1. INTRODUCTION

Since we have begun to witness new tourism destinations that shape the way we choose our preferred tourism attractions, we began encountering new challenges and difficulties, particularly in the Middle East and specifically a country surrounded by an abundance of conflicts and disputes, such as Jordan. From a marketing point of view, the destination must hold a strong and positive image that ensures its popularity with tourists, as well as creating an accommodating atmosphere that positively influences both tourists' re-purchase and intention to recommend the destination to other tourists (El-Said and Aziz 2019). However, this image may be distorted by socio-political instability, national disaster, diseases and terrorism (Hughes 2008).

In Jordan, the tourism industry is considered as a paramount economic sector that contributed a considerable 7,632.8 million USD to its GDP in 2017 and was ranked as number 69 out of 185 countries worldwide by the World Travel and Tourism Council (WTTC) as of 2017. According to the same report, the Jordanian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities (JMTA) are hoping for the total contribution of travel and tourism to rise by 23.5% of GDP in 2028 to reach 13,563.6 USD Million (WTTC 2019). To achieve this, the tourists must perceive Jordan as a safe, secure and worthy detestation since, in making the decision to travel to a certain place; tourists must consider a multidimensional culture that involves a wide range of different factors (Farajat et al. 2017). Jordan as a tourist destination offers a wide range of cultural and natural touristic attractions, varying from the virtually untouched landscape of the protected area of Wadi Rum, to the ancient rosy-red city and designated UNESCO World Heritage Site of Petra, and the mineral lined shores of the Dead Sea (Al-Oun and Al-Homoud 2008;Liu et al. 2016). However, Jordan has recently been struggling with surrounding conflicts in neighbouring countries and is no stranger to disturbances. In particular, this region has experienced many extended conflicts over time such as the Arab Spring that started in 2010, the civil war in Syria that is still running to date, the on-going conflict in Iraq, the rise of the so-called Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) and the conflict between Palestine and Israel. Of course, the western media wouldn't leave all of these events without conveying, and therefore, the region where Jordan is located has been harmfully affected and the tourist perception will be so negative even though Jordan is still considered as a safe country. For example, a study byAhmed and Kadir (2013) confirmed that information sources especially the mass media negatively impacts the destination image particularly after events such as political instability. Nevertheless, Jordan is seen as one of the countries that have been affected indirectly by the terrorist threats and therefore has experienced many declines in the number of tourists and visitors (Farajat et al. 2017).

The European market for outbound tourist considered as one of the most important markets for the Jordanian tourism industry. According to the statistics, Jordan received about 3.5 million International tourists in 2018, about 700.000 of them were European tourists, and this number growing rapidly (Jordanian ministry of tourism and antiques 2018). The Jordanian ministry of tourism and antiques highlighted the growth in the number of tourists coming from the Asia-Pacific region, followed by tourist from Europe (Jordanian ministry of tourism and antiques, 2018). However, European tourists prefer to travel to safe and secure destinations and avoid destination that exposure to natural disasters, political usability, and/or terrorist attacks. In addition, they rely increasingly on social media and review sites as main sources of information in making their decision to travel to any specific destination (Country Brand Index 2018). In this case, a good marketing campaign is the one that meets their needs and preferences since this market offers a good opportunity to develop the tourism industry in many countries.

The works of literature support the fact that perception of risks and Tourism Destination Image (TDI) are playing a critical role in the tourists' behaviour and decision making (Kozak, Crotts and Law 2007;Sönmez and Graefe 1998a). Previous studies recommended more studies to integrate perceived risks and TDI as it was important for better understanding of tourism crisis and managing this crisis by alter negative perception and reinforce the positive one (Lepp, Gibson and Lane 2011;Qi, Gibson and Zhang 2009). In addition,Sönmez and Graefe (1998b) argued that it is important to understand the cognitive and affective processes individuals experience when they feel threatened. This relation between the perception of risks and TDI needs to be further investigated (Chew and Jahari 2014).

LITERATURE REVIEW

Destination image and tourists behavioural intention

Destination image is commonly accepted as an important aspect in successful tourism management (Molina et al. 2013). To be effective, destination marketers try to build strong and positive destination image that influence consumer perceptions of the destination.Milman and Pizam (1995) defined the destination image as the visual or mental impression of a place or a product experienced by the general public. The tourists are affected by the TDI that influence directly their decision-making process and their behavioural intention (Castro, Armario and Ruiz 2007).

Several previous studies found a direct relationship between the destination image and tourist behavioural intention. For instance,Bigne et al. (2001) found that TDI is a direct antecedence of tourists to visit and revisit intention and their intention to recommend the destination. Other studies byPrayag (2009) found that destination image has a direct impact on the tourist's behavioural intention. A study byPark and Njite (2010) showed that different destination image attributes significantly affect the tourist behavioural intention.Chen and Tsai (2007) proposed a more integrated tourist behaviour model by including destination image and perceived value into the ‘‘quality–satisfaction–behavioural intentions'' paradigm. The study found that the destination image has both direct and indirect effects on behavioural intentions. Amore recent study,Tavitiyaman and Qu (2013) studied the impact of TDI impact on the behavioural intention of travellers to Thailand. Their study found that the destination image indirectly influences behavioural intention through the tourist's overall satisfaction.Tavitiyaman and Qu (2013) study further discussed the impact of perceived risk on the tourist's behavioural intention and found that travellers with low perceived risk had a tendency for greater positive destination image, overall satisfaction, and behavioural intention than travellers with high perceived risk.

Components and formulation of destination image

It's argued that TDI is a combination of the product, behaviour and attitude, and the environmentMilman and Pizam (1995). Five dimensions of TDI proposed byTapachai and Waryszak (2000) based on consumption value theory. They suggested that functional dimensions like friendly local people, exotic food, historical sites, and beautiful scenery are the first tourism destination factor. The second factor is social dimension such as suitable for all ages. The third factor is the emotional dimension like relaxation and calm, while the fourth factor is the epistemic dimension such as different cultural climate. The last factor is the conditional dimension such as cheap travel and accessibility to the destination and other neighbouring countries.

The earlier work ofGunn (1972) identified that potential tourist regarding the absorption of information such as information from the news and movies to shape an organic image of the tourism destination which will motivation those to start gathering more information about the destination. After this stage of collecting information about the destination, the induced image will be formulated. The induced image of the destination is the image formulated in the potential tourist mined from receiving the tourism destination marketers advertising or any other activities to promote the destination.Fakeye and Crompton (1991) added the complex image which is formulated after the actual visit and direct experience with tourism destination. In this context, the present study focuses on the complex image (overall image) as the population of the current study is the European tourists who already visited Jordan. In this regard, the destination image is operationalized as an individual's mental representation of knowledge (beliefs), feelings and overall perception of a particular destination (Fakeye and Crompton 1991). In other words, it is the overall evaluative construct measuring tourists' holistic impression of Jordan as a tourism destination (Echtner and Ritchie 1993). Previous studies showed that complex image (overall image) serves as a strong proxy for capturing destination image (Prayag 2009; andPrayag et al. 2013).

Perceived risk and the tourists behavioural intentions

In general, the perception of risk used to describe a concept of people's attitude and intuitive judgments towards risk (Cui et al. 2016).Stone and Grønhaug (1993) defined it as a certain level of probability can be attached to risk to determine the probable loss. The perceived risk could also be defined as the probability that action may expose tourists to the danger that can influence travel decisions if the perceived danger is deemed to be beyond an acceptable level according (Reichel et al. 2007).Sönmez and Graefe (1998b) examined the issue of perceived risk and found it as a paramount important factor of avoiding travel to a destination perceived as risky. In tourism and travel studies,Roehl and Fesenmaier (1992) who pioneered the research on tourists risk perception, establish that perceptions of risks and travel behaviour appear to be specific to the situation, proposing that travellers perceive risks differently toward different destinations and thus, the need to study destination-specific risk perceptions.

The engagement of tourist's activities occurs for several motivations such as adventure, excitement, religious purposes, sports events and sometimes seeking novelty (Madden et al. 2016). The last thing the tourists want is to waste his valuable vacation time and to be in an unsafe destination; hence the perceived risk has become a pressing concern amongst tourists around the world. In addition, based on the fact that tourism industry is a service-oriented industry which is intangible and an experience in its nature, the tourism products and/or services are perceived riskier and susceptible to threats such as crime, socio-political instability, terrorists attack (Sönmez and Graefe 1998b), diseases (Rittichainuwat and Chakraborty 2009) and disasters (Tasci and Gartner 2007). This evidences force the potential tourist to make their decision to travel to the destination based on their perception and not the reality (Moisescu and Bertrea 2013) even though some times the perception differs from reality as the media plays a key role in forming consumers' risk perceptions through information dissemination of affected destinations (Roehl and Fesenmaier 1992).

From the marketing point of view, a safe destination or perceived safety consider as a pull factor, as well as a very important destination attributes that initiating travel desire (Matize and Oni 2014). As such, tourism destination managers attempt so hard to show that their destination is a risk-free place to visit since perceived risk found to have a significant impact in the pre-visit decision making by alerting rational decision-making pertaining to destination choice (Sönmez and Graefe 1998a). That means that potential tourists must perceive the destination as safe and protected against the danger posed by any non-desirable events and that what referred to as perceived safety.

Tourism destination risk dimensions

Researchers in tourism studies classified risk perceptions in several ways. For instance, an earlier study by Moutinho (1987) discussed the risks perceptions associated with travellers while making their travel decision and categorized it into four groups; these are war and political instability, health concerns, crime and terrorists attack. Five years later,Roehl and Fesenmaier (1992) identified seven types of risks like physical, financial, time, equipment, satisfaction, social, and psychological risks.Sönmez and Graefe (1998a) extended this work by adding risk factors that are likely to predict destinations to avoid such as health, political instability and terrorism. A study byTsaur et al. (1997) suggested that potential travellers could perceive the destination as unsafe to travel to for two factors, the first one is physical risk which is the possibility that an individual's health is at risk, injury and sickness, while the other factor is equipment risk which is the dangers arising from the malfunctioning of equipment, such as unsafe transportation. Researchers likeRittichainuwat and Chakraborty (2009) study factors that are not considered by other studies such as lack of novelty travel inconvenience, deterioration of tourist attractions. A more recent study byArtuğer (2015) focused more on the risks associated with terrorism and political instability and how these two factors impacting the traveller behavioural intention.Sohn et al. (2016) categorized it as physical risks and psychological risks. They argued that the person who performs tourist's activities could encounter individual events (illness or injury), environmental circumstances (warfare or weather) and social contact such as cross-cultural differences.Liu et al. (2016) conducted an extensive study in an attempt to answer the question of how risky is Jordan to travel to. Their study applied the Risk Perception Attitude (RPA) Framework in the context of tourism destinations. Originally, the RPA theoretical framework provides a comprehensive understanding of individuals risk perception attitudes which suggests that perception of individual's risk attitude is defined by perceived risk and efficacy beliefs (Rimal and Real 2003). However, their study was specific to the risk type of terrorism, hence they did not cover all types of risks that the potential tourists have in mind which will discourage them to visit Jordan apart from terrorism type of risk.

An important contribution to the understanding of risk perception related to tourism destination isPerpiña, Prats and Camprubí (2017) who have analysed the perceived risks in the context of international tourism. They argued that tourism experience could be affected by several risk factors whether natural and/or manmade events such as natural disasters, contagious diseases, wars and terrorist attacks. According toPerpiña et al. (2017) in the last two decades, different perceived risk study approached the perception of risk in a different way which resulted in a large number of different scales, typologies, and attributes. This results in confusion on how to conceptualize and operationalized risk perception in tourism research due to the lack of consensus on what elements to take into account when determining risk perception. Therefore,Perpiña et al., (2017) after reviewing 62 from 1997 to 2014 TDI and risk perception articles, included all possible aspects of risk that could be used in an instrument to assess this concept, and finally identified a 50 risk attributes that could suit to any tourism destination. From the 50 attributes,Perpiña et al. (2017) identified 5 factors of the risk perception associated with international travel; these are (1) physical risks, (2) destination risks, (3) value-time risks, (4) personal concerns and (5) inconveniences.

Researchers likeMitchell, Davies, Moutinho and Vassos (1999) argued that risk dimensions differ according to the type of tourism activities. For example, backpacker's tourists may not encounter the same type of risk factors as a leisure tourist experienced. Other claimed that risks perceived by potential tourists could be changed from time to time as well as from destination to another (Hasan et al. 2017). When tourists perceived the destination as an uncertain place to visit, this might impact the potential tourists' mind and discourage them from travelling to the destination or sometimes to the entire region (Fuchs 2013). Therefore, it is significant especially for tourism destination managers to understand what risks potential tourists perceive when they planning an international trip (Lehto et al. 2008).

After an extensive literature review in the perceived risks associated with tourism activities, a study byHasan et al. (2017) categorized it into six dimensions; these are a physical risk, financial risk, performance risk, social risk, psychological risk, and security risk.Fuchs and Reichel (2006) identified the same six types of risk associated with tourism destination, however, due to the difficulties of the interviewed tourists to distinguish between the psychological and social risks, Fuchs and Reichel combined these two types into a one risk type. As a result, the current study usedFuchs and Reichel (2006) five dimensions of perceived risks which are; perceived physical risk, perceived financial risk, perceived time risk, perceived socio-psychological and perceived performance risk.

Tourist's behavioral intentions

Generally, the intention is a subjective judgment about how we will behave in the future (Blackwell, Miniard and Engel 2001). According toZeithaml, Berry and Parasuraman (1996), future intention could be categorized into four categories; these are referrals, price sensitivity, repurchase, and complaining behaviour. An earlier study byFishbein and Ajzen (1975) described the behavioural intention as the function of evaluative beliefs, normative beliefs, and situational factors that can be anticipated at the time of the vacation plan or commitment. In the tourism literature, tourist's behavioural intention is the tourist's planned future action (Barlas, Mantis and Koustelios 2010) and can be described as an intention to return and willingness to recommend the destination to others (Lončarić et al. 2016;Castro et al. 2007).

Some of the earlier studies argued in favour of measuring the tourist's behavioural intention by looking at their intention to revisit suggesting that revisit intention is the main element of behavioural intention. For instance,Thiumsak and Ruangkanjanases (2016) argued that the intention to revisit is one of the most significant consequences of tourist's participation. However, due to the fact that tourism is a service-oriented industry which is intangible in its nature, and the tourists can't evaluate the service before buying it, the tourist's behavioural intentions will differ accordingly (Lončarić et al. 2016;Litvin, Goldsmith and Pan 2008). We can't say that the repurchase intention is the only predictor for behavioural intention. That is because many potential tourists seeking novelty and therefore their intention to recommend the destination to others and separate a positive Word-Of-Mouth (WOM) reflect good indicators for their behavioural intention (Phillips, Wolfe, Hodur and Leistritz 2013). Previous studies consider WOM as a significant information source in making a purchase decision (Vincent 2018;Confente and Russo 2015), important marketing tool (Bao and Chang 2014), essential when the service is complex (Zeithaml 1988), and a critical information source especially when the service has a high perceived risk (Litvin, Blose and Laird 2005). As such, the present study argued in favour of measure tourist's behavioural intention by looking at both factors which are; revisit intention and the willingness to recommend the destination.

RESEARCH HYPOTHESES

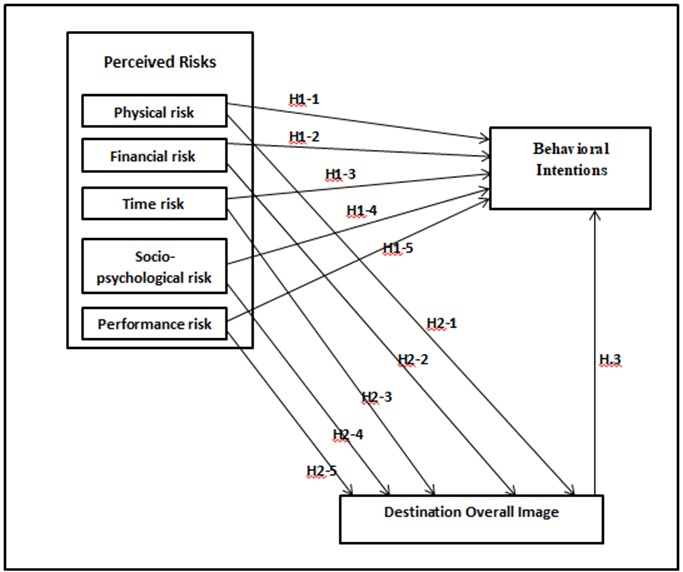

Based on the theoretically accepted knowledge mentioned above, the current study estimate that perceived risks dimensions related to Jordan as a tourism destination has an impact on the overall image of and tourists behavioural intentions. In addition, this research considering that the destination overall image had an impact on tourists behavioural intentions. Thus, the current study proposed the following hypotheses:

H.1: Perceived risks impact the tourist's behavioural intention.

H.1-1: Perceived physical risk impacts the tourist's behavioural intention.

H.1-2: Perceived financial risk impacts the tourist's behavioural intention.

H.1-3: Perceived time risk impacts the tourist's behavioural intention.

H.1-4: Perceived socio-psychological risk the tourist's behavioural intention.

H.1-5: Perceived performance risk impacts the tourist's behavioural intention

H.2: Perceived risks impact the overall destination image.

H.2-1: Perceived physical risk impacts the overall destination image.

H.2-2: Perceived financial risk impacts the overall destination image.

H.2-3: Perceived time risk impacts the overall destination image.

H.2-4: Perceived socio-psychological risk impacts the overall destination image.

H.2-5: Perceived performance risk impacts the overall destination image.

H.3: Destination overall image impacts the tourist's behavioural intention.

METHODOLOGY

Data collection

The present study intended to examine the impact of perceived risks and overall tourism destination image on European tourist's behaviour intentions directly after their visit to Jordan in 2018 (June 2018-August 2018). The study used a purposive sampling method since the accurate size of the population cannot be ascertained. Trained researchers assistances approached the European tourists while they are waiting to leave Jordan through its major Queen Alia International Airport (QAIA) on the basis of face-to-face. The trained researchers targeting the respondents that meet the following inclusion criteria: (1) European tourists, (2) visiting Jordan for tourism activities, (3) over 18 years (Mill and Morisson 2002). A self-administered survey was conducted as a data collection technique.Özdamar, (2003) suggested as a minimum of 550, andVeal (2006) stated that the sample size of 10,000 populations equals 370 sample units and 500,000 and above equals 384. Hence, a total of 400 questionnaires were distributed among European tourists. Taking into consideration the incomplete, erroneous and not returned survey, out of which 339 were usable for analysis resulting in a response rate of 85 %.

Study Instrument

As the study sample was the European tourists, the questionnaire was ready in four languages; these are the original English version, German, French and Russian translated by professional translators and retranslated back to English to assure the accuracy of meaning.

The final version of the questionnaire comprised of 26 items structured into four parts. The first part presents the respondents'' socio-demographic variables such as nationality, age, gender, income and education via a categorical scale. In the line with the previous literature review, the second part consisted of 20 items related to perceived risks derived from five risk dimensions adopted fromFuchs and Reichel (2006) study who adopted and tested it from the previous work ofRoehl and Fesenmaier (1992). These five dimensions are perceived physical risk, perceived financial risk, perceived time risk, perceived socio-psychological and perceived performance risk. The second part of the questionnaire contained 5 items regarding the tourist's behavioural intentions adopted from earlier work ofPike et al. (2010) andHuang and Hsu (2003). The scales for the perceived risk dimensions and tourists behavioural intentions were measured by means of a five point-Likert scale with anchors ranging from (1) strongly disagree to (5) strongly agree. The last part contained a single question regarding the overall destination image. The last section of the questionnaire is a single item anchored on 5-points scale rating from (1- unfavourable) to (5- favourable) used to measure the overall image of Jordan as a tourism destination. Respondents asked to answer the following question "How would you describe your impression (the overall image) of Jordan as a tourism destination". This method of measuring the overall image of the tourism destination is largely used in previous studies (Bigne et al. 2001;Beerli and Martin 2004a). These earlier studies argued in favour of using this method as the destination image has been described as an overall impression greater than the sum of its parts (Fakeye and Crompton 1991;Beerli and Martin 2004b;Prayag et al. 2013) rather than using former approach which is sum of all attributes (Echtner and Ritchie 1993) that omitted some of the relevant destination attributes (Castro et al. 2007;Prayag 2009).

Originally, the scale of the current study contained 35 items. However, based on recommendations and feedback from tourism experts and four academicians in Irbid National University, the questionnaire statements were modified to fit the context of the present study. Additionally, before conducting the study, the pilot test on 20 postgraduate tourism management students was conducted to assess how well each scale captured the construct it was supposed to measure. Items that loaded less than 0.40 should be deleted as suggested byHair et al. (2006). The findings of the reliability tests for each variable showed that Cronbach's alpha was above .70 which is considered satisfactory for exploratory studies. More specifically, results in terms of reliability analysis, first in "Perceived Risks Scale" Cronbach, α = .90, among "Perceived physical risk" factor Cronbach, α= .82, "Perceived financial risk" factor Cronbach, α = .85, "Perceived performance risk" factor Cronbach, α = .84, "Perceived time risk" factor Cronbach, α = .78, and "Perceived socio-psychological" factor Cronbach, α = .79. Second part is "Behavioural Intention Scale" Cronbach, α = .86. Finally, "Destination Overall Image" was measured using a single item, and as such, the reliability is difficult to be measured. In this case, the researchers count on test-retest reliability where the same question administered to the same sample at two points in the time and correlate the scores for an estimate. As a result, the questionnaire was subsequently refined to improve understanding.

FINDINGS

Demographic profile of the respondents

The table below shows the demographic profile of the respondents. Out of the 339 participants, the majority of respondents were female representing 57.2 %. The majority of the age group was respondents of age between 26 to 40 years consist of 44.9%. The majority of the respondents were with bachelor's degree representing 43.9%. In terms of monthly income, 46.1% of the respondents failed in the category of 1500 - 3000 euro per month. The top three Europeans nationality visiting Jordan were Russia (14%), UK (13%), and Germany (10%). Finally, about 70% of the respondents using the group packed tour as their travel arrangement method.

Descriptive statistics

In the following section, the results of the descriptive statistical test of the study variables will be discussed. In terms of the average value of the sample towards the physical risk they perceived in Jordan, the European tourists have medium to low average value regarding the physical risks perceived during their visit to Jordan (general arithmetic mean was 2.4). The arithmetic means ranges from (2.1) in their least limit for the paragraph "There are infectious diseases (H1N1 Influenza, HIV etc.) in Jordan." to (3.8) in their highest limit for the paragraph "The Jordanians does not receive my behaviour very well including the way I customarily dress " on a Likert 5-point scale, with 5 being strongly agree. However, they still agreed that some of their behaviours are not accepted by the local people. In case of the attitudes of the sample towards the financial risk they perceived in Jordan; the general arithmetic mean was very high and reached (4.4). The European tourists strongly believe that holiday in Jordan is more expensive than any other holiday and they do not think that they received sufficient service for the amount that they paid (value of money) for their holiday on a Likert 5-point scale, with 5 being strongly agree.

In terms of the attitude of the sample towards perceived performance risk, the general arithmetic mean was low reaching (2.4). They strongly believe that local people in Jordan are very friendly, and the food in Jordan is very good. However, they still consider that accommodations in Jordan aren't satisfactory in terms of service quality.

Regarding the Socio-psychological risk perceived by European tourists during their visit to Jordan, the general arithmetic mean was low reaching (2.1). European tourists perceived Jordan as a good destination that suits their personality and the holiday in Jordan will not change their family and friends options about them. Finally, the general arithmetic value mean of the sample towards perceived time risk was relatively low (2.7) ranges from (2.1) in their least limit for the paragraph "In general, I think that my holiday in Jordan is a waste of time " to (2.9) in their highest limit for the paragraph "I think that my holiday plan and program in Jordan is a waste of time". It could be concluded that European tourists think that their vacation in Jordan was not a waste of their valuable vacation time.

Regarding the overall image of Jordan as a tourism destination, the respondents were asked to answer the single question of "How would you describe your impression (the overall image) of Jordan as a tourism destination" that anchored on 5-points scale rating from (1- unfavourable) to (5- very favourable). The result shows that European tourists have a favourable overall image of Jordan as a tourism destination with general arithmetic mean reaching (3.6). This describes a good value for the tourism destination but not very high. This could be due to the unsatisfied tourists about the high prices in Jordan especially when they feel they did not get value for their money.

In terms of the European tourist's intention to revisit Jordan in the future as well as their willingness to recommend the destination to others (tourist's behavioural intention), the general arithmetic means reached (4.0). This high mean value shows that respondents will plan to revisit to Jordan in the future as well as encourage and recommend Jordan as a tourism destination to others. The highest limit for the behavioural intention paragraph was for the "I will encourage friends and relatives to visit Jordan" with arithmetic mean reaching (4.4).

Correlation analysis

The computation of the Pearson Correlation Coefficients was performed. Pearson correlation is the same zero-order correlation as the aim in this section was only to understand the relationship between the study variables without controlling for the influence of any other variables.

Correlation analysis was conducted on the data of the survey based on the independent variable of overall tourism destination image and perceived risk dimensions (perceived physical risk, perceived financial risk, perceived time risk, perceived socio-psychological risk, and perceived performance risk) against the dependent variables of tourist's behavioural intention. Correlation is significant when the value is less than (0.05) which means the interactions between variables could be analysed. The result showed that all perceived risk dimensions in the research model are negatively and significantly correlated, which means that as risk dimensions decreased, the tourist's behavioural intention to revisit and recommend Jordan as a tourism destination to others will increase. A majority of the correlation values of the variables showed correlations coefficients with values below 0.68 and in the expected direction. A strong correlation has been found between financial risks and tourist's behavioural intention (r =0.67) followed by strong correlations between the perceived physical risk and perceived time risk with tourist's behavioural intention with the correlations of (r = 0.60) and (r = 0.59) respectively. However, low correlation has been found between perceived performance risk and socio-psychological risk with the tourist's behavioural intention with the correlation of (0.13) and (0.11) respectively. In addition, the result shows overall tourism destination image and the tourist's behavioural intention are positively and significantly correlated, however, a weak affiliation between these two factors with the correlation of (0.12).

Hypotheses testing

The multiple regressions were used to test the hypotheses of the study as there is more than one independent variable affecting the dependent variable. The interruption of the regression analysis is based on the standardized coefficient beta, R square and if its calculated value was higher than its tabulated value that provides evident whether to support the hypotheses stated earlier. It is suggested that if measurement scale of independent variables are same, the results of the analysis for both methods (standardized and un standardized coefficient) will be the same. However, standardized coefficients are more useful in comparison of impact of any independent variable on the dependent variable. Since regression analysis is very sensitive to outliers, standardized residual values above 3.0 or less than 3.0 were deleted by casewise diagnostic in the regression analysis in SPSS package.

In order to test the hypotheses H.1-1, H.1-2, H.1-3, H.1-4, and H.1-5, multiple regression analyses were undertaken between destination perceived risks dimensions and the tourists' behavioural Intention. In this analysis, destination perceived risks dimensions (perceived physical risk, perceived financial risk, perceived time risk, perceived socio-psychological risk, and perceived performance risk) were treated as the independent variables, whereas the tourists' behavioural Intention was treated as the dependent variable. From the first run of the test, the casewise diagnostics indicate that observation number 70, 55, and 219 found to be outliers and hence deleted in the next regression run. The value of calculated F is higher than tabulated F value at the confidence level (α≤ 0.05), and the value of statistical significance level is (0.000) which is less than the value of the confidence level (α≤ 0.05). The F-statistic (F= 16.556 p< 0.001) indicates that the relationship between independent and dependent variables is significant. The R square obtained for the five perceived risk dimensions rating means that about the 24% in the tourists' behavioural intention can be explained by the tourists' perceived risk dimensions (R²=0.237). That is, 24% of the change in the degree of tourist behavioural intention can be explained by the five perceived risk dimensions that are included in the regression equation. The multiple regression analysis showed that two of the dimensions included in the regression equation emerged as significant predictors. These are perceived financial risk (r= 0.194) and perceived performance risk (r= 0.217, p<0.001) which had significant relationships with tourists behavioural intention. In contrast to the hypotheses, the result indicated that perceived physical risk (β= 0.071), perceived time risk (β= 0.088), and perceived socio-psychological risk (β= 0.069) were not significant with tourist's behavioural intention (p > 0.001). Thus, hypotheses H1-2 and H1-5 were supported while H1-1, H1-3, and H1-4 were not accepted. Based on the size of beta values, the predictor's variables exercising the most influence on tourists behavioural Intention was perceived performance risk (β= 0.023), followed by financial risk (β= 0.019). It is important to note that the tolerance and VIF values shown in the output indicate that no multicollinearity effect among the independent variables on dependent variables.

In order to test the hypotheses H.2-1, H.2-2, H.2-3, H.2-4, and H.2-5, multiple regression analyses were undertaken between destination perceived risks dimensions and the overall destination image. In this analysis, destination perceived risks dimensions (perceived physical risk, perceived financial risk, perceived time risk, perceived socio-psychological risk, and perceived performance risk) were treated as the independent variables, whereas the overall destination image was treated as the dependent variable. >From the first run of the test, the casewise diagnostics indicate that observation number 11, and 21 found to be outliers and hence deleted in the next regression run. The value of calculated F is higher than tabulated F value at the confidence level (α≤ 0.05), and the value of statistical significance level is (0.000) which is less than the value of the confidence level (α≤ 0.05). The F-statistic (F= 14.221, p< 0.001) indicates that the relationship between independent and dependent variables is significant. The R square obtained for the five perceived risk dimensions rating means that about the 13% in the tourists' behavioural intention can be explained by the tourists' perceived risk dimensions (R²= 0.131). That is, 13% of the change in the degree of the overall destination image can be explained by the five perceived risk dimensions that are included in the regression equation. The multiple regression analysis showed that two of the dimensions included in the regression equation emerged as significant predictors. These are a financial risk (r=.231) and perceived performance risk (r= 0.207) which had significant relationships with overall destination image. In contrast to the hypotheses, the result indicated that perceived physical risk (β= 0.055), perceived time risk (β= 0.084), and perceived socio-psychological risk (β= 0.077) were not significant with overall destination image (p > 0.01). Thus, hypotheses H.2-2 and H.2-5 were supported while H.2-1, H.2-3, and H.2-4 were not accepted. Based on the size of beta values, the predictors' variables exercising the most influence on the overall destination image was a financial risk (β= 0.21), followed by perceived performance risk (β= 0.14). It is important to note that the tolerance and VIF values shown in the output indicate that no multicollinearity effect among the independent variables on dependent variables.

The overall image of Jordan as tourism destination when regressed against the tourist's behavioural intention, the result showed that only 9 % of the variance in the tourist's behavioural intention could be explained by overall destination image (R²= 0.004). The results also indicated that the overall destination image had a positive and significant effect on tourist's behavioural intention (r= 0.155). Thus, hypothesis H.3 was supported.

DISCUSSIONS OF RESULTS

As Jordan located between Palestine, Israel, Egypt, Iraq and Syria, the image of Jordan as a tourism destination has been negatively affected in the last two decades (Liu et al. 2016). The present study provided empirical evidence examining the effects of destination overall image and perceived risk dimensions on the European tourists' behavioural intentions. The findings pointed out that both perceived financial risk and perceived performance risk had a significant effect on the overall image as well as the tourist's behavioural intentions. The current study findings were in line with the findings byAl Muala (2010); andSchneider and Sonmez (1999) which previously studied the destination image of Jordan as a tourism destination. In addition, the overall destination image found to have a significant impact on tourist's behavioural intentions. The findings of this study concurred with a previous study ofHarahsheh (2010). It was not surprising that perceived physical risk associated with Jordan as tourism destination had no effect on tourist's behavioural intentions. After their visit to Jordan, the tourists experienced a safe and secure tourism destination, hence, perceived physical risk appeared not to be important to the tourists who were there as it was found byFuchs and Reichel (2011); and a study byHarahsheh (2010) previous studies. The study indicated that European tourists found Jordan as expensive tourism destination where they did not receive value for their money (mean 4.4). They strongly believe that a holiday in Jordan is more expensive than any other holiday (mean 4.5). This could be due to the fact that Jordan is a poor country where its main income comes from taxes that the government implemented on service and products especially the touristic one. For example, the Economist Intelligent Unit ranked Amman as the most expensive city in the Arab world in 2015 (Jordan Times 2015).

The physical risk of the European tourists perceived in Jordan was one of the current study concerns. In general, the European tourists have medium to low value regarding the physical risks perceived during their visit to Jordan (general arithmetic mean was 2.4). However, they still agreed that some of their behaviours are not accepted by the local people. This could be due to the fact that Jordan is a Muslim country whereas most of the European tourists are Christians and have different religion and cultures. The majority of the respondents agreed that Jordan considers as safe and secure tourism destination to be visited and recommended, hence, there is no worry about snatching, terrorism, and are infectious diseases.

The study found that financial risks associated with Jordan as tourism destination had a negative and significant effect on the European tourist's behavioural intention. That is, the less the perceived financial risk, the more they are willing to revisit and recommend the destination. Similarly, the study found that financial risks associated with Jordan as tourism destination had a negative and significant effect on the European overall destination image. That is, the less the perceived financial risk, the more they will have a more favourable image of Jordan as a tourism destination.

As for the perceived performance risk, European tourists found the local people in Jordan offering a friendly environment. However, they still believe that accommodations in Jordan aren't satisfactory in terms of service quality. They also addressed certain issues such as public transportation and cleanliness that need to be improved and expeditiously by the industry. This could be related to the earlier mentioned the value of money where tourists pay a good amount of money in five stars hotels or resort and expected the quality of very high service. It should be mentioned here that Jordanian hotels and resorts are dominated by high-end five stars and very few budget or midlevel hotels are available. In addition, the European tourists are known as a segmented market that is highly sensitive to the quality of service and variety of options offered, therefore lack of food and accommodation options at several prices will discourage them from visiting Jordan. This was confirmed by the current study as a negative and significant effect of the performance risk on the European tourist's behavioural intention. Furthermore, the present study found a significant relationship between perceived performance risk and overall tourism destination from the perspective of European tourists.

The findings correspondingly indicated that the three risk dimensions (perceived physical risk, perceived time risk, and perceived socio-psychological risk) had no significant effect on both overall destination image and European tourists behavioural intention. Finally, the current study confirmed the significant impact of tourism destination overall image on the behavioural intention. That means, the more the current tourists have a favourable image of the destination that they visiting, the more they are willing to revisit it in the future as well as recommend it to others such as their friends and family.

CONCLUSION

As suggested in the literature, tourists rely more on the destination image when they are deciding a tourist destination; in addition, they have a big concern about the quality of the services they will get during their visit (perceived performance risk), as such, tourism services providers in Jordan should double their effort regarding offering high-quality tourists' experience to ensure that tourists will gain valuable experiences during their stay. Providing a variety of accommodations and places to eat and not only a five-star services that European tourists perceived it as expensive and not a value of money. It is very difficult to sell Jordan if it is seen as a pricy destination by many of the European tourists and tour operators. It is recommended therefore that Jordanian government should reduce the taxes that the implemented on the touristic services and produces such as hotel, transportations, food and beverages, and entrance fees at tourism destination attractions in order to make Jordan more price competitive rather than ones that have the opposite effect. This study provided several contributions. Firstly, the results of examining the relationship between these factors will assist a destination with future marketing campaigns designed to increase market share by correct the negative perceptions and reinforce the positive perceptions. In addition, few studies -to the best of the researcher's knowledge- have examined the relationship between destination image, perceived risk, and intention to travel especially in the case of European travellers to Jordan. Secondly, some researchers criticized the exciting theories as it does not take into consideration variables like perceived risks in the tourism destination selection process.Roehl and Fesenmaier (1992) who pioneered the research on tourists risk perception, found perceptions of risk and travel behaviour appear to be specific to the situation, proposing that travellers perceive risks differently toward different destinations and thus, the need to study destination-specific risk perceptions. For example, a study byChew and Jahari (2014) addressed the radiation risk and its influence on Japan as a tourism destination image, such risk cannot be applied on the case of Jordan as a tourism destination. Therefore, it was essential to conduct a study that sheds the lights on of risk-related perceptions among European potential tourists. Thirdly, studying tourist's behaviour intentions whether by their desire to revisit or their willingness to recommend the destination and separate positive WOM is very essential as it can help to forecast whether the target customers will become long-term customers and bring more profits to the enterprises by building up an attractive destination image and expand their marketing effort to maximize their use of resources (Su and Fan 2011). Finally, the population of the present study is the European tourists who visited Jordan and getting ready to go back to their countries, therefore, this study inspects tourists' perceptions of relevant and real risks instead of general assessments which consider as an important strategy to develop and recover the TDI. As a final point, this study had some limitations could be considered for further research. Firstly, the findings of the present study were based on a sample of European tourists who visited Jordan and getting ready to leave back, future research could focus on different segment market such as tourists from Asia and the Middle East. In addition, future research could be conducted not only on the tourist who leaving, but also in two time lags (by their arrivals and by their leaving). Secondly, the method of measuring overall destination image of Jordan used in the present study was based on one single item anchored on 5-points scale rating from (1- unfavourable) to (5- favourable), future research could take into consideration measuring the overall destination image using multiple items that included all specific destination attributes. Thirdly, the study data have been collected in summer, if different study gathered the data in different season (e.g. winter) that might lead to have better results. Finally, future study could divide repeated visitors from the first time visitors as the visitors perceptions of the destination may differ within the two groups. |