disease caused by the Black plague – which is likely to have reduced the world population by millions of people; smallpox, a pandemic already eradicated; cholera, which is still considered a pandemic; the Spanish flu, which killed 50 million people; and the Swine Flu (H1N1), among others (Huremović 2019).

With the COVID-19 pandemic, the hospitality industry has suffered one of its biggest hits ever. This crisis led to over two million deaths over the past year. According to theWorld Tourism Barometer (2021), after the 73% drop in international tourism recorded in 2020, demand for international travel remained scarce at the beginning of 2021. International arrivals in the seven months of 2021 were 40% below the levels of 2020. This means that international tourism presented levels 80% down when comparing to the same period of year 2019 (WTB 2021). Total losses of 2020 are equivalent to a loss of about 1 billion arrivals and 1.1 trillion dollars in international tourism receipts (UNWTO 2020).

The huge impact of COVID-19 on international tourism is now clear, with data from the UNWTO showing that, in May 2020, the cost of standstill was already three times greater than that of the 2009 Global Economic Crisis. The edition of theWorld Tourism Barometer (2020) showed that the almost complete lockdown imposed in response to the pandemic led to a 98% drop in the number of international tourists in May, compared to 2019. The Barometer also showed a drop of 300 million tourists and 320 billion dollars lost in international tourism revenue – more than three times the loss during the 2009 global economic crisis. Additionally, COVID-19 has led to economic and financial impacts distinct from those of other crises, e.g., the 2007-2009 global financial crisis.

This research aims to answer the following question: What are the impacts of COVID-19 in the hospitality industry? To answer to this question, the following objectives were formulated: i) to identify the COVID-19 impacts in the hospitality industry in Portugal; ii) to analyse how the pandemic might contribute to a transformation of the hospitality industry.

In this research, economic, financial, organisational, operational, and technological impacts are analysed through the lens of experts in the hospitality sector. Firstly, literature on the referred impacts of COVID-19 is reviewed. Secondly, the methodology of this study is presented. Thirdly, there is thematic analysis of a focus group with tourism experts on the impacts of the pandemic in the hospitality sector, and its long-term effects on the (re)organisation of the sector. The presentation of findings is followed by the discussion and conclusion. The final part consists of a reflection on managerial and theoretical contributions, together with suggestions for future research.

1. LITERATURE REVIEW

1.1. COVID-19 and Tourism

The tourism industry is considered one of the most economically important industries in the world (UNWTO 2019). However, from 2020 to 2021, with the spread of COVID-19, the tourism industry was highly affected. COVID-19 is a respiratory coronavirus disease caused by the virus “SARS- CoV-2”. The first alert to the World Health Organisation (WHO) came from China (Hubei province) in December 2019 and early in 2020. On 13th March 2020, the disease outbreak was declared a pandemic by the WHO, and Europe became its epicentre (Callaway et al. 2020;Jones and Comfort 2020). In Europe, the virus spread from Italy affecting neighbouring countries and leading governments to take drastic measures. Due to its rapid spread, the public health risk was considered mild to severe (Neuburger and Egger 2020). In March, the first recommendations to avoid nonessential travel to China, Iran, South Korea, and Italy were established, but soon extended to most European countries and U.S due to the high number of infected people (Neuburger and Egger 2020). One year later the pandemic situation remains the main concern worldwide, with the UNWTO outlined two scenarios for 2021. The first scenario pointed to a rebound in July, and the second scenario to a potential rebound in September.

Early in March 2021, in the World Tourism Barometer four factors were considered in these two scenarios: (i) the gradual improvement of the epidemiological situation, (ii) the continued roll-out of the COVID-19 vaccine, (iii) the increase in travel confidence, and (iv) a major lifting of travel restrictions.

Concerning the tourism industry, the impacts were severe, and tourism was declared as one of the most affected sectors. This led to a major downfall of the national and international tourism industry (Hoque et al. 2020). Overnight, the overall population was impacted by travel restrictions (Hall et al. 2020;Neuburger and Egger 2020;UNWTO 2020). The transport sector, one of the most important components in the tourism industry, was largely affected with the decline of international tourist arrivals. Most airlines, due to lower demand and to international restrictions, were forced to reduce or cancel flights (Darlak et al. 2020;Neuburger and Egger 2020). The hospitality industry was forced to close doors or reduce their staff due to low occupancy rates or government restrictions (Anzolin et al. 2020;Neuburger and Egger 2020). Catering and events were largely affected, and the cancellation of festivals and conferences represented a great damage to local communities (Skift 2020). The domestic travel market is expected to be the first to restart, in contrast with the international tourism market (Ranasinghe 2020).

This new reality has had devastating impacts in any country that found an outlet in the tourism sector, such as Portugal. Over the last decades, the tourism industry has become one of the main contributors to the Portuguese economy, where tourism employs around 400 thousand workers, contributes to 14.6% of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP), and is the main export activity (Turismo de Portugal 2020). However, the sector quickly sought to adapt to this new reality with new policies, such as flexi-cancellation policies, flexi-rates for all services and strict hygiene policies (Ranasinghe 2020).

1.2. Impacts of COVID-19 on the hospitality industry

1.2.1. Economic Impacts

According toMcKinsey and Company (2020, 1), the COVID-19 pandemic is not only a health crisis, but also “an imminent restructuring of the global economic order”. Its economic impacts have been particularly severe in international tourism. International tourist arrivals were estimated to drop 78%, causing a loss of 1.2 trillion dollars in export revenues from tourism and 120 million direct tourism job cuts – thus representing seven times the impact of September 11th, and the largest decline in history (UNWTO 2020). The International Air Transport Association (IATA) predicted a scenario of full year passenger revenues dropping 55% compared to 2019, and of air traffic falling 48% (IATA 2020). However, there are some claims that the pandemic could bring about economic developments in the tourism sector, which may emerge from this crisis as an increasingly sustainable industry (Mair 2020). The recovery is not the same or balanced for all countries. The rhythms are different. Domestic tourism is likely to recover first, as governments will strongly bet on local and regional travel (Hall et al. 2020;Ranasinghe 2020). International tourism saw some decrease with arrivals declining by 82% (comparing to May 2019), after falling by 86% in April, as confidence is slowing being restored and destinations started to ease travel restrictions (UNWTO 2021). According toIATA (2021), although air travel should improve, some late developments highlight that the recovery will take time and will be uneven. The impacts on airlines’ financials and on the restoration of economic and social benefits generated by aviation will continue negative.

There are political and industry pressures from companies for governments to ‘restart’ the economy as soon as possible, and to generate employment in a climate of huge economic recession, where lockdown has led to massive unemployment. TheInternational Monetary Fund (2020) projected the global economy to contract by 3% in 2020, much worse than during the 2008-09 financial crisis.

Governments can work on several measures to reduce economic impacts, such as to improve domestic tourism (Hall et al. 2020) or to reduce unemployment, in a context where millions of workers find themselves unemployed (Khan 2020). Wide dissemination of good hygiene practices can be a low-cost and highly effective response that can reduce the extent of contagion, and therefore reduce the social and economic cost (McKibbin and Levine 2020).Ashraf (2020) pinpointed that government social distancing measures have both positive and negative impacts. They are beneficial to reduce the risk of contagion, but they are negative to the economy. In the case of hotels or restaurants, social distance implies receiving and serving fewer people, which inevitably brings less revenue.

1.2.2. Financial Impacts

According toGoodell (2020) andYarovaya et al. (2020), the COVID-19 pandemic can have a significant impact on the functioning of the financial sector. In the financial area,Taleb (2007) introduced the concept of ‘the black swan metaphor’, which has been widely used in the financial literature. COVID-19 has been considered a ‘black swan’ event because it is a situation that has never previously occurred, and that has caused existing risk management models to fail to adequately evaluate the risk (Yarovaya et al. 2020, 4). Regarding financial impacts, certainly COVID-19 will shape future investigations of tail risk and financial markets (Kwon 2019). This pandemic has several unique characteristics that distinguish it from previous crises, and which open a new avenue for research on crisis and contagion. The black swan event attracts attention from the public and the media, resulting in higher social media engagement, and greater involvement from official mass media, television, newspapers, magazines, and online information portals.

Therefore, understanding the impact of COVID-19 on financial markets will be particularly important for investors and policy makers. Several financial indexes show that the most important factors underpinning changes in financial conditions are equity valuations and volatility (Cecchetti et al. 2020). It is very likely that the next time there is a sudden appearance of a contagious respiratory illness, there will concomitantly be a substantial global financial market reaction (Goodell and Huynh 2020). Hence, it is important to understand the current financial impacts, in order to avoid future crises or at least reduce their impact through preventive measures. This pandemic has had several financial impacts on the market: a negative EBIDTA (Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation, and Amortization), which delayed companies’ ability to recover in the stock market; late payment of rents and mortgages, among others. Meanwhile, there is great pressure in the market to end the lockdown, open borders, and allow free movement of people and goods. Multinational companies, as well as small tourism companies, financial markets and investors’ confidence have been affected by this crisis. Everyone wants to get back to normal (Sigala 2020). According toBanco de Portugal Statistic (2020) the most recent information for EBIDTA in Portugal is about 2019. There is a lack of information for 2020 BP statistic 2020, but considering the performance of other European countries about the same financial measure, it is possible to advance that the EBIDTA will decrease again.

1.2.3. Operational Impacts

The COVID-19 pandemic will most certainly lead to transformations in tourism and hospitality operations (Hall et al. 2020;Roman et al. 2020). It disrupted operations in the tourism sector and required major adaptations in order to mitigate impacts (OECD 2020). Some measures adopted were compulsory (e.g., social distancing, public hygiene protocols, the use of masks) (TUI Group 2020), others were voluntary (e.g., technology to reduce human contact or to check guests’ temperature at check-in) (Pflum 2020).

This pandemic has had several operational impacts, mainly in hospitality because of the need for social distance. For some hotels and restaurants, the reduction of wastage due to food surplus was a concern; hence, some provided staff with cooked food to take away. Other establishments provided financial aid or temporary jobs (Healing Manor Hotel 2020;Filimonau et al. 2020). New cleaning protocols were adopted in the sector, and the implementation of new layouts was established. In particular, the use of new technologies and digital tools has been one of the main concerns of the industry (Filimonau et al. 2020). In some countries, hotels were converted into temporary hospitals or rooms were rented by health staff (Catalan News 2020). According toHameed et al. (2021), buffet services also require radical changes. The traditional buffet may have been transformed into an assisted buffet, or replaced by individual food doses (Hameed et al. 2021;AzorHotel 2020). Other responses of hotels were the reimbursement of customer cancellations and the offer of “holiday vouchers” or discounts to encourage customers to return after the pandemic crisis (Catalan News 2020;Filimonau et al. 2020). All these decisions and transformations have profoundly affected operations in the hospitality sector.

Another operational impact from this crisis for airlines companies is the trend of flights to nowhere. As pinpointed byYoon and Wang (2020), because of some customers’ traveling needs, airline companies are preparing a few commercial routes to nowhere. According to these authors, commercial flights that go up then circle back home are finding an eager audience.

In the perspective of hotels, and according toGursoy and Chi (2020), more than 50% of customers are not willing to travel and stay in a hotel any time soon. Only about a quarter of customers have dined at a restaurant and only about a third are willing to travel and stay in a hotel in the coming months. This means that restaurants and hotels must adopt their operational procedures to convey confidence to potential guests and welcome them safely.

1.2.4. Organisational Impacts

The challenge posed by the COVID-19 pandemic has been tremendous. The virus has emerged as an important threat to human life due to its rapid spread and high degree of contagion. This led to important adaptations in the sector. According toRoman et al. (2020), the COVID-19 pandemic is an opportunity to reconsider and redirect tourism towards the future. Due to the uncertainties of the current situation, companies have had to adopt strategies, such as efficient communication with customers, work planning, digital enhancement, and teleworking. According toMao et al. (2020), when the pandemic emerged, companies supported and helped employees deal with this new situation. At the start of COVID-19, emergency management programmes were implemented. These provided long-distance work and training, which many companies adopted in order to keep their employees working. One of the adopted measures was using e-learning systems to train workers, or to impart new product information and skills. This can contribute to the general improvement of a business (Mao et al. 2020). Virtual platforms to hold meetings were introduced, which encouraged dialogue between employees. This facilitated the sharing of knowledge between members of the same group.

The role of organisational capital is, according toFilimonau et al. (2020), an important key during crises and disasters. Hence, Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) can contribute to the satisfaction of the staff during the COVID-19 pandemic. Through CSR, tourism companies can promote economic development and influence a huge number of stakeholders, in addition to contributing to environmental conservation, employee and customer satisfaction, and positive attitudes from the local communities (Levy and Park 2011;Mao et al. 2020), which are essential during a crisis or a disaster. Good CSR practices can influence the perception of job security, self-efficacy, resilience, and optimism among tourism staff. Therefore, CSR increases staff wellbeing through COVID-19 corporate responses.

1.2.5. Technological Impacts

Technology and innovation have been pointed out as some of the main solutions to re-open tourism and fight COVID-19 (Ranasinghe 2020;Sigala 2020). As pointed byUNWTO (2020), the optimisation of website performance has become of vital importance for the recovery of tourism businesses.

Technology has come to stay. As pointed by some authors (Gladstone 2016;Ivanov et al. 2018;Ritzer 2015), artificial intelligence, service automation and robots are increasingly essential to tourism and hospitality. With the pandemic, providing customers with socially distant experiences turned into a pressing need. Hence, technologies have become more important than ever. These technologies can be used by guests, for example, to avoid contact with employees. Digital assistants, like Alexa from Amazon or Siri from Apple, are used by Wynn Hotel in Las Vegas and in Aloft Hotels to help guests order their services without touching any object. Technology innovation can reduce risks during the pandemic by enabling a reduction in social interactions and improving cleanliness (Bitner et al. 1997;Johnson et al. 2015;Shin and Perdue 2019). The fully automated hotel check-in system, the self-service kiosk, check-in machines, housekeeping crews with UV technology-based equipment, electrostatic sprayers and cleaning robots are examples of what is being done in the hospitality and tourism industry (Shin and Kang 2020).

Mobility tracing apps, robotised-AI touchless service delivery, digital health passports and identity controls, social distancing and crowding control technologies, big data for fast and real time decision-making, delivery of material by humanoid robots, disinfection and sterilisation of public spaces, and measurement of body temperature are some of the measures adopted to build tourism resilience (Sigala 2020). Another important example is the Japanese chain FamilyMart which teamed up with Tokyo start-up Telexistence to test the idea of using a remotely controlled shelf stocking robot to restock grocery shelves (Yirka 2020). This type of technology is transferrable to the hospitality sector, where it can be used in the stocking of groceries or hotel amenities, thus guaranteeing social distance.

2. METHODOLOGY

The purpose of this exploratory study is to explore COVID -19 impacts in the hospitality sector, and to what extent this pandemic might transform this industry. A focus group with six experts in this field was carried out.

Focus groups are an appropriate methodological tool when “looking for the range of opinions, perceptions, ideas, or feelings that people have about something like an issue, behaviour, practice, policy, program, or idea” (Krueger and Casey 2015, 61). They are useful when the goal is to provide recommendations (Krueger and Casey 2015). In focus groups, participants influence each other, and the researcher may play several roles: “moderator, listener, observer, and eventually analyst” (Krueger and Casey 2015, 35).

Purposeful sampling was used to select information-rich cases whose study would “illuminate the questions under study” (Patton 1990, 169). Hence, the selected participants were experts in various areas within the hospitality industry.Table 1 briefly presents participants, who consented to be identified in the present article. All of them were executives and contributed to decision-making in their companies and associations. Their work experience in the tourism sector ranged between five and 25 years, and their average age was 41 years old. The diversity concerning their areas of expertise was expected to encourage discussion and enable the exploration of a range of views on the subject under analysis (Bloor et al. 2001).

A focus groups should be “small enough for everyone to have opportunity to share insights and yet large enough to provide diversity of perceptions” (Krueger and Casey 2015, 33).Morgan (1995) contends that small groups are particularly advantageous in the case of complex topics and when dealing with experts (as is the case of participants in this study) who might become irritated if they do not have enough time to express their views. According toBloor et al. (2001), the optimum size for focus group discussion ranges between six and eight participants. Hence, the selection of six focus group participants is believed to be adequate.

The focus group took place on 29th September 2020. A semi-structured interview guide with open-ended questions was prepared beforehand. The main objective of the focus group was to discuss the main impacts of the pandemic on hospitality, and future perspectives in the industry. The focus group was carried out on Zoom and recorded with the authorization of participants. The focus group session was open to a wider audience, who were given the opportunity to ask questions at the end of the session. The focus group session is available online, with participants’ consent. Although conducting the focus group online was a consequence of the pandemic, online focus group research may open new opportunities for data collection (Stewart and Shamdasani 2017).

The session was fully transcribed, as recommended byBloor et al. (2001). Thematic analysis was carried out in the original language (Portuguese) in order to avoid “getting lost in translation.” Only excerpts from the transcriptions were later translated into English for the purpose of inclusion in this article.

Thematic analysis was used for data interpretation (Braun and Clarke 2006;Clarke and Braun 2013). Thematic analysis searches for common themes across the whole dataset. In this study, the analysis was driven by the researchers’ previous knowledge of this research field. Hence, it was primarily a theoretical thematic analysis. A semantic approach was adopted – the themes were identified within the explicit meaning of the data, instead of involving assumptions underlying the data (Braun and Clarke 2006). NVivo was used to organise and define the themes.

3. FINDINGS

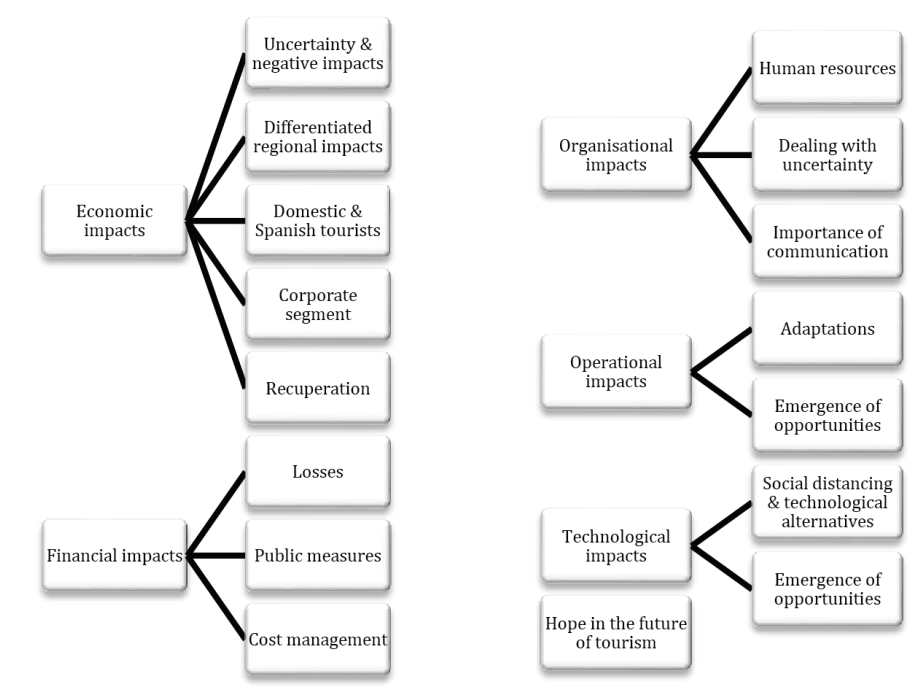

COVID-19 is described by participants as a “catastrophe”, particularly in contrast with the situation lived in the previous years by tourism in Portugal, which was described as “the real dream” (M3Fina), a “golden dream” (F2Orga), and as a period when the tourism sector was a “leverage […] for the Portuguese economy” (F2Orga). The huge impact of the pandemic in the tourism sector was mentioned by all participants. In this data analysis, participants’ accounts on impacts were divided into six main themes: economic impacts; financial impacts; organisational impacts; operational impacts; technological impacts; and hope in the future of tourism, which was a theme that permeated participants’ discourses. Figure 1 provides an overview of the main themes derived from thematic analysis.

3.1. Economic impacts

Regarding economic impacts, the huge economic impact of COVID-19 on the tourism and hospitality sector was highlighted by all participants. They emphasised the massive collective dismissals in large hotel chains, the possible loss of 50 million jobs in the tourism sector, and the negative impacts across the whole value chain, which is indirectly affected by the lower demand in the tourism sector (“A number of suppliers, such as fishers [...], had to reinvent themselves. […] they have started selling to the general public in order to survive” F1Econ).

Uncertainty makes the negative impacts in the tourism sector even more “devastating” (F1Econ). According to several participants, while the pandemic itself certainly brings uncertainty, the constant shift in governmental policy measures adds to this uncertainty. While F1Econ recognised that this shift is due to “governments dealing with something never experienced before”, this poses further hurdles to businesses:

One day it is the simplified lay-off […] then the other day it is the support for a gradual recovery, which does not allow for contracts to be suspended, and then, half-way, everything is inverted. […] We have a communication led by fear ‘stay at home, we have to contain the pandemic, we have to stop the numbers.’ Then everything is ok, and you can go out, ‘please go out and go on holidays.’ Meanwhile everyone has to return home (F1Econ).

Not only the Portuguese government is criticised because of the constant shifts in policy measures, but also foreign governments.

The press is also accused of generating “a pandemic of fear” (F2Orga). For F2Orga, the press should be made accountable for spreading fear instead of communicating clearly.

Lisbon and Porto were identified as the two regions where the impact has been felt most strongly. Since these are the most populated areas of the country, customers were most likely to avoid these areas, not only due to fear of agglomerations, but also due to the cancellation of events, which were one of the main attractions in these areas. Algarve suffered mostly due to its reliance on the English market, and Portugal being removed from UK’s travel corridor list. However, M4Hote highlighted how the Spanish market declined much less than more distant markets. Participants also underlined the importance of the internal market and its good reaction during this crisis; however, its size is not enough. Therefore, “it’s not what is going to be what makes us overcome this crisis” (M4Hote).

Participants shared different views concerning the recovery of corporate tourism. M1Tech cast doubts on a quick recovery for this type of tourism, due to video conferencing platforms providing a viable alternative to face-to-face meetings during the epidemic. On a more optimistic note, M4Hote mentioned the public measures in place to support the organisation of events. Moreover, he did not believe in video conferences replacing face-to-face meetings in the long-term, because “there are those things that you talk about during the meetings but rather during the coffee breaks.” Coffee breaks are the informal parts of events “where friendships are born”.

Participants hoped to “return to the golden dream” (F2Orga) of tourism development observed in Portugal in the years before the pandemic. They predicted the beginning of recovery for the Portuguese tourism sector from spring 2021. Participants were optimistic that Portugal as a tourism destination will recover after the pandemic, since the characteristics that make Portugal a “fantastic country” (F2Orga) and “the best destination in the world” (M4hote) will still be there, e.g., “the sun, the beach, the service” (M4Hote). However, the great challenge is to “keep the businesses alive so that we can keep on being the best destination in the world” (M4Hote).

Participants pointed out that “learning how to live with the virus” (F1Econ) is essential, as well as detaching oneself from the politics of fear. For participants, learning how to protect oneself is crucial in order to safely return to normal activities. Important measures highlighted by the participants are the continuous use of masks and continuous testing. F1Econ also underlined the need to implement rapid testing at work, schools, and airports, in order to “be able to return to normal more rapidly, […] and have some hope” (F1Econ).

F1Econ highlighted the importance of strategy and preparing for a best and a worst-case scenario during wintertime, particularly because “it’s not out of question that we’ll have to close again, not because we’re forced to, but because we’re going to lack customers, because most outbound markets to Portugal are closed” (F1Econ).

M4Hote also highlights the need to start preparing the future, particularly in what concerns necessary public infrastructures. In his opinion, Lisbon airport “can’t wait”, and “we can’t spend a year discussing whether we are going to build the airport or not”, or “still be discussing whether the airport will be in Montijo, Ota or Beja”. For F2Orga, the current moment presents an opportunity to stimulate tourism growth in the interior of Portugal.

3.2. Financial impacts

Concerning financial impacts, low occupation rates have had negative financial impacts, with the total income in this sector plummeting more than 70% in relation to the previous year. M3Fina and M4Hote were critical of the policy measures adopted to support the tourism sector during the pandemic. The measures in place consist of loans, moratoria and investment incentives. Despite the importance of these measures, these participants pointed out that such measures are expected to increase debt to unsustainable levels for a significant proportion of businesses (“The debt […] keeps on increasing like a snowball to be disassembled in the future” M4Hote).

In a sector where many businesses already had financial problems before the pandemic, these measures are likely to be insufficient to respond to their needs. A significant proportion of these businesses are currently considering insolvency:

According to surveys recently carried out by AHRESP, about 38% of businesses in Food & Beverage are currently considering insolvency. In the case of tourism accommodation, about 16% of those businesses are considering insolvency, so they discard the measures in place (M3Fina).

For these participants, the types of measures implemented by the government is only suitable for those companies which can pay the money back. The remaining companies can only receive support to solve past problems or problems triggered by the current crisis. In this context, M3Tecn advocates the need of capitalisation measures, so that a significant proportion of the companies in the sector can continue their operations and survive: “Besides the negative EBIDTA that is accumulating, equity is being strangled by the use of various financing measures offered by the state, but without forgiveness and without the concept of non-refundable” (M3Fina).

A measure regarded more positively was the new VAT reimbursement regime for event organisers with NACE code 82300. The measures at the company level proposed by participants focused on cutting expenses, namely reducing the compromise with fixed cost structures that are “too heavy” (M3Fina), resorting to outsourcing for non-core activities, and using technology wherever possible. Since many operational costs are inevitable, F1Econ advised businesses to consider which costs have to be maintained and which can be suspended. She highlighted the need to “be creative” and adapt to deal with the uncertainty: “It is not the strongest or the richest who will be able to survive, but rather those who can adapt” (F1Econ).

3.3. Operational impacts

Considering operational impacts, this pandemic required significant adaptations from establishments due to the need to ensure safer operations. For example, new procedures are now in place in restaurant establishments concerning the reception of products. In most establishments, suppliers no longer enter the premises of the restaurants for delivery.

Kitchen and service area operations were the least affected by COVID -19. For example, most of the procedures required due to the pandemic had already been implemented in M2Oper’s premises to guarantee food safety. However, in the dining room, adaptations were needed. There was not only more frequent sanitisation, but also different procedures. In addition, suppliers also had the need to adapt their own procedures, e.g., by distributing their product at different hours. Another aspect that M2Oper mentioned in relation to suppliers was their increased prices. Since suppliers’ total production decreased due to lower demand, this led to an increase in fixed costs and, consequently, in total costs. Hence, the increased cost of raw material for restaurant establishments is a further unexpected hurdle for restaurant businesses, according to M2Oper.

Not all the consequences of the pandemic were negative. A new type of customer emerged in the F&B sector. M2Operdescribed three segments of customers: firstly, the ones that go to restaurants and hotels; secondly, the ones that leave their homes, but do not consume in establishments, which allows for the exploration of the take-way business; and thirdly, the new type of client, which does not leave home (“delivery” customers). While the latter did not have a great impact in the business previously, this has changed. Hence, it is important to learn how to deal with this new customer, and to gather more information about them. For M2Oper, technology will be essential to fill this gap in knowledge.

The pandemic accelerated another trend in M2Oper´s establishment: the paperless trend. For example, records and documents to suppliers were moved to a digital platform. In addition, QR codes are now used to provide customers with the access to menus. In the hotel sector, M4Hote mentioned the increase in a disintermediation trend. This is due to cancellations being more easily handled in the case of direct bookings with the service provider. This trend has even instigated OTAs to start aggressive campaigns and reduce their margins, to prevent customers from getting used to booking directly. The pandemic also resulted in an increase in customers’ preference for booking much less in advance.

3.4. Organisational impacts

Concerning organisational impacts, the unexpectedness of the circumstances generated by the pandemic is summed up in the following sentence: “Hotels did not even have a key to lock the door because they had never been locked before” (F2Orga). This sudden change in two weeks generated feelings of distress among employees across all hierarchical levels.

According toF2Orga, it is important to learn how to deal with uncertainty, particularly in Portugal, a risk-averse country. She emphasised the need to find resources and to adapt. She also highlighted the crucial role of communication teams in organisations in communicating both with the external and the internal customer. Communication teams should spread a message of safety, and “channel [employees’] strength” towards the mission and goals of the business. Living in fear may “freeze” and “paralyse” people in organisations and leave them without the ability to react. F2Oper added that “this crisis reflects what was not working well in the organisation”; hence, businesses that already had problems before had a harder time coping with the pandemic. In contrast, businesses more oriented towards their workers had more resources and support to face this crisis.

According to F2Orga, “this crisis is a huge opportunity” for businesses, since it is a way of creating emotional compromise. She adds that “organizations have to once and for all look inwards and understand that they need to bring the people with them.” Therefore, she advocates the need for strong leadership, particularly at the emotional level, in order to “navigate the uncertainties”, “restore confidence”, and instil a sense of safety. With such a leadership, employees will pass on these emotions to customers as well. While during a crisis “it’s not so difficult to bring people together and put them to work in one direction”, she believed that it will be more challenging to keep employees’ motivational levels after the crisis. Hence, she claimed that employees cannot be forgotten thereafter.

The great challenge ahead, according to F1Eco, is also “to build teams almost from scratch” because many employees have left the organisation. She advocates the need to “reinvent” the human resources department, to have it “more integrated and not segregated from the organisation.” Hence, motivating teams is crucial. Several participants not only underlined the importance of motivating teams and bringing them together, but also described strategies to increase staff involvement in the organisation. Besides the importance of conference calls to bring together the whole team, involving teams in finding a solution for the current problems is also an important way of boosting their motivational levels. Employees should feel that they are the leverage for recovery and job maintenance, and that their ideas can have a global impact in the organisation, according to F2Orga. In his business, M2Oper involved employees in the development of new projects “to provide clients with different kinds of experiences that we didn't think of in the past”, such as the use of public space, which is currently being used more intensively. Regardless of whether all these projects go forward or not, they can make employees feel more involved in the organisation, particularly those who are not physically present in the establishment.

3.5. Technological impacts

Technologies also offer further opportunities to motivate and involve people, making them feel part of the organisation. Due to the widespread usage of mobile phones, it is now possible to spread digital information more easily. Information that was previously only shared with higher hierarchical levels, can now be easily shared with the whole team. Hence, people become less afraid of sharing ideas in the organisation.

M4Hote underlined the importance of qualified staff to handle the “bazooka” (term used to describe funding to avert crisis in the eurozone) and make the most out of this opportunity. Finally, F2Orga advocated a change in the Portuguese mentality concerning the human resources department. The role of this department should no longer be simply regarded as “to process salaries, holidays and disciplinary actions.” In fact, this department – described by F2Orga as “a lung for organisations” – plays a vital role in the renovation of organisations, through skill provision, and employee empowerment and involvement. Hence, this participant expressed her hope that the pandemic will contribute to transform businesses in this regard.

Regarding technological impacts and according to M1Tech, the pandemic had a huge impact at the technological level. Firstly, it accelerated trends, by increasing their rate of adoption. Secondly, new technologies also evolved. What were previously only prototypes, are now closer to becoming real. The need for social distancing has pushed the need for new technologies and digital alternatives across the customer journey. Moreover, hotels currently have less staff, but more questions from customers. For M1Tech, this is a great opportunity to implement technology that facilitates contactless communication and AI solutions, and thus overcome the previous reluctance of hotel managers, whose emphasis was on face-to-face communication and customisation: “Nowadays, we are not looking for face-to-face communication, and it’s important to offer alternatives” (M1Tech). The tendency observed in the last decades for customer-to-staff ratios to decline has been reinforced. Despite recognising the importance of this opportunity, M4Hote believes that “we cannot forget that this is an industry from people to people […] otherwise, we’re just offering beds”.

M1Tech pointed out other benefits of technologies. Firstly, they can provide better knowledge about the customer, particularly about new types of customers, such as the “delivery” customer mentioned by M2Oper. Secondly, AI can support customer orders, mostly in the case of this new “delivery” customer. Thirdly, technology can improve the guest experience during their stay, with functionalities such as consulting the menu, ordering room service, digital key, or online check-in and check-out. M3Tecn also pointed out how tracking technologies can promote customer safety by limiting the propagation of the disease in case a customer is diagnosed.

For M1Tech, although the impacts of the pandemic are huge, new opportunities have emerged for the hospitality sector to boost efficiency and effectiveness. Therefore, technology-related companies developing products for the hospitality sector have grown immensely during this period: “During the pandemic, we have managed to add 1000 hotels in the world to our platform. These are very positive signs in terms of technology” (M1Tech).

Another area of growth during the pandemic were food delivery platforms, e.g., UberEats and Glovo. Although these players were entering the Portuguese market at a slower rate than in other countries before the pandemic, they gained momentum in 2020.

Although consumer behaviour was not a topic directly approached during the focus group, participants referred positively to consumers’ unshaken desire to travel as a sign of hope for the future of tourism (“The day the air route [with the United Kingdom (UK)] opened, bookings rained down from the UK. People are eager to travel. They want to somehow forget this dark cloud that hangs over us all” F1Econ).

M4Hote believed that the pandemic will have no impact on the type of tourism demand in the long-term. Although some tourists might have discovered inland tourism, he did not believe that the type of tourism demand will be greatly affected: “some will collapse, but the buildings will not disappear, hotels will continue […] I have no doubt”.

Even though all the experts described COVID-19 as a catastrophe, this pandemic has also sped up important transformations in the tourism sector, specially at the economic, financial, organisational, operational, and technological levels as summarised in Table 2. Hence, COVID-19 might be regarded as a double-edged sword for the tourism sector. Only the future will tell what extent the transformations observed during this period will remain. The main transformations highlighted by the experts were: (i) the increase in domestic tourism; (ii) the advent of a new type of customer; (iii) the use of technologies with potential for improving efficiency, communication, service, and for gathering information about the customer; and (iv) the emergence of new distribution channels.

4. CONCLUSION

The negative impacts of COVID-19 most emphasised by the panel of Portuguese experts were the economic and financial ones. Uncertainty has led to a constant shift in governmental measures, which has exponentially worsened those impacts. Additionally, some public measures to support businesses may be insufficient to those companies facing greater difficulties.

This pandemic is more than a health crisis, since it also brings implies economic and financial problems (McKinsey and Company 2020). This crisis increased unemployment, as reinforced by research participants and previous studies (Khan 2020). Participants highlighted the importance of domestic tourism to sustain businesses during the pandemic.Hall (2020) also mentioned the importance of domestic tourism in a context where there are many restrictions on travel, including closure of borders. In the financial area, the COVID-19 pandemic was a ‘black swan’ event (Taleb 2007), i.e., a type of event cannot be predicted (Yarovaya et al. 2020). Participants highlighted that COVID -19 had numerous negative consequences in the financial area, such as the negative EBIDTA. Other studies have corroborated the financial impacts of the pandemic, such taxes, depreciation, and amortization), which delayed companies’ ability to recover in the stock market and mortgages´ late payment among others (Cecchetti et al. 2020;Goodell 2020;Yarovaya et al. 2020)

All the participants confirmed the importance of operational impacts in the tourism and hospitality sector. Some of the major adaptations reported were compulsory due to the measures imposed by the government, such as the new health measures to protect social distance. The growth of takeaway and home delivery, as well as and the implementation of new procedures for receiving products from suppliers was highlighted by some experts. The other transformations referred to by experts were related with reimbursement of customer cancellations, such as flexi-cancellation policies and flexi-rates.

Participants’ discourses also confirmed that adaptation is crucial for survival. This adaptation entails not only cutting costs, but also changing communication and motivational strategies, as well as operational procedures, including an increased rate of adoption of new technologies. These aspects corroborated the findings of previous studies, according to which businesses had to adapt to minimise the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic (Filimonau et al. 2020;Mao et al. 2020;Roman et al. 2020). Another aspect highlighted by some participants was the importance of increasing orientation towards employees, bringing them together and motivating them. As referred byMao et al. (2020), companies supported employees to deal with this new situation. Companies who can successfully do this may be the ones who manage to survive this crisis stronger than they were before, according to the panel of experts.

All the participants confirm that technology and innovation were some of the solutions to fight the effects of COVID-19 in the tourism industry. The most emphasised measures to minimise technological impacts were the implementation of QR code as a solution for reading restaurant menus, and new apps that can avoid contact with the public and provide information. The prevalence of technologies was stated as essential to the transition for a better communication and service to the hotel and restaurant industry.

Despite the difficult situation caused by the current crisis, some companies are successfully navigating it. Therefore, it is important to look at examples of good practices to generate knowledge and exchange experiences, taking advantage of this moment as an opportunity to improve some aspects in the hospitality industry that should have been changed a long time ago. This crisis may represent a huge opportunity (Roman et al. 2020) for the market and for the society.

Regarding the theoretical contributions of this study, its findings underline the impacts of COVID-19 in the hospitality sector and contribute to a better understanding of their scope and dimension. Results also show the possibility of systematising the main impacts in five main areas: economical, financial, organisational, operational, and technological. Furthermore, strategies to minimise the negative impacts of COVID -19 were explored in the focus group, together with opportunities generated by the current crisis. Although our findings are exploratory in nature, they suggest the relevance of investigating in greater depth to what extent this pandemic will lead to permanent transformations in the industry. A second important theoretical contribute is for the body of literature of COVID-19. Many authors are researching in different areas about the impacts of this crisis into the society. Nonetheless this research intends to enrich the impacts of this pandemic specifically on the hospitality sector, a less studied sector but one that suffered huge impacts with this crisis.

Hence, in terms of practical contributions for the industry, this study has brought about relevant insights for the understanding this reality. It proposes a range of measures (as shown ontable 2) adopted by several businesses and identified by several experts, which can support managers in decision-making. A second contribute for the trade is that this study also revealed players’ lack of knowledge of how to deal with a crisis of such a magnitude. It is essential to improve hospitality suppliers’ ability to adequately respond to situations of crisis. So various strategies were highlighted by the panel of experts to minimise the negative impacts of COVID-19. Thirdly, this study may contribute to the definition of structural measures by governments willing to recover the tourism sector and mitigate the impacts of the pandemic. Important highlights are presented in this article to help to strength a tourist strategy for the future.

Considering limitations, the main limitation of the present study concerns its small sample size. As such, findings cannot be generalised. The main impacts were detected in Portugal, but it is not possible to generalise them to other realities because even if some are similars, others depend on different external outputs such as: different growth rates of COVID-19 cases, crisis preparedness plans, the power of economy, the weight of tourism sector and so on. Each country has a concrete reality, different resources, and different reaction policies.

Concerning future research and to surface this limitation, those results could be confronted with other group of experts. Also, longitudinal research can be suggested in order to compare (present and past results). Another suggestion for future research is to identify other less studied types of impacts and investigate them. Studies related with consumer behaviour need to answer questions, such as: ‘how has this pandemic affected and changed consumption habits?’ It is also important to measure how the confidence in consumption and investment will be affected. Social impacts also need to be studied. It is important to identify and to understand the influence of social media communication in society. To what extent has the broadcasting of COVID-19 news impacted the society? Another important topic concerning the societal impacts of the pandemic is the importance of touch (Morgan 2021). How has this pandemic affected human mental health, after a year without hugs and affects? Since these impacts will change people’s lives, and the tourism sector, it is important to research them.