INTRODUCTION

Recent years witnessed impressive research on sharing economy resulting in collaborative consumption (La et al., 2021; Lim, 2020; Mohlmann, 2015). Sharing economy has emerged as a new economic model that progressed through the proliferation of shared services available to the consumers at the click of a mouse (Lee, 2020; Tsou et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2023). Shared accommodation refers to renting out excess space by individuals(hosts) to others (guests) for a short period of stay, generally done through intermediary online platforms (So et al., 2019). Individuals use accommodation-sharing platforms to secure accommodation before making travel plans (Kuhzady et al., 2020). For example, Airbnb, founded in 2007, starting with two hosts and three guests in San Francisco, has become a popular accommodation-sharing platform that offers short-term rentals to over 1.4 billion hosts worldwide (Airbnb, 2023; von Richthofen, 2022). Some researchers provided evidence to the paradigm shift of customers in favor of shared accommodation instead of traditional motel-hotel accommodations (Yuan et al., 2021).

The recent COVID-19 global pandemic has adversely affected the financial positions of the customers who intend to economize in tourism. One of the fruitful alternatives is sharing accommodation, which provides a unique touring experience and at the same time saves substantial amounts of money (Hwang et al., 2019). Several countries were embarking on resilience strategies to overcome the losses from the lost business in tourism, relaxing the mandatory lockdowns, and promoting domestic tourism. India is no exception to this. Being the second most populated country in the world, periodical lockdowns and social distancing norms forced the individuals and families to stick to their homes. Soon after the relaxation of lockdowns and as normalcy is slowly getting restored, travelers find domestic tourism as a fruitful alternative. According to the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) report, the tourism industry decreased by over 80 percent during the global pandemic. However, it is expected to return to normal (OECD, 2020). Thus, the present study aims to explore the factors affecting customers’ behavioral intention towards sharing accommodation, especially from a developing country’s perspective.

Though it may sound that studies on tourism (Dedeoglu et al., 2023) and hospitality post-pandemic seem repetitive and replication of previous research, but it is not so. This is primarily because consumer behavior has undergone a dramatic and paradigmatic change (Kandampully et al., 2023). Therefore, this study is attempting to address the following research questions (RQs):

RQ 1: What are the antecedents of consumers’ behavioral intention towards sharing accommodation? RQ 2: Are there any gender differences in the factors leading to consumers’ behavioral intention towards sharing accommodation?

This study contributes to the literature on tourism and hospitality management research in several ways. First, the post-pandemic consumer behavior towards sharing accommodation is examined. Second, a simple model is conceptualized to identify the antecedent conditions leading to sharing accommodation intention. Third, this study explores the gender differences in the behavioral intentions of sharing accommodation. Fourth, the results from this study would underscore the importance of desire and frugality in enhancing behavioral intention. Fifth, the study considers the role of perceived risk adversely affecting behavioral intention and materialism affecting the behavioral intention positively. Overall, the model offers valuable suggestions for the marketers interested in sharing accommodation research.

LITERATURE REVIEW

The antecedents and consequences of sharing accommodation have been extensively researched in tourism and hospitality research (Pan & Yang, 2023; Wang et al., 2016). Compared to traditional accommodation sources (e.g., motels), sharing accommodation provides a new experience to the tourists and brings community feeling to the participants (Meng & Cui, 2020; Sigala, 2018). Literature review reveals that some of the benefits of sharing economy include the creation, production, and distribution of scarce resources for the benefit of society, thus contributing to sustainability (Tsou et al., 2019). Shared accommodation has been studied in China (e.g. Zhang et al., 2023), India (e.g. Davidson et al., 2018), Italy (Forno & Garibaldi, 2015) and in developed countries in Europe, and USA (e.g. Palgan et al., 2017). The researchers contend that shared accommodation is a precursor to sustainability and effective utilization of resources (Belk, 2014, Botsman & Rogers, 2011).The research on shared accommodation has been so diverse that some scholars focused on the impact of personality characteristics, while others identified the motivational factors for adopting shared accommodation (Belk, 2014; Wang et al., 2019). As sharing accommodation involves risk, some researchers dwelled on various types of risks and their impact on consumer behavior (Lee, 2020; Yuan et al., 2021). From the marketing research standpoint, researchers studied the sharing practices: home-sharing, ride- sharing, crowdsourcing, and emphasized that demand-supply inequity of resources contributed to the development of sharing economy (Lim, 2020).

The demand for sharing accommodation has increased during and post-global pandemic as the financial resources for the individuals has adversely affected alarmingly. Individuals preferred to adopt sustainable consumption (Tran et al, 2022). The global pandemic affected all the nations indiscriminately, and the tourism and hospitality industry is one of the worst affected sectors (Gerwe, 2021). The present study’s context is India, the second largest populated country after China. The tourism and hospitality sector plays a significant role in economic development. After nearly one and half years of frequent lockdowns and mandatory distancing requirements, individuals and families slowly attempt to restore pre-pandemic life. What remains relatively understudied is the effect of desire (to continue tourism), frugality (cautious spending), risk, and materialism on the behavioral intention of tourists to avail shared accommodation during the post-pandemic period. Further, following gender research, it would also be interesting to study the gender differences in the behavioral intention of shared accommodation, particularly in a developing country’s perspective.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK AND HYPOTHESES DEVELOPMENT

Literature review reveals that most of the earlier studies on tourism and hospitality considered the theory of reasoned action (TRA) and the theory of planned behavior (TPB) as theoretical platforms for explaining the consumer behavior driven by the attitudes (Ajzen, 1991; Hsu & Huang, 2012). However, the decision-making and behavior of individuals in the presence of resource constraints are primarily dependent on environmental conditions (Asadi et al., 2021). Therefore, to explain the consumer behavior towards shared accommodation, which depends on the mood and emotional factors stemming from the environment, the model of goal-directed behavior (MGB) is beneficial (Perugini & Bagozzi, 2001). Furthermore, since desire, not attitude, is the driving force behind adopting shared accommodation, the predictive ability of MGB is more vital when compared to TPB and TRA, and hence some researchers use MGB as a theoretical platform in tourism and hospitality research (Turel et al., 2010; Yi et al., 2020). Therefore, the authors also follow the MGB theory as a base in this study.

In tourism and hospitality research, desire is the most critical variable that precedes all other variables influencing the behavioral intention as desire (Ryan & Desi, 2000). For example, some consumers desire to have experiences and interactions with local communities (Paulauskaite et al., 2017), whereas others desire to participate in sustainable consumption (Hamari et al., 2016). According to the model of goal-directed behavior (MGB) postulated by Perugini and Bagozzi (2001), desires rather than attitudes are the predictors of behavioral intention.

Extant literature reported that desire, a complex blend of an individual’s emotional and rational choices, significantly influences behavioral intention (Tsou et al., 2019; Turel et al., 2010; ). Furthermore, recently conducted studies found that the behavioral intention of adopting Airbnb was predicted by an individual’s intense desire (Hwang et al., 2019; Yi et al., 2020). Based on the above, the following hypothesis is offered:

H1: Desire is positively related to behavioral intention

Frugality is a multi-faceted and complex construct because individuals differ in frugality depending on their personality characteristics (McDonald et al., 2006). While some individuals attempt to save money rather than spend, and others are bargain hunters (Tatzel, 2002). Frugality is the degree to which individuals exhibit hedonism, i.e., spending as little as possible and extracting as much as possible—frugality at the extreme results in thrifty consumption and saving enormous amounts of money. Frugal consumers are cautious about their spending, and frugal practices include finding promotions and price discounts (Evans, 2011). It is more likely that frugal consumers exhibit the behavioral intention to share accommodation. Their primary motive is not to enjoy ownership but seek gratification from the concept of ‘money saved is money earned. A recent survey conducted on 398 US consumers found that frugality was positively associated with sustainable consumption (Evers et al., 2018). Thus, based on the available empirical evidence and intuitive logic, the authors offer the following hypothesis:

H2: Frugality is positively related to behavioral intention

In the tourism and hospitality research, one factor that was exhaustively researched is the effect of perceived risk on the shared economy (Cunningham et al., 2005; Floyd et al., 2004). Consumers perceive various types of risks: physical, financial, privacy, and performance, in using the shared accommodation (Yi et al., 2020). The greater the perceived threat, the more excellent the adoption resistance regarding the shred accommodation (Quintal et al., 2010). Since sharing accommodations are provided by private hosts who are strangers, it is difficult to vouch for their honesty, integrity, and psychological safety of the place of stay, thus resulting in increased risk perceptions (Obeidat & Almatarney, 2020; Stollery & Jun, 2017). Furthermore, the risk of privacy of the tourists’ information making online booking of the shared accommodation adds to the negative effect of risk on behavioral intention. (Krasnova et al., 2010; Lutz et al., 2018). Based on the available empirical evidence, the authors offer the following hypothesis;

H3: Perceived risk is negatively related to behavioral intention

Materialism is the degree to which individuals give importance to worldly possessions such as wealth, property, and ownership. The greater the degree of materialism, the greater satisfaction individuals derive from material possessions (Belk, 1984). Though extant research documented a negative relationship between materialism and sharing economy (Belk, 2014; Richins & Dawson, 1992), a recent study reported a positive association between materialism and the customer’s willingness to adopt sharing accommodation (Davidson et al., 2018). A cross-country comparison of consumers from the USA (developed economy) and India (developing economy) revealed that consumers in both countries expressed their willingness to participate in shared accommodation, though for different reasons. The US consumers were willing to participate in shared accommodation because of more fun and efficacy, whereas Indian consumers experience the perceived utility they get from shared accommodation (Davidson et al., 2018). The present study is conducted in the Indian context, a collectivist society where individuals are habituated to share resources. Therefore, it is reasonable to expect that materialism leads to the behavioral intention of sharing accommodation.

In their meta-analytic study, Dittmar et al. (2014) found that materialism results in negative consequences for consumers to decrease in satisfaction and well-being. Further, it was argued that in the process of acquiring material possessions, individuals spend an enormous amount of energy and time (Burroughs et al., 2013) and engage in unsustainable and environmentally non- friendly behavior by piling up unnecessary possessions. On the contrary, some researchers argue that materialist consumers, especially during the phases of economic downturn (e.g., during the global pandemic), shy away from wasteful consumption and engage in socially responsible behavior (Evers et al., 2018). Since the behavioral intention of shared accommodation is environmentally and socially desirable behavior, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H4: Materialism is positively related to behavioral intention

Individuals who believe in sharing accommodation tend to emphasize the utilization of scarce resources, environmental sustainability and engage in collaborative consumption (Albinsson & Perera 2012). Apart from the utilitarian benefits, individuals adopt shared accommodation because of their satisfaction from sharing (Tussyadiah, 2016). Furthermore, extant research reported that sharing accommodation increased customer satisfaction and customers’ reuse (Choi & Chu, 2001; Oh, 1999; Ren et al., 2016). Some of the reasons why behavioral intention leads to shared accommodation include the hedonic and utilitarian benefits, environmental-friendly behavior, and social influence (Tsou et al., 2019). Though individuals tend to use shared accommodation for different reasons, there is consensus among the researchers that behavioral intention leads to the adoption of shared accommodation. Based on the above reasons, the following direct hypothesis is offered:

H5: Behavioral intention is positively related to the use of shared accommodation

Studies on gender found significant differences between men and women in cognitive mapping abilities, preference for accommodations, privacy, reaction to stimuli, etc. (Kakad, 2000; Lawton et al., 1996; Shrestha, 2000). In marketing literature, gender has been extensively studied and found significant differences in consumer behavior (Coley & Burgess, 2003; Dittmar et al., 1995). For example, women tend to focus on details whereas men focus on information (Meyers-Levy & Maheswaran, 1991); women are easy to persuade compared to men (Eagly & Carli, 2003).

Gender as a moderator has been studied concerning purchase decisions (Richard et al., 2010; Zeithaml, 1985). In a relatively recent study conducted by Lee and Kim (2017), it was found that women travelers showed high involvement (i.e., perceived relevance of the object based on needs, values, and interests (Zaichkowsky, 1985:p.342) when compared to men travelers. There is consensus among the marketing researchers that women are more sensitive to the information when compared to males, whereas men are more satisfied than women in purchase decisions (Homburg & Giering, 2001; Mittal et al., 2001). In a recent study conducted, it was found that females were more satisfied with Airbnb’s location, whereas men were happy with the hygiene conditions (Sánchez-Franco & Alonso-Dos-Santos, 2021). As men and women process stimuli differently, it is expected that gender differences exist about desire, frugality, perceived risk, and materialism. Though gender as a moderator in these relationships has not been studied, the following exploratory hypotheses are proposed:

H1a: Gender moderates the relationship between desire and behavioral intention such that gender differences are more

noticeable for women compared to men.

H2a Gender moderates the relationship between frugality and behavioral intention such that gender differences are more

noticeable for women compared to men.

H3a: Gender moderates the relationship between perceived risk and behavioral intention such that gender differences are

more noticeable for women compared to men.

H4a: Gender moderates the relationship between materialism and behavioral intention such that gender differences are

more noticeable for women compared to men.

The conceptual model is presented in Figure 1. Figure 1: The Conceptual Model

A survey instrument was used to collect data. Since it is impossible to have a fixed list of respondents who have availed or are willing to help share accommodation, the authors used an online survey and purposive and non-probability sampling. Because frequent lockdowns and social distancing have become mandatory, the authors preferred snowball sampling and contacted the known customers first, and asked each of them to provide us with the individuals and families interested in sharing accommodation. Though some researchers seriously suspect the representativeness, the snowball sampling technique has been used in several studies (Duncan et al., 2003; Etter & Perneger, 2000; Lonska et al., 2021).

The authors have started data collection on 1st May 2022 and completed on 31st August 2022 (four months), and in all received 460 surveys which were complete. Google forms do not allow incomplete surveys because the respondents would not continue unless they answer each question. As Krejcie and Morgan (1970) contend that the minimum required sample size is 384 and when the population size exceeds 100,000, the requirement of incremental sample size is insignificant. Several researchers in the past used Krejcie and Morgan (1970) criterion of minimum sample size (Madhu et al., 2023; Rajasekar et al., 2022). Therefore, sample size is not a problem in this research. The authors have checked the non-response bias by comparing the first seventy-five respondents with the last seventy-five responses and found no statistical difference between these two groups.

Of 460 respondents, 209 (45.4%) were male and 251(54.6%) were female. With regard to the age, 273 (59.3 %) were in the age group of 18-24, 115 (25.0%) belong to the age group of 25-34 years, 30 (6.5%) were in the age group of 35-44 years, 35

(7.6%) were aged between 45-54, and 7 (1.5%) were above 55 years. As far as annual income is concerned, 72 (15.7%) were earning less than INR (Indian Rupees) 200000 ($3000), 35 (7.6 %) were earning between Rs. 200000 – Rs. 300000 ($3000

- $4500), 57 (12.4 %) were earning between Rs. 300000 – Rs. 400000 ($4500 - $6000), 34 (7.4%) were earning between Rs. 400000 – Rs. 600000 ($6000 - $9000), 56 (12.2%) had income between Rs.600000 – Rs. 800000 ($ 9000 - $12000), 48 (10.4%)

earned between Rs.800000-Rs.1000000 ($12000 - $15000), 56 (12.2%) earned between Rs.1000000 – Rs. 1200000 ($15,000

– Rs.$18,000), and 102 (22.2%) had more than Rs. 1200000 ($ 18,000).

The authors measured the constructs on Likert-type five-point scale (‘1’ = strongly disagree; ‘5’ = strongly agree). All the items

were measures with the items established in literature.

Desire was measured with four items adapted from Hwang et al., (2019) and Yi et al., (2020). The sample item reads as “I desire to book peer to peer accommodations like (Airbnb, OYO, etc.) whenever I need to stay outstation” and the reliability coefficient Cronbach’s alpha for desire was 0.92.

Frugality was measured with four items adapted from Lastovicka et al., (1999) and used by Evers et al., (2018). The sample item reads as “ I believe in being careful how I spend my money”, and the reliability coefficient Cronbach’s alpha for frugality was 0.84.

Perceived risk was measured with five items adapted from Mahadevan (2018). The sample item reads as “I feel risk about my loss of privacy while staying in peer to peer accommodations (Airbnb, OYO, etc.)”, and the reliability coefficient Cronbach’s alpha for the perceived risk was 0.86.

Materialism was measured with five items adapted from Ponchio and Aranha (2008). The sample item reads as “I like to spend money on premium hotels during my stays”, and the reliability coefficient Cronbach’s alpha for materialism was 0.87.

Behavioral intention was measured with four items adapted from Yi et al., (2020). The sample item reads as “ I think I will stay in peer to peer accommodations (Airbnb, OYO, etc.) in future”, and the reliability coefficient Cronbach’s alpha for behavioral intention was 0.93.

The sharing of accommodation was measured as a categorical variable (‘1’ = No; ‘2’ = yes).

The authors first checked the measurement model and did confirmatory factor analysis. This study used Smart PLS-SEM for

checking the measurement model and the results are presented in Table 1. Table 1: Measurement model (Reliability and validity of the measures)

As shown in the Table, the factor loadings for all the indicators were more than the acceptable levels of 0.7. The reliability coefficients for all the constructs were greater than 0.70, and the composite reliability for all the constructs were greater than 0.7, and average variance extracted (AVE) estimates were above 0.50 and acceptable(Fornell & Larcker, 1981).

The descriptive statistics - zero-order correlations, means and standard deviations were presented in Table 2. Table 2: Descriptive Statistics (Means, Standard Deviations and Correlations) a

|

Mean |

SD |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

6.Use of shared ac- commodation |

1.75 |

0.58 |

0.27*** |

0.12*** |

-0.02 |

0.11*** |

0.18*** |

1 | |

|

7.Gender |

1.55 |

0.49 |

0.12*** |

0.01 |

-0.02 |

0.12*** |

0.05 |

0.19*** |

1 |

Pearson’s zero-order correlations; *** p < 0.001;

Gender: ‘1’ = Male; ‘2’= Female

A preliminary analysis of the correlations reported reveal that there is no multicollinearity problem with the data as the correlations between the variables did not cross 0.80 (Tsui et al. 1995). The highest correlation was between frugality and behavioral intention was 0.79, and the lowest correlation was 0.11 between materialism and use of shared accommodation.

The correlation table shows that the correlations between the variables were less than 0.75, thus suggesting that multicollinearity is not a problem with the data (Kennedy, 1979). Further the variance inflation factor (VIF) values were less than 5, providing evidence that multicollinearity is absent in the data.

The authors also checked for the discriminant validity through heterotrait monotrait (HTMT) and found that the values were less than the threshold value of 0.90, except for behavioral intention which is slightly higher than 0.09. The correlation matrix, HTMT matrix, inner VIF values and outer VIF values are shown in the Tables 3,4, and 5.

Table 3: Discriminant validity using HTMT

As common method bias is an inherent problem in survey research, the authors checked for the common method bias by employing the Harman’s single-factor analysis. This study found that single factor accounted for 24.78% , which is less than 50% and thus provide evidence that common method bias is not a problem. Further, correlations between the variables were less than 0.9 corroborating that common method bias does not pose problem with the data (Bagozzi et al., 1991).

After checking the psychometric properties of the survey instrument, the authors performed path analysis and presented the results in Table 6.

Table 6: Path Coefficients

SRMR = Standardized Root Mean Square Residual d_ULS = The squared Euclidean Distance

d_G = geodesic distance

RMS Theta = root mean squared residual covariance matrix of the outer model residual

As shown in Table 6, the path coefficients were significant for desire (β = 0.28, p < 0.001), frugality (β = 0.57, p < 0.001), and materialism (β = 0.08, p < 0.05), were significant, and for perceived risk (β = - 0.01, p > .05) not significant. These results provide support to H1, H2, and H4, and do not support H3.

The path coefficient of behavioral intention to the use of shared accommodation was significant (β = 0.18, p < .05), thus supporting H5. The goodness-of-fit statistics presented in the bottom of the Table 6 reveal that SRMR = Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR), d_ULS (The squared Euclidean Distance), d_G (geodesic distance) and Root Mean Square residual covariance matrix of the outer model residual (RMS theta) provide good fit of the model to the data.

As far as interaction effect of gender is concerned, the path coefficient of interaction desire and gender was significant (β desire x gender = 0.39; p < .05), thus supporting H1a. The path coefficient of gender as a moderator between frugality and gender was significant (β frugality x gender = - 0.57; p < 0 .05), thus supporting H2a. The path coefficient of interaction term gender and perceived risk (β perceived risk x gender = 0.24; p < 0 .05), and the path coefficient of interaction term of gender with materialism (β materialism x gender

= 0.18; p < 0 .05) were significant, thus supporting H3a and H4a.

The path diagram is presented in Figure 2. Figure 2: Path diagram

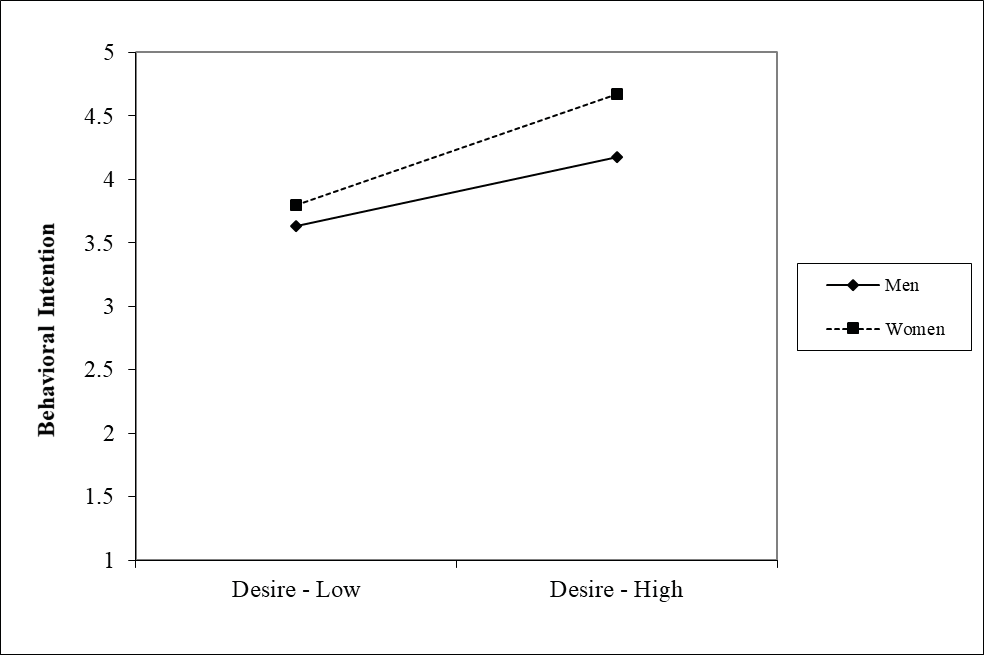

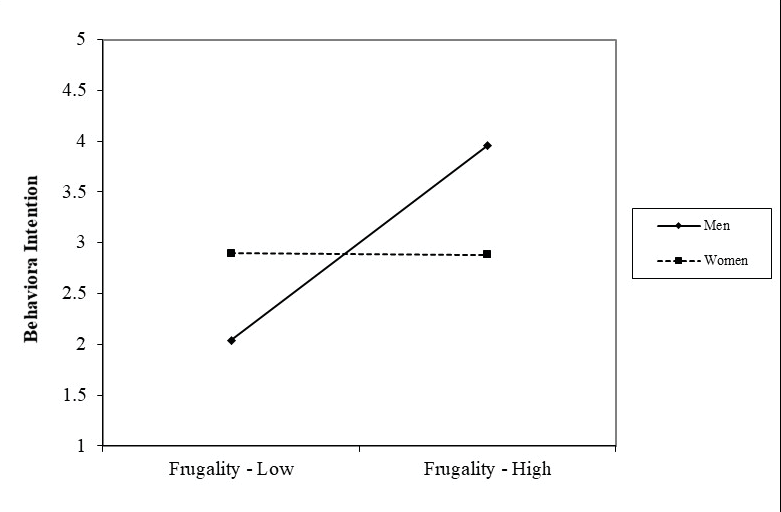

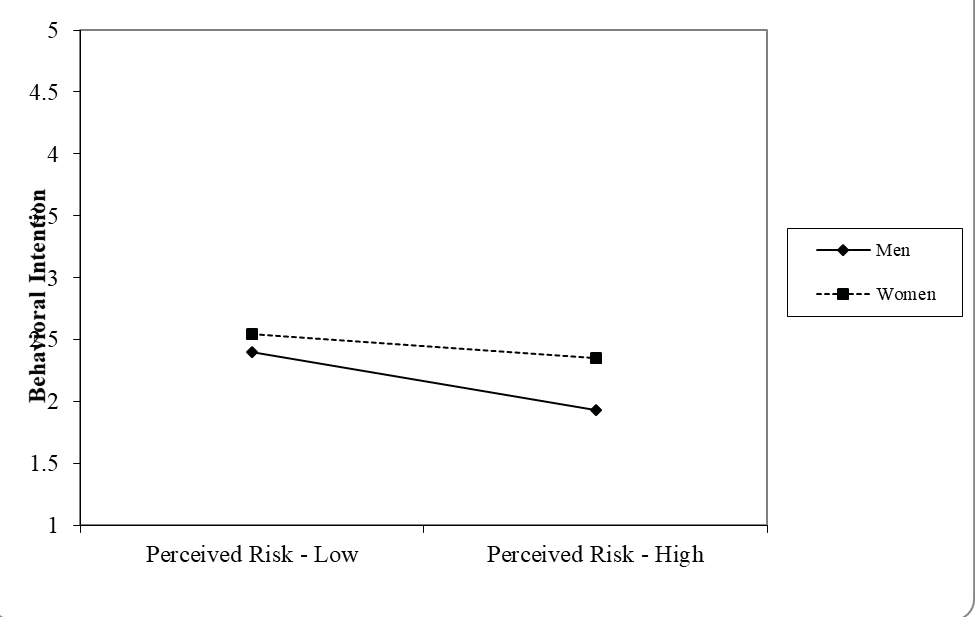

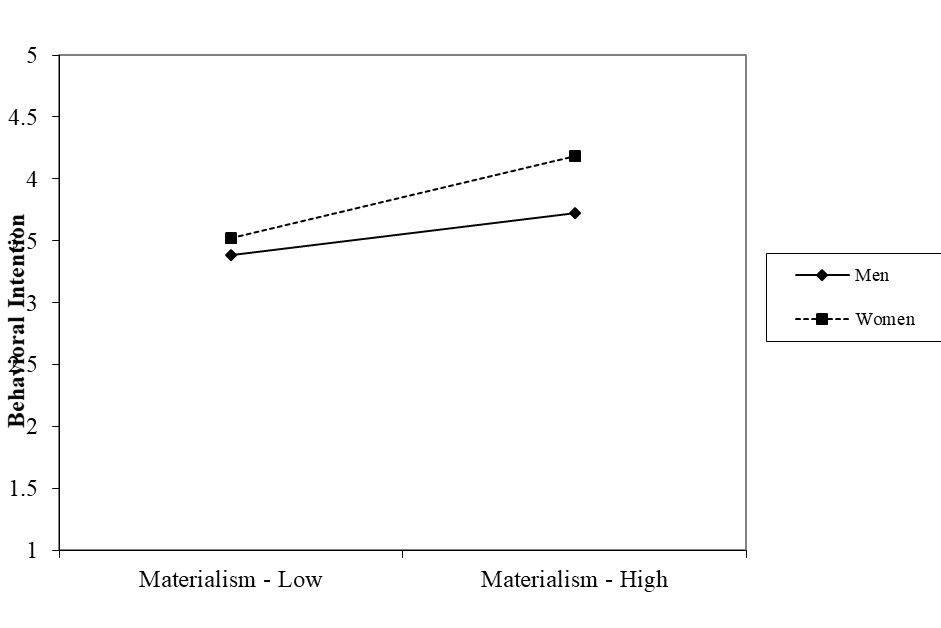

The visualization of moderation were presented in figures 3,,4,5 and 6.

Figure 3: Gender as a moderator in the relationship between desire and behavioral intention

Figure 4: Gender as a moderator in the relationship between frugality and behavioral intention

Figure 5: Gender as a moderator in the relationship between perceived risk and behavioral intention

Figure 6. Gender as a moderator in the relationship between Materialism and behavioral intention

As shown in Figure 2, at both low levels of desire, women are inclined to exhibit higher behavioral intention than men. Furthermore, when desire increases from low to high, the women tend to show higher behavioral intention than men. There is great divergence in the curves showing that women show higher behavioral intention to opt for shared accommodation. This graph renders support to H1a.

Figure 3 reveals the gender as a moderator in the relationship between frugality and behavioral intention. At the low levels of frugality women tend to show higher level of behavioral intention than men. At higher levels of frugality, however, men tend to show increased behavioral intention. As can be seen in the figure, when the frugality is low, women tend to show higher levels of behavioral intention compared to men. However, when frugality is high, men tend to show higher level of behavioral intention as compared to women. One plausible explanation is that women, as this study documented, tend to be more careful in

spending money when compared to men. High frugality suggests thinking twice before spending every single dollar. This graph

evidently suggest that gender differences are more prominent at different levels of frugality, thus supporting H2a.

As shown in Figure 4, at both low and high levels of perceived risk, behavioral intention for women is higher than that of males. Again, as the perceived risk increases, the women tend to show higher behavioral intention than males implying that women tend to take higher risks than men. This graph provides evidence in support of H3a.

Finally, the Figure 5 reveals that at both lower and higher levels of materialism, women tend to show higher behavioral intention than men. At the same time, as materialism increases, the rate of increase in behavioral intention was higher than men, thus supporting H4a.

DISCUSSION

The study represents a modest attempt to explore the antecedents of consumers’ intention to share accommodation. A conceptual model was developed and hypotheses were tested using Smart PLS-SEM.

The findings suggest that customers’ desire is positively associated with the behavioral intention to have sharing accommodation (hypothesis 1), which is in line with the studies from the literature (Yi et al., 2020; Yoo et al., 2017). The results support the strong positive relationship between frugality and behavioral intention (hypothesis 2), which is expected and obvious, especially considering the post-global pandemic. The perceived risk was negatively related to behavioral intention but not significant (hypothesis 3), contrary to the literature’s findings (Yuan et al., 2021). We probably speculate that one of the reasons for the insignificant relationship between perceived risk and behavioral intention is that the consumers had experienced health- related risks caused by the pandemic. Other travel-related risks might have been considered relatively low. Furthermore, people are frustrated with sticking to homes for extended periods, giving less weight to perceived risk. Similarly, contrary to the results from earlier studies, the positive association between materialism and behavioral intention (hypothesis 4) has been supported in this study. The latest research in tourism and hospitality found that the consumers’ behavior has altered significantly such that materialism is positively related to behavioral intention (Evers et al., 2018). The relationship between the behavioral intention of customers and their preference to adopt sharing accommodation has been supported in this study (hypothesis 5). This is consistent with the literature on sharing accommodation and sustainable consumption (Tsou et al., 2019).

This study found that gender significantly alters the relationship between the independent variables: desire, frugality, perceived risk, and materialism (hypotheses 1a – 4a). To the best of our knowledge, gender as a moderator in these relationships has not been studied, and hence cannot vouch for the results obtained from this study. However, most of the studies carried out earlier found significant gender differences in consumer behavior (Lee & Kim, 2017; Richard et al., 2010). The results from this study are in line with the reflections from the literature.

The results from this study have several theoretical implications for tourism and hospitality research. First, the conceptual model has taken MGB as a theoretical base instead of the TRA and TPB, which most earlier studies used. Since the behavioral intention towards sharing accommodation is not driven by emotions and environmental situations, this study argues that MGB is an appropriate theory to explain consumer behavior. This study, thus, extends the theoretical support offered by MGB. Second, the study found that customers’ desire leads to behavioral intention, though the reasons for each individual and family may be different. Though the authors did not study the black box of why and how desire results in behavioral intention, past research found that sustainable consumption and seeking a new tourism experience were the motivating factors (Mahadevan, 2018). Third, the results provide strong support for the intention to use shared accommodation which further leads to usage of shared accommodation, thus adding to the literature on tourism and hospitality research.

The fourth significant contribution of this study is the role gender played in the relationships between variables influencing behavioral intention. Most importantly, the results suggest that the desire of women to exhibit behavioral sense is more substantial than that of men. At the same time, the relationship between materialism and behavioral intention is more vital for women when compared to men. However, concerning frugality, men tend to show increased behavioral intention, whereas women tend to maintain the same level of behavioral intention irrespective of frugality. Finally, the adverse effect of perceived risk is more noticeable for women than men.

This study has several implications for the practitioners interested in promoting the sharing accommodation. First, customers’ intention to opt for sharing accommodation largely depends on the desire of the customers to have a unique and different experience of tourism. The present-day post-global pandemic situation created an excellent platform for the customers to share

accommodation, thereby utilizing scarce resources. Unlike traditional materialist consumers who prefer to own resources, the present-day customer who chooses to share accommodation needs to be recognized (Del Mar Alonso-Almeida et al., 2020). Second, in the financial crunch individuals and families are experiencing because of the global pandemic, frugality plays an essential role in opting for sharing accommodation. Consumers who believe that ‘a penny saved is a penny earned’ are more likely to opt for sharing accommodation, thus saving money and having different experiences of enjoying a vacation in various communities. Third, as this study found, in the decisions concerning the sharing accommodation, gender plays a vital role. In all, this study provides strong empirical evidence that a combination of factors leads to customers’ behavioral intention towards sharing accommodation.

This study is not without any limitations. First, the study focused on a limited number of variables. There could be a host of other variables that influence customers’ behavioral intention concerning sharing accommodation. For example, the level of trust customers on the information provided on websites about the sharing accommodation plays a significant role. Future researchers can address the influence of trust on the behavioral intention of sharing accommodation. Second, this study was conducted in a developing country, India. Future researchers can make cross-country comparisons, as done by earlier researchers (Davidson et al., 2018). Third, it would also be interesting to examine the comparison between developing nations to see the effect of variables selected in this study on sharing accommodation.

CONCLUSION

This study aimed to explain the factors leading to the behavioral intention of sharing accommodation from a developing country’s perspective. As the global pandemic has resulted in colossal losses to several organizations worldwide and nations are embarking on resilient strategies to bring normalcy, this study offers a simple model unfolding the factors contributing to the shared accommodation. Furthermore, with the gradual increase in the demand for domestic tourism and growing conscientiousness about sustainable consumption, it is hoped that sharing accommodation continues to be on the agenda for tourism and hospitality research.

REFERENCES

International Journal of Service Industry Management, 16(4), 357–372.https://doi.org/10.1108/09564230510614004

empirical approach. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 52, 101900.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2019.101900

American Journal of Health Behavior, 27(3), 208-218.https://doi.org/10.5993/AJHB.27.3.2

2001. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 15(2-3), 19-38.https://doi.org/10.1300/J073v15n02_02

the Emergency Situation of COVID-19 in Latvia. Frontiers in Psychology, 12.https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.682459

23(6), 515 – 534.https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20132

Characteristics. Journal Of Marketing Research, 38(1), 131–142.https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkr.38.1.131.18832 Obeidat, M., & Almatarney, A. (2020). Risk perceptions among potential Airbnb hosts. Éthique Et Économique, 17(2), 74-87.

Oh, H. (1999). Service quality, customer satisfaction, and customer value: A holistic perspective. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 18(1), 67- 82.https://doi.org/10.1016/S0278-4319(98)00047-4

Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 7(1), 21–34.https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.234

Ekonomska Istraživanja, 34(1), 2484-2505.https://doi.org/10.1080/1331677X.2020.1831943

factors. Research in Personnel and Human Resources Management, 13(1), 117–151.

Behavior. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research. 18(1), 311-332.https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer18010017

Please cite this article as: