INTRODUCTION

Human beings have always shared goods and services, which has benefited social and cultural relations. However, from the twentieth century on, the aggravated consumption in the capitalist system led to the exploitation of natural resources, creating concern about the rational and adequate use of such resources and developing sustainable business models (Botsman and Rogers 2011). The travel industry as a whole is affected by these new models and platforms (Guttentag 2015;Zhu et al. 2017).

Airbnb stands out as one of the leading companies in the sharing economy, operating an online marketplace that connects people who own a place with travelers looking for lodging and accommodation (Zervas et al. 2017). In Brazil, in 2018, the direct economic impact generated by Airbnb totaled BRL 7.7 billion, up 92% from 2017 (InvesteSP 2019).

In the online environment, trust between strangers is established primarily through reputation, which is responsible for determining the level of trustworthiness based on the participant’s online behavior (Schor 2014). Indeed, as users are urged to express their opinions about the service used, reviews and ratings have become essential for Airbnb and similar platforms, as they help establish trust between guests and hosts. Individuals with a high reputation are generally considered more trustworthy than those with a low reputation (Qiu et al. 2018).

The rise of Airbnb has mainly affected the hotel sector, real estate markets, and the need for regulatory frameworks (Guttentag 2015;Hassanli et al. 2019) and has transformed thousands of individuals into hospitality micro-entrepreneurs making tourist tourists accommodation a political issue in several countries (Guttentag and Smith 2017), making it of worldwide and academic interest. Scholars and professionals have valued this form of user-generated information. It points out new trends, impacts the reputation of companies and destinations, and reveals consumer behavior regarding decision-making and their level of satisfaction with the products and services offered to them.

Several studies investigate the attributes that influence the tourist by analyzing online reviews and have produced a range of similar but sometimes contradictory evidence. There are controversies regarding the importance of each aspect in the studied destination and the order of precedence of each Airbnb experience dimension also varies across different studies (Cheng and Jin 2019). Thus, users' diverse backgrounds, such as cultural differences or surrounding environments, should be considered when researching a global phenomenon like Airbnb.

Airbnb research publications started in 2015 (Andreu et al. 2020) most have been published recently (Humes and Freire 2020) and were conducted primarily by researchers in the US, Canada, and Europe (Guttentag et al. (2018)). Regarding the geography of the study sites,Guttentag et al. (2018) showed that most studies (40.2%) collected their data in the US/Canada, 29.5% in Europe, and only 1.8% in the Caribbean/Latin America.

In Brazil, there are still research gaps on the subject, and Fortaleza, capital of the state of Ceará, a state in northeastern Brazil, is a tourist destination predominantly of sun and sea, with growing tourist demand, receiving in 2018 a little more than three and a half million tourists (Secretariat of Tourism 2019) and where the Airbnb usage has been growing along with the number of offers (locations available for hosting) (Pinheiro 2017).

In this context, it is interesting to know the user experience in northeastern Brazilian tourist destinations and understand what affects the user experience in this type of destination. Thus, this research addresses the following problem: What is users’ experience using Airbnb hosting services in Fortaleza, Ceará, Brazil?

In this way, this study aims to identify the critical attributes of the experiences of Airbnb users visiting the city of Fortaleza through the reviews published on the platform, in the context of the growth of the sharing economy worldwide and the changes occurring in the tourism lodging market. To this end, it identifies the most relevant aspects of the user experience expressed in the reviews and the polarity of feelings associated with the themes addressed herein.

The attributes identified in this study can refine your rating items and develop good practices and guidelines to assist Airbnb and hosting hosts with service improvements. It contributes by understanding Airbnb user experiences in a Brazilian tourist destination.

1. THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

1.1 Airbnb

Airbnb is an online marketplace that enables ordinary people to rent out their homes or vacant rooms and spaces through a platform to market unique stays and experiences, connecting hosts and guests online or through mobile devices to book spaces and experiences around the world.Guttentag et al. (2018) defines it as a platform on which individuals can rent their spaces as tourist accommodation, involving an entire place (house, condominium) or a private room in a residence where the host is present.

Since its foundation, Airbnb has grown from a single air mattress on the founders' apartment floor to 5.6 million private accommodation offerings and four million hosts (55% women) in more than 220 regions and countries worldwide (Airbnb 2020), and it has accommodated over 825 million visitors through its online marketplace.

In 2019, 54 million active bookers worldwide booked 327 million nights and experiences on the platform (Airbnb 2020). Moreover, about 69% of the company’s yearly revenue was generated from repeat guests, which seems to vouch for the guests’ overall satisfaction with the platform (Airbnb 2020).

The motivation behind Airbnb’s success is a combination of factors, among which price stands out, along with the diversity of accommodations, dissatisfaction with the mass commoditization of large hotel chains, and the choice of staying in neighborhoods away from the typical hotel circuit, which, in turn, allows travelers to experience destinations in ways they were not used to in the past when tourists tended to stay near commercial and tourist centers, according to Airbnb, it is about “living like a local” (Gallagher 2018).

Airbnb encourages guests and hosts to publicly review each other, which is an essential factor since online reputation systems are highly likely to build trust between participants in online markets (Zervas et al. 2015). In 2019, over 68% of guests left reviews about their stays on the platform, added together, hosts and guests had posted more than 430 million reviews until September 2020 (Airbnb 2020).

1.2 User experience

Research on Airbnb confirms the importance of the company's ability to provide authentic and memorable experiences.Paulauskaite et al. (2017) andGuttentag and Smith (2017) highlight that Airbnb guests are primarily motivated by practical considerations (such as cost and location), but guests’ desire for authentic and innovative experiences is also essential.

In user motivation and (re)purchase intention,So et al. (2018) identify price, pleasure, and home benefits significantly explain the general attitude towards Airbnb.Liang et al. (2018) explored the relationships between satisfaction, trust and purchase intention in the context of Airbnb, proposed a theoretical framework distinguishing trust based on the Airbnb institution and trust in hosts, and concluded that trust is crucial to being the mediator between satisfaction and repurchase intention.

When analyzing the comments on the platform,Cheng and Jin (2019) identified that they were overwhelmingly positive and focused on the location, amenities, availability, flexibility, and communication of the hosts.Chang and Wang (2018) found that generations Y and Z were comparatively more focused on cost when making decisions about their stays, whereas generation X favored cleanliness; however, all ages were influenced by reviews and ratings.Tussyadiah and Zach (2017) found that they focused on the following factors: service, facilities, location, and neighborhood features, feeling at home, and the comfort of staying in a home.

In turn,Li et al. (2019) found that the Airbnb customer experience encompassed four dimensions (home benefits, personalized services, authenticity and social interaction) and showed how these dimensions significantly impact customers’ behavioral intentions.Zhu et al. (2021) identified that hosts, location, and amenities are the dominant aspects of the Airbnb experience and show that guest sentiment ratings towards hosts and amenities significantly impact guest recommendations, while location only influences guest recommendations in private rooms. AlreadyVon Hoffen et al. (2018) concluded that Airbnb guests attribute particular importance to cleanliness, comfortable beds, well-equipped kitchens, space, a good view, a quiet central location, and non-intrusive hosts.

Through the prism of co-creation of value,Camilleri and Neuhofer (2017) highlighted the experiential value of Airbnb,b focusing on six themes: arriving/being welcome, expressing feelings, evaluating accommodation and location, interacting and receiving help from hosts, recommending accommodation to other,s and thanking each other. Similarly,Johnson and Neuhofer (2017) point out that value emerged from a combination of the home, the surrounding community, and the hosts, while guests also found value in traveling like a local, cookin,g and cleaning with the host cultural learning, and relax.

Departing from the analysis of evaluations, the research byLyu et al. (2019) explores the principal dimensions and attributes of customer experiences. It presents seven dimensions: physical utility, sensory experience, core service, guest-host relationship, sense of security, social interaction, and local touch. In the research byWang and Jeong (2018) on satisfaction with the stay, the results indicate that the stay is affected by amenities and the host-guest relationship.

Controversies exist regarding the importance of each attribute. Previous studies considered the host-guest interaction as a main dimension (Chung 2017;Alrawadieh and Alrawadieh 2018;Yang et al. 2019) andLin et al. (2019) say that the significant and authentic social contacts between the hosts and guests make different Airbnb from hotels. (Guttentag and Smith 2017) confirmations that when evaluating their experience, Airbnb guests tend to use the same key practical attributes that they use to evaluate their hotel experience (comfort, cleanliness). Even with the various discussions, location, value, facilities, and hosts are the well-recognized attributes that involve an Airbnb experience (Luo and Tang 2019;Sainaghi 2020;Thomsen and Jeong 2021).

These studies are summarized in Table 1 and will be the framework for content analysis. Starting from category models already used in the literature guarantees the possibility of comparability with other studies, and when necessary, the categories can be adapted (Carlomagno and Rocha 2016).

|

Dimension | Conceptual definition | Relevant literature |

| Home benefits | The functional attributes of a home, including home environment, physical environment, and location | |

| Personalized services | Services (basic, personalized, and surprises) that hosts offer their guests | |

| Social interaction | Interaction between guest and host and among guests | |

| Authenticity | Sense of uniqueness derived from the local culture | |

| Economic benefits | Relationship between the listing’s perceived benefits and the monetary cost to use it | |

| Trust | Trust in the institution (Airbnb) and willingness to trust (hosts or guests) | Liang et al. (2018) |

Therefore,Table 1 identifies the dimensions related to user experience identified in previous studies and used in the coding and categorization: home benefits, personalized services, social interaction, authenticity, economic benefits, and trust.

2. RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

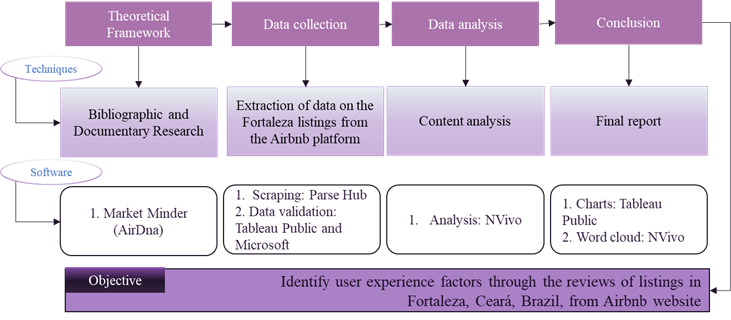

This research is applied, exploratory and descriptive, and adopts mixed methods framed by qualitative and quantitative analysis techniques (seeFigure 1).

In the first stage, the research was grounded on literature and documentary research of the concepts of Airbnb and user experience, present in existing materials such as scientific articles, books, and websites.

A search for data about the Airbnb platform in Fortaleza was also conducted in secondary sources. Due to the ease of access (payment of a subscription), the Market Minder platform[1] developed by AirDNA was selected. The platform features an interactive dashboard consisting of maps, charts, and adjustable filters, presenting various Airbnb metrics. For this research, information was collected about the number of listings in Fortaleza available on the platform, the type of place or accommodation, and their spatial distribution. The data was collected in February 2021 and included data up to January 2021.

In this research, the evaluations left by users on the platform were used as a source of data; in the context of research on user experience dimensions, most studies focus on analyzing the comments posted by users on online platforms (Tussyadiah and Zach 2017;von Hoffen et al .2018;Cheng and Jin 2019;Thomsen and Jeong 2021;Zhu et al. 2021). Thus, to identify the main associated themes, content analysis was used.Bardin (2016) states that content analysis is a set of tools to analyze communication, aiming to obtain a system of procedures and descriptive objectives of the messages from their content. This, in turn, allows understanding them in depth.

2.2. Data collection

Airbnb does not provide public access to its data, so data may be collected by querying the site systemically or through datasets available from private secondary sources such as Inside Airbnb (insideairbnb.com), Tom Slee (tomslee.net ) or commercial (paid). For Brazil, on the private sites, data is available for Rio de Janeiro, so it was decided to consult the data on the company's website. The data was collected from the Airbnb website using the Web Scraping technique, which extracts different, unstructured information from websites automatedly and represents the data into a coherent structure such as spreadsheets (Saurkar et al. 2018).

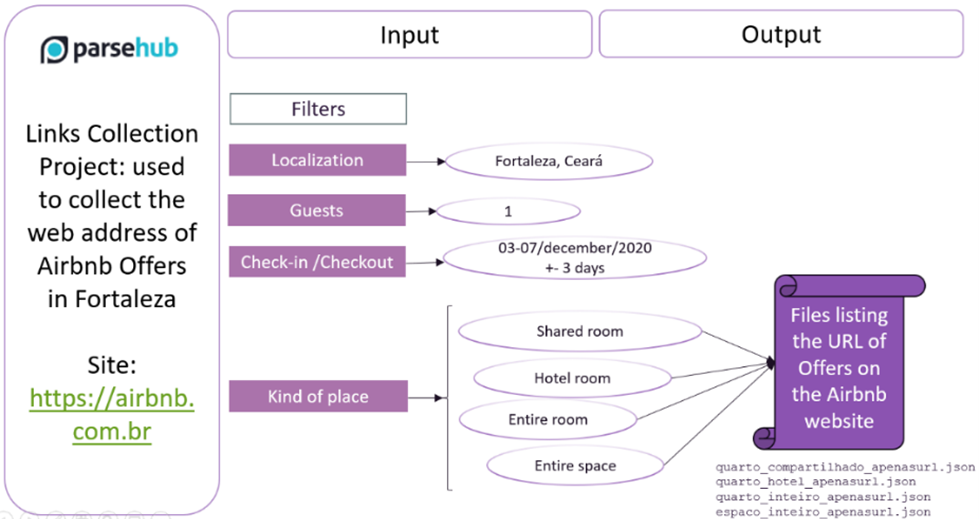

The tool used in this research was the Parse Hub[2] (it is free and easy to use), limiting the search to 200 pages. Due to this limitation (each Airbnb listing is a page that needs to be accessed, and Fortaleza has more than 200 listings), the strategy adopted was to create two projects in Parse Hub: one to collect the web addresses of the listings (Link Collection project) and another to extract the information from each listing (Data Collection project).

The first project was run four times, one for each type of place (shared room, hotel room, private room, and entire place), and each search generated a result file. These were grouped into a single file in XLSX format, treated by eliminating repeated listings, and then randomly split into eleven files containing subsets of web addresses to be used as input parameters for the second project, which aimed to collect specific data for each listing.

Figure 2 shows the filters used in the “link collection project”. The choice of filters and parameters used was made to return the greatest number of listings. The query period is a mandatory search field (as well as localization) and was used from December 03 to December 07, 2020. The “I’m flexible” date filter option was set for plus or minus three days to return more offers. No restrictions were applied to the price of the accommodation, nor the number of guests. After performing random queries of Airbnb offers between October/2020 and June/2021, this period was chosen, and the research period returned more offers.

The links extraction from the listings was performed on October 24, 2020, given to be a simple execution, and resulted in a list of web addresses that uniquely identify each listing. The “data collection project”, on the other hand, was performed between October 24 and 28, 2020, period in which each of the eleven files was submitted as input, Parse Hub accessed each Airbnb listing in Fortaleza and performed the data collection.

The data collected during this phase were description, location, host, superhost, daily rate, type, guests, rooms, beds, bathroom, ratings, overall average ratings, rating criteria (location, accuracy, value, cleanliness, communication, check-in) and the list of reviews (maximum of six) including guest name, date, and description.

All result files were imported into Tableau Public,[3]

a free software designed for analyzing and creating web-based interactive data visualizations. Dashboards with the collected information were cremated. The data[4]

were analyzed and validated.

A total of 2,537 user reviews associated with 682 listings were extracted. From this set, the listings that had no reviews, the invalid or incomplete reviews, and those posted between 2013 and 2018 were removed from the sample. At the end of the process, 2,338 reviews of 503 listings remained and were exported into a CSV file.

This file was then imported into Microsoft Excel to create four columns in the spreadsheet, namely: “location (group)”, “listing type (group)”, “guest gender” and “host gender”. After consulting the website, the researcher filled in this information. It was either incomplete at the origin (location and type of listing) or did not exist and had to be suggested (gender information).

Following the manual intervention, the XLSX file was imported into NVivo Plus version 12, which is used to assist in coding, categorizing, and interpreting the data applying content analysis. Word clouds were produced in the original language of the word captures in the Airbnb query; that is, although the word clouds are in Portuguese, the comments and content analysis were duly translated into English. This option was adopted because we understand that the original utterances should not be translated in discourse analysis. Thus, the discourse content in the original language generated an analysis that was translated into English.

2.3. Data analysis

For data analysis, content analysis was used. Content analysis can classify and categorize any content by translating its characteristics into critical elements that make it comparable to a set of other factors.Bardin (2016) proposes three stages to organize content analysis: pre-analysis, exploration, treatment, and interpretation.

The initial categories were configured as the first impressions about the comments, resulting in twenty-three categories in Table 2. Each category consists of factors selected from the comments and supports the theoretical framework. It should be noted that there are no rules for the naming of the categories or for determining the number of categories; such issues are contingent on the amount of data previously collected for the corpus (Silva and Fossá 2015).

Aiming to refine the data analysis, the progressive grouping of the initial categories resulted in the emergence of intermediate categories. These, in turn, support the construction of the final categories, the dimensions identified in the literature review (seeTable 1), that represent the synthesis of the meanings identified during the analysis of the study data. The progression of categories was built to support the coding, categorizing and analysis of data.

Finally, it is possible to compare the results with the theory, assigning meaning to the results and accumulating knowledge for the area of study, which will be presented in the next section.

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Consumer feedback through the reviews posted on the platform after using the service was used in this research as a source to measure Airbnb’s performance and understand customer needs and desires, as the use of text analytics can provide a better understanding of user experience in the context of hospitality.

Regarding the neighborhoods of the Airbnb listings collected for the analysis, they are Meireles (37.97%), Praia de Iracema (14.71%) and Mucuripe (7.55%), Centro (7.55%), Aldeota (5.17%), and Praia do Futuro I and II (2.58%). They are referred to here as tourist neighborhoods and are in line with the distribution of the accommodations in Fortaleza. However, besides the seven areas that account for 75.53% of the listings, Airbnb is capillary in forty-eight more neighborhoods, referred to as residential.

As for the 380 listings in tourist districts, the predominant type of accommodation is the entire place, totaling 262 (68,95%) of the places, whereas 110 (28.95%) are private rooms and eight (2.1%) are shared rooms. On the other hand, among the 123 listings available in residential neighborhoods, 92 are private rooms, i.e., 74.80% of all listings in residential areas offer this type of accommodation, whereas 27 (21.95%) are entire place and four (3.25%) are shared rooms.

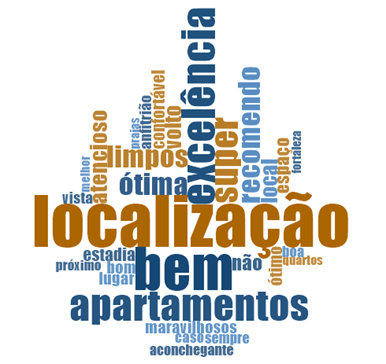

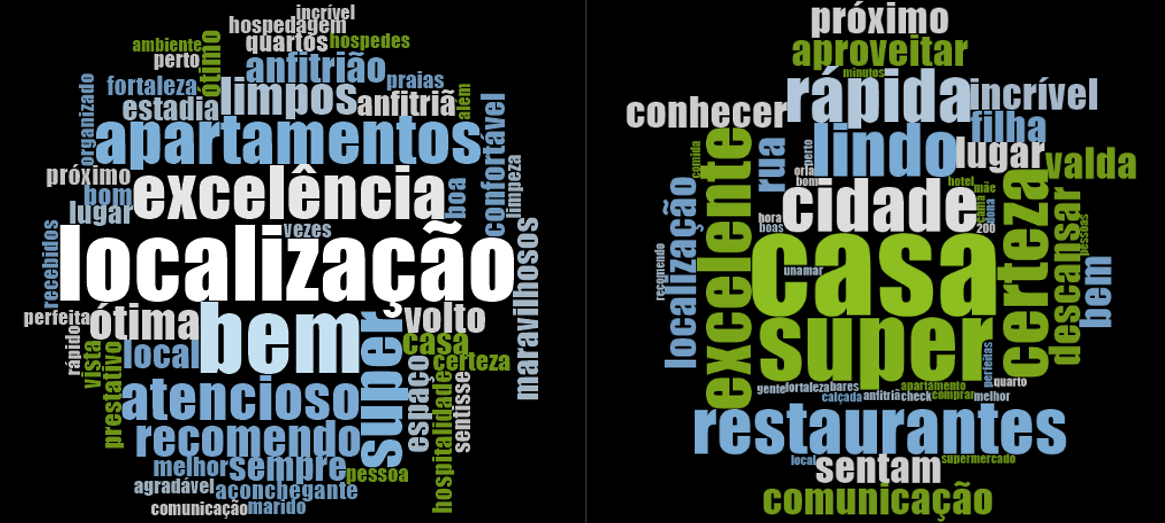

The word cloud provides a visual representation of the most frequent terms. Concomitantly to the definition of the categories, the thirty most frequently mentioned words in the reviews were listed, along with the corresponding words derived from the terms, with a minimum length of three characters. In addition, the main “stop words” were discarded, that is, terms that do not present helpful meanings to interpret the users’ discourse (seeFigure 4).

Location was the most cited term, showing that this category strongly influences the user experience. The words associated with this factor were “near”, “view”, “close”, as well as “beach” and “Fortaleza”.

The words “good” and “excellent” indicate a positive perception in the reviews and refer to subjective aspects and impressions expressed by adjectives such as “super”, “great”, “good”, “sure” and the verb “recommend”, all of which broadly indicate a sense of approval as well. In turn, the word “apartment” indicates that most listings offer apartments. Correlated to this term are the words “house”, “stay”, “space”, “room”, “local” and “place” as well as associations to the terms “cozy”, “comfortable” and “clean.

The words “host” and “hostess” are frequently used. However, many comments in the reviews section include the host’s first name, which cannot be associated with the query. Nonetheless, this seems to point out that hosts are cited in most comments left on the platform. The adjective “considerate” is potentially associated with hosts.

The most frequent derived words were “location”, “good”, “excellent”, “apartment”, “super”, “great”, “recommend”, “cleanliness”, “attentive” and “come back”.Thomsen and Jeong (2021), in a similar study in US cities, identified that the main themes of online user reviews were “cleanliness”, “location”, “stay”, “home”, “location”, “host”, “neighborhood” and “recommend”, indicating different priorities for users in distinct locations.

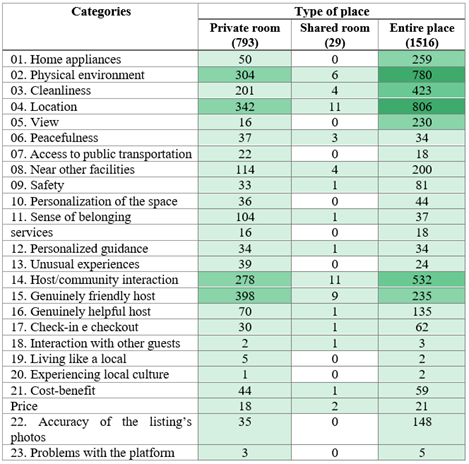

Regarding the number of reviews by type of place (seeTable 3), 1,516 (64.84%) comment on an entire place, 793 (33.92%) on private rooms, and 29 (1.24%) on shared rooms. As for the number of reviews of tourist and predominantly residential listings, 1,846 offer places located in tourist neighborhoods and 492 in residential areas.

The hierarchy of the categories was inserted in NVivo, starting from the broadest final category (dimension) to the initial category, for which three child nodes were created to identify polarity: positive, negative, and mixed. Then, the coding and categorization process was performed by selecting the entire evaluation but not the fragments. Thus, a rating could be assigned to different analysis categories, only sentiment polarity. For each rating associated with a category, a reference in the parent category was added, i.e., when categorizing a rating in two categories of the same dimension, NVivo adds two references to the parent category.

The initial categories “services” and “price” were created within the dimensions of home benefits and economic benefits in the coding and categorization process, and in the host interaction category, ratings that refer to interaction with the host’s staff were included.

According to the data, home benefits is the most relevant dimension, with 1,819 references, followed by social interaction, with 1,339 references, trust with 190 references, economic benefits with 144 references, and personalized services, with 126. On the other hand, the least characterized dimension was authenticity, with only nine references (see Table 4).

|

Dimension | References | Coverage |

| Home benefits | 1,819 | 77.80% |

| Personalized services | 126 | 5.39% |

| Social interaction | 1,339 | 57.31% |

| Authenticity | 9 | 0.38% |

| Economic benefits | 144 | 6.16% |

| Trust | 190 | 8.13% |

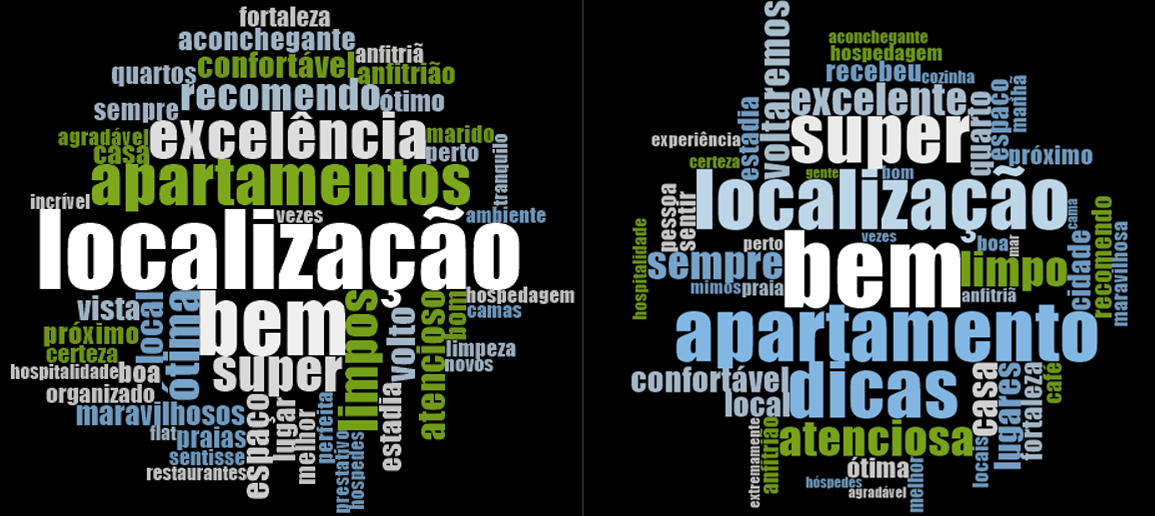

The most frequent terms in the reviews by dimension are presented below. For home benefits, they were “location”, “rooms”, “beds”, “apartments”, “flats”, “spaces”, “house”, “lodging”, “view”, “cleanliness”, “cozy”, “comfortable”, among others. For personalized service, the following words stood out: “tips”, “pampering”, “feeling”, among others, as shown inFigure 5.

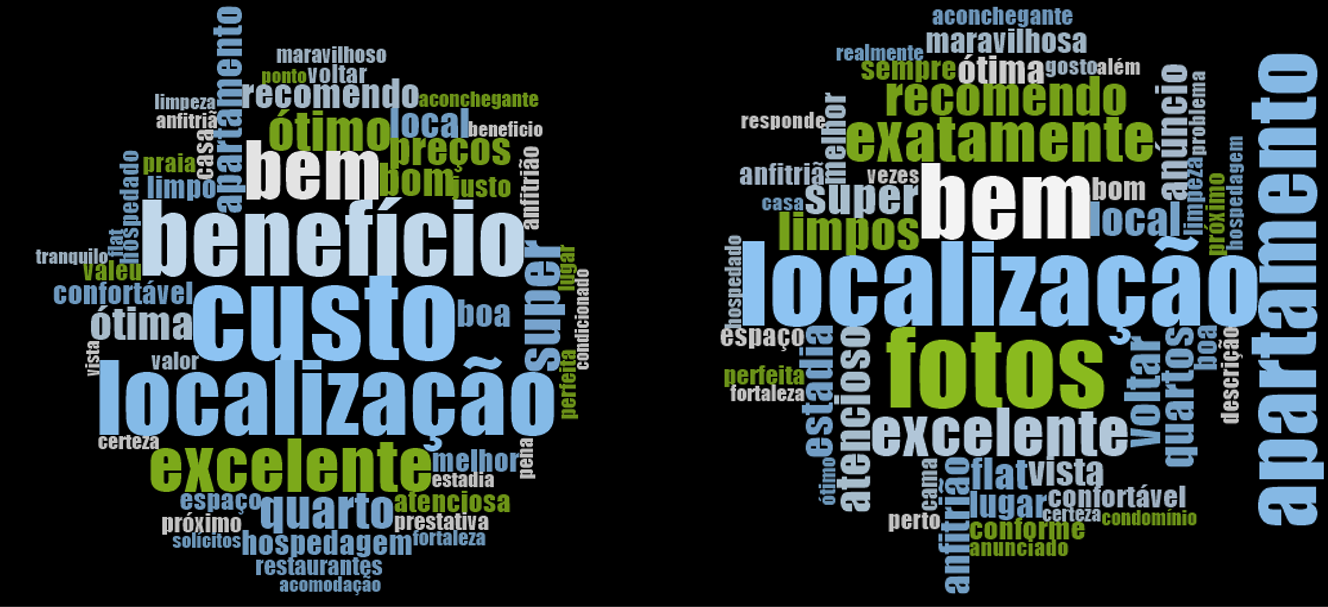

In the social interaction dimension, the following terms stood out: “host”, “hostess”, “welcomed”, “considerate”, “wonderful”, “helpful”, “communication”. For authenticity: “house”, “city”, “restaurants”, “street”, “place”, “know”, “enjoy” and “communication”, among others (seeFigure 6).

For economic benefits, “cost”, “price”, “value” and “benefit” stood out. Finally, for trust, the words were “photos”, “description” and “listing” (seeFigure 7).

Chart 1 shows the number of references and coverage at the category level grouped by dimension. The two most cited categories were “location”, mentioned in 1,159 reviews (49.57%), and “physical environment” in 1,101 (47.09%), both of which are associated with the home benefits dimension. These were followed by “interaction and communication with the host” with 825 (35.20%) mentioned in the reviews and “hospitable and friendly host” with 643 (27.50%) mentions, both of which are associated with the social interaction dimension. Next are the categories “cleanliness and organization”, “near other facilities”, “home appliances” and “view”. These eight categories were referenced in at least 10% of the reviews.

The finding that home benefits are the most highly rated dimension is in line with previous research.Guttentag and Smith (2017) consider that functional values such as home appliances and convenient location usually explain why customers choose Airbnb, andvon Hoffen et al. (2018) identify cleanliness, comfortable beds, fully equipped kitchens, space, a good view, a central and quiet location as the most valued aspects. Location, value, facilities, and hosts are well-recognized aspects in the Airbnb experience (Luo and Tang 2019;Sainaghi 2020;Thomsen and Jeong 2021). The importance of the social interaction dimension confirms the essential role of hosts in the hosting experience of Airbnb users (Ju et al. 2019;Ding et al. 2020), especially in establishing communication with Airbnb users, helping to foster an initial relationship of trust (Cheng and Jin 2019). Research also suggests that travelers demand unique experiences that involve meaningful interactions with locals (Tussyadiah and Pesonen 2016;2018). This aspect is consistent with the results of this research since the dimension social interaction was present in about 57% of the reviews.

Among the least referenced categories are “experiencing the local culture” with only three references (0.13%), “interaction with other guests” with six references (0.26%) and “living like a local” with seven (0.30%).

In turn,Li et al. (2019) have found that the Airbnb customer experience comprises four dimensions: home benefits, social connection, personalized service, and authenticity. However, for users visiting Fortaleza, the themes associated with customized service and authenticity showed no influence on the rating of the experience. For the authenticity dimension, the results corroborateSilva et al. (2021), who found that experiencing a destination as a local does not directly impact individuals’ consumption decisions. This finding identifies an opportunity to be explored by the accommodation sector in the city of Fortaleza.

Highlight for the view, peacefulness, and safety categories, which characterize aspects of the city of Fortaleza: concentration of listings on the beaches (view), tourist areas with the presence of restaurants, music (peacefulness) and public insecurity in some (safety).

For the entire place, the eight most rated categories are the same as those in the overall ranking shown inChart 1, although ranked in a different order. The three best-ranked categories were the exact, namely “location”, “physical environment” and “interaction and communication with the host”, the fourth most rated category was “cleanliness and organization”, the fifth was “home appliances” (seventh overall). The sixth was “hospitable and friendly host” followed by “view” and “near other facilities” (seeTable 5).

For the private room listing type, “hospitable and friendly host” is the most relevant category, indicating that the hospitality and friendliness of the host are the most relevant factors for guests seeking private rooms, followed by “location”, “physical environment” and “interaction and communication with the host”. The highlight is that the categories “home appliances” and “view” which ranked as the seventh and eighth most analyzed categories in the overall ranking, leave the top eight (top 8), while the categories “sense of belonging” and “genuinely helpful host” take their respective positions (seeTable 5), suggesting that guests who opt for shared accommodation with hosts tend to experience the local lifestyle.

For shared rooms, the categories “interaction and communication with host” and “location” come first, followed by “hospitable and friendly host” and “physical environment”; in fourth are “cleanliness and organization” and “near other facilities”; the new categories that come in seventh and eighth place are “peacefulness” and “price” and as with the private room type of offer, the categories “home appliances” and “view” do not seem to be relevant for the user experience (see Table 5).

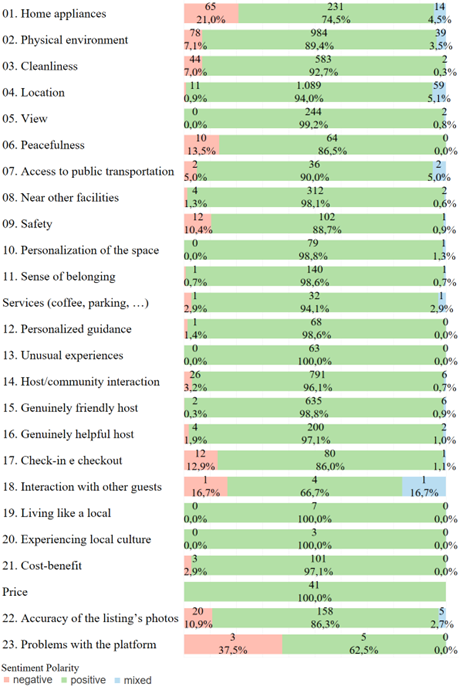

Analyzing through the prism of feeling, the categories with the highest percentage of negative reviews were “website problems” (37.5%), “home appliances” (21%), “interaction with other guests” (16.7%), and “peacefulness” (13.5%) (seeFigure 8). InGao et al. (2022), topics of Host, Location and Feeling at home associate with positive sentiment. enquanto os tópicos sobre Cheiro, Limpeza, Comodidades e Instalações no quarto tendem a ser negativos.

Conversely, the categories that received no negative mentions were “view”, “personalization of the space”, “unusual experiences”, “living like a local”, “experiencing the local culture” and “price” (seeFigure 8). InGao et al. (2022), topics on smell, cleanliness, amenities and in-room facilities tend to be negative. Já em Descobrimos que os tópicos Recomendar, Hospedar, Localização e Sentir-se em casa se associam a sentimentos positivos,

In the different empirical studies addressing this phenomenon, the importance of each Airbnb experience category varies, just as they have produced similar evidence, but some contradictory too.

Previous studies have found social interactions (guest-host) a core dimension of the Airbnb experience (Yannopoulou 2013;Tussyadiah and Pesonen 2016;Festila and Müller 2017).Yannopoulou (2013, 89) argues that Airbnb involves “meaningful life enrichment, human contact, access, and authenticity”.Guttentag and Smith (2017) claim that Airbnb users are attracted primarily by the practical attributes, while the experiential appeals are secondary. Even in the scope of the functional attributes, location was not statistically significant in influencing Airbnb users’ satisfaction, whereas enjoyment, amenities and cost savings were rated positively (in order of significance) (Tussyadiah 2016).

Some researchers suggest that the contradictory findings can be attributed to the lack of standardization of Airbnb accommodations (Tussyadiah and Zach 2017), and travel desires and different user personalities; for example, introverts may “travel to feel” whereas extroverts “travel to see” (Festila and Müller 2017).

Each city must develop different strategies according to the profile of its visitors. Knowing the experience allows stakeholders to improve the attributes that encourage positive reviews and impact the user experience.

CONCLUSION

In 2010, Airbnb entered the Fortaleza market, expanding the listings to lodging and accommodation users. This research has called attention to and broadened the understanding of this phenomenon, which is novel in the national and local tourism scenario and enabled the analysis of the experience of travelers visiting Fortaleza.

From a theoretical point of view, we list a series of categories that can be evaluated, compared, and better developed in future studies, so this study extends the existing research on services and hospitality, exploring the attributes of the user experience of Airbnb service in Brazil. The results can serve as a valuable reference for future comparative studies. Understanding which factors are relevant in user reviews and which aspects are considered during and after the stay brings practical implications for hosts to understand and improve their listings and expands knowledge so that their competitors can improve their services, focusing attention on the most relevant categories for the customer.A practical implication of the results of this study is the expected improvement in the quality of the offer deriving from innovation, which in turn derives from benchmarking between competitors (in this case, hosts). This is because Airbnb can consider the items most valued and use them as self-rating criteria for their hosts. In this same sense, it is also an opportunity for destinations to be ranked according to users' perceptions. Therefore, this first conclusion is directly related to the improvement in the quality of the offer.

By relating the constructs Airbnb and experience dimensions from content analysis, this study contributes to the scientific and business debates on the new forms of tourism consumption. It investigates part of the process involved in the guests’ experiences. Moreover, this study leads readers to reflect on the roles of the host, the platform, the community, and the consumer in this dynamic. All this because in the tourist experience hosts and visitors interact, both being responsible for the satisfaction with the experience. Thus, within this perspective of the collaborative economy, listening to users is essential to improve interpersonal relationships and, consequently, the quality of the offer.Finally, the results can also be used in planning and directing local public policies dealing with tourism destination development and urban city planning.

As for the tools and methods adopted in this research, the query was performed on the MarketMinder data platform; the listings data were collected from the Airbnb website using the ParseHub webpage data extraction technique; the data was treated using Tableau Public; finally, NVivo was used to support content analysis. At the end of the process, inferences and interpretations were made by correlating the results with the theoretical framework analyzed. The methodology met the proposed objectives and can be used in similar analyzes.

As for the most relevant factors and categories found in the content analysis, home benefits stood out as the most suitable, followed by social interaction, whereas the least essential dimension was authenticity. The eight most rated categories accounting for at least 10% of all ratings were “location”, “physical environment”, “interaction and communication with the host”, “hospitable and friendly host”, “cleanliness and organization”, “near other facilities”, “home appliances” and “view”. In turn, the least referenced categories were “experiencing the local culture”, “interaction with other guests” and “living like a local”. This finding indicates a gap in the promotion of strategies where the user can experience the local culture and have authentic experiences like a local, in addition, close contact between the host and the tourist makes all the difference. Furthermore, we conclude that Airbnb users in the city of Fortaleza do not consider the opportunity to live like a local relevant to their experience, and the user experience does not appear to be influenced by the gender of the guest. However, it was impacted by the type of listing and the location (i.e., tourist or residential neighborhood). However, it is essential to note that the influence of location on the user experience operates indirectly since the location is directly associated with the listing types; that is, entire place listings are concentrated in Fortaleza’s tourist neighborhoods, whereas private room listings are predominantly offered in residential neighborhoods.

The analysis of the reviews makes it possible to measure Airbnb’s performance and understand customer needs and desires and can provide a better understanding of user experience in the context of hospitality. Thus, the significant practical contributions of the study are aimed at showing the owners the essential categories from the point of view of tourists/customers. Another practical implication, now from the point of view of public management, is to make public managers understand that the season rental is an already consolidated form of accommodation. Therefore, the hosts must be considered “tourist entrepreneurs”. This modality should enter the planning of new policies, whether to improve the offer in tangible terms (category of home benefits) or intangible (category of social interaction/host hospitality).

Like most studies, this research has limitations. Therefore, potential developments to be addressed by future works have been identified. First, the number of reviews collected per listing was restricted to six due to limitations to configure the search tool. The second issue has to do with the number of listings collected, given that the initial proposal was to collect data from all listings in Fortaleza. However, this goal could not be achieved using the selected search tool. The third point to consider is that collecting demographic information about the guests has not been possible. Therefore, issues related to the sample population’s representativeness and the Airbnb customer experience across different generations could not be addressed.

We suggest that future studies compare guests’ experiences using Airbnb and hotels’ services that rely on online review systems to publish their listings to identify the similarities and differences in ratings on different platforms. The differences between the Airbnb experience in other cities in Ceará, Brazil, and the world can also be explored, reaching diverse cultures and regions. Using the methodological procedures proposed in this research, the line of research could be expanded. The same analysis can be applied to the Airbnb Experiences modality, which offers itineraries and tour services guided by locals. Finally, future research can investigate the Airbnb user experience from the perspective of value co-creation occurring between guests and hosts to see how and if hosts rely on the reviews posted by guests to identify potential improvements in the services they offer.