INTRODUCTION

The history of travel is as old as the history of humanity, starting with the journeys of explorers who realized that there were other worlds, goods, and treasures other than those of their own. Longing for distant places and curiosity about the unknown have encouraged people to undertake long journeys, write volumes of travel books, and prepare countless maps (Löschburg 1998). Travel has become one of the most interesting phenomena in our industrialized society. People travel more and more, as they do not feel comfortable where they live and work. To cope with their increasingly automated work, they need to escape from the burden of their routine life, and homes and travel is what make them alive. People often work just looking forward to their vacation, and some need to travel for work again. Vacations relax people, allowing them to work harder when they return to work, until the next holiday (Krippendorf 1986). At this point, we encounter travel itch as a concept used for people who have made traveling a part of their life, always desiring to travel, which they reveal by exhibiting certain behaviors. Travel itch is defined as ‘a feeling or desire that makes the individual want to continuously travel, feeling they need to move after staying motionless for a long time and thinking there are many places to be seen and many things to be done’ (Toksöz, Çapar and Dönmez 2019, 140). Travel itch refers to the strong desire to travel, constant thinking about traveling, and failure to give up travel. In addition, when individuals with travel itch do not travel, they have a feeling of discomfort, pushing them to do something for travel.

The phenomenon of travel itch is quite a new concept for tourism literature. In the study ofToksöz, Çapar and Dönmez (2019), a definition has been made using the expressions obtained from travel blogs written about travel itch. Information from blogs alone will be superficial in understanding the concept. To better understand the concept of travel itch, it is important to investigate how uneasy people with travel itch feel when they have an intense desire to travel and along with their travel attributes what kind of methods they use to cope with travel itch. For these reasons, a self-administered survey has been given to be able to benefit from the experiences of travelers from various countries who use the concept of travel itch to describe their travel desire and behaviors through social media. In this direction, the present study obtained data from travelers who reported to have travel itch personally, explored the motives of travel itchers along with key attributes and the travel characteristics, and determined the methods they use to cope with it. With the data obtained, the concept of travel itch will be examined within the motivation theories framework and this study will provide a better understanding of the concept of travel itch which is valued as unique in the tourism literature.

1. LITERATURE REVIEW

1.1. Travel Motivations

Travel itch is one’s deep inner desire to travel and can be explained with various travel motivations. There are extensive studies in the literature to understand travel motivations (Crompton 1979;Dann 1977;Iso-Ahola 1982;Klenosky 2002;Snepenger, King, Marshall and Uysal 2006;Park and Yoon 2009;Pearce and Lee 2005;Plog 1974;Uysal and Jurowski 1994) One of the first studies to examine the motives leading people to travel was published byLundberg (1971) and he defined 18 motives under the dimensions of ‘education and cultural motives, ethnic and other motives’. After this initial research, many studies have shown up in the literature. For example,Dann (1977) introduced push and pull factors that encourage tourists to visit a particular place or destination. Push factors are intrinsic motivations that push individuals to travel and consist of elements such as fun, rest, escape, and adventure. Pull factors are a destination’s physical characteristics, attractiveness, quality of service, and so on.Crompton (1979) classified travel motivations as socio-psychological and cultural motives. Socio-psychological motives were ‘escape from a perceived mundane environment, exploration and evaluation of self, relaxation, prestige, regression, enhancement of kinship relationships, and facilitation of social interaction’. Cultural motives were ‘novelty and education’. Then many studies have been undertaken to evaluate motivational factors.Iso-Ahola (1982) has defined motivation using a psychological perspective and introduced the escaping and seeking motivation model, a well-accepted theory by researchers. The theory consists of both personal and interpersonal escaping and seeking motives, which one unconsciously accepts. An individual performs recreational activities for two main reasons: seeking (for an individual psychological reward through travel) and escaping (from monotonous daily life) (Iso-Ahola 1982).Kozak (2002) has examined tourist motives under four headings: culture, pleasure-seeking/fantasy, relaxation, and physical, found the most effective motives for tourists in choosing a destination as relaxation and pleasure-seeking (Kozak 2002).Park and Yoon (2009) examined the motivations of Korean rural tourists as ‘relaxation, socialization, learning, family gathering, novelty, and excitement’.

However, Maslow's hierarchy of needs is frequently used in explaining the various motives of travelers and in examining the travel behaviors of tourists (Yousaf, Amin and Santos 2018). The hierarchy of needs examines human behaviors at five different levels. Meeting a need directs the individual to the other need at a higher level, whereby the hierarchy is formed. Moving to a higher level can only be achieved by sufficiently meeting the need at a lower level. In this hierarchy, physiological needs associated with the basic needs of individuals such as food, drink, and shelter are included in the first step. When this hierarchy is applied to the tourism industry, physiological needs are the basic needs that individuals expect a destination to meet. These needs include proper facilities for individuals, including the availability of suitable accommodation during their stay at the destination and presence of restaurants offering good quality food and beverages. These needs constitute the main motive for all travelers. The second step of the motivation pyramid is concerned with the safety of travelers. Destinations are preferred by visitors if they offer visitors a safe and secure environment during their stay. Travelers prefer destinations with a secure environment, making them feel safe and away from dangers during their visit.

The third step of the pyramid represents the establishment of both healthy relationships and connections that create a sense of social belonging. The sense of social belonging plays a positive role in motivating tourists to choose a destination. Individuals tend to travel to specific destinations in order to establish strong social ties with family and friends or with local people in the destination. The fourth step is about self-esteem, where individuals travel to influence friends, family, and relatives, as well as other people and seek to achieve a higher social status. In the last step, called self-realization, individuals consider travel as an activity through which they can develop special skills by doing something that challenges them. Self-realization in tourism can also be related to the activities in which individuals are involved in doing something for the benefit of society (Maslow 1943).

Based on Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs theory, also TCL (travel career ladder) and TCP (travel career patterns) created a hierarchy of travel motivations. The TCL theory combines leisure and career in tourism together and proposes that motivations vary according to the experience of travelers (Pearce and Caltabiano 1983;Moscardo and Pearce 1986). On the other hand, TCP adopts the TCL’s patterns with some modifications. TCP focuses on motivation factors rather than a hierarchy among travel motivations and argues that during travel careers a traveler will have a changing motivation pattern (Pearce and Lee 2005). According toPearce and Lee (2005), those with high-travel experience have more self-development (host-site development) and nature seeking and those with low-travel experience have stimulation, self-development (personal development), self-actualization, security, nostalgia, romance, recognition. However, regardless of travel experience, it is determined that the most important motivation factors for all travelers are escape/relax, novelty, relationship, and self-development.

Travel motivations play a critical role in understanding the psychology underlying travelers’ behaviors and informing these individuals’ willingness to visit a particular destination. Therefore, understanding tourist behaviors and related factors are very important for the success of tourism planners (Yousaf, Amin and Santos 2018). Additionally, travel motivation is significant to identify segmentation of the market (Park and Yoon 2009) and describe consumption forms of tourists (Swanson and Horridge 2006).

1.2. Concept of Travel Itch

Change in travel behavior of modern tourism consumers accompanies the new concepts in tourism and travel literature. As one of these concepts travel itch deserves to be introduced into tourism literature and researchers’ attention.

In medical literature, “itch” is described as an unpleasant sensation that triggers a desire to scratch. And there is pleasure when it is scratched (Bautista, Wilson and Hoon 2014). There are several studies about itch in the literature of medicine as a medical concept. But this study is the first to adopt the concept in social science and tourism literature.

In tourism area, travel itch as a concept can be traced in the travelogue ofRoy (1990) as “Dhubri Itch”. And recently it emerged in travel blogs as a concept used by people who travel constantly, and comprise the means of “travel bug”, “be beaten by a travel bug”. It is a desire that familiar to anyone who has traveled at least once. Rather than an unpleasant way it is mentioned mostly in a pleasant way as a tickling.

The concept is first literally defined byToksöz, Çapar, and Dönmez (2019:140) as “a feeling or desire that makes the individual traveling continuously, feeling to move after staying motionless for a long time and thinking there are many places to be seen and many things to be done.”

There are several concepts, including ‘wanderlust’ ‘travel desire’, ‘travel motivation, and ‘travel intention’ to emphasize the desire to travel in the literature. Whereas desire is referred to as “a state of mind whereby an agent has a personal motivation to perform an action or to achieve a goal”(Perugini and Bagozzi 2004, 71). Travel desire is a feeling about traveling (Gursoy et al. 2022, 4).Gray (1970) defines wanderlust as a type of tourism activity performed by tourists who look for new and unusual things (cultures and places) (Hyde and Lawson 2003, 14). Travel desire is defined as ‘the individual expression of lust, or desire to undertake a particular kind of trip or to visit a particular destination given no economic or other restraints’ (Larsen et al. 2011, 270).

Travel motivation is explained as a key stage that triggers travel decisions before actual travel (Mansfeld 1992). On the other hand, travel intention expresses one’s intent to travel. It is a mental process that leads individual to action and transforms the motivation into behavior itself. And sometimes considered more effective than behavior to comprehend the human mind (Jang et al. 2009). According toPerugini and Bagozzi (2004: 72), desire differs in 3 aspects from intentions. First, the actions to be desired are expected to be less performable in contrast with intentions. Second, desires are stated as time indefinite and can be postponed until the next decision-making is planned. But intentions are relatively now-oriented. Third, intentions imply a commitment and a part of planning to achieve goals than desires, that is action-connectedness. Therefore,Perugini and Bagozzi (2004, 72) argue that desires should be distinguished from concepts such as intentions, attitudes, and goals.

However, these concepts completely do not indicate the concept of travel itch. Desire itself comprise motivation to perform an action, tend to less perform and time indefinite, but travel itchers feel the discomfort of not being able to travel and try to lessen this discomfort by doing some travel related actions e.g. watching travel videos/photos, making plans of next trip, reading travel blogs, etc. Cause when it is scratched one gets pleasant and relaxed. This scratching lasts until to action (travel), and after the trip is over discomfort of itching (displaying the same behavioral characteristics) arises again and goes on as a repetitive circle (Capar, Toksoz and Pala forthcoming 2022). AsRoy (1990) implied no matter how hard it is, after a trip is over, it will reoccur. That process tends to be characterized by anyone who had travel experience at least once.

Therefore, it is necessary to examine the concept of travel itch, as a new concept for tourism literature. And more research is needed to understand the antecedents and consequents of travel itch.

In this research, travel itch is handled as a concept that is examined travel motives together with attributes of travel itchers. In the light of findings, it is tried to explain the itchers travel motivations within the framework of motivation theories and is tried to re-define the concept.

2. METHODOLOGY

The main purpose of the study is to examine the concept of travel itch by revealing the travel motives and characteristics of individuals who have travel itch and their methods of coping with it. The study follows an exploratory approach by using one of the qualitative research designs; phenomenology. Research questions are:

What are the basic motives of individuals who have travel itch?

What are the travel characteristics of individuals who have travel itch?

How do they cope with that travel itch?

A questionnaire, prepared in line with the purpose of the study was sent online to individuals who have travel itch. Based on the prior theoretical meaning of the concept, the study used purposeful sampling to reach individuals who reported having travel itch on social media platforms (Facebook) and expressed opinions about it in travel groups. As the target population of the study consisted of people who have travel itch and share their experiences via social media (Facebook), and it is impossible to reach the whole population, the data was collected using an online questionnaire between January and December 2020.Morse (1994) states that the sample size should include at least six participants in phenomenological studies(Sandelowski 1995). Phenomenology is a method in psychology and descriptive qualitative study of human experience that investigates what is and how is experienced (Wertz et al. 2011). Investigating experiences raise interest in an interpretive paradigm, which may be better suited to understanding such a complex phenomenon. Due to these reasons, based on the experiences of travel itchers, this research was designed in phenomenology. The data was collected from a total of 30 participants by using an online questionnaire. The questionnaire which has open-ended questions were sent to travel itchers who used “travel itch” concept (familiar with) in their shared contents and travel groups on Facebook. During the data collecting process, researchers couldn’t conduct in-depth interviews because of the features of the sample group, e.g. international sample and time and lag constraints to make interviews. Instead, an online survey was used to capture a representative sample (Dolnicar, Laesser and Matus 2009). Thus, administrated method was thought to be useful to gain information in detail.

Open-ended questions in the questionnaire include; (1)What words first come to your mind when you think travel itch? (2)What are the reasons that make you feel travel itch? (3)How does traveling make you feel? (4)How do you satisfy/scratch your travel itch?

Firstly, attendants were informed about the survey and asked to answer the questions on a voluntary basis. 30 participants who agreed to participate in research filled the online questionnaire sent via a link to their message box.

A content analysis was used in the data analysis, where the categories were created based on research questions in line with the questionnaire (Krippendorf 2004). The data were evaluated using content analysis, and the results were visualized. Content analysis is a research technique used to make repeatable and valid inferences from the contexts in which texts are used (Krippendorf 2004) and enables researchers to reveal the contents embedded in the knowledge (Neuman 2006).

In the content analysis phase, peer debriefing was carried out to increase the validity of the research results (Creswell and Miller 2000). In this phase, peer qualitative research in the field of tourism was included in the study. One of the authors explained the entire research process to their peers and reviewed the results by receiving constructive feedback and approval from them. In addition, an audit trail was used to examine the entire study. A supervisor unfamiliar with the study made an objective evaluation of the results of the study and the research process, and the research results were rearranged accordingly. According toSilverman (2000), one of the two ways to increase the reliability of qualitative research is assessing inter-coder agreement. In order to increase the reliability of the study, three researchers first performed the coding, categorization, and theming processes separately. Then, the codes they developed were compared with the results produced independently, whereby the codes were cross-checked (cross-coding) (Creswell 2013). Afterward, the results were compared and discussed until the inconsistencies were determined and eliminated. In this way, codes are assessed with inter-coder agreement.

3. FINDINGS

3.1. Travel Itch and Travel Motives

3.1.1. The first words that came to mind regarding travel itch

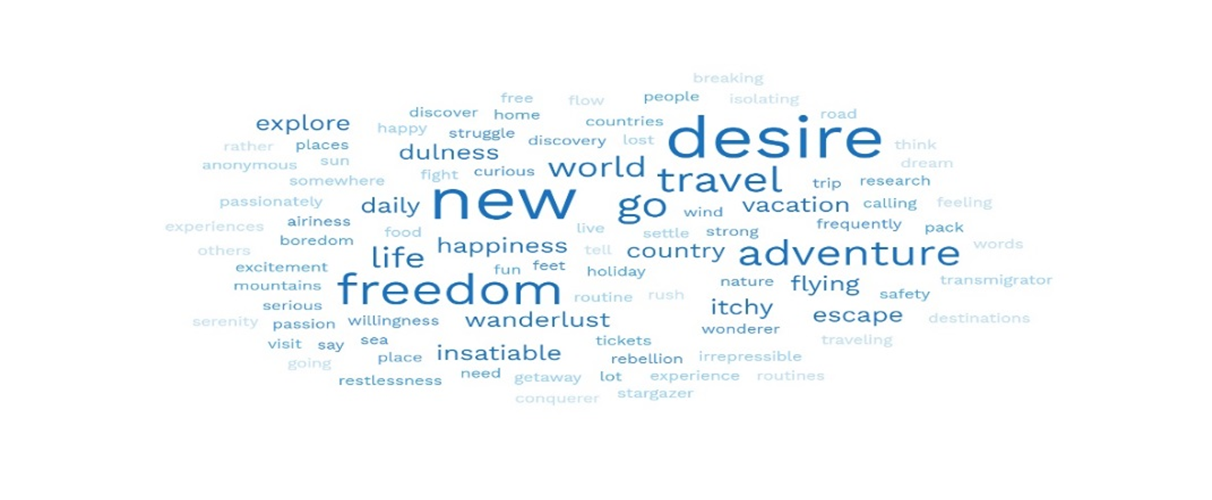

When individuals who have travel itch were asked to think of travel itch, the first words that came to their minds (Figure 1) are desire, new, freedom, travel, go, and adventure. Apart from these, words such as world, escape, life, vacation, wanderlust, and explore also stand out.

3.1.2. The travel motives of the individuals who have travel itch

The codes created as a result of the answers of participants who have travel itch to the question about their reasons for traveling were themed similar to the motives introduced byPearce and Lee (2005) in their study on tourists’ motivations. The codes were gathered under the themes of novelty, escape, self-development (host-site involvement), self-actualization, stimulation, and the travel itself, which are compatible with the motivation factors determined byPearce and Lee (2005). However, based on the statements of the participants who had a constant desire to travel and wanted to travel constantly, it was deemed appropriate to collect some codes under the theme of ‘the travel itself’. We can give an example to the coding of themes as follows.

Novelty: This theme included the codes of discover, curiosity, having fun, experiencing something new, and being happy. Under this theme, participants spoke more about the motives of experiencing something new, discovery, and curiosity.

Escape: This theme included the codes of escape from routine and boredom, to get rid of workload, and to be refreshed. Under this theme, participants spoke more about the motives of escape from routine and boredom and the need to be refreshed.

Self-development (host-site involvement): This theme included the codes of experiencing different/new cultures, new food, new people, new places, and learning new things. Under this theme, participants wanted to travel to new places, and also emphasized that they wanted to experience different cultures and food.

Self-actualization: This theme included the codes of challenge to myself, self-realization, and understanding life. Under this theme, participants considered their travels as an opportunity to get to know themselves and the world.

Stimulation: This theme included the codes of adventure-seeking and questions about unknown things. Under this theme, participants stated that their reason for traveling was to embark on different adventures.

The travel itself:This theme included the codes of interest of travel, bitten by the travel bug, to feel the sensation of the trip, wanderlust, need to travel, wanderer, and travel as a lifestyle. Unlike the motivation factors introduced byPearce and Lee (2005), this theme is a travel motive that can define those who have travel itch. Those with travel itch constantly desire to travel, think of traveling as a lifestyle, and have a strong desire to be on the road. The expressions of the participants who have this passion and hence the travel itch distinguish them from other travelers.

3.2. Travel Attributes

3.2.1. Travel preferences of individuals who have travel itch

As a result of the responses of those who have travel itch regarding their travel preferences based on their travel experiences, it has been revealed that destination features, travel style, travel, and accommodation styles are important in their preferences. More than half of the participants emphasized their travel style while stating their travel preferences. Most of them emphasized that they prefer to travel alone, while other participants emphasized that they want to travel with their friends or partners. Participants who declared their preferences regarding their destination features stated that they mostly preferred natural beauties.

Destination features:This theme included the codes of natural beauties, exotic trips, new food, different culture, and away from my country.

Travel style: This theme included the codes of alone, with friends, and with a partner.

Travel and accommodation type: This theme included the codes of unplanned, hitchhiking, couch-surfing, car trips, and adventure.

3.2.2. How often do travel itchers feel the itch?

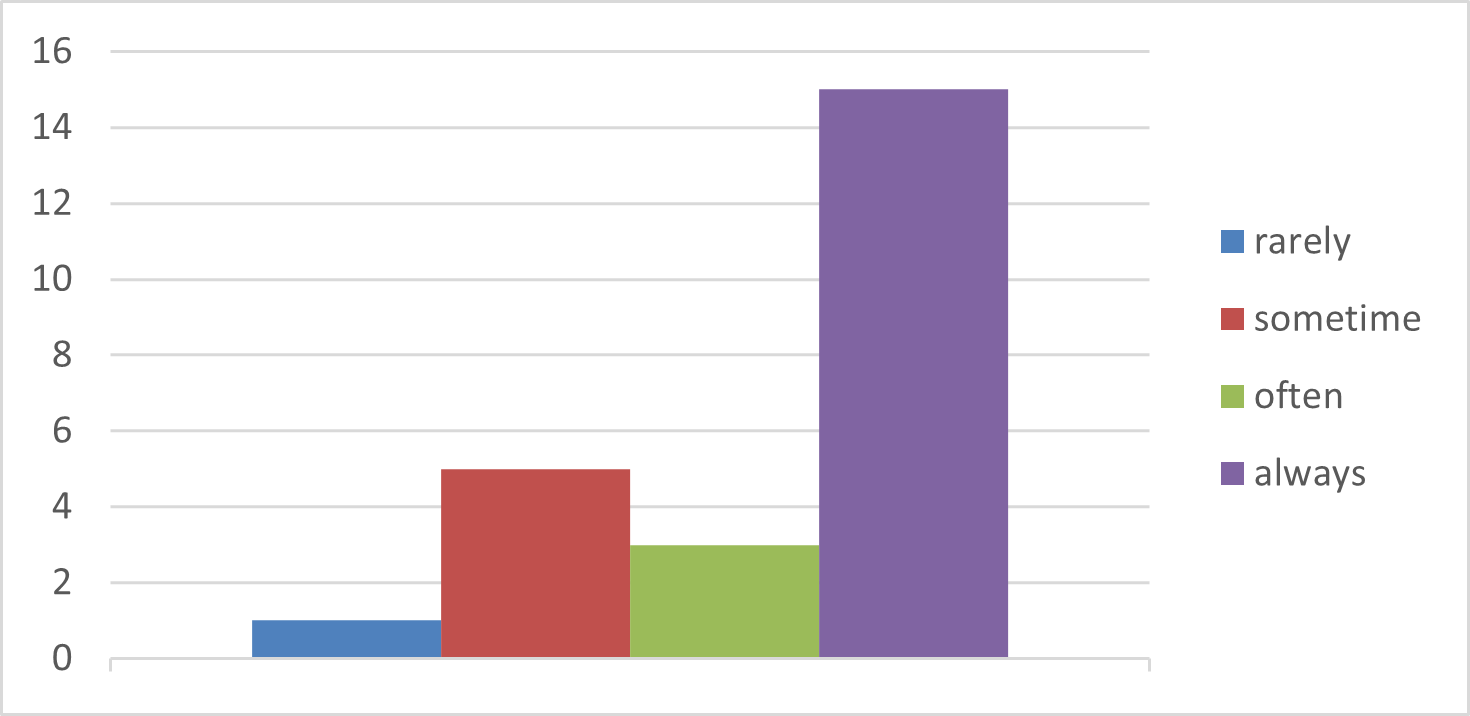

As seen inFigure 2, when they were asked how often they experience a travel itch, the vast majority of the participants stated that they ‘always’ had this feeling. In fact, this data shows that there is no specific time or duration of travel requests of those who have travel itch. It seems that this desire, and therefore travel, can happen at any time of the year.

3.2.3. The feelings about traveling of individuals who have travel itch

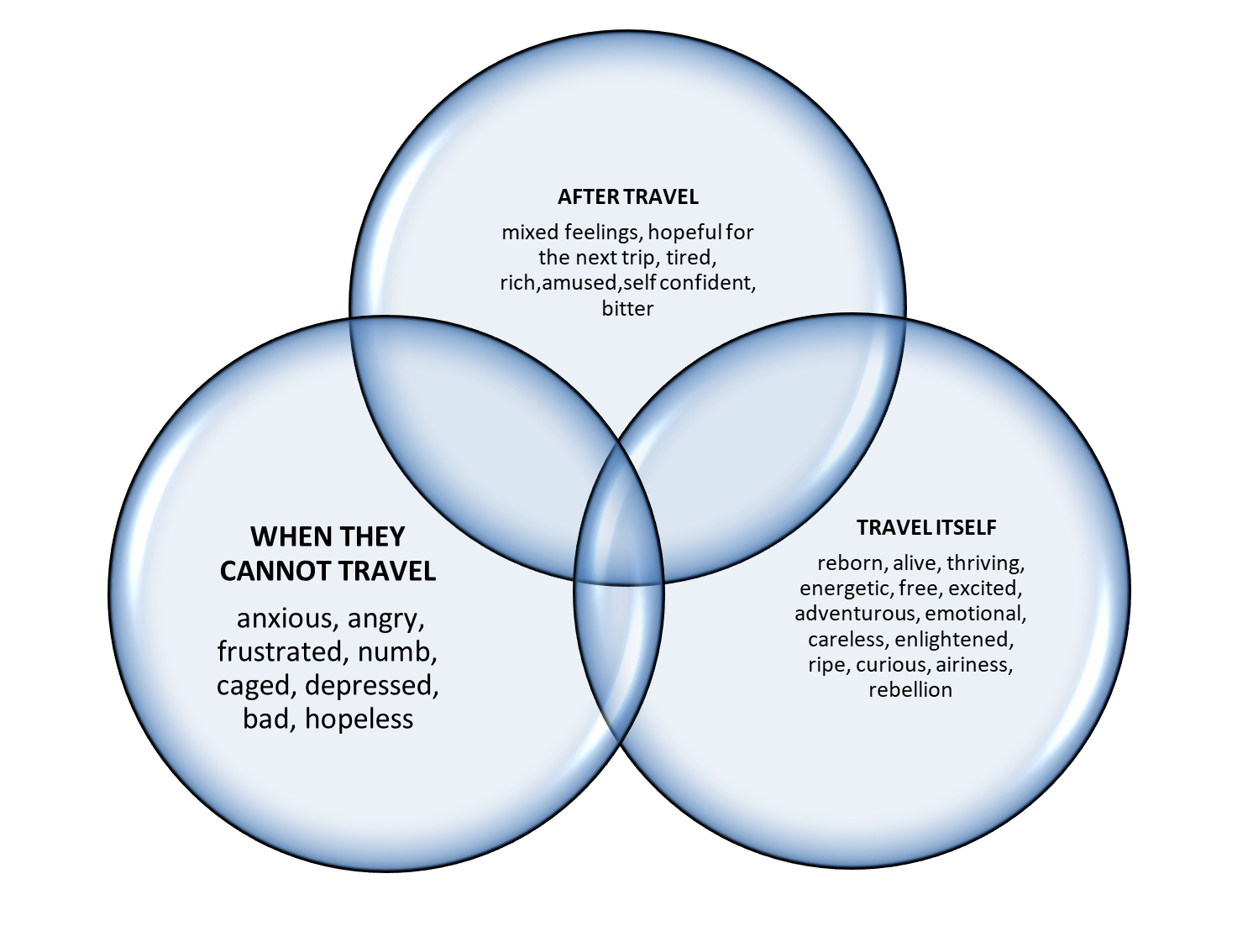

To understand what travel itch is, it is necessary to understand how travel feels to those who experience it. For this reason, as a result of the answers given by the participants to the question what they feel about travel, we grouped the feelings about traveling of those who have travel itch as follows: feelings about travel itself, after travel, and when they cannot travel.

Feelings about travel itself: This theme included the codes of reborn, happy, alive, accomplished, thriving, energetic, free, excited, adventurous, relaxed, emotional, careless, enlightened, ripe, pleasant, curious, airiness, and rebellion. While they expressed their feelings about travel, many of the participants mostly used the expressions of happy, free, excited, alive, relaxed, pleasant, and reborn.

Feelings after travel: This theme included the codes of sad, bored, nervous, mixed feelings (a combination of both the sense of accomplishment of being on the trip and the sadness of the trip being completed), hopeful for the next trip, tired, happy, pleasant, rich, amused, accomplished, self-confident, relaxed, and bitter. While talking about their feelings after a trip, the participants mostly used the expressions of sad, bored, hopeful for the next trip, and relaxed.

Feelings when they cannot travel: This theme included the codes of anxious, nervous, bored, angry, frustrated, numb, caged, depressed, sad, bad, and hopeless. While expressing their feelings when they cannot travel, the participants used the expressions of caged, sad, hopeless, and nervous the most.

As seen inFigure 3, there are some positive (e.g. happy, free) and negative emotions (e.g. sad, anxious) felt by those who have travel itch, after traveling and when they cannot travel. Positive emotions felt by participants regarding travel and after travel, including ‘happy, pleasant, accomplished and relaxed’ overlap with each other. Similarly, negative emotions experienced by participants both after a trip and when they cannot travel, including ‘sad, nervous and bored’, also overlap with each other. However, there is no similarity between their feelings for travel itself and those they have when they do not travel.

3.3. Methods to Cope with Travel itch

3.3.1. Coping methods for travel itch

In the blogs about travel itch, the authors mostly share suggestions for those who have travel itch like themselves on how to cope with this situation. When they were asked how they cope with travel itch, the participants considered the most appropriate solution as having a new trip to eliminate their travel itch. Other coping methods they have expressed were collected under the themes of experiencing different activities, planning and researching for future travel, and remembering past travel.

Traveling:This theme included the codes of traveling, short trips, take the road, exploring my city, and trips in my own country.

Remembering past travels:This theme included the codes of remembering, and looking at albums (old travel photos).

Planning and researching for future travels:This theme included the codes of thinking about upcoming trips, and researching new places to travel.

Experiencing different activities:This theme included the codes of taking virtual tours, dreaming, writing some travel stories, hosting, reading, watching TV, researching the meaning of life, getting inspired from different voyagers, start to learn a new language, long walks, and going outside.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

Research on the travel motivations has become perhaps one of the most focused issues in tourism and is still up-to-date.In this exploratory study, it is aimed to reveal the travel motivations of people with travel itch, which is a new phenomenon in tourism literature, and travel attributes and characteristics of travel itchers via their experiences. From this aspect, this is one of the first studies to examine the concept of travel itch in detail.

According to the results obtained in the study, individuals who have travel itch mostly described the concept of travel itch with the phrases of desire/passion, freedom, traveling, moving, and adventure. In addition, exploration, life, and the world are among the first words that came to their mind about travel itch.

In line with the expressions of the participants who have travel itch, travel motives of travel itchers (their reasons for traveling) are novelty, escape, host-site involvement, self-actualization, stimulation, and travel itself. These individuals travel to escape from their mundane lives and routines, to get away from their surroundings, to discover and experience new things, and to have the feeling of freedom. This information reveals the answer to our first research question. The codes and themes obtained from the expressions of the participants are consistent with the motivation factors and TCP theory specified byPearce and Lee (2005), except for the theme of travel itself. Based on the participants’ expressions, especially regarding the theme of travel itself, travel is one of the main motives that distinguish those with travel itch from other travelers and encourage them to travel which is a different finding for tourism literature.

Although in their studyPearce and Lee (2005) claim that travel motivations of people differ according to their travel experiences, results of this study revealed that travel itchers are motivated by ‘escape/relax, novelty’ factors that affect all travelers. Besides, their results show that host-site development is a motivation factor for high-level travel experience group; stimulation and self-actualization are motivation factors for low-level travel experience group which is in line with this study’s results in terms of the motives of all levels. Although we didn’t design the study based on motivation factors ofPearce and Lee’s (2005) travel career pattern (TCP), strikingly the expressions of travel itchers matched up with these career patterns. The claim byPearce and Lee (2005) that travel experiences affect travel motives was not supported in this study. However, the purpose of this study is not to control the relationship between travel experiences of travel itchers and travel motivations, but to find out which motivation factors, in the corpus of motivation theories, travel itchers are affected by. This result brought the exploratory nature of this study to the forefront.

Regarding the second question about the travel characteristics of individuals who have travel itch, the individuals have reported that they can travel ‘anytime of the year’ alone or with a partner, prefer areas of natural beauty, and feel trapped when they cannot travel. In addition, individuals who are constantly in search of travel can get rid of this feeling when they go on a trip and experience a repetitive desire to travel as an urge to travel again after each trip. They also want to have distant and exotic holidays in order to explore natural beauties and seek adventure. These individuals, who can travel ‘at any time of the year’, mostly prefer to travel alone, but they can also travel with a partner (spouse, friend, lover, etc.). Their travel patterns can be unplanned, hitchhiking, couch surfing, or traveling with their vehicles. Travel makes them feel happy and free, and they are excited to travel; they mostly have feelings of being caged, sad, hopeless, and nervous when they could not travel. Shortly after their travel is over and they return home, they plan their next trip and go on new trips.

Regarding the third research question, the individuals have reported using some travel-related ways to eliminate travel itch, such as planning and doing research into their next trip, dreaming about traveling, and most importantly, going on a new trip. Considering their travel characteristics, the most striking one is that most of those who have travel itch want to travel alone. This is because of both their motives for meeting new people, seeing new places, getting new experiences and their desire to travel. In addition, the fact that they look for their next trip after their travel is over, plan their future trips to cope with travel itch, and do research for this shows that travel itch is constantly happening.

Travel itch is not only an actual desire of which the effects are trying to be reduced or eliminated, but also is a recurring cycle. In the light of this information, it is possible to re-define travel itch as follows: “A cyclical pleasant desire process which arises with various motives and tried to be eliminated by traveling or doing travel-related activities.” The definition of travel itch differs fromToksöz, Çapar and Dönmez’s (2019) study, who stated that the only way to relieve travel itch is to travel. In their study, it was determined that travel-related activities, which are defined as travel itch symptoms, are methods of coping with travel itch, just like traveling. Some individuals feel, think and desire to travel more than others. It is important to distinguish them from all other tourists. Because they have a motivation to travel naturally. Travel tickles their minds, thoughts, and souls. Finally, this tickle entails them to travel (action) again and again. These individuals are travel itchers. By contributing the travel itch as a unique concept to the literature, this study values to fill the gap in the literature.

General tourism consumption patterns (Woodside and Dubelaar 2002) often begin with decision-making processes before traveling. However, the travel itch concept may play a role before any travel decision. Travel itchers, who always have the feeling of travel itch regardless of a specific place or time to travel, have the potential to become an important target market for the tourism sector. They are travelers who are already motivated to travel and make plans to get back on the road even just after a trip is over. Therefore, consumers who want to travel constantly can be considered as an opportunity by tourism businesses, tour operators, and destination planners. This consumer group is important in eliminating the seasonality of tourism activities. Appropriate marketing strategies can allow these individuals, who want to travel again as soon as their vacation ends, to travel more often and all year round. In determining the marketing strategies, it is necessary to define the changing travel characteristics of individuals (Amine and Smith 2009). As travel itchers constitute an important target market in tourism, it is also necessary to know and define their travel characteristics to determine relevant marketing strategies.

LIMITATION AND FUTURE RESEARCH

After all, the concept of travel itch, which was newly introduced with this study, will form the basis for future studies. This study contributes insights regarding TCP theory into tourism and travel literature. However, it has some limitations. First, the study did not conduct in-depth interviews to obtain more information about the travel characteristics of travelers who have travel itch. A study with in-depth interviews will be more useful in determining more precisely the travel types and destinations of travelers who have travel itch, and how they cope with this feeling. Secondly, as in the study ofPearce and Lee (2005), the relationship between the level of travel experience and motivation factors of travel itchers could have significant implications. Certainly, future research directions are needed in the pursuit of a more holistic theoretical framework for the phenomenon of travel itch.

Thirdly, since this study aimed to understand the concept of travel itch through the experiences of all travelers who reported to have travel itch (without destination constraints) instead of those in specific destinations, we could conduct a self-administrative survey. Based on this study, researchers can carry out future studies with travelers who have travel itch in one or more destinations. In addition, to have more information about travel itchers, a study determining the personality traits of them might be useful.