1. INTRODUCTION

Hotel services obtain high fixed costs with long term returns on investment and its role is to earn much revenue to pay for its perishable nature. There was 70% of the hotels in Vietnam (VN) applied digital technology into their venues, compared to 50% in 2015 due to 48 out of 72% of the online users searching for hotel destinations (Vietnamnews 2018). The online travel booking for the hotel in VN contributed $493mil in a total of US$671mil including package holidays and private vacation rentals (Statistica, 2018). The occupancy (OCC) rates in 5-star hotels consumed from 64% to 100% and average room rate (ARR) differed from $151 to $451/room/night, the growth of 4-star hotels in both of OCC rates and ARR got 87% and $127/room/night respectively (Colliers 2017). The main income of luxury hotels in VN was earned by room revenue at 60% of hotel revenue (Grant Thornton 2018). The international and domestic tourists in VN in 2018 reached 15.5 million and 80 million, up 2.7 and 6.8 million compared to 2017 respectively (Koushan 2019). PATA forecasted that VN is predicted to lead Asia Pacific destinations regarding its average annual growth rate from 2019-2023 at 15.5 million and in 2018 Chinese arrivals (23.9%) were a majority for the gaming industry as a demand generator (PATA 2019).

The advanced internet changes customer behaviors in online purchasing tourism-related products. Regardless of the hotel rating, based on hotel’ pricing fairness and room rate management to different users in various booking channels (i.e. web-based hotel, online travel agencies (OTAs), etc.), in turn, increase customers’ loyalty intention from their insight and for future use. So room rate strategy is required to maximize profit and customer satisfaction levels due to prospective customers are inclined to search for best hotel deals from online purchases before 20-30 days (Sun, Law, Schuckert and Fong 2015) to the last-minute booking (Yang and Leung 2018). But on the luxury market, the direct online channels (i.e. hotel website, sale representative) were cheaper than the economy, mid-priced properties, GDS and OTAs (O’Connor 2002). Besides, upper-scale hotels practiced opaque discount selling based on the hotel class, operation mode, market structure and online reputation (Yang, Jiang and Schwartz 2019). The pricing decisions reemerged as a key concern for hoteliers including customers’ experience and competition on hotel pricing in different countries (Manuel, María and Sergio 2019). Therefore, the competitive pricing strategy positively influenced on revenue per available room and the volume of hotel rooms available in the market (Chiang, Lin, Chi and Wu 2016). In order to build up customer relationship or customer loyalty intention to the hotel brand, it is imperative for management to handle marketing strategy effectively. The factors affecting customer satisfaction behinds the rating on Trip advisors found that hotel performance towards customer satisfaction evaluation has significant interaction with visitors’ characteristics including nationality, highly characteristic destination (Radojevic, Stanisic and Stanic 2017). While loyalty intention between customers and the company is a core value to enhance the venue’s profitability. Loyalty intention and brand attachment were influenced by communication-based and value-based fairness (Hwang, Baloglu and Tanford 2019). In China market, hotels and online agencies competed each other through the method of cashback after stay in order to retain and regain customer booking intention (Guo, Zheng, Ling and Yang 2014) and ensure the brand development (Ye, Barreda, Okumus and Nusair 2017) for loyalty and sustainable progress especially on luxury hotels (Liua, Wong, Tseng, Chang and Phau 2017).

In recent years it is no longer uncommon idea when many venues opt to live on their room rate strategy, particularly hotels locate in large cities all around the world. We tend to believe the rise in the progress of hotel room rate management is a positive one to upgrade customer satisfaction and CEBs. It is the main cause of the study. Undoubtedly, there could be some negative aspects. Customers who experience feelings of unfair pricing if any. They miss out on the emotional support that hoteliers can provide and they must bear the weight of all dynamic room rates and loyalty intention. All of these would result in heavier pressure on them. However, there could be more positives when hotels practice suitable room rate strategy. The rise in dynamic room rates can be seen as desirable for both personal and broader economic reasons. On the individual level, customers who choose to pay different prices on different conditions in a certain period may become more independent to accept the room rates are offered by the hotel. For instance, the effect of hotel revenue management on 5-star hotels in Barcelona (Algeciras and Ballestero 2017) or the effect of quality-signaling factors on the market accessibility and hotel prices in the Caribbean (Yang, Mueller and Croes 2016). From an economic perspective, the trend towards dynamic room rates for various distribution channels will result in a greater demand for travelers. This is likely to benefit the tourism industry, OTAs and a whole host of other companies that rely on hotel owners to buy their products or services. For example, the cross channel disparities in U.S lodging markets (Yang and Leung 2018) or the competitive price interactions in Houston hotel market (Kim, Lee and Roehl 2018).

To bridge the research gaps, the present empirical study aims to heighten the level of customer satisfaction level, CEBs and expect to predict the mediating role of customer satisfaction towards the service quality of customers’ perception of room rate strategy on the luxury hotels (from 4-star to 5-star hotels) in VN. Because it leads to more beneficial effects on individual and on the hotel revenue performance. This study is one of 319 valid respondents have been collected by online and offline survey to measure customers’ idea then used PLS-SEM to measure and test the items. Especially, this study expects to contribute to the hotel literature on room rate strategy, which is filled by very little previous literature in the tourism market. From a practitioners’ perspective, the findings may help hotel revenue managers to increase service performance, customer satisfaction and engagement attitudes based on effective and efficient room rate strategy.

2. LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1. Customer cognition of hotel room rate strategy

The paper studies how the customer perception of hotel room rates impacts customer satisfaction and CEBs regarding luxury hotels in Vietnam tourism market. The expected factors that recognize customer cognition of hotel room rates in this study are price fairness, revenue management and loyalty intention.

There has been a noticeable trend towards hotel room rate fairness becoming lucrative for traveling users and many companies have made their involvement in this industry. This development is both positive and negative for the advancement of tourism. In marketing, the price considered as a “fair” charge for the product (Bolton, Warlop and Alba 2003) and it was expected by previous information of memory of customers (Mazumdar, Raj and Sinha 2005). The most glaring merit for price fairness from service providers is top-notch to enhance users’ satisfaction. It is quite true that featuring branded service endorsements is a popular source of income for hotels at their peak performance. Because price transparency could reduce the guest's perceptions of pricing unfairness (Ferguson 2014). This financial motivation can enable users to exert their choices by booking more rooms and maintaining as repeated guests with their familiar hotels consistently in any stay. If most customers were financially motivated, room rate fairness, in general, could benefit from more benefit to utilize hotel value and quality towards price ending strategy (Collins and Parsa 2006). This has not only affected on guests’ willingness to buy product/services (Ferguson 2014) but also cultivated their sense of financial condition such as costs, demand, competition and distribution channels (Xia et al. 2004); or price war among hotels which changes the room rates at the same time (Viglia, Mauri and Carricano 2016); or optional product pricing and promotional pricing (Nair 2018). As far as a corporation is concerned, an online distribution channel with OTAs in this industry can take pricing strategy of the hotel. By promoting the lower prices demonstrating the most familiar marketing channels, the businesses were likely inclined to achieve more profit and set a high expectation among the public (Ling, Guo and Yang 2014). If the below 3-star hotels happened to show a slight decline in uniform pricing, but higher quality hotels such as above 4-star hotels (Melis and Piga 2017), customers would not hesitate to voice their frustration and disapproval, affecting the overall quality of service. Therefore the customers’ willingness for hotel room rates should count in the previous day’s prices (Solera, Gemar, Correia and Serra 2019). Consequently, if consumers who perceived unfair prices would show a greater sense of negative CEBs towards the providers (Xia et al. 2004). Meanwhile, other potential benefits of room rate fairness are not invested in, which is a huge waste.

The different room rates are utilized in different markets by hotel management named revenue management (RM). These rates significantly impact a hotel’s profit through room sales. Hotel news now generated room sales included cooperating with 3rd party (e.g OTAs, travel agencies, GDS) occurs commission fee which causes a higher room rate charged to the consumer; selling rooms for business group with negotiated room rates (lower rates than rack rates or publish rates); accommodating for walk-in guests can earn much profit with highest room rate (Hotel news now 2018). A study on the occupancy rates of 346 hotels located in Rome through regression analysis the impact of consumer reviews confirmed that the occupancy rate increases 7.5 percentage points by a one-point increase in the review score (Viglia, Minazzi and Buhalis 2016). The authors also suggested that in the short-run price variations, the online reputation earns a higher important role over the traditional star rating (Abrate and Viglia 2016). For example,Nicolau and Sellers (2019) studied in the context of price responsiveness and service bundling between flight and accommodation, an individual books one service independently of another. They proposed that customers who find a price higher than expected are more willing to take it if the product is included in a package (Nicolau and Sellers 2019). Therefore, the room rates could be changed simultaneously in all channels (Algeciras and Ballestero 2017) and enhanced competitive advantages in lodging business (Nair 2018). To begin with, the hotel revenue managers/owners offer perishable service products. This has enabled them to the most profitable mix of customers, thus optimized them to release vacant rooms and increase hotel revenue (Algeciras and Ballestero 2017). As regard users, it can be argued that price-sensitive customers who are willing to purchase at off times can do so at favorable prices, as opposed to those insensitive customers who want to purchase at peak times, will be able to do so at higher prices than normal times (Kimes and Wirtz 2013). This is because updated information is subject to the rooms' availabilities and the discounted room rates are always available for a review of pre-established requirements (Algeciras and Ballestero 2017). There is much need for hoteliers to allocate appropriate revenue management towards the different market target in certain scenarios which are a beneficial effect on hotels and customers.

It is argued that customer loyalty intention is primarily attended by tourists in marketing. One of the reasons is that room booking intention is the willingness and tendency of one to participate in trading (Ferguson 2014). As newcomers to another hotel, users show a greater sense of curiosity about the facility and service, thus feel strongly motivated to discover the venue. The potential customers are involved with hotels via a peer-to-peer communication channel such as TripAdvisor, Facebook, etc. (Liua, Lee, Liu and Chen 2018). To be more precise, many luxury hotels do not come cheap, appear in visual elegant design and often require a substantial amount of service fee which is less affordable for most customers from local to foreign countries. As for hotel revenue management, improper application of revenue management principles should be avoided to seed stereotypical judgments into people’ thinking, resulting in social disorder and chaos to build consumer intention for loyalty (Algeciras and Ballestero 2017) and lead to healthy influenced reputation (Guo, Zheng, Ling and Yang 2014) or offer offline room rates comparable to the expected last-minute prices (Guizzardi, Pons and Ranieri 2017).

2.2. Customer satisfaction

It is as understandable as to why customer satisfaction out to be prioritized and one of the reasons is that customers perceive service quality of hotel standard (Li, Ye and Law 2013) on a great deal of quality time, resulting in better profit or performance productivity (Gavilan, Avello and Navarro 2018). For instance, the introduction of good service quality would help customers have more time relaxing if they are on the vacation or enable them to complete their outstanding tasks away from the office for a business trip (Hung 2017). Another merit worth mentioning is that a higher satisfaction level means an increase in the numbers of users to be provided (Napaporn, Aussadavut and Youji 2016). This could result in a rise in the income obtained from more rooms sold which could be allocated to the development of a hotel in overall. But, those who maintain aspects of guest satisfaction via service quality are critically important and should be prioritized could certain justifications. The service quality was measured in practice but less adequate assess especially in poor hotel achievement. This is a lack of support from operation staff who are obliged to rely on themselves when it comes to resolving problems. The incentives are in place to encourage reservation and front office staff to up-sell and cross-sell (Cetina, Demirciftci and Bilgihan 2016). Sustainability of customer satisfaction has been in the light recently has become a pressing issue on service performance itself in order to meet customer’s expectations (Napaporn, Aussadavut and Youji 2016) (Zhao, Xu and Wang 2018). The booking intention involved the evaluation of service quality and customer satisfaction (González, Comesaña and Brea 2007). By concentrating customer satisfaction on research and development of tools to measure the service quality on the satisfaction of hotels RRS (Tabaku 2016), the authorities could help lessen the impact of disruptions from unattended hoteliers in operation and room rate practice (e.g. Full-service hotels may track 10 to 20 different market segments in the transient and group markets (Steed and Gu 2005)). Therefore our hypothesis suggests a relationship between service quality and customer satisfaction towards customer perception of hotel RRS:

H1: The higher service quality, the higher customer satisfaction will be

2.3. Consumer engagement behaviors (CEBs)

CEBs’ perception is “go beyond transactions and may be specifically defined as a customer’s behavioral manifestations that have a brand or firm focus, beyond purchase, resulting from motivational drivers” (Doorn et al. 2010). In hotel and tourism research, the utilization of CEBs is preferable as ‘‘a psychological state, which occurs by virtue of interactive customer experiences with a focal agent/object within specific service relationships’’ (Brodie, Hollebeek, Juric and Ilic 2011). Previous authors studied factors affecting customer satisfaction behinds the rating on Trip advisors found that hotel performance towards customer satisfaction evaluation has significant interaction with visitors’ characteristics including nationality, highly characteristic destination (Radojevic, Stanisic and Stanic 2017). Sometimes, customers prefer positive CEBs’ evaluations more than negative (Wei 2013). However, in our opinions, some certain cases, the function of CEBs is nearly impossible to replace. The boom in the marketing and corporate performance in today’s interactive and dynamic business environments meant that we have to know CEBs as there can be vital to attract, purchase/repurchase and even more effective for greater loyalty to focal brands (Hollebeek 2010). For instance, customers would complain about the different rates due to discount policy of hotel (Hanks, Cross and Noland 2002) and require the hotel management's explanation (Choi and Mattila 2004) or even would say things negatively about the hotel’s rate policy to other customers (Price, Arnould and Deibler 1995). To be more precise, CEBs have had a great source of changes in the firm’s policies after customer's voices (i.e. apologize and/or a refund after a complaint behavior) which can be improvements in the products or services (Doorn et al. 2010). On the luxurious service,Yang and Mattila (2016a) used a survey questionnaire to test the 04 luxury restaurants and confirmed that a consumer engagement attitude for purchase intention is influenced primarily by its value, function, and finance (Yang and Mattila 2016a). They additionally examined the combined effects of customer perception in hospitality services on word-of-mouth intentions (Yang and Mattila 2016b). The authors also suggested for further investigation the connection between luxury hotels and customer purchase intentions in which customers prefer for their happiness and hotels wish to position their brands/products. Besides,Nicolau et al. (2019) reported that the decision making of customers is based on the different choices individually (Nicolau, Losada, Alén and Domínguez 2019). As one of the early attempts, the present study explored one particular manifestation of CEBs in the hospitality setting: RRS of hotel industry. Hence, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H2: The higher service quality, the higher CEBs will be

H3: The higher customer satisfaction, the higher CEBs will be

In conclusion, setting the hotel room rate strategy maybe simply for being socially acceptable and our view is that this kind of management is mostly not detrimental to every single individual involved and venues. In this case, we test the impact of customer cognition of hotel room rate strategy on satisfaction and CEBs then examine the mediating effect of customer satisfaction between service quality and CEBs.

CONCLUSIONS

Based on theoretical views on management, this research creates a framework being that is the source of different organizational performance results and that has 2 main factors: (1) dynamic capabilities and (2) the HPO. This framework indicates that dynamic capabilities significantly impact organizational performance because they help to enhance the HPO and further heighten organizational performance. Nevertheless, it is also interesting to discover that the dynamic capabilities of independent hotels located on Samui Island at a lower level than those of chain hotels, which results in fewer competitive advantages. Thus, the management of these independent hotels must recognize and pay more attention to the creation of dynamic capabilities to enhance the HPO and organizational performance.

Limitations and future research directions

In conducting this study, there were some limitations, as the sample group employed in this research was limited only to hotel businesses on Samui Island, the main tourist attraction in southern Thailand, instead of the hotel businesses in all global tourist attraction sites in Thailand. Thus, the findings might also be limited with respect to their implementation in a broader environment. Future research is expected to cover other regions in Thailand or other global venues to obtain more universal findings that can be broadly implemented. In addition, future studies may measure performance by including real financial and nonfinancial outcomes to confirm the results and by using subjective measures.

3. METHODOLOGY

A field survey was achieved to support the stated research objectives. The three sections within a questionnaire was developed and requested from 5 – 10 minutes to complete the answers. Only those respondents who have stayed in venues from 4 to 5-star hotels within Vietnam were qualified to participate in this study to recall their experiences (Law and Hsu 2006), to imply customers’ understanding, exciting and potential needs (Law and Leung 2000).

First, the scenario was that “Assume you are coming to Vietnam to attend the seminar, and book a one-night stay at a luxury ABC hotel. During the break, you have the opportunity to talk with friends in the same workshop. At this time all three know that they are close to each other, the same room standard, the service is the same, except for room rates. Friend A came directly to the hotel and rented room at US$ 300 per night, while friend B booked online at the OTA website (Agoda.com) 6 days before arrival is US$ 250 per night, and you booked online at the website of the ABC Hotel 8 days before arrival and the price of $280 / night.”.

The assumed booking channels were different. They were from a 3rd party - OTA website, hotel website and directly walk-in to the hotel. The respondents were asked about their awareness in those differing views based on different booking channels and different booking time at 87.4%.

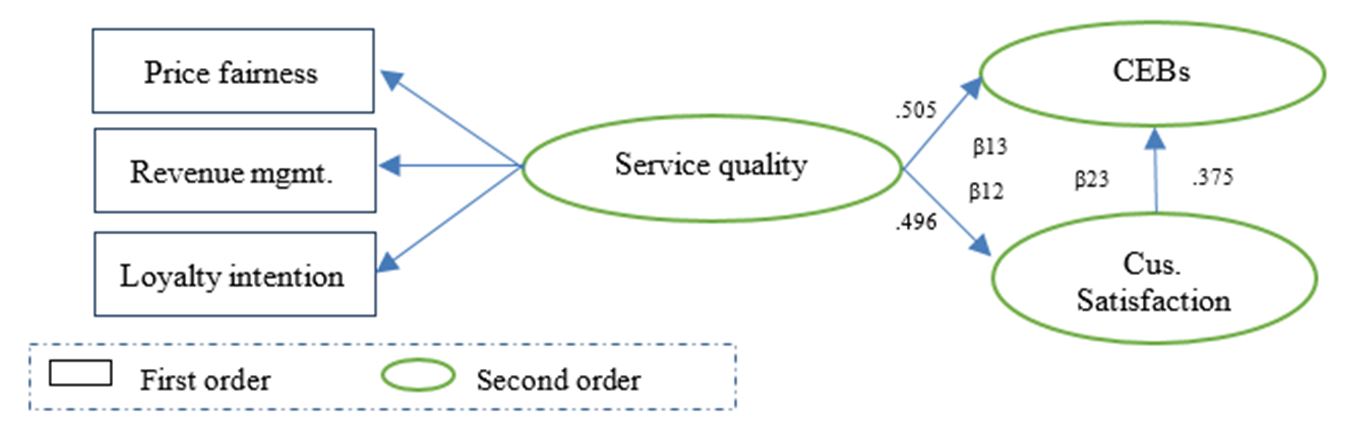

The 2nd section measured the respondents’ agreements of service quality, customer satisfaction and CEBs towards indicators of room rate strategies set by hotels. The constructs of measurements followed previous studies in literature review section closely. It should be noted that all 1st-order constructs have a reflective measurement, where the indicators are considered to be functions of the latent construct (Hair, Sarstedt, Ringle and Mena 2012). The 2nd-order constructs (perceived hotel service quality, CEBs and customer satisfaction) have a formative measurement due to the 1st-order variables are assumed to cause the 2nd-order variables (Jarvis, MacKenzie and Podsakoff 2003).

All 23 items with 6 variable attributes were measured on 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) to expand the number of choices among perceived agreement levels. The last section collected the respondents’ demographics such as gender, age, internet usages daily, education background, continents, personal income, and experiences, etc. The quantitative data were adapted from primary studies to reinforce the structure of questionnaire (table 1).

| Code | Statements | Key references |

| Price fairness | ||

| PF1 | A price effects on guest perceptions of pricing fairness | (Ferguson 2014) |

| PF2 | A price effects on willingness to purchase of guest | |

| PF3 | Consumers who perceive a price as unfair experience would occur negative attitudes toward the provider | (Xia et al. 2004) |

| PF4 | Costs, demand, competition and distribution channels are taken into consideration in pricing | |

| Revenue Management | Key references | |

| RM1 | The revenue management refers to selling perishable service products to the most profitable mix of customers (i.e. rooms at the hotel) to maximize hotel revenue | (Algeciras and Ballestero 2017) |

| RM2 | The pricing according to predicted demand levels so that price-sensitive customers who are willing to purchase at off times can do so at favourable prices | (Kimes and Wirtz 2013) |

| RM3 | The pricing according to predicted demand levels so that price insensitive customers who want to purchase at peak times, will be able to do so at higher prices than normal times | |

| RM4 | The discounted room rates are subject to compliance with pre-established requirements | (Algeciras and Ballestero 2017) |

| RM5 | The updated information is at hand on the number of rooms available | |

| RM6 | Room rates can be changed simultaneously in all channels | |

| Loyalty Intention | Key references | |

| LI1 | The room booking intention is the willingness and tendency of one to participate in trading | (Ferguson 2014) |

| LI2 | The hoteliers can offer offline room rates comparable to the expected last-minute prices | (Guizzardi, Pons and Ranieri 2017) |

| LI3 | Improper application of Revenue Management principles might negatively impact consumer intention for loyalty | (Algeciras and Ballestero 2017) |

| Service Quality | Key references | |

| SQ1 | Incentives are in place to encourage reservation and front office staff to up-sell and cross-sell | (Cetina, Demirciftci and Bilgihan 2016) |

| SQ2 | The booking intention involves the evaluation of service quality | (González, Comesaña and Brea 2007) |

| SQ3 | The booking intention involves the evaluation of product information | (Kerstetter and Cho 2004) |

| SQ4 | Different room rates are applied to different market segments | (Steed and Gu 2005) |

| Customer Engagement Behaviors | Key references | |

| CEB1 | I would complain about the different rates and require the hotel management's explanation | (Hanks, Cross and Noland 2002), (Choi and Mattila 2004) |

| CEB2 | I would switch to hotel’s competitor if I experienced with unfair prices | (Keaveney 1995), (Voss, Parasuraman and Grewal 1998) |

| CEB3 | I would say things negatively about the hotel’s rate policy to other customers | (Price, Arnould and Deibler 1995) |

| Customer Satisfaction | Key references | |

| CS1 | I am satisfied with the hotel room rate strategy | (Bilgihan, Barreda, Okumus and Nusair 2016) |

| CS2 | I would keep bookings the room with the hotel’ price policy | (González, Comesaña and Brea 2007) |

| CS3 | I would expect the offline or direct rates from hotel in the future | (Yang and Leung 2018) |

The questionnaire delivered to international and domestic respondents via online (links spread on the Facebook account and e-mail invitation) and face-to-face. It stratified the samples who experienced hotels from 4 and 5 stars standards within VN. The questionnaire was available in Vietnamese and English with its URL link for different respondents. Minor revision was modified with a Pilot test (n=59) to assess the consistency of constructs. A total of 400 replies with the response rate was 93% from Sept to Dec 2018. The excluded samples were incomplete surveys or answered with all ‘strongly agree/disagree’ in the questionnaire.

Females are the majority at 61.4% of the profile of respondents. The respondents tend to be mature about 70% from 25 to 45 years old, over 80% of them surf the internet over 4 hours daily and well educated from Bachelor to Postgraduate degree. So their monthly income is over 76% from above $1000 to $5000 reasonable to prefer service on luxury hotels. In this study, Asian respondents are the main representative samples, followed by American, Australian, European and African (72.6%, 13.1%, 6.2%, 4.7%, and 3.4% respectively). According to the Vietnam Investment Review, in the 1st half-year of 2018, Chinese tourists accounted for the majority (4.1 million) among the 7.9 million foreign tourists to VN. Over 92% of tourists stayed overnight, 7% visited the country for one day and more than 60 % organized their trips by (Vietnam Investment Review 2018). Up to June 30, 2021 tourists from Europe such as the UK, France, Germany, Spain, and Italy will enjoy visa exemptions when traveling to VN (Vietnam Investment Review 2018). The policy would promise to boost the European tourists to make their coming destinations in Vietnam in the future.

The common method variance (CMV) was approached to conduct data from the single source and based on Harman’s one-factor test (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee and Podsakoff 2003) to minimize the error terms. The cumulative percentage of total variance was explained 34.374% and KMO is 0.889 (Little’s MCAR test: chi-square = 2618.338, df = 190, significance = 0.00). Consequently, the CMV was not an issue and missing data was at random, not a serious threat to the dataset this study. The PLS version 3.0 was used for data analysis and testing. This tool estimated the path coefficients within models and turned to popular in tourism research recently (Nunkoo, Ramkissoon and Gursoy 2013) because of its applicable for latent constructs under conditions of non-normality from small to medium sample size (Hair, Hult, Ringle and Sarstedt 2013) and increase more inside it (Ringle and Sarstedt 2016). PLS algorithms were run to measure loading levels, weights, path coefficients and followed by bootstrapping (5000 re-samples) to determine the significance levels of the proposed hypotheses

4. RESULTS & DISCUSSIONS

4.1. Measurement model

According toHair et al. (2013), the measurement model was tested for convergent validity. This was assessed through factor loadings, composite reliability (CR) and average variance extracted (AVE). All item loadings recommended a value of close to 0.7 as shown intable 2 and accepted (Hair, Hult, Ringle and Sarstedt 2013). CR and AVE values were retained with the recommended value of 0.7 and 0.5 respectively which can indicate the latent constructs.

Table 3 shows the discriminant validity. The Fornell-Larcker criterion shows that the square root of each AVE (shown on the diagonal) is greater than the related inter-construct correlations in the construct correlation matrix indicating adequate discriminant validity for all of the reflective constructs. It also presents the heterotrait-monotrait ratio of correlations (Henseler, Ringle and Sarstedt 2015) as a better means to access discriminant validity.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| 1. CEB | 0.82 | |||||

| 2. LI | 0.398 | 0.847 | ||||

| 3. CS | 0.388 | 0.335 | 0.816 | |||

| 4. PF | 0.389 | 0.427 | 0.459 | 0.804 | ||

| 5. RM | 0.573 | 0.419 | 0.363 | 0.383 | 0.734 | |

| 6. SQ | 0.518 | 0.401 | 0.499 | 0.424 | 0.415 | 0.789 |

Table 4 indicates the weights of the 1st-order constructs on the designated 2nd-order construct. The results depict that hotel service quality is a 2nd-order construct with three significant positive 1st-order dimensions included customer perception of hotel room rate strategy. To be more effective, the price fairness variable is the highest impact on the hotel room rate strategy.

| 2nd-order construct | 1st-order constructs | Weight | T Statistics | P Values |

| Service quality | Loyalty Intention | 19.4 | 3.379 | 0.001 |

| Price fairness | 25 | 4.332 | 0 | |

| Revenue management | 23.8 | 4.097 | 0 |

4.2. Structural model

A bootstrapping procedure with 5000 iterations was used to test the structural model and hypotheses to examine the statistical significance of the path coefficients (Chin, Peterson and Brown 2008). In addition, PLS does not require to generate goodness-of-fit indices.

Thefig.1 results in the structural model of 2nd-order constructs. The corrected R2 values show the explanatory power of the predictor variables on the respective constructs. Hotel service quality predicts 24.6 percent of customer satisfaction, in turn, customer satisfaction predicts 14 percent of CEBs. Regarding model validity, the endogenous latent variables can be classified as substantial, moderate or weak based on the R2 values of 0.67, 0.33 or 0.19, respectively (Chin, Peterson and Brown 2008). Accordingly, customer satisfaction (0.249) and CEBs (0.291) can be mentioned both as moderate

The result of the data testing shows intable 5. It analyses that cognition of hotel service quality towards RRS (i.e positively loyalty intention, price fairness and revenue management) influences customer satisfaction and CEBs positively. The results support H1, H2, and H3. Accordingly, the service quality in this concept contributes to customer satisfaction and CEBs. In addition, the magnitude of relationships between all variables is quite strong to indicate that hotel RRS exerts a powerful effect on customer cognition. It implies that excellent service quality can prove to be significant in rousing high satisfaction levels in customer and increasing their CEBs. For instance, the relationships between hotel service quality, customer satisfaction, and CEBs indicate that customers who experience excellent service quality are more likely to satisfy and in turn to engage and remain positive attitudes with hotel RRS. It is therefore imperative to provide well-perceived service quality by ensuring hotels’ price fairness, building revenue management and loyalty intention to satisfy their customers and enhance customer engagement towards a suitable hotel RRS.

Note: t-values: 2.57 (p<0.01)

4.3. Mediating effect of customer satisfaction

The proposed concept determines hotel service quality as an exogenous construct while customer satisfaction and CEBs as endogenous constructs. It was estimated by constraining the direct effect of service quality on CEBs to examine the mediating effect of customer satisfaction. All four necessary conditions for the existence of mediation effect were met in the study (Baron and Kenny 1986). Three of the requirements including b12 (SQ→CS), b13(SQ→CEB) and b23(CS→CEB) were significant. Lastly, the condition is met if the parameter estimate between b13 (hotel service quality and CEBs) becomes insignificant (full mediation) or less significant (partial mediation) than the parameter estimate (bSQ to bCEBs) in the constrained model. The outcome acknowledges that customer satisfaction acts as a partial mediating role (b13= 0.437, t = 1.4862, and bSQ to bCEBs =. 0.525, t = 2.3311). Moreover, its indirect effect was examined to explore its role. The indirect effect of hotel web-site quality on CEBs through customer satisfaction was .000767, which came from b12*b23. The total effect hotel web-site quality on CEBs through customer satisfaction was 0.0230 which collected from b13+b12*b23 with p < .05. To conclude, customer satisfaction through the mediator of service quality towards hotel’ room rate strategy is effect by measurement items of price fairness, revenue management and loyalty intention.

CONCLUSION

With the changes in the nature of hotel and tourism in modern society, establishments can hardly depend on their present performance or work in the same competitive environment for their whole life business. To begin with, given the ever-increasing revenue, it is a sensible decision for hotels to opt for success. As an increasingly important policy, an effective hotel room rate strategy is offering unparalleled benefits to hotels. Little research has been carried out to assess the features and contents of room rate strategy from the perspective of service quality and how it affects customers’ satisfaction and engagement behaviors. The current study fills this research gap by conducting an empirical study and examining the interrelationships between hotel service quality, customer satisfaction and CEBs.

Findings from this study explicate a number of significant issues (such as challenges, developments and prospects of customers) to hotel service quality regarding customer perceptions of room rate strategy and its impacts on satisfaction levels and behaviors. Empirical findings of this study validate that service quality towards customer perception of hotel room rate strategy is a second-order complex construct with three primary dimensions including price fairness, revenue management and loyalty intention. These findings are in line with the studies conducted bySun, Law and Tse (2015) about customer behaviors when purchasing tourism-related products in ‘last-minute sales mode’ among different OTAs but lack of consideration on RRS like this study;Yang and Leung (2018) about cross channel prices andNair (2018) about pricing strategies impact revenue management performance but only focus on various factors behind price discounts and non-pricing strategy; orAlgeciras and Ballestero (2017) only mentioned the effect of revenue management on luxury hotels.

Hence, hotel revenue managers need to develop a better navigational structure of revenue management to ensure better hotel room rate strategy which may result in customers getting to their satisfaction and engagement behaviors. This finding is in line with the recent literature related to competitive advantages in the lodging business.

As consumers become more proactive and technologically savvy, they partake more in the diversity of hotel channels and have higher requirements for hotels’ parity presence. Therefore, to capture the higher levels of customer satisfaction and CEBs perceived service quality towards customer perception of hotel room rate strategy, hotel managers should allocate more resources to meet customer needs for price fairness, loyalty intention and revenue management. Overall findings of this study related to dimensions of hotel room rate strategy are important for hotel managers as they decide the allocation of resources to improve business performance by selling more rooms from various offerings for various niche markets. It implies that customers with perceived service quality towards the hotel room rate strategy will tend to have higher satisfaction and CEBs.

The future study needs to consider limitation for some reasons. The concept results play a role in full-service hotels (4 to 5-star standard) may not be similar in limited-service hotels (below 3-star hotels). There are a few more important conceptualizations related to hotel room rate strategy in the literature such as discounted policy, seasoning factors, events, customer’ time and budget concern, etc.