INTRODUCTION

Spiritual tourism is a journey to find the purpose of life and it is a life exploration that goes beyond the self. It contributes to the balance of the body-mind-spirit, which may or may not have a relationship with religion (Smith, Macleod and Robertson 2010). Hitherto many researchers have tended to use ‘spiritual tourism’ interchangeably with ‘religious tourism’ which creates confusion about the conceptual differences between the two ideas. In this article, it is argued that, while some researchers have provided insights into the “spirituality puzzle”, most have failed to provide a holistic picture (Wilson 2016). Through a review of articles related to religion and spirituality, conceptual constructs underpinning religion and spirituality are explored. In order to provide a platform for future scholars to investigate the phenomenon of spiritual tourism, the constructs are either taken from other disciplines or from within the tourism context.

Traditionally, religion and spirituality have been viewed from the perspective of something being sacred, divine and holy in thought and action. According toPargament (1997;1999), spirituality is a quest for the sacred, a process through which individuals try to explore, maintain, and transform whatever they hold sacred in their lives when needed. The same trend follows in the tourism industry, in which spiritual tourism is defined as a ‘physical journey in search of truth, in search of what is sacred or holy’ (Vukonić 1996, 80). Spiritual tourism is also related to different sacred places, such as the Vatican for Catholics, the Ganges, temples and ashrams in India for Hindus, Mecca and the Sufi shrines for Muslims (Timothy and Iverson 2006). Some other researchers separate spiritual tourism from the religious context. For instance,Norman (2012) viewed spiritual tourism as a phenomenon in leisure travel that constitutes a self-conscious mission of spiritual betterment. This is supported byWilson, McIntosh, and Zahra (2013), who defined spiritual tourism as an individual search for the purpose of life from and through travel. These definitions and understandings of spiritual tourism generally fail to clarify for researchers and readers whether religious tourism is similar to, or different from, spiritual tourism.

Given this, making a distinction between the two requires the development of a conceptual model of spiritual tourism which should be based on fundamental concepts of spirituality common to all religions. By reviewing different articles and adopting the Spiritual Intelligence Model (Hanefar, Sa’ari, and Siraj 2016), this article propounds a conceptual model for spiritual tourism that could inform future research on the subject. The model is intended to build a bridge between religion and spirituality in tourism and to provide researchers with a framework that goes beyond the boundary of any specific faith or belief.

1. LITERATURE REVIEW

1.1. Religion/ religiousness and spirituality

For the past three decades, scholars have made efforts to study, investigate, and institutionalise the terms ‘religion’ and ‘spirituality’ (Emmons and Paloutzian 2003;Giordan 2007;Moberg 1990;Oman 2013;Turner et al. 1995;Zinnbauer and Pargament 2005,Zinnbauer, Pargament and Scott 1999). The terms have been explored in different ways and from various perspectives, but no precise and robust distinction between them can be found in either modern or traditional sources. Frequently they are given as inter-related and complementary, such differentiation as is detectable coming from the contexts in which they are used. Nonetheless, spirituality has started to attain meanings that distinguish it from religion (Turner et al. 1995).

Religion is defined as a structured system of beliefs, practices, rituals, and symbols aimed at facilitating proximity to the sacred or transcendent (Koenig, McCullough and Larson 2000). Meanwhile,Wulff (1997) viewed religion/ religiousness as a supernatural power to which people are motivated or engaged, sensing the power, and performing rituals in respect of it. Definitions of religiousness range from institutionalised beliefs to a system of beliefs in a divine power to "the feelings, acts, and experiences of individual men in their solitude. They apprehend themselves to stand in relation to whatever they may consider as divine" James 1961, 42 inZinnbauer et al. 1997.

Spirituality, on the other hand, is defined as divine love experienced as an assertion that contributes to self-confidence and a feeling of worthiness, divine intercession or inspiration, heightening awareness that involves more than physical states, psychological feelings, and social roles (Van Kamm 1986). In addition,Van Kamm (1986) stated that spirituality is also considered to be a form of belief that there is something else entirely to life than what one can see or completely comprehend, a feeling of wholeness, inner harmony, and peace. A similar definition is given byHawks (1994), in which he defined spirituality as encountering oneness with nature and beauty, and a feeling of connectedness with self, others and a higher power, together with concern for, and commitment to, a possibility that is greater than oneself.

Peteet (1994) inZinnbauer and Pargament (2005) stated that religiousness is connected to one’s belief and related to a particular practice. Spirituality is more concerned with the meaning and purpose of life. Similarly,Stifoss-Hanssen (1999) limited sacredness to religion and associated spirituality with other dimensions, for example, the purpose of life, existence, and community.Pargament (1999) claimed that spirituality is positioned as a focal point of religion and its primary role consists in the quest for what is sacred.

The above definitions of religion/ religiousness and spirituality present different perspectives on belief, attitude, practice, environment, attributes, feelings, and behaviours. Nonetheless, definitions of religiousness and spirituality remain relatively inconsistent across researchers (Zinnbauer and Pargament 2005). Trying to find the sacred does not necessarily require spirituality, which is related to soul searching with spiritual values beyond the supernatural. The religious dimension, by contrast, is defined by the holiness or sacredness of the divinity. In brief, religiousness and spirituality overlap but are not identical; they are, however multidimensional and complex, and, as terms, develop and change over time. The arguments on religiousness and spirituality have undoubtedly affected the tourism industry.

1.2. Religious tourism vs spiritual tourism

Travel provides an opportunity for people to retreat from daily routines to seek variations in the form of leisure, recreational, religious or spiritual activities. However, in this fast-changing world, these overlap in many ways, and travel based on religion and spirituality has gained more attention across the world. Many researchers have discussed spiritual tourism in the light of religiousness (Almuhrzi and Alsawafi 2017;Norman 2011;Power 2015;Rocha 2017;Sharpley and Sundaram 2005;Tilson 2005) with the majority relating to Christianity, Islam, and Hinduism. Meanwhile, some researchers believe these constructs as related but not identical and spirituality could go beyond the context of religion (Kujawa 2017;Norman and Pokorny 2017;Singleton 2017;Wilson, McIntosh and Zahra 2013).

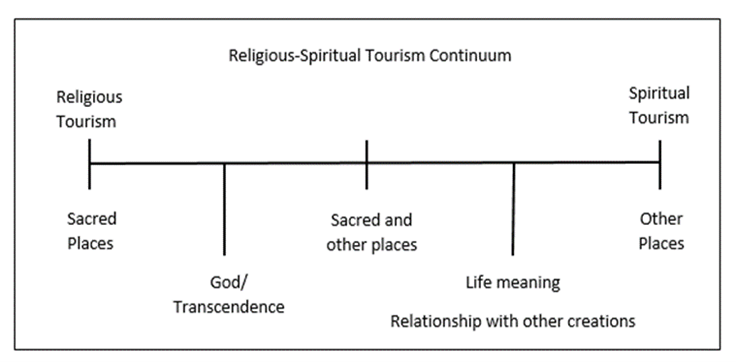

Religion has presumed a vital role in the advancement of leisure and tourism over the centuries and has affected how individuals use their leisure time (Kelly 1982 cited inOlsen and Timothy 2006). As indicated by the World Tourism Organization (UNWTO), approximately six hundred million national and international religious and spiritual voyages occur annually, of which 40% are located in Europe and over half in Asia (2011). Religion and spirituality are the critical motivators for many to visit sacred places, but this is not a universal rule, since those visiting sacred places do not necessarily belong to the associated faith. According toEbadi (2014), a place is visited for different reasons, such as religion, culture, nostalgia or even adventure. To be in a spiritual state while travelling or being a tourist, one should not only limit the visit to sacred places; it could be extended to take in other places, which can positively affect lives and relationships in a similar way. The journey between religious tourism and spiritual tourism leads to a continuum of religious – spiritual tourism, as illustrated inFigure 1. There could be overlaps, for instance, a person visiting a religious site is able to find the meaning of life and increase his/ her spirituality. While for other persons who visit ‘other places’, they could gain God-consciousness and self-transcendence.

The aboveFigure 1 is further supported by literature defining religious tourism and spiritual tourism.

Heidari et al. (2017) defined religious tourism as a visit/pilgrimage to sacred places and to participate in religious ceremonies that will fulfil religious duties. A similar definition is given byRinschede (1992) andSmith, Macleod, and Robertson (2010), who defined religious tourism as visits to a sacred or religious sites, monuments or other destinations from religious motives related to a specific faith. From a contemporary standpoint, religious tourism may be related to individual spirituality that is, a tourist may not be religious but will visit holy or sacred places for personal meaningfulness.Shinde (2007) stated that a contemporary religious journey or visit could be based on the visitor’s own beliefs to fulfil religious needs and also for other recreational needs.

In view of spiritual tourism,Haq and Medhekar (2019) have coined the term as an act of travelling domestically or overseas to visit spiritual places such as mosques, churches, and temples. They also include natural environments such as forests, oceans, lakes, spiritual gardens, wildlife parks, botanical gardens, caves, and rocks as means to fulfil the need for being grateful to the Almighty, to gain forgiveness and inner peace. Some opposing views, however, have focused on spiritual tourism as an individual phenomenon aimed at exploring life beyond oneself to balance the body-mind-soul, to gain self-consciousness for spiritual betterment and to fulfil one’s purpose in life (Norman 2012;Smith, Macleod, and Robertson 2010;Wilson, McIntosh, and Zahra 2013).

Religious tourism is related closely to the tourist experience and places with sacred elements and specific faith whereas spiritual tourism goes beyond the context of religion including the natural environment, relationships between mind, body and soul, and personal meaning. Nonetheless, the elements of spirituality are embedded in religion, and the elements of religion could be seen in spirituality. In this study, the term spiritual tourism includes the dimensions of religiousness and spirituality.

1.3. Dimensions of spiritual tourism

Spiritual tourism can provide a moment of calm reflection and it is a soul-searching process, a journey of experience. It has become a means to harmonise and reach a balance between mind, body, and soul (Smith, Macleod, and Robertson 2010). Many factors can lead an individual to embark on a spiritual journey and the spiritual connection or experience could happen before, during, and after the journey or visit. Furthermore, people from different cultures will have different versions, motives, and beliefs for spiritual tourism. The spiritual dimensions of contemporary tourism studies vary significantly among scholars and researchers. This section will look into the dimensions of spirituality in tourism, for instance, wellness, healing, personal development, motivation, restorative environments, spiritual transformation, self-awareness, and many others.

Cheer, Belhassen, and Kujawa (2017) proposed a conceptual framework for spiritual tourism that outlined two main drivers: the religious and the secular. According to these authors, secular drivers focus on the self-foregrounding motives such as wellness, adventure, and recreation to gain some kind of spiritual benefit, perhaps a stronger connection with the inner self or the achievement of a better form of consciousness. Religious drivers, on the other hand, emphasise motives that are underlined by religious adherence, ritualised practice, reiteration of identity, and cultural routine. Both secular (internal self) and religious drivers (external/ institutional) contribute to the understanding of the different dimensions of spiritual tourism.

Similarly, in a study done byCutler and Carmichael (2010), the dimensions of spiritual tourism are viewed from two perspectives: the influential and the personal. These are based on the tourist experience before, during, and after a particular journey or tour. The influence realm includes external factors, such as physical aspects, social aspects, and products/ services. Meanwhile, knowledge, memory, perception, emotion, and self-identity are among the internal factors under the personal realm. Both the external and internal factors experienced by travellers lead to motivation (either motivated or demotivated) and satisfaction (either satisfied or dissatisfied).

Meanwhile,Heintzman (2002) has developed a conceptual framework that suggests leisure experience provides an avenue for spiritual development. It allows individuals to work through spiritual difficulties and gain spiritual sensitivity. The developed framework allows travellers to recognise their inner-self and external surroundings, clearly indicating a strong relationship between leisure (external) and spiritual well-being (internal). Heintzman further stated that different individuals will experience different spiritual well-being when influenced by the dimensions of leisure style (activity, motivation, setting, time). In addition, one’s spiritual well-being could change according to the type of leisure activity. Similarly,Mannell (2007) argued that leisure activities positively influence one’s physical, psychological, and spiritual health. Heintzman’s framework also shows the effect of different leisure experience on different characteristics of spiritual well-being. This finding is in accordance with the study done byVukonić (1996, 18), in which it is stated that, ‘tourism provides people with the conditions for a constant search for spiritual enrichment and self-development’.

Heintzman (2013),Morgan (2010),Ponder and Holladay (2013), and other researchers have argued that there is a significant connection between tourism and spiritual development in the context of motivation, inner psychological development, self-development, and well-being.Heintzman (2013) andPonder and Holladay (2013) for instance, discovered that involvement in tourism activities offers positive spiritual outcomes and meaning such as transcendence benefits (connection to a higher power), spiritual transformation (betterment of self), eudemonic state (i.e. happiness), and many others. These findings are supported byCoghlan (2015), who explored how tourist experiences create positive emotions, engagement and meaning, thus enhancing participants’ well-being. All these studies clearly indicate that tourism has long been recognised for its potential restorative, hedonic or broader well-being outcomes, and significantly contributes to the enhancement of individual spirituality or inner psychological development (Morgan, 2010).

Dimensions such as transcendence, meaning, connection, awareness, socialisation, and altruism are also measured as part of the spiritual determinants of leisure travel and other tourist activities (Jarrat and Sharpley 2017;Little and Schmidt 2006;Robledo 2015;Smith and Diekmann 2017). A study byLittle and Schmidt (2006) identifies four important spiritual tourism dimensions; self-awareness, other-awareness, sense of connection, and intense sensation. The authors’ analysis revealed that travellers/ tourists gained an enhanced awareness of self, God or 'other', and felt a greater sense of connection with something beyond the self. In addition, they stated that travellers/ tourists experienced their spiritual leisure travel intensely and recognised a range of sensations including wonder, awe, fear, and release. This study proved that spiritual experiences emerge from leisure travels despite being neither collectively expected nor sought. AsWalsh (1999, 6) wrote, there is a ‘sense of meaning, inner wholeness, harmony and connection with others, a unity with all nature and the universe’.

In a similar vein,Jarrat and Sharpley (2017), identified touristic experience (particularly in a seaside experience) as a potential provider of emotional and spiritual significance. A number of clear themes emerge from the research that point to a spiritual dimension to the seaside experience, including a sense of connection, awesomeness, timelessness, and nothingness. Jarrat and Sharpley’s findings are supported byFisher, Francis, and Johnson (2000), who argued that a feeling of connection or reconnection to the environment, in general, can be considered spiritual. They identify four domains within which harmonious relationships are necessary for the achievement of spiritual well-being: are (1) the personal, (2) the communal, (3) the environmental, and (4) the transcendental. This shows that spiritual fulfilment can be achieved via connectedness of oneself to an immanent or transcendental power through the natural environment.Steiner and Reisinger (2006) carried out similar research in which they found that, through tourist activities, an intimate relationship between earth, sky, mortals, and divinity (wholeness and authenticity) is achieved. The ability to connect with other things and beings eventually enables one to achieve transcendental aims.

Robledo (2015) explored a dimension of tourism in which the outer search is the vehicle for an inner journey of spiritual development. He coined the concept of ‘tourism for spiritual growth’ through esoteric motivation. According to him, an individual undertakes an intentional “voyage of discovery” for inner awareness and transformation. The term is conceptualised as central dimensions of meaning, transcendence and connectedness. These dimensions were analysed in relation to the motivations it involves.Smith and Diekmann (2017) explored the relationship between diverse terminologies and perspectives as well as the ways in which various types of well-being can be derived through tourism experiences. They identified three main dimensions; pleasure, altruism, and meaningful experience.

The above discussion evinces more than forty dimensions of spiritual tourism. They can be categorised into two main parts; the internal and external dimensions. Some researchers have connected these two elements in order to demonstrate spiritual attainments through travel or taking a journey, while others focus solely on the element of religiosity or the sacred with the outcome of spiritual enlightenment. There are a few others who are more secular, viewing the dimensions of spiritual tourism without the element of religiosity.

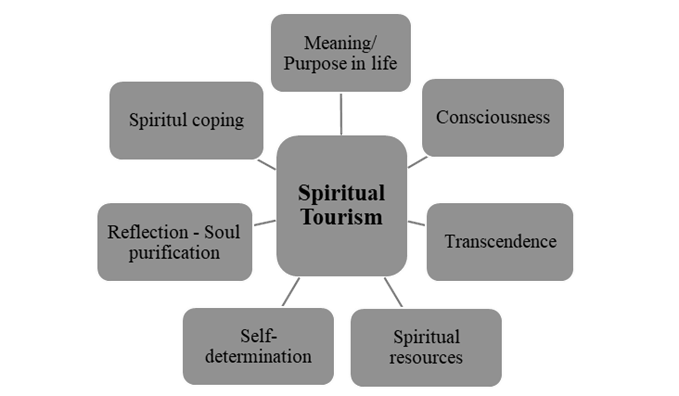

To organise and discuss these dimensions of spiritual tourism, we have adopted the spiritual intelligence themes identified byHanefar, Sa’ari and Siraj (2016). In their article titled “A Synthesis of Spiritual Intelligence Themes from Islamic and Western Philosophical Perspectives”, they identified seven spiritual intelligence themes through thematic analysis; meaning/purpose of life, consciousness, transcendence, spiritual resources, self-determination, reflection-soul purification and spiritual coping (with obstacles). This model was developed based on the fundamental concept of spirituality from both Islamic and Western perspectives which is adaptable beyond the boundary of religion. The assimilation of different dimensions of spiritual tourism and the Spiritual Intelligence Model results in a systematically organised conceptual model for spiritual tourism.

2. RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

Electing an appropriate methodology will ensure validity and reliability in research (Frankel and Wallen 1996). The purpose of this study is to build a conceptual model for spiritual tourism drawing from the literature on spirituality, religion/ religiousness, and tourism. In order to build a reliable and valid study, two main steps were involved; literature search and qualitative research.

2.1. Literature Search

In this stage, to develop a Conceptual Model for Spiritual Tourism, the researchers adapted similar procedures to those involved in the ‘Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses’ (PRISMA) Framework, which consists of four main steps; identification, screening, eligibility, and included. Using online search engines - Google Scholar and Nottingham University Search, thousands of articles containing the term ‘spiritual religious tourism’ were identified. Most of these articles use the term spirituality and religiosity interchangeably. As for the purpose of this study, the main sources consisted of both elements of religiousness as an extrinsic motivation focus on institution and spirituality as an intrinsic motive focus on self. In this search, hundreds of relevant articles were found. Additionally, a simple random sampling was done, in which every 10th article was chosen. For the articles to be eligible and included in the study, articles were chosen that comprise at least three out of seven themes from Spiritual Intelligence Model ofHanefar, Sa’ari and Siraj (2016); meaning/ purpose of life, consciousness, transcendence, determination, spiritual resources, spiritual coping with obstacles, and reflection - soul purification. Twelve articles are included as our final sample.

The seven themes of the Spiritual Intelligence Model were validated byHanefar (2015) andHanefar, Sa’ari, and Siraj (2016) through experts’ views from different backgrounds; an academician, a philosopher, a researcher, and a scholar. For the purpose of this study, to validate the model in the context of tourism, the authors gained the views of two experts on spirituality and tourism; one from Malaysia and the other from Turkey.

2.2. Qualitative research

The 12 articles that were selected using the PRISMA framework were analysed using content analysis, which is a qualitative research method. According toCreswell (1994), qualitative research is the best choice when a researcher intends to understand social or human problems, based on building a complex, holistic picture, formed with words, and conducted in a natural setting. This is supported byChua (2014), who states that human behaviour, emotions, characteristics, and difficult situations could only be understood qualitatively. So, in this study, a qualitative research method is adopted to explore the descriptive and complex nature of spiritual tourism.

The content analysis was done to gain an in-depth understanding of the phenomenon being studied. The main purpose in conducting a content analysis was to discover the dimensions of spiritual tourism. There were a few steps involved (Ary, Razavieh and Sorensen 2009):

1. Specifying the phenomenon to be investigated. In this study, the investigated research phenomenon is spiritual tourism dimensions.

2. Selecting the articles from which the analyses are to be made. This study involved twelve main articles.

3. Formulating comprehensive and mutually exclusive codes based on the chosen articles. More than forty codes (and sub-codes) are identified as perTable 1:

4. Deciding on a sampling plan. (Not applicable at this stage as a simple random sampling strategy was used during the literature search to find suitable articles).

5. Training the coders. (Not applicable as the researcher had the sole responsibility in the coding activity).

6. Analysing the data. Data were analysed using secondary sources such as journal articles, books, and past studies to support the selected themes.

The established codes are mapped against the themes of the Spiritual Intelligence Model (Hanefar, Sa’ari and Siraj 2016). These themes are the foundation for the establishment of themes for a spiritual tourism model. The seven themes are given inTable 2:

| Theme 1 | Meaning/Purpose in life |

| Theme 2 | Consciousness |

| Theme 3 | Transcendence |

| Theme 4 | Spiritual resources |

| Theme 5 | Self-determination |

| Theme 6 | Reflection – Soul purification |

| Theme 7 | Spiritual coping (with obstacles) |

As perTable 1, more than forty codes (dimensions of spiritual tourism) were recognised. Some of the codes are overlapping. These codes were compared and contrasted. Some codes are categorised under the same theme and a particular code is categorised for different themes (Table 3). The detailed mapping is given inAppendix 1.

|

Meaning/ purpose of life | Consciousness | Transcendence | Spiritual resources | Self-determination | Reflection-Soul purification |

Spiritual coping (with obstacles) | |

| Cheera, Belhassen and Kujawa (2017) | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Coghlan (2015) | X | X | X | ||||

| Cutler and Carmichael (2010) | X | X | X | X | |||

| Heintzman (2002) | X | X | X | ||||

| Heintzman (2013) | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Jarrat and Sharpley (2017) | X | X | X | ||||

| Little and Schmidt (2006) | X | X | X | X | |||

| Morgan (2010) | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Ponder and Holladay (2013) | X | X | X | ||||

| Robledo (2015) | X | X | X |

| |||

| Smith and Diekmann (2017) | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Steiner and Reisinger (2006) | X | X | X |

3. FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION: A CONCEPTUAL MODEL FOR SPIRITUAL TOURISM

Based onTable 3, the dimensions of spiritual tourism from twelve different sources were mapped accordingly with the seven themes of the Spiritual Intelligence Model. This categorisation has given a clearer view in having more solid and concrete themes to present the spiritual tourism dimensions. All the seven themes are discussed towards developing the Conceptual Model of Spiritual Tourism:

3.1. Meaning/ purpose of life

One’s life fulfilment could be achieved while travelling. A journey in search of one’s life path and life identity could create a tsunami in the tourism industry, termed spiritual tourism. According toBrämer (2009), spirituality is a search for the achievement of life balance, bringing mind, body, and soul together via physical movement (and mobility) in nature. Similarly, Graburn (1989) cited inSharpley and Jespen (2011) stated tourism is functionally and symbolically equivalent to other institutions that humans use to embellish and add meaning to their lives. This indirectly indicates that spiritual tourism contributes to one’s search for meaning in life. Wellness tourism, for instance, is categorised under spiritual tourism (Steiner and Reisinger 2006): during a journey, tourists who are aiming at realising better well-being create a meaningful life and clear purpose. Likewise, according to the National Wellness Institute (2000), spirituality involves seeking meaning and purpose in human existence. It includes the development of an appreciation for the depth and expanse of life and the natural forces that exist in the universe. The development of spirituality in one’s life will enable the individual to observe the scenery along the path and the world around with appreciation and wonderment in finding meaning/ purpose in life.

Activities, including tourism, can affect one’s spirituality, if these activities provide profound meaning and purpose of life. In a phenomenological study done byWilson, McIntosh and Zahra (2013), it was found that tourism experience allows tourists to engross in the form of experience initiated on their quest for meaning and the purpose of life derived primarily through religious and other activities. As seen inTable 3, all the authors relate the dimensions of spiritual tourism to meaning/ life purpose. There is no doubt that religion or non-religion travel experience, both, almost all the time are related to meaning/ purpose of life. Fundamentally, any activity involving spirituality will comprise one’s quest for meaning that inevitably will be undertaken by every human being (Miner-Williams 2006;Tanyi 2002).

3.2. Consciousness

Heintzman (2002) proposed a model of leisure and spiritual well-being in which he stated that leisure experiences will lead consciously or unconsciously to sensitisation of one’s spirituality and spiritual development. Similarly, visiting a place - either religious or non-religious - could trigger one’s inner self (Morgan 2010) to contemplate his/ her creation in this world and the intimate relationship (Steiner and Reisinger 2006) to the Creator and other creations in the natural world. This statement is strongly supported byLittle and Schmidt (2006), who discovered travellers/ tourists are able to reach a heightened state of self-awareness, God-awareness or other-awareness. They sensed a higher wisdom in their connection with something beyond their self, and experienced their spiritual leisure travel deeply, recognising different kinds of feelings.

Some researchers (Cheera, Belhassen and Kujawa 2017;Coghlan 2015;Jarrat and Sharpley 2017;Robledo 2015;Smith and Diekmann 2017) have argued that spiritual experience, engagement, healing, feeling of connectedness, altruism, and meaningful experience are achieved during travel or tourist activities. All these elements contribute to heightened consciousness and spiritual development. This consciousness is the substance of a person's association on the planet that includes the emotion, the mind, and the complete self of the person (Relph 1990 and Smith 1982 cited inLi 2000).

3.3. Transcendence

One essential elements of spirituality is transcendence.Amram and Dryer (2008) defined transcendence as moving beyond the distinct individualist self into a unified wholeness.King and DeCicco (2009) give a similar meaning to Amram and Dryer, in that they demarcated transcendence as a capacity, which occurs outside the ordinary consciousness, like, for example, sacredness, inter-connectedness, and non-materialism.

Relating spirituality to tourism, directly or indirectly, transcendence is considered to be one of the main elements to experience while travelling or during tourist activities (Cheera, Belhassen and Kujawa 2017;Heintzman 2002;Heintzman 2013;Little and Schmidt 2006;Morgan 2010;Robledo 2015;Steiner and Reisinger 2006). For instance, in a study conducted byHeintzman (2013) among 509 wellness tourists, he discovered that transcendence is one of the main factors as to why tourists engaged in wellness tourism and it is among the most highly valued factors. Similarly, inWilson, McIntosh, and Zahra (2013), transcendence experience was revealed during travel when the journey provided a moment of inspiration and heightened energy. Such inspiration shows that the transcendental experience is not only achieved in a religious context, but also beyond religion and the experience - it significantly contributes to create wholeness in oneself.

3.4. Spiritual resources

For an individual to cope with daily life and various spiritual activities, he/she needs resources. Spiritual resources are not only used to solve problems (Emmons 2000) but, as a whole, to guide individuals to achieve success and human excellence in life (Hanefar 2015). For instance, according toHeintzman (2008), upper supremacy, spiritual practices, and faith community can be categorised as spiritual resources. Spiritual resources can also be in any form of inputs that are used to the pursuit and reach sacredness, moral, and ethical values in life, like, in the form of people, materials, places, experience, environment, and surroundings (Hanefar 2015;Hanefar, Sa’ari, and Siraj 2016).

In tourism, spiritual resources contribute significantly to spiritual development through spiritual experience (Ambrož and Ovsenik 2011), inner psychological development (Morgan 2010), and a restorative environment (Heintzman 2013). In addition, the element of spiritual resources in wellness and healing, socialisation, journeying, recreation and leisure, religious observance, ritualised practiced, identity, cultural practice (Cheera, Belhassen and Kujawa 2017), and meaningful experience (Smith and Diekmann 2017) also act as contributing factors for spiritual enhancement. According toMorgan (2010), spiritual resources such as tourist activities and places enable one to achieve experiential learning opportunities that are directly concentrated on experiencing the otherness of nature and different cultures. In addition, these spiritual resources allow communication with other travellers and the host community through joint learning and discourse, and offers opportunities for reflection and contemplation. In total, all these factors enable travellers/ tourists to develop their spirituality.

3.5. Self-determination

Individuals or tourists engage in travel activities and experiences when they are motivated (Heitmann 2011), and an important elements of motivation is self-determination. Self-determination is a vital force for spiritual development or psychological well-being (Hanefar 2015). In the context of tourism, the Self-determination Theory (SDT) ofDeci and Ryan (1985) links to personality, human motivation, and optimal functioning. It suggests that there are two main forms of motivation; intrinsic and extrinsic, and both are prevailing forces in shaping oneself (Deci and Ryan 2008). From the perspective of spiritual tourism, it could be said that self-determination is a form of intrinsic motivation experienced before, during, and after the travel activity or experience. It is an internal drive that inspires tourists/ travellers to be self-aware (Little and Schmidt, 2006) and behave in certain ways. Evidently, internal drive enhances one’s spiritual and personal transformation and development (Cheer, Belhassen, and Kujawa, 2017;Heintzman 2013;Morgan 2010;Ponder and Holladay 2013).

Furthermore, tourist/ travel experience involves the individual pursuit of identity, self-realisation, and the development of one’s inner psychology (Morgan 2010;Selstad 2007). Tourist experience could happen at the destinations, before the journey or after the completion. Hence, it needs to be accompanied by high self-determination. Without high self-determination, individuals will fail to internalise their tourist experience, especially in the context of spirituality. Cutler and Carmichael stressed that (2010), motivation and satisfaction are two crucial elements of spiritual tourism. Tourists/ travellers with high self-determination are able to achieve self-actualisation that is the highest form of motivation - Abraham Maslow 5-Need Theory (Block 2011) and are able to satisfy themselves. Thus, the tourist experience will be meaningful (Smith and Diekmann 2017) and valuable. A tourist/ traveller with high self-determination is able to motivate oneself and achieve healthy psychological development and become a better person spiritually.

3.6. Reflection - soul purification

It is a common belief that, through involvement with religious activities, one is able to reflect upon oneself and purify the soul. In contrast, many researchers have proved that reflection - soul purification could take place indirectly through non-religious activities, such as those associated with tourism (Cheera, Belhassen, and Kujawa 2017;Coghlan 2015;Cutler and Carmichael 2010;Heintzman 2013;Little and Schmidt 2006;Morgan 2010;Ponde and Holladay 2013;Smith and Diekmann 2017). These authors relate elements such as self-awareness, motivation, satisfaction, inner psychological development, spiritual experience, restorative environment, spiritual well-being, eudemonic experience, positive human transformation, altruism, and meaningful experience as major dimensions in spiritual tourism. These dimensions enhance the ability for self-reflection and at the highest level, purify the soul.

The existence of reflection-soul purification elements in spiritual tourism can be seen in many tourist activities or experiences, such as meditation, yoga, wellness and healing, pilgrimage, and others (Bowers and Cheer 2017;Kelly 2012;Ponder and Holladay 2013;Smith and Kelly 2006). For instance, when a tourist visits a wellness centre (a restorative environment), he or she, through meditation, is able to achieve self-awareness, calmness, and high consciousness. The process builds motivation, satisfaction, and the existence of altruistic character – all of which contribute to positive human transformation. Similarly,Reisinger (2013) stated that alternative tourism such as religious/ spiritual tourism is able to deliver significant educational value and enhances a motivation for exploration, self-realisation/ self-reflection, and self-improvement. As a whole, it will give meaningful spiritual experience to the tourist/ traveller.

3.7. Spiritual coping (with obstacles)

Several studies have identified the importance of spirituality in the leisure coping process (Gosselink and Myllykangas 2007;Heintzman 2008). The element of spirituality has been found to bear on coping with obstacles during and after leisure/ travel time. It appears that factors related to reflection-soul purification also reflect on spiritual coping ability, these being, wellness and healing, restorative environments, spiritual transformation, spiritual well-being, inner psychological development and growth, and meaningful experience (Cheera, Belhassen, and Kujawa 2017;Heintzman 2013;Morgan 2010;Smith and Diekmann 2017). These researchers support the view that spiritual coping is present during and after leisure/ travel time.Heintzman’s (2002) study further strengthens the leisure coping ability claim. According to Heintzman, leisure/ travel experiences deliberately or otherwise offer prospects for "grounding" or "working through" difficulties that enhance one’s spirituality.

In a study done byHeintzman and Mannell (2003), structural equation modelling, AMOS was employed to examine the direct and indirect relationships among the components of leisure style, spiritual functions of leisure, and spiritual well-being. The model suggests that some components of people’s leisure lead to certain behaviours and experiences that sustain or enrich their spiritual well-being. The spiritual functions of leisure might as well function as coping strategies to mend the negative influence of time pressure on spiritual well-being. This clearly gives some evidence for how the dimension of spiritual coping with obstacles could be achieved during leisure/ travel. Admittedly, not many studies are available to support this claim, but that does open an avenue for future research.

The outcome ofTable 3 and the above critical discussion have resulted in the formation of a Conceptual Model of Spiritual Tourism (Figure 2). This model consists of seven highly inter-related themes or constructs that influence spiritual tourism. It provides a systematic pathway for us and other researchers to conduct studies on spiritual tourism in future.

The built conceptual model of spiritual tourism indicates that tourists/travellers are able to purify themselves through many tourist activities such as yoga, meditation, reflection, and others. They are able to reflect upon themselves and realise the meaning- purpose of life. With a purpose in mind, they are motivated to have high self-determination, gained through spiritual resources such as tourist places, nature, interaction with human beings, and others. By increasing knowledge and wisdom through different spiritual resources, tourists will transcend themselves to be the best they can to reach the highest potential of their real self, thus allowing them to gain higher transcendental awareness that leading to high consciousness. High state of consciousness will create a high ability amongst tourists/ travellers to cope with obstacles/ problems in which finally lead them to achieve a great satisfaction and outcome from their travel/ tourist experiences. These descriptions are one possibility as how all the dimensions could be inter-related. This model could be used as a whole or being used individually to reflect the essence of spiritual tourism.

CONCLUSIONS

For this study, the researchers reviewed many secondary sources, concentrating on twelve journal articles chosen via an adaptation of the PRISMA Framework. A content analysis was done of this sample to discover the dimensions of spiritual tourism. More than forty codes were identified and these codes were mapped against the Spiritual Intelligence Model (Hanefar, Sa’ari, and Siraj 2016). This particular model was adopted as it is a generic model and has been established as fundamental to spirituality, being viewed holistically beyond the boundary of religion. The outcome of the study is the formation of the Conceptual Model of Spiritual Tourism. This will provide a basic and systematic indicator for research related to tourism and spirituality. All the seven dimensions - meaning/ purpose of life, consciousness, transcendence, spiritual resources, self-determination, reflection – soul purification, and spiritual coping (with obstacles) could be used collectively or individually, both, in the context of traditional and contemporary views of spiritual tourism study. Some of the dimensions or themes from this model, for instance, meaning, reflection, and spiritual resources could create a niche market to positively contribute to the sustainable development of the spiritual tourism industry. This will impact planning for travel operators and organisations, giving them scope to access a new tourism segment that could increase the overall number of tourists. Furthermore, this development will lead to better employment opportunities, provide quality experiences to tourists/ travellers, respect local communities, preserve the natural environment, and bring many other benefits. When a destination is commercialised with the correct and perfect method, it will help to create and encourage the stimulation of economic development. The main limitation of the study is that only twelve main sources were used to form the major coding categories. In the future more sources could be added that deal with more diversified spiritual tourism dimensions. Besides, some of the built dimensions might not be suitable to certain contexts. Nonetheless, it is our hope that this study could contribute greatly to the field of tourism and spirituality, and bring positive outcomes to all the stakeholders involved either directly or indirectly.