INTRODUCTION

In a highly competitive scenario, loyalty has become a strategic goal for destinations, and a clear indicator of success (Ribeiro et al. 2017). Loyalty reduces advertising and promotion costs, provides an effective indicator of tourist satisfaction and is a key factor in determining destination feasibility (Kanwel et al. 2019). As a result, numerous studies have addressed the question of loyalty determinants. The principal determinants for loyalty include satisfaction, perceived quality, motivation or destination image (Khasawneh and Alfandi 2019;Suhartanto et al. 2019;Vo and Chovancová 2019;Almeida-Santana and Moreno-Gil 2018;Hapsari 2018;Antón, Camarero and Laguna-García 2017).

In recent research attention has focused on visitor perception of certain aspects of the destination in order to describe tourists’ behaviour and loyalty, considering determinants such as the tourist-resident relationship, sustainability or fairness (Brščić and Šugar 2020;Hwang, Baloglu and Tanford 2019;Moliner et al. 2019;Lai, Hitchcock and Liu 2018;Kim 2017;Iniesta-Bonillo, Sánchez-Fernández and Jiménez-Castillo 2016). These studies concluded that in many cases visitor perception in these areas has the capacity to generate memorable tourism experiences, and also conditions satisfaction and loyalty levels.

Perceived ethics of destination appear implicitly in a number of studies that analyse destination image and tourists’ behaviour (Fan, Zhong and Zhang 2012;Mcdonald 2015), but little research has assessed the importance ethical aspects play in loyalty from an integrated approach. On the other hand, the number of studies into tourists’ behaviour in South America is limited and to date no research appears to have considered tourist loyalty in Ecuador from an integrated approach. To bridge these gaps, our study focuses on Quito and considers the notion that perceived ethics of destination may condition tourist loyalty.

For the purpose of our study, loyalty refers to the intention to return to the same destination and the positive impact of word-of-mouth (WOM) on friends and/or relatives. Our research proposes a model capable of testing the effects of perceived ethics of destination, perceived trip quality and satisfaction as predictors of loyalty, as well as examining the relationships between predictors. Although Quito, the capital of Ecuador was the city chosen for our analysis, the findings are potentially applicable to other heritage cities in other regions of the world. Our work makes two further contributions. On the one hand, it advances the current understanding of tourists’ behaviour and provides a basis for further literature addressing the question of loyalty. Furthermore, considering the key role loyalty plays in destination competitiveness, the findings could be of use to tourist destination managers in boosting tourists’ loyalty.

2. CONCEPTUAL BACKGROUND AND HYPOTHESES

2.1. Destination loyalty

Loyalty can be considered from a behavioural or an attitudinal standpoint. In the former case, it refers to repeat visits and the frequency with which they occur (Yoon and Uysal 2005), whilst in the latter case, loyalty is understood as the intention to return and/or recommend the destination to others (Zhang et al. 2014). It is this vision of loyalty that is most commonly used in measuring tourist loyalty (Ribeiro et al. 2017) and will therefore form the focal point of our study.

Visitor loyalty is considered a key determinant for the overall success of a destination and in particular of any business operating therein (Akhoondnejad 2016). On the one hand, loyal repeat visitors to a destination provide a stable source of revenue. Furthermore, attracting these visitors who are already familiar with the destination is cheaper in terms of promotion and marketing strategies. In addition, these loyal visitors have a lower price elasticity and would therefore be prepared to pay higher prices. Finally, they are themselves providers or positive word-of-mouth publicity (Kanwel et al. 2019). Taking all these factors into account, it would seem clear that generating visitor loyalty is a key strategy for heritage cities acting within a highly competitive context.

The determinants of tourism loyalty have received a considerable amount of attention from scholars. A review of the major publications over the last decade reveals that the principal determinants addressed include touristsatisfaction (Antón, Camarero and Laguna-García 2017;Kim and Park 2017;Ozdemir, Çizel and Cizel 2012;Lee, Jeon and Kim 2011); motivation (Agyeiwaah et al. 2019;Almeida-Santana and Moreno-Gil 2018;Akgunduz and Cosar 2018;Antón, Camarero and Laguna-García 2017); destination image (Khasawneh and Alfandi 2019;Kim 2017;Chiu, Zeng and Cheng 2016;Zhang et al. 2014); perceived value (Kim, Holland and Han 2013;Sun, Geng-Qing and Xu 2013) and quality of experience (Suhartanto et al. 2019;Lee, Jeon and Kim 2011). Other antecedents of tourism loyalty have also been considered, albeit to a lesser extent. They include safety, novelty seeking, expectations, travel characteristics, price fairness or travellers’ characteristics (Vo 2019;Albaity and Melhem 2017;Tasci 2017;Wong, Wu and Cheng 2014;Kim, Holland and Han 2013;Prayag and Ryan 2012;McDowall 2010).

More recently, attention has been centred on aspects of the tourist experience, such as visitor engagement, cultural contact, perceived sustainability or perceived fairness. In his study of ecotourism in Korea,Kim (2017) found that memorable tourism experiences were the most influential determinant of behavioural intentions, the intention to revisit and WOM publicity. In the context of cultural tourism,Chen and Rahman (2018) found that visitor engagement significantly and positively influenced cultural contact and memorable tourism experiences. Urban tourism research conducted byLai, Hitchcock and Liu (2018) revealed that the tourist–resident relationship has significant effects on trip satisfaction. The analysis of two tourist destinations in Spain and Italy carried out byIniesta-Bonillo, Sánchez-Fernández and Jiménez-Castillo (2016) showed that visitors' perceived sustainability of a tourist destination was a determining factor of perceived value and satisfaction. Similarly, Brščić and Šugar (2020) found that the perceptions of beach comfort, beautiful scenery and beach cleanliness condition tourists’ satisfaction. Finally,Hwang, Baloglu and Tanford (2019) found that the perception of fairness significantly influences loyalty intention.

2.2. Perceived ethics of destination

Tourists’ experiences at their destination prove crucial in explaining their behaviour both during and after travel. Essentially, they affect their behaviour in three ways: economically, socio-culturally and environmentally (Gao, Huang and Zhang 2016).Weeden (2005) pointed out that addressing ethical aspects provides competitive advantages for businesses and by extension for the destinations themselves. This author goes even further, claiming that it is their perception of ethical considerations that leads tourists to behave responsibly in the destination (Weeden 2014). In this sense, the perceived ethics of the destination is of vital importance in the quest for more sustainable tourism.

Modern-day tourists are generally far more demanding than before. However, a new type of tourist has emerged that is more respectful and responsible towards the host environment and society. In this case, perceived economic, social and environmental issues contribute to determining a destination’s ethical image and reputation. For these tourists, self-fulfilment, knowledge and exploration are essential. There is also an ethical component that is more directly related to aspects such as personal growth and the quest for happiness (Barbieri, Santos and Katsube 2012).

Tourists’ perception of ethical aspects contributes to forging a destination’s image. Essentially this perception consists of an emotional and reasoned representation of a destination that stems from both the affective appraisals relating to an individual’s feelings towards the object and the perceptive/cognitive evaluations referring to the individual’s own knowledge of that object (Kanwel et al. 2019). Destination image can influence tourists’ behaviour to a considerable extent, both in terms of their choice of destination and behavioural intention (Khasawneh and Alfandi 2019;Zeugner-Roth and Žabkar 2015;Hosany and Prayag 2013). The perceived ethics of the destination will help to form cognitive evaluations and therefore determine tourists’ behaviour. The perception of the destination’s ethical component contributes to shaping expectations and therefore also the perceived quality. Ethical considerations will clearly affect the quality and added value of tourism products (Donyadide 2010).

The ethical aspects of travel are of increasing importance for tourists, and therefore will determine their perceptions.Ribeiro et al. (2017) claim that tourists’ interaction with others at the destination will determine emotional solidarity and condition satisfaction levels and the likelihood of revisits.Hwang, Baloglu and Tanford (2019) indicate that “the reviewed literature finds a direct link between perceptions of fairness and loyalty intentions in a variety of service settings”.

Despite the apparent relevance of ethical considerations on tourists’ behaviour, we are unable to find any studies that provide an integrated model for these aspects. Consequently, and in line with research into the determinants underlying tourists’ behaviour, our study hypothesizes that tourists’ satisfaction, perceived quality of the trip and destination loyalty depend on the level and nature of the perceived ethics of destination. Our first three hypotheses are given below:

H1: The more favourable the perceived ethical issues of destination, the higher overall satisfaction will be.

H2: The more favourable the ethical issues of destination, the higher the perceived quality of the trip will be.

H3: The higher perceived ethics of destination, the higher destination loyalty will be.

2.3. Perceived trip quality

In line with other research (Chen and Tsai 2007), for the purpose of our study perceived trip quality is understood as the tourists’ assessment of service quality in terms of food, accommodation, tourist attractions, transport and the local environment. Expectations play a key role in tourists’ behaviour (Dodds, Graci and Holmes 2010).Chen and Tsai (2007) consider that perceived trip quality is based on a comparison of expectations and actual performance. They also believe that trip quality is a representation of the destination experience. Various authors claim that satisfaction is positively conditioned by expectations, perceived quality and perceived value (Padlee et al. 2019;Eusébio and Vieira 2013).Moon and Han (2019) pointed out that perceived value is a stronger mediator between involvement and satisfaction than perceived price reasonableness.

It seems clear that loyalty is the result of a positive experience in the destination. In this regard, perceived quality has been recognised as an antecedent to tourism satisfaction and future intended behaviour (Babić-Hodović et al. 2019;Chen and Tsai 2007). Quality not only affects perceptions of value and satisfaction, but also has a direct influence on behavioural intention. According toPetrick (2004), quality has a direct and moderating effect, and some authors even go so far as to claim that perceived quality has a greater influence on behavioural intentions than actual tourist satisfaction (Baker and Crompton 2000).Kladou and Kehagias (2014) assert that “loyalty, as expressed by items such as recommendation and re-visitation, is mostly influenced by quality”.

Considering this background, the following hypotheses may be made:

H4: The higher perceived trip quality, the higher overall satisfaction will be.

H5: The higher perceived trip quality, the higher tourist loyalty will be.

2.4. Overall satisfaction

Consumer satisfaction is defined as a cognitive or emotional judgement based on an individual’s experience with a product or service (Akhoondnejad 2016). However, analysing satisfaction with a tourist destination is a more complex process than with individual service providers. Indeed, in addition to service quality, a number of other destination attributes will influence overall satisfaction (Kim and Brown 2012). Satisfaction with the tourist experience can be measured by the sense of enjoyment with the destination’s attributes or by overall judgements and feelings regarding the site experience. A number of authors define these two approaches to satisfaction as ‘attribute’ or ‘transaction- specific’ satisfaction and ‘overall’ satisfaction (Hall, O’Mahony and Gayler 2017;Prayag and Ryan 2012). Various studies have concluded that attribute satisfaction has a positive impact on overall satisfaction (Pérez Campdesuñer et al. 2017), whilst others consider that overall satisfaction is more than the mere sum of satisfaction with various separate attributes (Chi and Qu 2009). Furthermore, overall satisfaction would appear to be a more stable construct than transaction-specific satisfaction (Prayag and Ryan 2012). In line with other studies (Ramseook-Munhurruna, Seebalucka and Naidoo 2015), for the purpose of our research we consider overall satisfaction to be tourists’ general satisfaction with the travel experience.

Tourist satisfaction is important to successful destination marketing because it influences tourists’ behaviour. This is firstly due to the fact that satisfied tourists are more willing to pay more, and secondly because they will recommend the destination to others and probably return themselves (Deng and Pierskalla 2018). A large amount of research has been conducted into the antecedents and consequences of satisfaction (Sánchez-Rebull et al. 2018). Many authors conclude that overall tourist satisfaction is an antecedent to tourist loyalty (Padlee et al. 2019;Wu 2016;Chi and Qu 2008;Baker and Crompton 2000), mediates with image and is associated with attributes, expectations, consumer experience or perceived quality (Hu 2016;Wang et al. 2009;Chi and Qu 2008;Chen and Tsai 2007). This leads us to a final hypothesis:

H6: The higher the overall satisfaction, the higher destination loyalty will be.

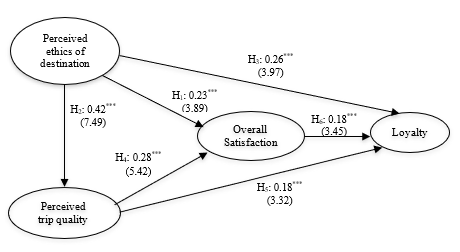

Figure 1 shows the conceptual model.

3. METHODOLOGY

We designed a questionnaire to verify the hypotheses of the proposed model. The survey instrument was revised and finalised, based on feedback from a pilot sample of 55 international tourists. The final questionnaire was conducted in English and Spanish and included two types of questions. On the one hand, a series of questions related to ethical aspects of the destination, image, perceived trip quality, satisfaction and loyalty. In this case, respondents were asked to indicate their agreement level for each item on a five-point Likert-type scale, from “strongly disagree (=1)” to “strongly agree (5)”. In addition, a series of questions related to the tourists’ profile were included, with the objective of ascertaining age, education level, occupation level, monthly income, travel party, length of stay and previous experience, among other aspects. In this case, a categorical scale was used.

Ethically-aware tourists demand reassurances that their travel experience does not impact negatively on the host society or environment. In this sense, ethical tourism must address its economic, social and environmental impact on the tourism industry, minimising the negative effects whilst at the same time acting as a vehicle for individual and collective fulfilment, as posited by the Global Code of Ethics for Tourism (UNWTO 2017). An ethical destination should encourage personal development through participation and contact with local communities. Emotional aspects such as wellbeing allow for the construction of an ethical image of a destination (Mcdonald 2015). Perceived destination ethics, representing economic, socio-cultural, environmental and wellbeing aspects, were measured using 13 items taken from expert opinion[1], a review of previous studies and a five-point Likert-type scale (Uysal et al. 2016;Su et al. 2015;Jamal and Camargo 2014;Kim, Holland and Han 2013). Perceived trip quality was measured with 5 formative indicators, in line with literature related to this construct (Chen and Tsai 2007). Overall satisfaction was measured by means of a single item, while loyalty was measured using 2 items (Prayag and Ryan 2012;Chi and Qu 2008;Chen and Tsai 2007).

The target population comprised international visitors to the city of Quito (Ecuador). The sample was selected using a stratified random sampling method based on tourists’ geographical origins. More than 80% came from North America, South America and Europe. The strata were made up of tourists over the age of 18 from these three regions. The number of tourists interviewed in each stratum was proportional to the number of tourist in the target population. Moreover, in order to ensure that the tourists had prior experience in the destination, they were required to have already completed at least 50% of their planned stay in the city. The empirical study was carried out during May and June 2016. The surveys were conducted in Quito’s most popular tourist areas and at Antonio José de Sucre International Airport. After screening the responses and discarding unusable questionnaires, 419 valid questionnaires were obtained. The sample size was in line with the level recommended in literature for structural equation models with similar complexity (So et al. 2014;Bagozzi and Yi 2012).

The respondent profile is summarised inTable 1. The tourists were mainly from the United States, Venezuela, Colombia and Spain. The vast majority of respondents were aged between 31 and 54 (54.9%), with a slightly higher number of male visitors (53.7%). The respondent profile is a person with university studies, visiting the city for fewer than 5 days and accompanied by friends or relatives. Differences were observed according to the region of origin. South American tourists stayed in the city for an average of 7.6 days, North Americans for 4.5 days and Europeans for 4.4 days.

Quito was the main travel destination of just 37.5% of respondents. Additional destinations included the Galapagos (16%), Otavalo (14%), Guayaquil (14%) and Latacunga (10%). The majority were first-time visitors to the city that had used online resources to learn about its attractions and amenities.

The data were analysed in two stages. Firstly, exploratory factor analyses on ethical issues affecting the destination were conducted using a principal component method with varimax rotation in order to examine dimensionalities and psychometric properties. Secondly, the relationship between the perceived ethics of destination, perceived trip quality, overall satisfaction and loyalty were tested empirically using the structural equation modelling (SEM) technique with AMOS in a second phase.

4 EMPIRICAL RESULTS

As discussed above, the perception of ethical aspects of the destination was measured using a multi-attribute approach. The principal component factor analysis was applied to the final data in order to scrutinise the underlying dimensions of the perceived ethics of destination. Three factors with an eigenvalue greater than one explained 58% of the variance of the ethical perception on the destination scale. Two items with factor loadings of less than 0.5 were removed from the scale. The varimax-rotated factor pattern indicates that the first factor concerns the “wellbeing of the local people” (5 items, a=0.76). The second factor relates to “subjective wellbeing” (3 items, a=0.74) and the third factor consists of “active participation and equality” (3 items, 0.58). Next, the arithmetic means of items included within the three factors was used to build the construct perceived ethics for subsequent analysis.Table 2 summarises the results of the factor analysis.

Perceived trip quality, overall satisfaction and loyalty are presented inTable 3. The mean values for perceived quality ranged from 3.62 to 4.12, which also seems to indicate a high perceived quality of the trip. The existence of multicollinearity was tested (Diamantopoulos and Winklhofer 2001). The highest value of the variance inflation factor (VIF) stood at a relatively low 1.606, (Henseler, Ringle and Sinkovics 2009). In addition, tolerance values were close to 1. The Condition Index (CI) was below 30. Therefore, multicollinearity was not considered a problem in this study. The means for overall satisfaction scale ranged from 4.40 to 4.51, indicating a high degree of satisfaction amongst tourists travelling to Ecuador in general, and Quito in particular. In turn, the means of loyalty scale ranged from 3.57 to 4.36, indicating that they were more likely to recommend Quito to others than actually revisit the city. The constructs were considered reliable (alpha value= 0.851).

Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) was used to test the proposed conceptual model inFigure1. SPSS software was used to check missing values and outliers. The results showed that the data have no significant outliers. The listwise deletion method was used as the number of missing values was lower than 10%. Normality was checked with SPSS and AMOS. Skew was < 3 and kurtosis < 10, which suggests a normal distribution of the variables observed (Hair et al. 2010). A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted using AMOS software with maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) to test the convergent validity of the constructs used in the subsequent analysis. AsTable 4 shows, the convergent validity of CFA results should be supported by item reliability, construct reliability and average variance extracted (AVE) (Hair et al. 1998). T-values for all the standardised factor loadings of the items were found to be significant (p<0.001). Construct reliability estimates ranging from 0.75 to 0.87 exceeded the recommended critical value of 0.7, indicating that it was satisfactory (Hair et al. 1998). The AVE for all constructs exceeded the minimum value of 0.50, suggesting good convergent validity (Hair et al. 1998;Fornell and Larcker 1981). The Fornell-Larcker criterion shows that the square root of each AVE (0.71 for perceived ethics of destination and 0.87 for loyalty) is greater than the related inter-construct correlations (0.40), indicating adequate discriminant validity. Consequently, all these assessments support the soundness of the measurement model.

FL: factor loadings; SE: standard error; SFL: standardized factor loading; CR: construct reliability; AVE: average variance extracted.

The proposed model was tested using the four constructs; namely, perceived ethics of destination, perceived trip quality, overall satisfaction and destination loyalty. The “wellbeing of the local people”, “subjective wellbeing” and “active participation and equity” were used as measurement variables for the perceived ethics of destination. Composite scores for perceived trip quality were obtained from the mean scores across items representing that construct. In addition, satisfaction and loyalty were measured with one and two items respectively, as stated above. SEM analysis was conducted to examine the relationship between the five constructs.

The model proposed inFigure1 was compared with a series of alternative competing models. More specifically, the model was compared with three alternative models. A model (A) that did not include the path between “perceived ethics of destination” and “destination loyalty”; a model (B) that did not include the path between “perceived trip quality” and “destination loyalty”; and finally, a model (C) that did not include the path between “perceived ethics of destination” and “destination loyalty” or the path between “perceived trip quality” and “destination loyalty”.

The fit of the structural models was examined using maximum likelihood estimation. The fit indices of the model comparison are summarised inTable 5 . Following the recommendations of Jöreskog and Sorbom (1995), sequential Chi-square (c2) tests were performed to assess the differences in estimated construct co-variances explained by the four models. The results of the c2 difference tests favoured the proposed theoretical model. A series of goodness-of-fit measures was also compared, indicating that the proposed theoretical model achieved the best level of model fit. The results indicate c2 is 12.91 with 10 degrees of freedom (d.f.) and p= 0.22, greater than 0.05 and therefore statistically insignificant. The c2/ d.f. ratio of the model is 1.29 (12.91/ 10), indicating an acceptable fit. Other indicators of goodness of fit are GFI= 0.99, AGFI= 0.97, NFI= 0.98, CFI= 0.99, RMSEA= 0.03 and RMR= 0.01. The results indicated that the data collected are consistent with the hypothesised model.

Due to the nature of the study, tests were conducted for common method bias, specifically because the five-point Likert scale is prone to capturing response sets. Two tests were also used to determine the degree of variance in the common method bias. The Harman one-factor test (Podsakoff and Organ 1986) revealed that no single general factor accounted for the majority variance in an exploratory factor analytic. In the model, single factor variance stood at 32.6%, indicating no common method bias. On the other hand, based on (Podsakoff et al. 2003), a new model with all the observed variables loaded onto one factor was re-estimated, producing unacceptable results (Chi-square=304.111; df=14; GFI=0.79; RMSEA=3.204). Overall, these results suggest that common method variance is not a pervasive issue in the data.

| Theoretical | Model A | Model B | Model C | |

| X2 | 12.91 | 28.86 | 23.67 | 55.72 |

| d.f | 10 | 11 | 11 | 12 |

| GFI | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.96 |

| AGFI | 0.97 | 0.95 | 0.96 | 0.92 |

| NFI | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.94 |

| CFI | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.95 |

| RMSEA | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.09 |

| RMR | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.08 |

Figure 2 presents the results of SEM analysis. The results of hypothesis testing indicated that all the paths had significant path coefficients. As Fig. 2 shows, H1 prediction was supported (t= 3.89, p< 0.01), confirming that perceived ethics of destination have a significantly positive effect on overall satisfaction. Our findings indicated that perceived ethics of destination have a positive influence on perceived trip quality (t= 7.49, p< 0.01), supporting H2. Perceived trip quality also has positive effects on overall satisfaction (t=5.42, p<0.01), supporting H4. Overall satisfaction, as hypothesised, has a significantly positive effect on loyalty (t= 3.45, p< 0.01), supporting H6. H3 and H5 were supported, showing that perceived ethics of destination and trip quality have a significantly positive effect on loyalty (t= 3.97, p< 0.01 and t= 3.32, p< 0.01 respectively).

Table 6 summarises the results of the hypothesis testing. Perceived ethics of destination directly and indirectly influence overall satisfaction. Likewise, perceived ethics of destination also have a direct and indirect influence on loyalty. Finally, overall satisfaction partially mediated the relationship between perceived trip quality and destination loyalty.

Table 7 illustrates the direct and indirect effects. The greatest total effect of the perceived ethics of destination occurs above perceived trip quality, which stood at 0.424. Similarly, the total effect of perceived ethics of destination on overall satisfaction was found to be 0.347: 0.230 directly and 0.117 indirectly. The total effect of perceived ethics of destination on loyalty was found to be 0.398. This indicates that perceived ethics of destination is the most important variable that influences tourist loyalty.

5 DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

In an increasingly competitive scenario, loyalty has emerged as a strategic goal for cities. Considered for the purpose of our study as the intention to recommend and/or revisit a destination, is also a strong indicator of a destination’s success, as it reflects tourists’ degree of satisfaction. Understanding the determinants of tourist loyalty is therefore crucial for destination managers, as it enables them to prioritise those elements capable of boosting loyalty. Numerous studies have addressed the question of loyalty and its determinants, and the most frequently cited antecedents in this sense include satisfaction, destination image, perceived quality and motivation.

More recently, attention has been focused on tourists’ perception of certain aspects of a destination, such as sustainability, tourist-resident relationships and perceived fairness (Chen and Rahman 2018). Although several studies appear to implicitly accept the importance of ethical considerations on tourists’ behaviour, none address this question in an explicit manner. This study fills this research gap by conducting an empirical study and including the perceived ethics of destination in tourists’ behaviour. More specifically, it has tested the effects of perceived ethics of destination, perceived trip quality and overall satisfaction on loyalty. It also tested the relationships among predictors. The structural relationships between all variables in the study were tested using data obtained from 419 international tourists visiting Quito in Ecuador and applying structural equation modelling (SEM).

The findings showed that perceived ethics of destination appear to be the principal influence on behavioural intentions, namely the intention to revisit and willingness to recommend. The perceived ethical issues of destination have both a direct and indirect influence on behavioural intentions. Moreover, perceived ethics of destination have an important effect on trip quality and overall satisfaction. It seems that tourists who perceived aspects of the destination as ethical were more likely to perceive the destination as being of high quality, which in turn would strengthen their degree of satisfaction and consequent loyalty. The results also showed that perceived quality influenced overall satisfaction and loyalty. These findings confirms the findings of previous research (Vo and Chovancová 2019;Hallak, Assaker and El-Haddad 2017;Wang, Tran and Tran 2017). It seems that international tourists who perceived high quality were more likely to be satisfied and therefore more loyal to the destination. Finally, in line with many other research projects, overall satisfaction influenced loyalty (Antón, Camarero and Laguna-García 2017;Kim and Park 2017). In other words, tourists’ satisfaction with their visit to Quito would influence their loyalty to the city.

The study has major theoretical and managerial implications. In terms of the former, our research was conducted in South America, a region that has received little attention in terms of the analysis of tourists’ behaviour based on integrated models. Our work also contributes to literature by including for the first time the perception of destination ethics as a predictor for loyalty. Finally, our research considered the relationships between predictors. Although the connection between the perceived quality and overall satisfaction with the travel experience has been addressed in tourism literature, the role of the perceived ethics of destination had not been considered.

The findings also have a series of managerial implications. On the one hand, they suggest that perceived ethics of destination is a significant predictor of tourist loyalty. Therefore, any decision to improve these aspects, such as providing more authentic tourist experiences, will contribute to destination loyalty. Loyal tourists will revisit the destination and/or recommend it to third parties by WOM, thereby providing an efficient and inexpensive means of promotion. In recent years, competition to attract tourists has become increasingly fierce. Although producers have to offer a specific product in a specific place, with the consequent spatial immobility, demand has become increasingly mobile, allowing for the global consumption of tourist services. In this context, a destination’s success does not depend only on economic factors but is also conditioned by cultural changes that influence tourists’ expectations. Tourists are demanding experiences of increasingly higher standards, forcing the industry and destination managers to create differentiated products that satisfy their expectations and needs.

Destinations should increase trip quality in order to boost tourist´s satisfaction and loyalty. In the specific case of Quito, improvements could be made particularly with regard to the attractions, accessibility and transport, which scored lowest among tourists. Increasing the supply or leisure and entertainment activities and more efficient means of transport would prove effective in improving quality. In turn, this would boost overall satisfaction with the travel experience, as the findings showed that perceived trip quality weighed most heavily in defining overall satisfaction.

Finally, as with all research, our work has a series of limitations that could be addressed in future research. Firstly, our study is limited to a single city and country. Secondly, it considers international tourists only. Research should therefore be conducted in other cities and countries, and also include domestic tourists. Thirdly, and asWeeden (2014) andLee et al. (2017) explained, the perception of ethical considerations leads tourists to behave responsibly in the destination. Future studies could therefore analyse how this perception affects the degree of responsibility shown by tourists. Finally, in line with studies such as those byMoeller, Dolnicar and Leisch (2011) andNickerson, Jorgenson and Boley (2016), who demonstrated that destination expenditure is higher among sustainable tourists, our study has shown a similar trend amongst tourists with more sensitive, ethical or responsible motivations, thereby increasing the positive economic impact, a consideration that will be addressed in-depth in future research.

REFERENCES

Agyeiwaah E.; Otoo F.E.; Suntikul W.; Huang W-J. (2019), "Understanding culinary tourist motivation, experience, satisfaction, and loyalty using a structural approach",Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing, Vol. 36, No. 3, pp. 295-313. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2018.1541775

Akgunduz Y.; Cosar Y. (2018), "Motivations of event tourism participants and behavioural intentions", Tourism and Hospitality Management, Vol. 24, No. 2, pp. 341-358. https://doi.org/10.20867/thm.24.2.4

Akhoondnejad A. (2016), "Tourist loyalty to a local cultural event: The case of Turkmen handicrafts festival", Tourism Management, Vol. 52, pp. 468-477. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2015.06.027

Albaity M.; Melhem S.B. (2017), "Novelty seeking, image, and loyalty – The mediating role of satisfaction and moderating role of length of stay: International tourists' perspective", Tourism Management Perspectives, Vol. 23, No. 30, pp. 37 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2017.04.001

Almeida-Santana A.; Moreno-Gil S. (2018), "Understanding tourism loyalty: Horizontal vs. destination loyalty", Tourism Management, Vol. 65, pp. 245-255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2017.10.011

Antón C.; Camarero C.; Laguna-García M. (2017), "Towards a new approach of destination loyalty drivers: satisfaction, visit intensity and tourist motivations", Current Issues in Tourism, Vol. 20, No. 3, pp. 238-260. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2014.936834

Babić-Hodović V.; Arslanagić-Kalajdžić M.; B a (2019), "Ipa and Servperf quality conceptualisations and their tole for satisfaction with hotel services", Tourism and hospitality management, Vol. 25, No. 1, pp. 1-17. https://doi.org/10.20867/thm.25.1.4

Bagozzi R.P.; Yi (2012), "Specification, Evaluation, and Interpretation of Structural Equation Models", Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, Vol. 40, No. 1, pp. 8-34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-011-0278-x

Baker D.; Crompton J. (2000), "Quality, satisfaction and behavioral intentions", Annals of Tourism Research, Vol. 27, No. 3, pp. 785-804. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(99)00108-5

Barbieri C.; Santos C.; Katsube Y. (2012), "Volunteer tourism: On-the-ground observations from Rwanda", Tourism Management, Vol. 33, No. 3, pp. 509-516. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2011.05.009

Brščić K.; Šugar T. (2020), "Users’ perceptions and satisfaction as indicators for sustainable beach management", Tourism and hospitality management, Vol. 26, No. 1, pp. 33-48. https://doi.org/10.20867/thm.26.1.3

Chen C-F.; Tsai D. (2007), "How destination image and evaluative factors affect behavioural intentions?", Tourism Management, Vol. 28, pp. 1115-1122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2006.07.007

Chen H.; Rahman I. (2018), "Cultural tourism: An analysis of engagement, cultural contact, memorable tourism experience and destination loyalty", Tourism Management Perspectives, Vol. 26, pp. 153-163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2017.10.006

Chi C.G-Q.; Qu H. (2008), "Examining the structural relationships of destination image, tourist satisfaction and destination loyalty: An integrated approach", Tourism Management, Vol. 29, pp. 624-636. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2007.06.007

Chi C.G-Q.; Qu H. (2009), "Examining the Relationship Between Tourists’ Attribute Satisfaction and Overall Satisfaction", Journal of Hospitality Marketing and management, Vol. 18, No. 1, pp. 4-25. https://doi.org/ 10.1080/19368620801988891

Chiu W.; Zeng S.; Cheng P.S-T. (2016), "The influence of destination image and tourist satisfaction on tourist loyalty: a case study of Chinese tourists in Korea", International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, Vol. 10, No. 2, pp. 223-234. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCTHR-07-2015-0080

Deng J.; Pierskalla C.D. (2018), "inking Importance–Performance Analysis, Satisfaction, and Loyalty: A Study of Savannah", Sustainability, Vol. 10, No. 3, pp. 704. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10030704

Diamantopoulos D.; Winklhofer H. (2001), "Index Construction with Formative Indicators: An Alternative to Scale Development", Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 38, No. 2, pp. 269-277. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkr.38.2.269.18845

Dodds R.; Graci S.; Holmes M. (2010), "Does the tourist care? A comparison of tourists in Koh Phi, Thailand and Gili Trawangan, Indonesia", Journal of Sustainable Tourism, Vol. 18, No. 2, pp. 207-222. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09669580903215162

Eusébio C.; Vieira A.L. (2013), "Destination Attributes' Evaluation, Satisfaction and Behavioural Intentions: a Structural Modelling Approach", International Journal of Tourism Research, Vol. 15, No. 1, pp. 66-80. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.877

Fan Z.; Zhong S.; Zhang W. (2012), "Harmonious Tourism Environment and Tourists Perception: An Empirical Study of Mountain-Type World Cultural Heritage Sites in China", Journal of Service Science and Management, Vol. 5, No. 1, pp. 95-100. https://doi.org/10.4236/jssm.2012.51012

Fornell C.; Larcker D.F. (1981), "Evaluating structural equations models with unobservable variables and measurement error", Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 18, No. 1, pp. 39-50. https://doi.org/10.2307/3151312

Gao J.; Huang Z.; Zhang C. (2016), "Tourist’ perceptions of responsibility: An application of norm-activation theory", Journal of Sustainable Tourism, pp. 276-291. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2016.1202954

Hall J.; O´Mahony B.; Gayler J. (2017), "Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing", Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing, Vol. 34, No. 6, pp. 764. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2016.1232672

Hallak R.; Assaker G.; El-Haddad R. (2017), "Re-examining the relationships among perceived quality, value, satisfaction, and destination loyalty: A higher-order structural model", Journal of Vacation Marketing, Vol. 24, No. 2, pp. 118-135. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1356766717690572

Hapsari R. (2018), "Creating educational theme park visitor loyalty: the role of experience-based satisfaction, image and value", Tourism and hospitality management, Vol. 24, No. 2, pp. 359-274. https://doi.org/10.20867/thm.24.2.7

Henseler J.; Ringle C.M.; Sinkovics R.R. (2009), "The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing", in Sinkovics, R.R. and Ghauri, P.N. (Eds.) Advances in International Marketing, Bingley, pp. 277-319. https://doi.org/10.1108/s1474-7979(2009)0000020014

Hosany S.; Prayag G. (2013), "Patterns of tourists' emotional responses, satisfaction, and intention to recommend", Journal of Business Research, Vol. 66, No. 6, pp. 730-737. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.09.011

Hu C.W. (2016), "Destination loyalty modeling of the global tourism", Journal of Business Research, Vol. 69, pp. 2213-2219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.12.032

Hwang E.; Baloglu S.; Tanford S. (2019), "Building loyalty through reward programs: The influence of perceptions of fairness and brand attachment", International Journal of Hospitality Management, Vol. 76, pp. 19-28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2018.03.009

Iniesta-Bonillo M.A.; Sánchez-Fernández R.; Jiménez-Castillo D. (2016), "Sustainability, value, and satisfaction: Model testing and cross-validation in tourist destinations", Journal of Business Research, Vol. 69, No. 11, pp. 5002-5007. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.04.071

Jamal T.; Camargo B.A. (2014), "Sustainable tourism, justice and an ethic of care: Toward the just destination", Journal of Sustainable Tourism, Vol. 22, No. 1, pp. 11-30. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2013.786084

Kanwel S.; Lingqiang Z.; Asif M.; Hwang J.; Hussain A.; Jameel A. (2019), "The Influence of Destination Image on Tourist Loyalty and Intention to Visit: Testing a Multiple Mediation Approach", Sustainability, Vol. 11, No. 22, pp. 6401 https://doi.org/10.3390/su11226401

Khasawneh M.S.; Alfandi A.M. (2019), "Determining behaviour intentions from the overall destination image and risk perception", Tourism and Hospitality Management, Vol. 25, No. 2, pp. 355-375. https://doi.org/10.20867/thm.25.2.6

Kim A.K.; Brown G. (2012), "Understanding the relationships between perceived travel experiences, overall satisfaction, and destination loyalty", Anatolia – An International Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Research, Vol. 23, No. 3, pp. 328-347. https://doi.org/10.1080/13032917.2012.696272

Kim S-H.; Holl ; S. Han (2013), "A Structural Model for Examining how Destination Image, Perceived Value, and Service Quality Affect Destination Loyalty: a Case Study of Orlando", International Journal of Tourism Research, Vol. 15, No. 4, pp. 313-328. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.1877

Kim K-H.; Park D-B. (2017), "Relationships Among Perceived Value, Satisfaction, and Loyalty: Community-Based Ecotourism in Korea", Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing, Vol. 34, No. 2, pp. 171-191. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2016.1156609

Kim J-H. (2017), "The Impact of Memorable Tourism Experiences on Loyalty Behaviors: The Mediating Effects of Destination Image and Satisfaction", Journal of Travel Research, Vol. 57, No. 7, pp. 856-870. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0047287517721369

Kladou S.; Kehagias J. (2014), "Assessing destination brand equity: An integrated approach", Journal of Destination Marketing and Management, Vol. 3, pp. 2-10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2013.11.002

Lai I.K.W.; Hitchcock M.; Lu D.; Liu Y. (2018), "The Influence of Word of Mouth on Tourism Destination Choice: Tourist–Resident Relationship and Safety Perception among Mainland Chinese Tourists Visiting Macau", Sustainability, Vol. 10, No. 7, pp. 2114. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10072114

Lee S.; Jeon S.; Kim D. (2011), "The impact of tour quality and tourist satisfaction on tourist loyalty: The case of Chinese tourists in Korea", Tourism Management, Vol. 23, No. 5, pp. 1115-1124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2010.09.016

Lee H.Y.; Bonn M.A.; Reid E.L.; Kim W.G. (2017), "Differences in tourist ethical judgment and responsible tourism intention: An ethical scenario approach", Tourism Management, Vol. 60, pp. 298-307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2016.12.003

McDowall S. (2010), "International Tourist Satisfaction and Destination Loyalty: Bangkok, Thailand", Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, Vol. 15, No. 1, pp. 21-42. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941660903510040

Moeller T.; Dolnicar S.; Leisch F. (2011), "The sustainability–profitability trade-off in tourism: can it be overcome?", Journal of Sustainable Tourism, Vol. 19, No. 2, pp. 155-169. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11195279

Moliner M.Á.; Monferrer D.; Estrada M.; Rodríguez R.M. (2019), "Environmental Sustainability and the Hospitality Customer Experience: A Study in Tourist Accommodation", Sustainability, Vol. 11, No. 19, pp. 5279. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11195279

Moon H.G.; Han H. (2019), "Tourist experience quality and loyalty to an island destination: the moderating impact of destination image", Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing, Vol. 36, No. 1, pp. 43-59. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2018.1494083

Nickerson N.P.; Jorgenson J.; Boley B.B. (2016), "Are sustainable tourists a higher spending market?", Tourism Management, Vol. 54, pp. 170-177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2015.11.009

Ozdemir B.; Çizel B.; Cizel R.B. (2012), "Satisfaction With All-Inclusive Tourism Resorts: The Effects of Satisfaction With Destination and Destination Loyalty", International Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Administration, Vol. 13, No. 2, pp. 109-130. https://doi.org/10.1080/15256480.2012.669313

Padlee S.F.; Thaw C.Y.; Zulkiffi S.N.A. (2019), "The relationship between service quality, customer satisfaction and behavioural intentions in the hospitality industry", Tourism and Hospitality Management, Vol. 25, No. 1, pp. 121-140. https://doi.org/10.20867/thm.25.1.9

Pérez Campdesuñer R.; García Vidal G.; Sánchez Rodríguez A.; Martínez Vivar R. (2017), "Structural equation model: influence on tourist satisfaction with destination attributes", Tourism and hospitality management, Vol. 23, No. 2, pp. 219-233. https://doi.org/10.20867/thm.23.2.2

Petrick J.F. (2004), "The Roles of Quality, Value, and Satisfaction in Predicting Cruise Passengers’ Behavioral Intentions", Journal of Travel Research, Vol. 42, No. 4, pp. 397-407. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287504263037

Podsakoff P.M.; Organ D.W. (1986), "Self-Reports in Organizational Research: Problems and Prospects", Journal of Management, Vol. 12, No. 4, pp. 531-544. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920638601200408

Podsakoff P.M.; MacKenzie S.B.; Lee J-Y.; Podsakoff N.P. (2003), "PCommon Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies", Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 88, No. 5, pp. 879-903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

Prayag G.; Ryan C. (2012), "Antecedents of Tourists’ Loyalty to Mauritius: The Role and Influence of Destination Image, Place Attachment, Personal Involvement, and Satisfaction", Journal of Travel Research, Vol. 51, No. 3, pp. 342-356. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287511410321

Ramseook-Munhurrun P.; Seebaluck V.N.; Naidoo P. (2015), "Examining the structural relationships of destination image, perceived value, tourist satisfaction and loyalty: case of Mauritius", Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 175, pp. 252-259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.01.1198

Ribeiro M.A.; Woosnam K.M.; Pinto P.; Silva J.A. (2017), "Tourists destination loyalty through emotional solidarity with residents: an integrative moderated mediation model", Journal of Travel Research, Vol. 57, No. 1, pp. 1-17. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287517699089

Sánchez-Rebull M-V.; Rudchenko V.; Martín J-C. (2018), "The antecedents and consequences of customer satisfaction in tourism: a systematic literature review", Tourism and hospitality management, Vol. 24, No. 1, pp. 151-183. https://doi.org/10.20867/thm.24.1.3

So K.K.F.; King C.; Sparks B.A, Wang (2014), "The Role of Customer Engagement in Building Consumer Loyalty to Tourism Brands", Journal of Travel Research, Vol. 55, No. 1, pp. 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287514541008

Suhartanto D.; Brien A.; Primiana I.; Wibisono N.; Triyuni N.N. (2019), "Tourist loyalty in creative tourism: the role of experience quality, value, satisfaction, and motivation", Current Issues in Tourism, Vol. 23, No. 27, pp. 867-879. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2019.1568400

Sun X.; Geng-Qing C.; Xu H. (2013), "Developing destination loyalty: the case of Hainan Island", Annals of Tourism Research, Vol. 43, pp. 547-577. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2013.04.006

Tasci A.D.A. (2017), "A quest for destination loyalty by profiling loyal travellers", Journal of Destination Marketing and Management, Vol. 6, pp. 207-220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2016.04.001

UNWTO (2017), Global Code of Ethics for Tourism. Ethics and Social Responsibility, viewed12 November 2019 , https://www.unwto.org/global-code-of-ethics-for-tourism

Uysal M.; Sirgy M.J.; Woo E.; Kim H.L. (2016), "Quality of life (QOL) and well-being research in tourism", Tourism Management, Vol. 53, pp. 244-261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2015.07.013

Vo N.T.; Chovancová M. (2019), "Customer satisfaction and engagement behaviors towards the room rate strategy of luxury hotels", Tourism and Hospitality Management, Vol. 25, No. 2, pp. 403-420. https://doi.org/10.20867/thm.25.2.7

Wang X.; Zhang J.; Gu C.; Zhen F. (2009), "Examining Antecedents and Consequences of Tourist Satisfaction: A Structural Modeling Approach", Tsinghua Science and Technology, Vol. 14, No. 3, pp. 397-406. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1007-0214(09)70057-4

Wang T.; Tran P.; Tran V. (2017), "Destination perceived quality, tourist satisfaction and word-of-mouth",Tourism Review, Vol. 72, No. 4, pp. 392-410. https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-06-2017-0103

Weeden C. (2005), "Ethical Tourism, Is its future in niche tourism?",Oxford https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-7506-6133-1.50030-5

Weeden C. (2014), "Responsible tourist behaviour",Oxford https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-7506-6133-1.50030-5

Wong J.; Wu H-C.; Cheng C-C. (2014), "An Empirical Analysis of Synthesizing the Effects of Festival Quality, Emotion, Festival Image and Festival Satisfaction on Festival Loyalty: A Case Study of Macau Food Festival",International Journal of Tourism Research, Vol. 17, No. 6, pp. 521-536. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2011

Wu C-W. (2016), "Destination loyalty modeling of the global tourism",Journal of Business Research , Vol. 69, pp. 2213-2219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.12.032

Yoon Y.; Uysal M. (2005), "An examination of the effects of motivation and satisfaction on destination loyalty: a structural model",Tourism management, Vol. 26, No. 1, pp. 45-56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2003.08.016

Zeugner-Roth K.P.; Žabkar V. (2015), "Bridging the gap between country and destination image: Assessing common facets and their predictive validity",Journal of Business Research , Vol. 68, No. 9, pp. 1844-1853. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.01.012

Zhang H.; Fu X.; Cai L.A.; Lu L. (2014), "Destination image and tourist loyalty: A meta-analysis",Tourism Management , Vol. 40, pp. 213-223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2013.06.006