Introduction

One of the biggest public health problems of the 21st century is the increase in childhood obesity. According to the World Health Organisation, obesity is defined as excessive fat accumulation that can lead to negative health consequences (WHO, 2018). One of the most common causes of obesity in children and adolescents is the imbalance between calorie intake and consumption. The most common factor contributing to obesity is the increased consumption of foods high in fat and sugar along with highly processed foods, the increase in portion size and the number of meals eaten daily, accompanied by high consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages, high-glycemic foods and reduced physical activity (Kumar and Kelly, 2017; Styne et al., 2017). Several studies have shown that the consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages has increased, while milk consumption has decreased over the last 20 years (Troiano et al., 2000; Nielsen and Popkin, 2004). It is now known that high consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages can lead to many chronic non-communicable diseases, including obesity or related obesity (Caprio, 2012), type 2 diabetes and cardiometabolic outcomes (Malik and Hu, 2019). Research indicates an inverse association between milk and other dairy products and obesity and obesity indicators in children (Dougkas et al., 2019), with most studies attributing this effect mainly to total milk consumption (Babio et al., 2022). It has also been found that lower milk consumption, which is an important source of calcium among other things, can lead to osteoporosis, especially in women (Dietz, 2006).

The European Society of Endocrinology as well as the Pediatric Endocrine Society guidelines and a Position Paper of the European Academy of Paediatrics and the European Childhood Obesity Group point out that the consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages should be limited and replaced by water (Styne et al., 2017; Dereń et al., 2019). It is also known that there is a negative correlation between bone health and the consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages, especially carbonated beverages (Ahn and Park, 2021). Parallel to the increased consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages, a significant increase in the consumption of sweetened fruit juices was recorded in the period from 2003 to 2010 (Kim et al., 2014). The American Academy of Paediatrics recommends that children should limit their consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages and juices, while overweight or obese children should consume them in small amounts or avoid them altogether (Heyman and Abrams, 2017). On the other hand, regular daily consumption of milk and dairy products has declined in many countries in recent decades (Dror and Allen, 2014). Regular daily milk consumption is associated with a lower risk of all-cause mortality, coronary heart disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes and bone health (Guo et al., 2022) and is a source of many important nutrients for growth and development, including calcium, vitamin D, high-quality protein and other nutrients. In terms of health benefits, most national guidelines recommend that the daily intake of milk and dairy products should be 2 to 3 servings (approximately 500 mL) for children up to 9 years of age and 3 to 5 servings (>600 mL) for adolescents (Dror and Allen, 2014). According to the meta-analysis by Doughkas et al. (2019), the current evidence that milk and dairy products can contribute to weight gain and increased appetite is still insufficient.

The aim of this study was to determine the effects of dietary intervention, which was carried out as part of a multidisciplinary structured programme, on reducing the consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages and sweetened fruit juices while increasing the consumption of milk and dairy products in overweight children/adolescents. This study will significantly contribute to the current knowledge of the relationship between changes in dietary habits and the impact on the development of obesity.

Materials and methods

Ethical statement

This study was conducted at the University Hospital Center Zagreb, Department of Paediatric Endocrinology and Diabetes, Department of Nutrition and Dietetics and at the University of Zagreb Faculty of Food Technology and Biotechnology, Croatia. The multidisciplinary structured programme included individual and group counselling in the areas of nutrition, endocrinology and psychosocial issues for children/adolescents and their parents/guardians and was conducted by a multidisciplinary team (endocrinologists, nurses, psychologists, social counsellors, physiotherapists and dieticians). The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University Hospital Centre Zagreb (No. 8.1–19/183–3–02/21AG; 19.07.2019) and was conducted in accordance with the conditions of the Helsinki Declaration. Before the start of the study, the parents/guardians signed a consent form for the participation of the children/adolescents in the structured programme, after being informed about all procedures and measures that will be performed during the study.

Study group

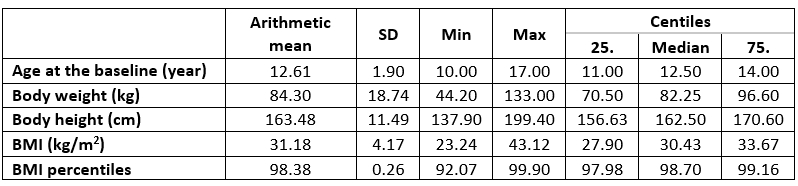

The study included a total of 100 participants (50 females), 50 were preadolescent age (10 to 12 years) and 50 of adolescent age (12 to 18 years), who were diagnosed with obesity and referred to Daily Hospital of the Department of Paediatric Endocrinology and Diabetes, University Hospital Centre Zagreb. Participants were included in the study if they met the inclusion criteria until the planned number of respondents was reached. Inclusion criteria were children/adolescents diagnosed with obesity according to body mass index (BMI) ≥ 95th percentile according to Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (Medscape, 1998-2011; CDC 2022; 2023) and who provided written informed consent from their parents/guardians. Exclusion criteria were children/adolescents younger than 10 years or older than 18 years at the start of the study; with endocrine (Cushing's syndrome, hypothyroidism, growth hormone deficiency, pseudohypoparathyroidism) or genetic causes of obesity (Prader-Willi syndrome, Laurence-Bardet-Biedl syndrome, Cohen syndrome, Alström syndrome); who were receiving pharmacological therapy for the treatment of obesity or therapy that can influence changes in body weight. In addition, all participants who could not adhere to the research protocol were excluded. The included participants were divided into age- adjusted groups in which a 6-hour daily education programme was conducted in the hospital with the aim of changing dietary and lifestyle habits. The mean baseline BMI was 31.18±4.18 kg/m2; the BMI percentile was 98.38±1.26; the mean consumption (±SD) of sugar-sweetened beverages at baseline was 1.68±2.89 dL per day; fruit juices 3.72±5.09 dL per day and milk and dairy products 3.10±2.35 dL per day.

Multidisciplinary structured programme

The multidisciplinary structured programme was conducted at the Department of Paediatric Endocrinology and Diabetes and the Department of Nutrition and Dietetics at the University Hospital Center Zagreb in Zagreb. The multidisciplinary team consisted of endocrinologists, nurses, psychologists, social counsellors, physiotherapists and dieticians. Participants with a diagnosis of obesity were recruited by an endocrinologist and admitted to the Daily hospital for obese children/adolescents. Participants were divided into age- appropriate groups (6 to 10 participants per group) for 6 hours per day as part of a five-day programme. A multidisciplinary, structured group programme was offered to both the children/adolescents and their parents/guardians, with a focus on dietary intervention. Education was provided to both, the children/adolescents and their parents/guardians together and separately, and individual education was also offered if required. After one week in the Daily hospital, the children/adolescents and their parents/guardians were invited once a month for the first 6 months for follow-up examinations with re-education and anthropometric measurements. Over the next year and a half until the end of the study, follow-up examinations took place every 2 months. Biochemical measurements were taken at the beginning of the study and than every 6 months until the end of the study.

Dietary intervention

The dietary intervention was based on education about healthy eating habits: emphasising the importance of regular meals, especially meals eaten at home, and the number of meals eaten out, especially at fast food restaurants, reducing processed foods high in fat and sugar (e.g., sweets and snacks), reducing the consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages and fruit juices. In addition, the intervention focused on improving dietary habits, such as increasing the consumption of fruits and vegetables (5 servings per day) and milk and dairy products (3 servings per day, 1 serving = 200 mL) according to the guidelines (MZ, 2013; Styne et al., 2017). During the five-day intervention programme, participants received meals (2 of 3 main courses and a snack), breakfast and lunch, and fruit as a snack as an additional educational measure according to the Mediterranean reduction diet based on the Decision on the Standard for Nutrition of Patients in Hospitals (Odluka, 2015), National Guidelines for the Nutrition of Students in Primary Schools (MZ, 2013) and in accordance with the guidelines of the European Society of Endocrinology and the European Society of Paediatric Endocrinology (Styne et al., 2017) and the American Academy of Paediatrics (Barlow et al., 2007). Assessment of risk factors related to dietary habits and physical activity were assessed using a questionnaire and validated questions (NHMRC, 2003; Flood et al., 2005) at baseline, 12 and 24 months after baseline and at each dietary change follow-up visit.

Variables analysed

Anthropometric measurements were taken by a nutritionist at the beginning of the study and at each follow-up visit. This included measuring body weight on a calibrated digital scale with an accuracy of ± 0.1 kg (Omron Karada Scan) and measuring height on a stadiometer with an accuracy of ± 0.5 cm (Seca, 0123, Portable stadiometer). Body mass index was calculated using the Quetelet index (body weight (kg)/body height squared (m2) and estimated using CDC percentile curves (Medscape, 1998-2011; CDC 2022; 2023). Successful weight loss was defined using BMI percentiles. The effect of the dietary intervention on the consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages, fruit juices and milk and dairy products were assessed using validated questions that were answered at baseline, 12 months and 24 months. The questions required quantitative data on the amount of sugar-sweetened beverages, fruit juices and milk and dairy products consumed (NHMRC, 2003; Flood et al., 2005).

Results and discussion

The initial data of the study group are shown in Table 1. Of the initial 100 subjects, 92 participants were included after 6 months, 75 participants after 12 months and 62 participants after 24 months (62 % of respondents completed the entire study). Previous studies were conducted with a similar structure and objectives, involved a multidisciplinary intervention and were conducted over a total duration of 6 to 24 months, with 41 to 209 subjects enrolled and 31.0-76.6 % of respondents completing the study (Coppins et al, 2011; Lison et al., 2012; Brennan et al., 2013; Lochrie et al., 2013; Boodoai et al., 2014; Rijks et al., 2015; Serra-Paja et al., 2015; Gow et al., 2016; Ranucci et al., 2017; Ojeda-Rodriguez et al., 2018; Albayak et al., 2019).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of study group

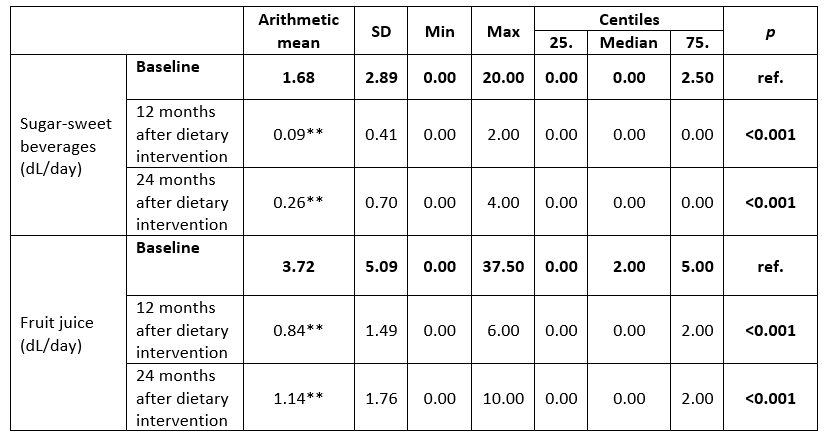

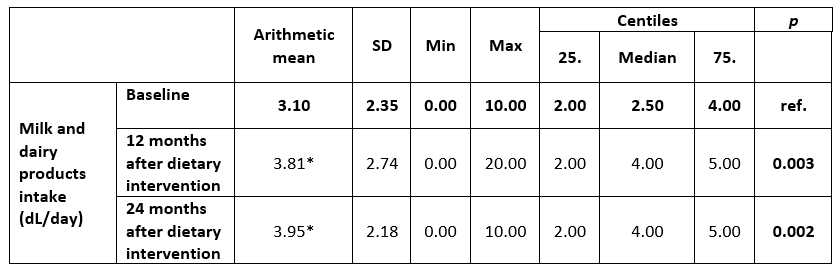

With regard to the problem of obesity in children and the poor dietary habits that can further aggravate the condition, changes in consumption habits of sugar-sweetened beverages, fruit juices and milk and dairy products were observed during the course of the study, probably due to the intervention carried out (Table 2 and 3). Previous studies have shown an inverse relationship between the consumption of sweetened beverages and milk as well as between the consumption of milk and obesity in children (Mirmiran et al., 2005). Also, milk and dairy products are nutrient rich and make a significant contribution to Ca, iodine, riboflavin, vitamin B12, K and vitamin A intakes in children. Considering that it should be determined whether a nutritional intervention would show the effect of improving milk intake at the expense of consumption of carbonated and sweetened beverages along with a loss of body mass.

Table 2. Differences in sugar-sweetened beverages intake during study

ref.= reference variable, Wilcoxon test, **p<0.001

In this study, a significant decrease (p<0.001) in the consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages was observed after 12 and 24 months. After 12 months, consumption decreased by 1.59 dL, and after 24 months by 1.42 dL compared to the baseline value of the study (Table 2).

A significant decrease (p<0.001) in the consumption of fruit juices was also observed in this study after 12 and 24 months. After 12 months, consumption decreased by 2.88 dL, and after 24 months by 2.58 dL compared to the baseline value of the study (Table 2). According to Reinehr (2013), one of the most important intervention goals in programmes for children and adolescents is to reduce the consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages. Related to this research, a 2-year follow-up study of 224 obese adolescents found no significant decrease in fruit juice consumption between the intervention and control groups (-3.00±17.00, p=0.44) (Ebbeling et al., 2012), as did Brennan et al. (2013) at 6 months follow-up (p=0.056). According to Serra-Paya, the group that received a multidisciplinary, family-based, bihevioral intervention had a significant decrease in daily consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages (p<0.047) compared to the group that received only paediatric counselling at the 8-month follow-up (Serra-Paya et al., 2015).

Table 3. Differences in milk and dairy products during study

ref.= reference variable, Wilcoxon test, *p<0.05,

In this study, a significant increase in the consumption of milk and dairy products was observed after 12 months (p=0.003) and 24 months (p=0.002) (Table 3). At baseline, the median intake was 2.5 (2.0-4.0) and after 12 and 24 months it was 4.0 (2.0-5.0). These results suggest that individual participants adhered to the recommendations for daily intake of milk and dairy products, in contrast to some previous studies that found no differences in intake at 6 months (p=0.99) (Brennan et al., 2013) and at 12 months (Pakpour et al., 2015), but consistent with Keller et al. (2009) where sweetened beverage intake was negatively correlated with both milk (p<0.01) and calcium (p<0.01) intake.

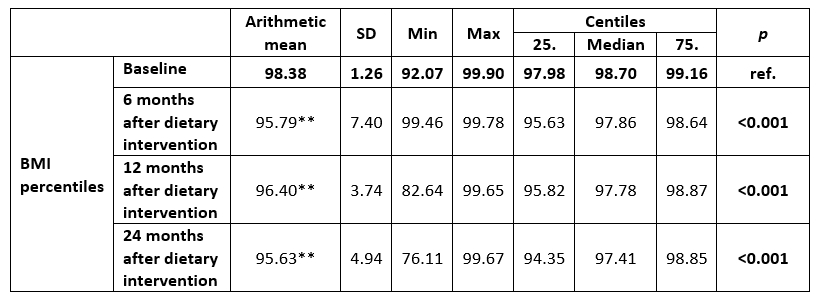

Table 4. Differences in body mass index (BMI) percentiles during study

ref.= reference variable, Wilcoxon test, **p<0.001

A significant decrease in BMI was observed 6 and 12 months after the start of the study (p<0.001) and an increase after 24 months. However, as children/adolescents are still growing intensively during this period, BMI percentiles were used as a better predictor of change as they are adjusted for age (Styne et al., 2017), and a significant decrease in BMI percentiles was found throughout the observation period at 6, 12 and 24 months (p<0.001). BMI could be a significant indicator of milk and dairy product consumption, as studies have shown a significant inverse correlation between BMI and daily milk consumption (r=-0.38, p<0.05) (Mirmiran et al., 2005), which could also be related to the results of this study, in which the children who had a significantly lower BMI after the intervention, had a significantly higher consumption of milk and dairy products.

Conclusion

A dietary intervention with long-term follow-up as part of a multidisciplinary structured programme has a positive effect on reducing the daily consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages and fruit juices, which are one of the factors that can lead to a reduction in BMI percentiles, and contributes to regular consumption of milk and dairy products in line with recommendations.

References

WHO-World Health Organization (2024): Obesity and overweight, World Health Organization, <https://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/childhood/en/>. Accessed 29. March 2024.