Konzervatorsko-restauratorski proces orijentalnog rukopisa Aṭ-Ṭāriqa al-Muḥammadiyya

Conservation-restoration treatment of oriental manuscripts Aṭ-Ṭāriqa al-Muḥammadiyya

Nejra Ljubuškić

Nacionalna i Univerzitetska Biblioteka Bosne i Hercegovine, Sarajevo, Bosna i Hercegovina / National and University Library of B&H, Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina

nejra.ljubuskic@nub.ba

Primljeno / Received 18. 9. 2023.

Prihvaćeno / Accepted 9. 10. 2023.

Dostupan online / Available online: 10. 12. 2023.

Ključne riječi / Keywords

konzervacija, restauracija, uvez, rukopisi, orijentalni rukopisi, Aṭ-Ṭāriqa al-Muḥammadiyya, Mesudija, Birgivi

conservation, restoration, binding, manuscripts, oriental manuscripts, Aṭ-Ṭāriqa al-Muḥammadiyya, Mesudija, Birgivî

Sažetak / Abstract

Rad predstavlja konzervatorsko-restauratorski postupak orijentalnog rukopisa na turskom jeziku, Aṭ-Ṭāriqa al-Muḥammadiyya. Rukopis je skladišten u biblioteci tekije Mesudija1 koja posjeduje vrlo važnu staru i rijetku knjižnu građu među kojima posebno mjesto zauzimaju orijentalni rukopisi. Cilj restauracije je bio vraćanje funkcionalnosti uveza i očuvanja tekstova. Restauratorski tretmani su podrazumijevali: čišćenje listova mehaničkim i hemijskim putem, nadogradnju dijelova koji nedostaju japanskim papirom, ušivanje formi u knjižni blok, vez kapitalne trake te restauraciju izvornih korica. Izrađena je i konzervatorsko-restauratorska dokumentacija sa prijedlogom o rukovanju i preventivnoj konzervaciji rukopisa.

This paper represents the conservation-restoration process of the oriental manuscript in the Turkish language, Aṭ-Ṭāriqa al-Muḥammadiyya. The manuscript is stored in the library of the Tekke Mesudija2 which has very important old and rare book materials, among which oriental manuscripts hold a special place. The goal of the restoration was to restore the functionality of the binding and preserve the texts. The restoration treatments included: mechanical and chemical cleaning of the pages, repairing a missing portion of a page with Japanese paper, sewing the forms into the bookblock, embroidering the endband, and restoring the original covers. Conservation-restoration documentation with a proposal on the handling and preventive conservation of manuscripts was also prepared.

Uvod

Sarajevo je pod vlašću Osmanskog carstva bilo jedno od najvećih kulturnih centara Evrope sa vrlo bogatim kulturnim i umjetničkim životom. Pored velikog broja osnovnih škola i medresa, postojale su biblioteke, koje su bile, kao i danas, kako riznice znanja, tako i čuvari kulturnog naslijeđa i historije. Knjiga je u Osmanskom carstvu igrala vrlo bitnu ulogu u prenošenju znanja i umjetničkog izražavanja, ali je također bila izrazit ukrasni predmet. Rukopisi su u potpunosti bili rijetki i skupocjeni artefakti kojima se pridavala posebna pažnja pri izradi, pisanju ili prepisivanju sve do očuvanja i deponovanja. Tehnika uveza se stoljećima razvijala, pa se od pisanja na papirusu napredovalo do vrhunske izrade kožnih korica, čemu svjedoče rukopisi skladišteni u bibliotekama, muzejima i privatnim kolekcijama širom Bosne i Hercegovine. Orijentalni rukopis Aṭ-Ṭāriqa al-Muḥammadiyya, prepisan 1181/1760. godine, dio je fonda biblioteke Mesudija u Kaćunima koja sadrži preko 10.000 vrlo rijetkih i vrijednih djela. Puni naziv rukopisa glasi Eṭ-Ṭarîḳatü’l-Muḥammediyye ve’s-sîretü’l-Aḥmediyye’,3 a izvorni tekst potiče iz 16. stoljeća. Napisao ga je čuveni učenjak Muhammad b. Pir 'Ali al-Birgiwi ar-Rumi Taqiyyuddin4 (929/1573) te predstavlja jedno od najčitanijih tesavvufskih djela koje govori o lijepom ponašanju i principima vjerskog života u skladu sa sunnetom poslanika Muhammeda a.s. i Kur’ana kao Svete knjige u islamu. Djelo ima značajnu socijalnu i historijsku vrijednost, a napisano je običnim, čitljivim, narodnim jezikom. Tekst rukopisa se sastoji od tri glavna dijela, od kojih svaki ima tri poglavlja, te je napisan u obliku pitanja sa odgovorima (İslâm Ansiklopedisi, 2013). Prije same restauracije izvršena je detaljna fotodokumentacija i evidencija djela.

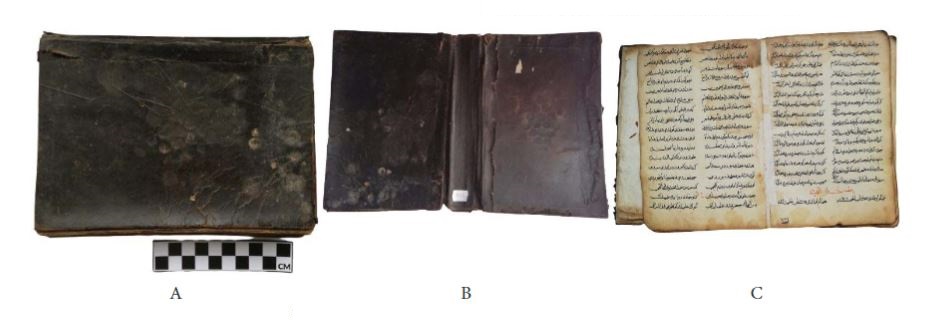

Opis stanja knjižnog bloka i uveza prije konzervatorskog postupka

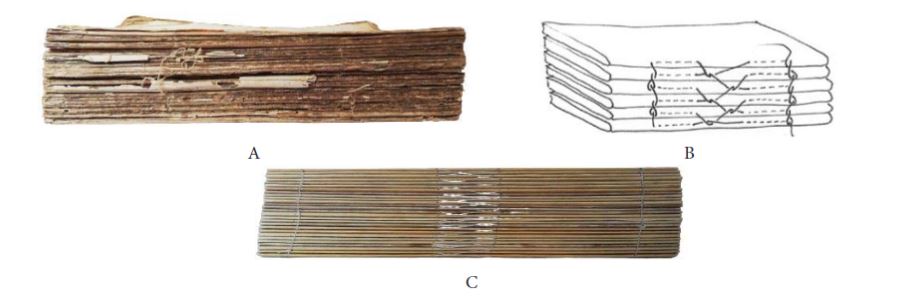

Knjižni blok se sastoji od 270 listova, uvezanih u 27 formi po 10 listova. Papir je prethodno repariran lijepljenjem samoljepljivih bijelih traka na original. Na mnogim listovima su primjetni produkti insekata, dok su unutar formi pronađeni ostaci insekata. Na stranicama tuš je razmazan izvan margina i preko teksta. Papir je prije ispisa teksta impregniran, što se primijeti po izrazitom sjaju listova. Zbog loših uvjeta skladištenja i djelovanja vlage, papir je u početnom stanju degradacije. Dekoracija prisutna na koricama je izvedena kao slijepi (reljefni) tisak. Klasičnim kožnim koricama islamskog knjigovestva nedostaju preklop i klapna, te su zbog prethodne restauracije oštećene i ne odgovaraju knjižnom bloku. Forzec (predlist i zalist), čija je osnovna uloga povezivanje korica sa knjižnim blokom, potpuno nedostaje. Na hrptu na kojem je ostao zalijepljen organtin vidljivi su konci gdje je ušivena dvostruka kapitalna traka koja je oštećena. Na unutrašnjoj strani korica ispisana su dva reda teksta. Tekst je na turskom jeziku arapskim pismom (nesih), pisan dvjema vrstama tinte, crnom i crvenom. Tuš je osjetljiv na vodu, što je primjetno po razmazanim dijelovima margina i teksta.

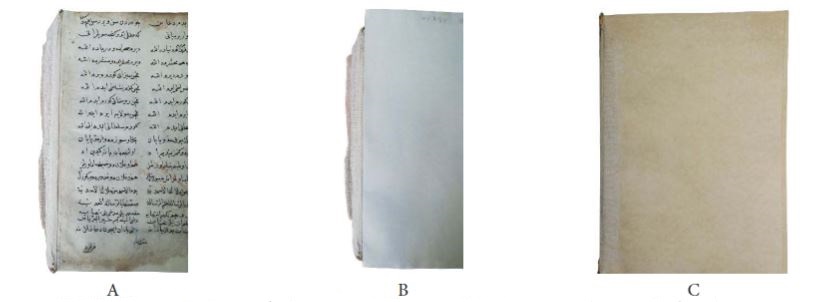

Slika 1. A), B) i C) Izgled rukopisa prije restauracije

Konzervatorsko-restauratorski postupak na knjižnom bloku

Čišćenje knjižnog bloka

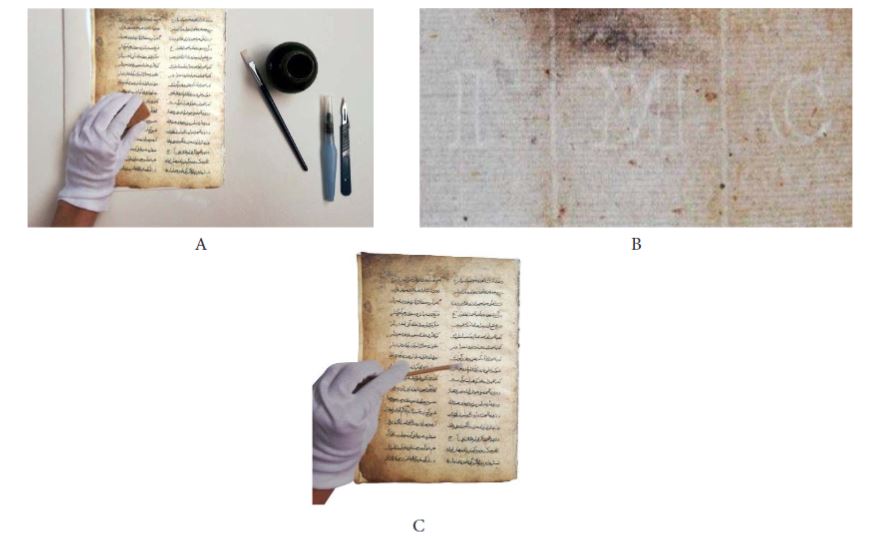

Proces restauracije započeo je numerisanjem stranica, a zatim rastavljanjem knjižnog bloka po formama. Potom se pristupilo mehaničkom čišćenju svake stranice rukopisa (margine, a zatim dijelovi između teksta) vulkaniziranom gumicom i gumicom u prahu (Holmes, 2015). Skalpelima su površinski očišćeni produkti insekata te skinute trake prethodne reparacije. Masne mrlje u uglu stranica nastale od čestog listanja rukopisa bez primjene rukavica uklonjene su električnom gumicom. Prilikom suhog čišćenja na pojedinim stranicama knjižnog bloka primijećeni su vodeni žigovi. Identificirani žig na početku rukopisa sadrži inicijale “IMC” (pojavljuje se još kao “IMG”) te potiče od papira pravljenog na osmanskom području na kojem su pisali kaligrafi iz 17. stoljeća (Kropf, 2015). Drugi identificirani vodeni žig se sastojao iz dva dijela – sidro i šestokraka zvijezda iznad sidra. Sidro je bilo čest motiv među italijanskim proizvođačima papira u 16. i 17. stoljeću. Sidro se moglo crtati iz jednog ili dva dijela, pri čemu su česti motivi iznad sidra bili zvijezda, list, cvijet, prsten i inicijali (Kropf, 2015). Nakon završenog mehaničkog čišćenja započeta je faza pranja papira. Prije samog pranja papira izvršeni su testovi vodorastvorivosti crne i crvene tinte prisutne na rukopisu, pri čemu je utvrđeno da su obje tinte vodorastvorive, pa se rastvor etanola i destilovane vode (3 : 1) pokazao kao najefikasnija metoda čišćenja. Pri pranju, stranice rukopisa su postavljene na tzv. upijač papir, kako bi se vlaga i prljavština iz stranica potpuno apsorbovala. Nakon što su vodene mrlje očišćene, pristupilo se obostranom čišćenju listova rastvorom metilceluloze u vodi (1 : 5) da bi papir postao čvršći i pri čemu se lanci celuloze produžavaju molekulama metilceluloze ojačavajući vlakna (Mladićević et al., 2015; Ašler & Rakić-Mutak, 2015).

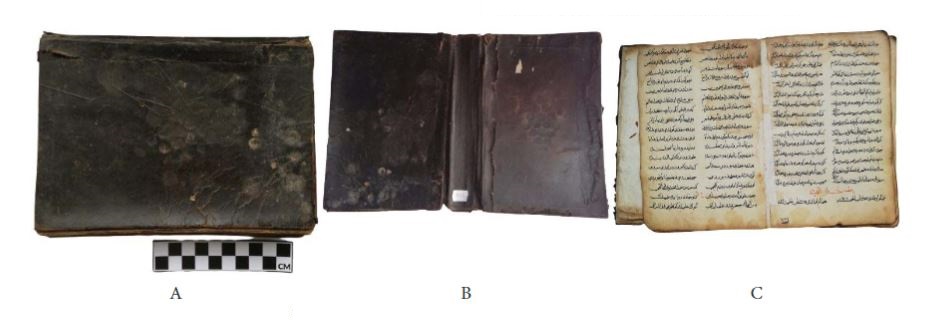

Slika 2. A) Mehaničko čišćenje stranica; B) Vodeni žig – inicijali “IMC”; C) Mokro čišćenje stranica

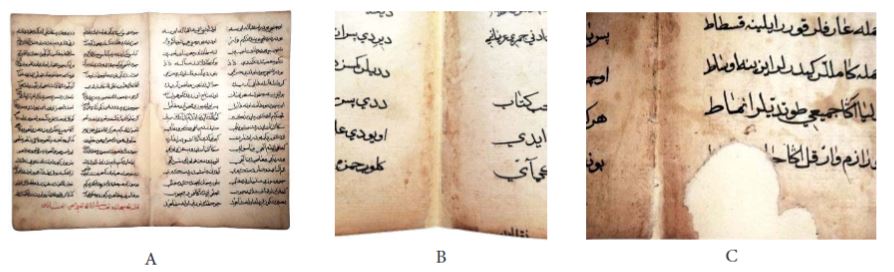

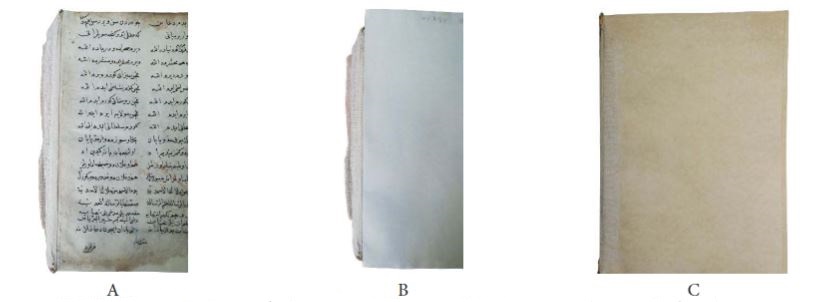

Restauracija papira

Nakon sušenja stranica pristupilo se ručnoj restauraciji zbog dijelova koji nedostaju – japanskim papirom. Japanski papir je najmanje invazivan materijal, pa se zbog svoje pH neutralnosti koristi pri restauraciji. Na rukopisu je primijenjen 22-gramski papir ( Kinugawa ivory, 22 g/m2, 100% Kozu) , toniran oker žutom bojom koja je približna boji izvornog papira. Oker žuta je prirodni anorganski pigment koji se umjetno dobija taloženjem željeznih soli na kredu, pa se kalciniranjem dobija željeni ton. Za postizanje željene nijanse korištena je vrlo malena količina pigmenta, zbog njegove vrlo dobre postojanosti. Kao metoda restauracije papira korištena je ručna restauracija japanskim papirom (Mizumura et al., 2017; Masuda, 2016). Japanski papir ima izvanrednu elastičnost, mehaničku otpornost i stabilnost zbog svojih dugih vlakana, te tretiran metilcelulozom ili škrobom daje papiru stabilnost i otpornost na toplotu i posljedice UV zračenja (Artal-Isbrand, 2018; Tkalčec et al., 2016). Pri restauraciji, vodenim kistom smo ocrtavali japanski papir tako da oblikom prati rub oštećenja na listu. Na ovaj način lijepljenjem japanskog na izvorni papir uklonjena je razlika u debljini dvaju vrsta papira (Kreigher-Hozo, 1991; Artal-Isbrand, 2018; Tkalčec et al., 2015).

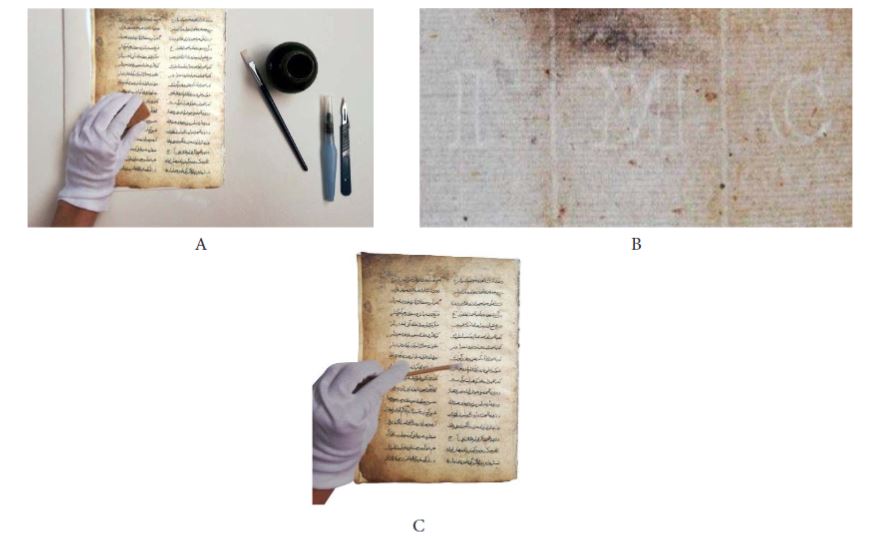

Slika 3. A) Izgled restaurirane stranice rukopisa; B) i C) Detalj restaurirane stranice

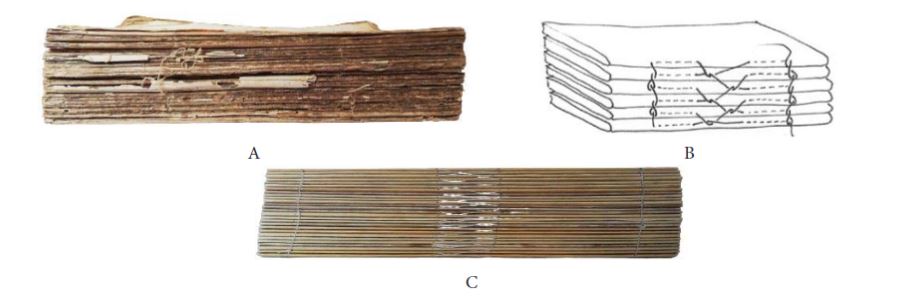

Ušivanje knjižnog bloka

Ispresovani listovi su nakon sušenja i ravnanja u mehaničkoj knjigovezačkoj presi ručno obrezani, pri čemu je odstranjen samo višak dodanog japanskog papira, dok su dimenzije knjižnog bloka rukopisa ostale potpuno nepromijenjene. Listovi su zatim ponovo presloženi u forme prema numeraciji i šivani na tzv. link-stitch (lančani uvez) sa 4 faze ušivanja. To je način koji osigurava ravan hrbat koji je bio ključni u islamskom i turskom knjigovestvu (Szirmai, 1999; Scheper, 2018).

Lančano ušivanje na 4 faze počelo je provlačenjem svilenog konca kroz prvu šivaću rupu, izlaskom na drugu, gdje konac pravi petlju oko konca prethodne forme, a zatim opet ulazi na treću šivaću rupu i kontinuirano na unutrašnjoj strani stranica prolazi sve do četvrte šivaće rupe. Konac se iz četvrte šivaće rupe izvuče i veže za konac prethodne forme. Pri nedostatku konca, novi konac je vezan u unutrašnjosti forme (nikada na hrptu) na stari konac (Szirmai,1999; Scheper, 2018). Nakon što su forme ušivene, cijeli uvez je premazan škrobnim ljepilom i ostavljen da odstoji 24 sata. Zatim se na uvezani knjižni blok zalijepio komad knjigovezačkog organtina koji ima dvojaku ulogu – stabilizuje knjižni blok i ujedno je podloga za primarno šivanje ukrasne trake.

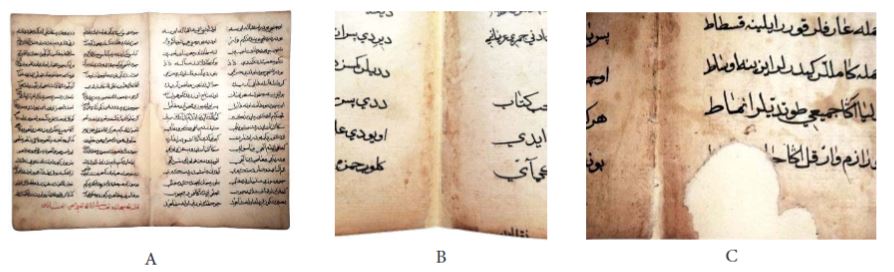

Slika 4. A) Izgled knjižnog bloka prije restauracije; B) Shema link-stitch ušivanja (Scheper, 2018);

C) Knjižni blok nakon restauracije formi i ušivanja

Predlist i zalist

Nakon ušivanja, pripremljen je forzec (predlist i zalist), koji je zalijepljen za knjižni blok. Osnovna funkcija forzeca je da spaja knjižni blok sa koricama i pri tome štiti izravni kontakt korica i pisanog teksta. Papir koji je upotrijebljen kao forzec gramažom je bio veći od izvornog papira, te se smjer vlakana morao podudarati sa knjižnim blokom da bi se spriječilo savijanje korica (Hodžić, 2020).

Slika 5. A) Knjižni blok i hrbat prije lijepljenja predlista i zalista; B) i C) Knjižni blok i hrbat nakon što je predlist zalijepljen

Kapitalna / ukrasna traka

Kapitalna traka se sastoji od dva “slijepa” šivenja (primarnog i sekundarnog), te ukrasnog veza. Rukopisi koji kroz historiju nisu posjedovali sekundarni i ukrasni vez, neizostavno su imali primarno šivenje (Scheper, 2018). Sekundarno šivenje je suštinski priprema za ukrasno šivenje koje se veze preko tzv. jastučića. Jastučić je najčešće tanki komad trake od kože koji se lijepi na vrh hrbata knjižnog bloka. Prvi korak vezenja jeste da jedan od konaca svežemo za iglu, dok je drugi svezan na ostatak konca iz sekundarnog šivenja. Zatim se sa oba konca veze tzv. cik-cak vez koji je ponavljan sve dok jastučić nije bio potpuno prekriven koncem (Scheper, 2018; Szirmai, 1999).

Slika 6. A) Primarno šivenje kapitalne trake; B) Sekundarno šivenje trake sa jastučićem; C) Završeno sekundarno šivenje i početak veza; D) Izvezena kapitalna traka

Uvez

Korice rukopisa Aṭ-Ṭāriqa al-Muḥammadiyya su po izradi klasične korice ukrašene slijepim tiskom kojim nedostaju preklop i klapna. Rukopis slične tematike iz biblioteke tekije Mesudija koji datira iz istog perioda sadrži preklop i klapnu, pa se pretpostavlja da je prethodnom reparacijom preklop potpuno uklonjen. Koža korica rukopisa očišćena je destilovanom vodom i na taj način ujedno omekšana (Kite & Thomson, 2015). Unutrašnje strane korica su također očišćene, te je odstranjen papir koji je nekada imao funkciju forzeca. Nekoliko površinskih lakuna na koricama, koje su posljedica udarca rukopisa oštrim predmetom ili neprikladnim rukovanjem knjigom, popunjene su japanskim papirom. Nova koža koja je korištena za preklop i klapnu iste je vrste kao i izvorna – ručno štavljena, crna, kozija koža. Kroz historiju kozija koža je korištena za najkvalitetnije radove, jer je bila iznimno izdržljiva, sjajna i dobro zrnasta, te se mogla bojiti (Pearson et al., 2006; Hadžimejlić, 2011; Kite & Thomson, 2006). Ova vrsta kože je vrlo tanka (< 1 mm), tako da se razlike u debljini originalne i nove kože ne primjećuju. Korice su stajale do potpunog sušenja u knjigovezačkoj presi, a koža se impregnirala lanenim uljem. Laneno ulje se dobija ekstrakcijom sjemenki lana i predstavlja spoj tekućih i čvrstih glicerida oleinske, linolne i linoleinske masne kiseline. Koristi se za vraćanje fleksibilnosti i “hrani” suhu i ispucalu kožu, te se nanosi u više slojeva sve dok koža ne postane sjajna i glatka (Kreigher-Hozo, 1991; Ali-Hassan, 2016; Kite & Thomson, 2006). Korice su djelimično posjedovale već izgubljeni ukras koji je nastao slijepim tiskom geometrijskog motiva romba. Romb ispunjavaju minijaturne rozete. Kod ove vrste uveza motivi se otiskuju na kožu korica reljefno i ostaju u boji kože korica (Hadžimejlić, 2011). Korice su prije postavljanja knjižnog bloka premazane želatinom kako bi dobile sjaj i glatkoću. Na završen rukopis ponovo je zalijepljen inventarni broj, te je priložen evidencijski karton.

Slika 7. A) Izgled forzeca; B) Restaurirani rukopis; C) Preklop i klapna rukopisa; D) Korice rukopisa nakon restauracije; E) Izgled kapitalne trake i hrpta nakon restauracije

Zaključak

Očuvanjem kulturnohistorijskog naslijeđa svjedoči se i štiti identitet jednog naroda koji je postojao na nekom području, pa je knjiga ta koja prenosi njihova znanja i poruku iz prošlosti u budućnost. Konzervatorima i restauratorima, međutim, nije važan samo sadržaj knjige već i metode, tehnike i materijali koji su korišteni za njenu izradu, kao i historijat njenog nastanka. Zbog toga je sadržaj rukopisa digitalizovan, a knjižni blok i uvez restaurirani i konzervirani kako bi se očuvali za buduće naraštaje. Konzervatorsko-restauratorskim postupcima su uklonjene nečistoće, papir je ručno restauriran kako ne bi došlo do povećanja dimenzija listova i samim tim knjižnog bloka, te je papir toniran u boju originalnih listova. Korice rukopisa su restaurirane i vraćena im je funkcionalnost, kao i estetska vrijednost. Restauracijom manuskripta se nastojao usporiti proces starenja i vratiti stabilnost i funkcionalnost. Prostor u kojem bi se skladištio rukopis trebao bi imati umjerenu sobnu temperaturu (16–20°C), relativnu vlažnost između 50 i 55%, te ograničeno vrijeme izloženosti ultraljubičastom (UV), infracrvenom (IC) zračenju ili vidljivoj svjetlosti (Krstić, 2000; Lazslo & Dragojević, 2010; Pilipović, 2004). Trajnom brigom, dobrim skladištenjem i pažljivim rukovanjem manuskripti bi se očuvali i zaštitili za buduće generacije.

Introduction

Under the rule of the Ottoman Empire, Sarajevo was one of the largest cultural centres of Europe with a very rich cultural and artistic life. In addition to a large number of elementary schools and madrasas, libraries existed then, as they are today, treasuries of knowledge and guardians of cultural heritage and history. Book in the Ottoman Empire played a very important role in the transmission of knowledge and artistic expression, but it was also a distinct decorative item. Manuscripts were entirely rare and precious artifacts that were given special attention when they were created, written, or copied until they were preserved and deposited. The bookbinding technique developed over the centuries, from writing on papyrus to the high-quality production of leather covers, as evidenced by manuscripts stored in libraries, museums, and private collections throughout Bosnia and Herzegovina. The Oriental manuscript of Aṭ-Ṭāriqa al-Muḥammadiyya copied in 1181/1760 is part of the collection of the Mesudija library in Kaćuni, which contains over 10,000 very rare and valuable works.

The full title of the manuscript is Eṭ-Ṭarîḳatü’l-Muḥammediyye ve’s-sîretü’l-Aḥmediyye’,5 and the original text originates from the 16th century. It was written by a famous scholar Muhammad b. Pir 'Ali al-Birgiwi ar-Rumi Taqiyyuddin6 (929/1573), represents one of the most read Tasawwuf (Sufi) works, which talks about good behavior and the principles of religious life in accordance with the sunnah of Prophet Muhammad, alayhi s-salām, and the Qur’an as the Holy Book in Islam. The work has significant social and historical value and is written in plain, readable, vernacular language. The manuscript text consists of three main parts; each of them has three chapters and is written in the form of questions with answers (İslâm Ansiklopedisi, 2013). Before the actual restoration, detailed photo documentation and a register of the work were carried out.

Description of the condition of the bookblock and binding before the conservation procedure

The bookblock consists of 270 sheets of paper, bound in 27 forms of 10 sheets of paper each. The paper was previously repaired by gluing self-adhesive white strips to the original. Insect products are noticeable on many sheets of paper, while insect remains were found inside the forms. On the pages, the ink is smeared outside the margins and over the text. Before writing of the text, the paper is impregnated, which can be seen by the distinct shine of the sheets of paper. Due to poor storage conditions and the effect of moisture, the paper is in an initial state of degradation. The decoration present on the cover is made as embossing (“blindruck”, blind stamping). The classic leather covers of Islamic bookbinding are missing the fore-edge flap and envelope flap, and due to the previous restoration, they are damaged and do not fit the bookblock. Endpapers, whose basic role is to connect the cover with the bookblock, are completely missing. On the spine, where the organtine stayed glued, threads are visible where the damaged double capital strip is sewn. Two lines of text are written on the inside of the cover. The text is in Turkish in the Arabic script (Naskh), written in two types of ink, black and red. The ink is sensitive to water, which is noticeable by smeared parts of the margins and text.

Figure 1. A), B) and C) The appearance of the manuscript before the restoration

Conservation-restoration treatment on bookblock

Cleaning the bookblock

The restoration process began with the numbering of the pages, and then with the disassembly of the bookblock by form. Afterward, the mechanical cleaning of each page of the manuscript (margins and then the parts between the texts) with a vulcanized smoke sponge and cleaning powder started (Holmes, 2015). Insect products were cleaned from the surface with scalpels, and the strips of the previous repair were removed. Grease stains in the corner of the pages caused by frequent flipping of the manuscript without using gloves were removed with an electric eraser. During dry cleaning, watermarks were noticed on some pages of the bookblock. The identified watermark at the beginning of the manuscript contains the initials “IMC” (also appears as “ IMG”) and originates from the paper made in Ottoman areas on which calligraphers from the 17th century wrote (Kropf, 2015). Another identified watermark consisted of two parts – an anchor and a six-pointed star above the anchor. The anchor was a common motif among Italian paper makers in the 16th and 17th centuries. The anchor could be drawn from one or two parts, with frequent motifs above the anchor being a star, leaf, flower, ring, and initials (Kropf, 2015). After the mechanical cleaning was completed, the paper-washing phase began. Before washing the paper, water solubility tests of the black and red ink present on the manuscript were performed, and it was determined that both inks were water soluble, so a solution of ethanol and distilled water (3 : 1) proved to be the most effective cleaning method. When washing, the pages of the manuscript are placed on the so-called absorbent paper, to completely absorb moisture and dirt from the pages. After the water stains were cleaned, the paper sheets were cleaned on both sides with a solution of methylcellulose in water (1 : 5) to make the paper stronger whereby the cellulose chains are extended with methylcellulose molecules, strengthening the fibers (Mladićević et al., 2015; Ašler & Rakić-Mutak, 2015).

Figure 2. A) Mechanical cleaning of pages; B) Watermark – Initials “IMC”; C) Wet cleaning of pages

Paper restoration

After drying the paper sheets, manual restoration began because of the missing parts with the use of Japanese paper. Japanese paper is the least invasive paper, therefore, due to its pH neutrality; it is used in restoration. The 22-gram paper was used on the manuscript ( Kinugawa ivory, 22 g/m2, 100% Kozu) , tinted with ochre yellow, which is close to the colour of the original paper. Ochre yellow is a natural inorganic pigment that is obtained artificially by the deposition of iron salts on chalk, and then the desired tone is obtained by calcination. To achieve the desired shade, a very small amount of pigment was used, due to its very good durability. As a method of paper restoration, manual restoration with Japanese paper was used (Mizumura et al., 2017; Masuda, 2016). Japanese paper has extraordinary elasticity, mechanical resistance, and stability due to its long fibers, and treated with methylcellulose or starch, gives the paper stability and resistance to heat and the effects of UV radiation (Artal-Isbrand, 2018; Tkalčec et al., 2016). During the restoration, Japanese paper was outlined with a water brush so that the shape follows the edge of the damage on the sheet of paper. In this way, by gluing the Japanese paper on the original paper, the difference in the thickness of the two types of paper was removed (Kreigher-Hozo, 1991; Artal-Isbrand, 2018; Tkalčec et al., 2015).

Figure 3. A) Layout of the restored manuscript page; B) and C) Detail of the restored page

Sewing a bookblock

The pressed sheets of paper, after drying and straightening in a mechanical bookbinding press, were trimmed by hand, whereby only the excess of added Japanese paper was removed, while the dimensions of the bookblock of the manuscript remained completely unchanged. The sheets were then folded again into forms, according to the numbering, and sewn with the so-called link-stitch with 4 phases of sewing. It is a way to ensure a straight spine that was crucial in Islamic and Turkish bookbinding (Szirmai, 1999; Scheper, 2018). Link-stitch with 4 phases begins with broaching the silk thread through the first sewing hole, exiting to the second where the thread makes a loop around the thread of the previous form, and then again entering the third sewing hole and continuously on the inner side of the pages and goes all the way to the fourth sewing hole. The thread is pulled out of the fourth sewing hole and tied to the thread of the previous form. If there is no thread, the new thread is tied inside the form (never on the spine) to the old thread (Szirmai, 1999; Scheper, 2018). After the forms are sewn, the entire binding is coated with starch glue and left to rest for 24 hours. Then, a piece of bookbinding organtine was glued to the bound bookblock, which has a dual role – it stabilizes the bookblock and is also the base for the primary sewing of the decorative tape.

Figure 4. A) The appearance of the bookblock before the restoration; B) Scheme of link-stitch sewing (Scheper, 2018); C) Bookblock after form restoration and sewing;

Endpapers

After sewing, endpapers (front page and back page) were prepared and glued to the bookblock. The basic function of the endpapers is to connect the bookblock with the cover and at the same time protect the direct contact between the cover and the written text. The paper used as the endpapers were heavier than the original paper, and the direction of the fibers had to match the bookblock to prevent the cover from bending (Hodžić, 2020).

Figure 5. A) Bookblock and spine before gluing the endpapers; B) and C) Bookblock and spine after the gluing of the endpapers

Endbands

Endbands consist of two “blind” stitches (primary and secondary endband sewing) and decorative embroidery sewing. Manuscripts that throughout history did not have secondary endband sewing and decorative embroidery inevitably had a primary stitch. Manuscripts that throughout history did not have secondary and decorative embroidery inevitably had primary stitch (Scheper, 2018). The secondary stitch is essentially a preparation for decorative embroidery, which is connected through the so-called endband core. The endband core is usually a thin piece of leather tape that is glued to the top of the spine of the bookblock. The first step of embroidery is to tie one of the threads to the needle, while the other is tied to the rest of the thread from the secondary embroidery. Then both threads are sewed with a so-called Islamic chevron endband pattern which is repeated until the endband core is completely covered with thread (Scheper, 2018; Szirmai, 1999).

Figure 6. A) Primary embroidery of the capital band; B) Secondary embroidery of the band with a pad; C) Finished secondary embroidery and beginning of sewing; D) Embroidered capital band

Binding

The cover of the Aṭ-Ṭāriqa al-Muḥammadiyya manuscript is a classical cover decorated with blind printing that lacks a fore-edge flap and envelope flap. A manuscript with a similar theme from the library of the Mesudija tekke dating from the same period contains a fore-edge flap and envelope flap, so it is assumed that the flap was completely removed during the previous repair. The leather cover of the manuscript was cleaned with distilled water and thus softened at the same time (Kite & Thomson, 2015). The inside covers were also cleaned, and the paper that once had the function of endpapers was removed. A few surface lacunae on the cover, which are the result of hitting the manuscript with a sharp object or improper handling of the book, have been filled with Japanese paper. The new leather used for the fore-edge flap and envelope flap is the same type as the original – hand-tanned, black, goat leather. Throughout history, goat skin was used for the highest quality works, because it was extremely durable, shiny and well-grained, and could be dyed. (Pearson et al., 2006; Hadžimejlić, 2011; Kite & Thomson, 2006). This type of skin is very thin (< 1 mm) so the differences in the thickness of the original and new skin are not noticeable. The covers were left to dry completely in a bookbinding press, and the leather was impregnated with linseed oil. Linseed oil is obtained by extracting flax seeds and is a combination of solid triglycerides of oleic, linoleic, and linoleic acid. It is used to restore flexibility and “nourish” dry and cracked skin, and it is applied in several layers until the skin becomes shiny and smooth. (Kreigher-Hozo, 1991; Ali-Hassan, 2016; Kite & Thomson, 2006). The cover partially possessed an already lost decoration that was created by a blind printing of a geometric rhombus motif. The rhombus is filled with miniature rosettes. With this type of binding, the motifs are printed on the leather of the cover in relief and remain in the colour of the leather of the cover (Hadžimejlić, 2011). Before placing the bookblock, the covers are coated with gelatine to give them shine and smoothness. The accession number was pasted on the completed manuscript again, and the record card was enclosed.

Figure 7. A) Appearance of the endpapers; B) Restored manuscript; C) Fore-edge flap and envelope flap of the manuscript; D) Manuscript cover after restoration; C) Appearance of capital band and spine after restoration

Conclusion

By preserving the cultural and historical heritage, the identity of a people that existed in a certain area is witnessed and protected, so it is the book that transmits their knowledge and message from the past to the future. For conservators and restorers, however, not only the content of the book is important, but also the methods, techniques, and materials used for its creation, as well as the history of its creation. For this reason, the content of the manuscript was digitized, and the bookblock and binding were restored and conserved in order to preserve them for future generations. Impurities were removed by conservation-restoration procedures, and the paper was restored by hand in order not to increase the dimensions of the sheets of paper and thus the bookblock, and the paper was toned in the colour of the original sheets of paper. The covers of the manuscript have been restored and their functionality and aesthetic value have been restored. The restoration of the manuscript sought to slow down the aging process and restore stability and functionality. The space where the manuscript would be stored should have a moderate room temperature (16–20°C), relative humidity between 50 and 55%, and limited time of exposure to ultraviolet light (UV), infrared (IC) radiation, or visible light (Krstić, 2000; Lazslo & Dragojević, 2010; Pilipović, 2004). With constant care, good storage, and careful handling, the manuscripts would be preserved and protected for future generations.

Bibliografija / Bibliography

Lazslo, Ž., & Dragojević, A. (2010). Priručnik preventivne zaštite umjetnina na papiru. Zagreb: Crescat – Muzejski dokumentacijski centar – Hrvatski restauratorski zavod.

Pilipović, D. (2004). Konzerviranje i restauriranje papira 4. Grafički materijal: Uzroci oštećenja papira. Ludbreg – Zagreb: Hrvatski restauratorski zavod.

Tkalčec, M. M., Bistričić, L., & Leskovac, M. (2016). Influence of adhesive layer on the stability of kozo paper. Cellulose 23(1), 853-872. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10570-015-0816-7