INTRODUCTION

Lung cancer (LC) is the most common primary malignant tumor worldwide and the rates of incidence and mortality of LC are increasing every year. About 2.2 million new cases of LC occurred and 1.7 million deaths resulted from LC worldwide in 2020, which was the highest among all types of cancer (1). In the clinic, LC is divided into small cell lung carcinoma (SCLC) and non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC), in which NSCLC and SCLC account for 85 and 15 % of all LC cases, resp. (2).

The treatment approaches of LC patients include surgery, chemotherapy, targeted therapy, immunotherapy, etc. Chemotherapeutic drugs are widely applied in the treatment of LC (3). However, chemotherapy often leads to adverse effects in LC patients, such as vomiting and diarrhea. By targeting specific variations of genes and proteins of cancer cells, targeted therapy presents better therapeutic effects, nearly without side effects. For example, gefitinib (an epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, EGFR-TKIs) prolonged the median progression-free survival (PFS) of NSCLC patients with EGFR mutations from 5.4 months to 10.8 months and reduced the incidence of severe toxic effects from 71.7 to 41.2 % compared to chemotherapy (4, 5). Additionally, checkpoint inhibitor-based immunotherapy could prolong the median PFS of NSCLC patients with high expression of PD-L1 from 6.0 months to 10.3 months (6). However, targeted therapy and immunotherapy were only effective for part of LC patients, and all of the patients receiving TKIs became drug-resistant. It is urgent to develop novel anti-LC drugs and reveal the underlying molecular mechanisms.

Recent studies showed that some natural compounds extracted from natural herbs, such as ligustilide, polydatin, 6-gingerol, and tanshinone IIA, exhibited antitumor activity against different kinds of cancer (7). In addition, numerous natural compounds could enhance the immune function of the body, reverse multi-drug resistance, as well as prolong the overall survival (OS) of cancer patients (8). For example, etoposide is a semi-synthetic derivative of podophyllotoxin, a non-alkaloid lignin isolated from the roots and rhizomes of Podophyllum peltatum (9). In a phase III trial, the median OS of 95 patients with stage Ⅲ NSCLC treated with etoposide plus cisplatin reached 23.3 months (10). Another phase Ⅲ trial has shown that albumin-bound paclitaxel nanoparticles could prolong the median OS of patients with NSCLC to 16.2 months compared with the docetaxel group (13.6 months) (11). In the preclinical stage, some natural compounds also exhibited antitumor effects against LC. For instance, ligustilide extracted from traditional Chinese herbs Angelica sinensis and Ligusticum chuanxiong, could significantly inhibit proliferation and induce apoptosis of human NSCLC cell lines A549 and H1299 in vitro and in vivo (12). Additionally, polydatin extracted from the perennial herb Polygonum cuspidatum, could suppress the proliferation of NSCLC cells by inhibiting the activation of NLRP3 inflammasome via the NF-κB pathway (13).

Current therapeutic strategies among natural compounds focus on the suppression of tumorigenesis and progression via modulating multiple signaling pathways to induce apoptosis, arrest the cell cycle, and inhibit angiogenesis and invasion (14). Apoptosis is a highly regulated process of cell death triggered by various endogenous or exogenous stimuli, which is essential in development, homeostasis, and aging. For instance, sanguinarine induced apoptosis via downregulation of the constitutively active JAK/STAT pathway in NCI-H-1975 and HCC-827 NSCLC cell lines (15). The other natural compounds lanatoside C, tubeimoside-1, lotus leaf flavonoids, and ebractenoid F are also found to exhibit antitumor activity in LC (Table Ⅰ).

Table Ⅰ. Application of natural compounds in tumor treatment

Medicarpin (MED) is an isoflavone compound isolated from alfalfa (16), which is usually used in traditional medicine. Its molecular formula is C16H14O4 (Fig. 1) (17). Recent studies reported that MED contributed to bone sparing effect in ovariectomized mice via stimulation of osteoblast differentiation (18) and inhibition of osteoclastogenesis (19). Importantly, MED presented antitumor activity. For instance, MED-induced cell apoptosis of the doxorubicin-resistant P388 leukemia cells, which is a monocyte/macrophage-like cell line derived from mouse lymphoma (20). Furthermore, MED sensitized myeloid leukemia cells K562 and U937 to tumor necrosis factor α-related apoptosis (21). In addition, MED could upregulate AKT and tumor-suppressor gene PTEN to activate the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (22). Although the natural biological function of MED was identified in bone formation, the therapeutic effects of MED on LC and the underlying antitumor mechanisms remain obscure. The purpose of this study is to determine whether MED exerts antitumor activity in lung cancer and investigate the potential antitumor mechanisms of MED in LC.

Fig. 1. Chemical structure of medicarpin.

EXPERIMENTAL

Cell culture and reagents

A549 and H157 LC cell lines, which were obtained from Procell Life Science & Technology Co., Ltd. (China) were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (HyClone, USA) containing 10 % fetal bovine serum (Gibco, USA), 1 % penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco), which was maintained at 37 ℃ in 5 % CO2 environment.

Medicarpin was purchased from Desite Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (China, purity of ≥ 98.0 %). Medicarpin (2.7 mg) was dissolved in 200 μL dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) to obtain the stock solution (50 mmol L–1) and stored at –20 ℃.

Cell counting kit-8 assay

Cells were resuspended and cultured into 96-well culture plates at a density of 5,000 cells per well. The stock solution (50 mmol L–1) was diluted 100, 200, 400, 800, and 1600 times with RPMI-1640; cells were incubated with various concentrations of MED for 24 or 48 h. Cell viability was analyzed by cell counting kit-8 (CCK8, Beyotime, China) with DMSO as a control sample.

Cell cycle assay

A549 and H157 cells were cultured in 6-well culture plates treated with 206.8 μmol L–1 and 102.7 μmol L–1 MED for 48 h, resp. Then cells were collected and fixed by pre-cooled 70 % ethanol overnight at –20 ℃. The cells were washed with PBS and stained with 50 μg mL–1 RNase A (Solarbio, China) and 0.025 μg propidium iodide (PI) according to the cell cycle assay kit (Solarbio). The cell cycle distribution was measured by flow cytometry FACS Calibur system (BD Biosciences, USA).

Cellular apoptosis assay

The apoptosis of LC cells with MED treatment was determined by Annexin V-FITC/PI double staining. A549 and H157 cells were cultured in 6-well culture plates treated with 206.8 and 102.7 μmol L–1 MED for 48 h, and with 290.8 and 125.5 μmol L–1 for 24 h, resp. The Annexin V-FITC kit (Beyotime) was used according to the manufacturer's instructions. The cells were washed with PBS, digested, collected, and re-suspended in 195 μL binding buffer. Then, 5 μL Annexin V-FITC and 10 μL PI were added, and the cells were incubated for 20 min at room temperature in the dark. The cells were re-suspended in 300 μL PBS and analyzed using the flow cytometry (see above).

Live and dead cell detection

A549 and H157 cells were cultured in a glass bottom cell culture dish treated with 206.8 μmol L–1 and 102.7 μmol L–1 MED for 48 h, resp. The Calcein-AM/PI double staining kit (Beyotime) was used according to the manufacturer's instructions. The cells were washed with PBS and resuspended with an appropriate volume of Calcein-AM working solution. The cells were then stained with PI for 30 min at 37 ℃ in the darkness. The images were shown by a confocal laser scanning microscope (Leica, Germany), in which live cells were stained by Calcein-AM (green) and dead cells were labeled by PI (red).

Quantitative real-time PCR

To identify the molecular mechanisms of MED against LC, apoptosis-related genes ( caspase-3 ( Casp3), caspase-10 ( Casp10), BAX, Bak1, CYCS) (23-25), anti-apoptotic gene ( Bcl-2), proliferative genes ( Bid, NF-κB) (26-28) and tumor suppressor gene ( TP53) (29, 30) were analyzed under the treatment by MED in A549 and H157 cells. Total RNA was extracted from A549 and H157 cells by using the RNAprep pure cell kit (DP430, Tiangen, China), and 1 μg RNA was transcribed to cDNA using FastKing RT kit (KR116-02, Tiangen) following the manufacturer's instructions. PCR master mix was used to carry out the real-time PCR according to the manufacturer's protocols. The primer sequences of Casp3, Casp10, Bcl-2, BAX, Bak1, Bid, CYCS, NF-κB1, TP53, and GAPDH were obtained from Tsingke Biotechnology Co., Ltd. and listed in Table Ⅱ. Relative gene expression values were obtained using the 2-∆∆CT method and normalized using controls. The primer sequences used in Real-time PCR reactions were as follows in Table II.

Table Ⅱ. Primer sequences for real-time PCR

Western blot analysis

The cells were lysed by using RIPA buffer (R0010, Solarbio) with 1 mmol L–1 phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) (P0100, Solarbio). The proteins were collected and concentrations were detected by a BCA protein concentration assay kit (PC0020, Solarbio) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Electrophoresis was performed with sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), and protein was transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes (Millipore, USA). Then the membranes were blocked in 5 % nonfat milk at room temperature for 1 h, followed by incubating with the appropriate primary antibody at 4 °C overnight. After washing three times in 1×Tris-buffered saline and Tween 20 (TBST) buffer, the secondary antibodies were added and incubated at room temperature for 1 h. The membranes were washed in 1×TBST buffer three times for about half an hour each time. Finally, the proteins were detected by the ECL kit (PE0010, Solarbio). The primary antibodies were as follows: β-actin (1:5000; Cell Signaling Technology, USA), BAX (1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology), Bak1 (1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology), Bcl-2 (1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology), Casp3 (1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology) and Bid (1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology). The secondary antibodies were as follows: goat anti-mouse IgG (H+L)-horseradish peroxidase (HRP) (1:3000, Tianjin Sungene Biotech Co., Ltd., China), goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L)-horseradish peroxidase (1:3000, Tianjin Sungene Biotech Co.). Protein bands were analyzed with Image J software. The results of each protein were obtained by detecting three groups of different samples.

Animal experiments

In order to establish a xenograft mouse model, ten female BALB/c nude mice (6 weeks old) were injected with 6 × 106 A549 or 6 × 106 H157 cells subcutaneously into the back of mice. When tumors reached a diameter of 3 to 5 mm, mice were randomly divided into two groups ( n = 5) and administered intraperitoneally 10 mg kg–1 MED or PBS every three days, resp. Tumor size was measured and calculated by the formula: volume = (length × width2)/2. Finally, tumor-bearing mice injected with A549 or H157 were sacrificed on the 30th day and 15th day, resp. The volume of tumors was recorded.

The animal study was reviewed, approved, and carried out in compliance with the Animal management rules of the China-Japan Friendship Hospital having ethics approval number 2021-42-K26.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted by using GraphPad Prism 5.0 software. Statistical differences were detected by Student’s t-test between two groups and one-way ANOVA for three or more groups. The experiment was repeated three times, and the statistical results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). A p-value < 0.05 was used as the criterion for statistical significance.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Medicarpin on lung cancer cells proliferation and cell cycle arrest

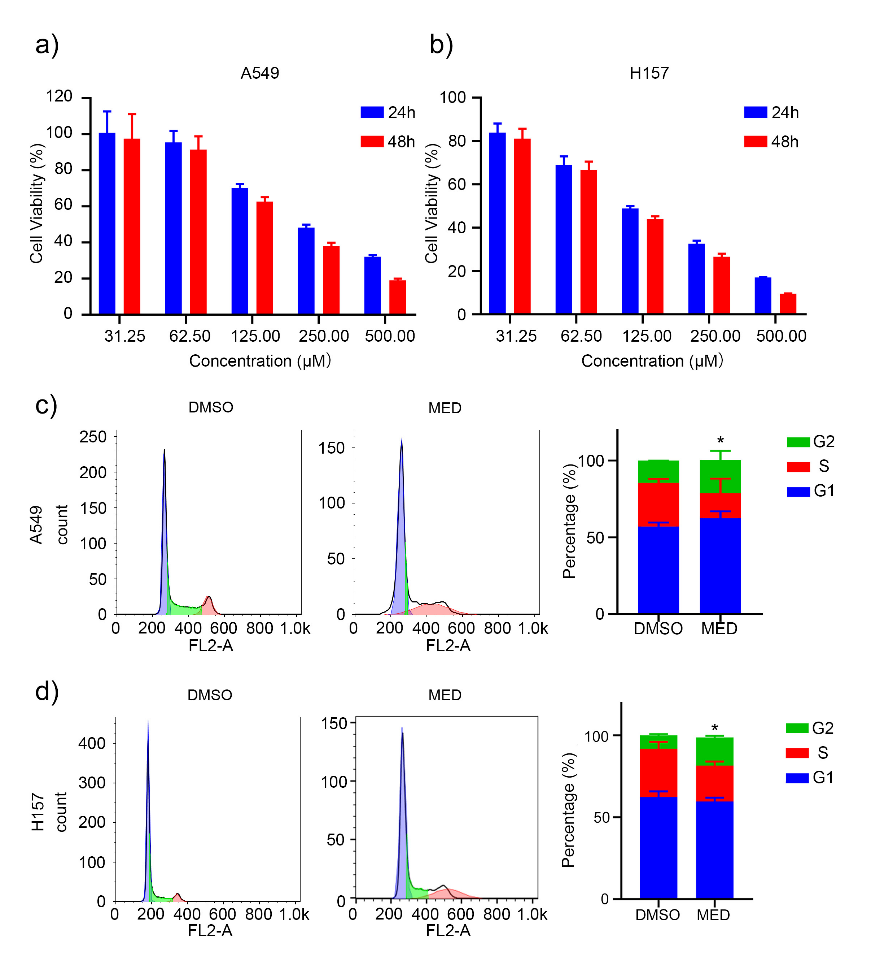

MED significantly inhibited the proliferation of A549 and H157 cells in a concentration- and time-dependent manner (Figs. 2a and 2b). Furthermore, the half maximal inhibitory concentration ( IC50) value of MED on A549 cells at 24 h and 48 h was 290.8 ± 23.2 and 206.8 ± 13.2 μmol L–1, resp., whereas for H157 cells at 24 h and 48 h it was 125.5 ± 9.2 and 102.7 ± 13.2 μmol L–1, resp. These results indicated that MED can inhibit the proliferation of LC cells in vitro.

The cell cycle distribution of A549 and H157 cells was analyzed via propidium iodide staining. MED affected the cell cycle and increased the proportion of the G2 phase of both A549 and H157 cells (Figs. 2c,d). There weren’t significant differences at G1 and S phasea between DMSO and MED groups.

Fig. 2. Effects of medicarpin on proliferation and cell cycle of A549 and H157 cell lines: a) and b) A549 and H157 cell lines proliferation depending on concentration and culture time; c) and d) percentage of G1, S and G2 phase of A549 and H157 cell lines with MED treatment. Data are displayed as mean ± SD of three independent experiments. Statistically significant difference: *p < 0.05.

Medicarpin and apoptosis of lung cancer cells

MED could induce the apoptosis of A549 and H157 cells in a time-dependent manner (Figs. 3a,b). Specifically, the proportion of apoptotic cells was 16.3 ± 4.7 % and 54.7 ± 1.6 % in A549 cells, 21.1 ± 1.8 % and 46.2 ± 5.7 % in H157 cells after 24 and 48 h, resp. Compared to DMSO, MED led to significant cell death of A549 and H157 cells after 24 h (Fig. 3c); the proportion of apoptotic cells induced by MED treatment after 48 h was significantly higher than that after 24 h.

Fig. 3. Effects of medicarpin on apoptosis of A549 and H157 cell lines: a) and b) flow cytometry analysis in A549 and H157 cell lines for 24 h and 48 h (stained by Annexin V -FITC/PI, percentage of apoptotic cells is detected by FACS; c) A549 and H157 cell lines stained by Calcein-AM/PI double staining kit and observed with laser confocal microcopy (scale bar 100 μm). Data are displayed as mean ± SD of three independent experiments. Statistically significant difference: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

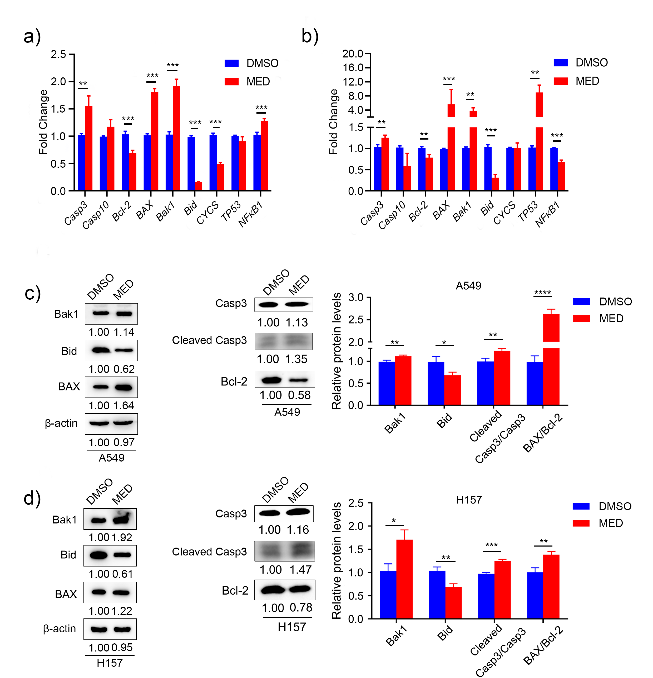

Medicarpin and expression of apoptosis-related genes and proteins

In A549 cells, MED treatment significantly elevated the expression of Casp3, BAX, Bak1, and NF-κB, and decreased the expression of Bcl-2, Bid, and CYCS compared to DMSO (Fig. 4a). In H157 cells, MED treatment significantly elevated the expression of Casp3, BAX, Bak1, and TP53, and decreased the expression of Bcl-2, Bid, and NF-κB compared to DMSO (Fig. 4b). In both A549 and H157 cells, apoptosis-related genes Casp3, BAX, and Bak1 were upregulated, anti-apoptotic gene Bcl-2 and proliferative gene Bid was downregulated. There was no increase in the expression level of CYCS either in A549, and H157 cells with MED treatment. This may be attributed to the increase in the expression level of cytoplasmic CYCS; RT-PCR only detected whole cells and failed to distinguish cytoplasmic CYCS or mitochondrial CYCS. Besides, NF-κB presented different expression trends in A549 and H157 cells with MED treatment, which may be attributed to the heterogeneity of cell lines.

Western blot analysis indicated that the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 was significantly reduced after MED treatment in both A549 and H157 cells. BAX and Bak1, pro-apoptotic proteins, were upregulated after MED treatment. The high ratio of BAX/Bcl-2 led to cell apoptosis. In our study, BAX/Bcl-2 was remarkably increased after MED treatment. Casp3 is an executive apoptotic protein directly contributing to cell death. Here, we found the expression of cleaved Casp3 was significantly upregulated by MED treatment. Finally, Bid as a proliferative protein was remarkably downregulated after MED treatment (Figs. 4c,d).

Fig. 4. Expression levels of apoptosis-related genes and proteins with medicarpin treatment: a) and b) Casp3 Casp10, Bcl-2, BAX, Bak1, Bid, CYCS, TP53 and NF- κB; c) and d) BAX, Bak1, Bcl-2, Casp3 and Bid. Data are displayed as mean ± SD of three independent experiments. Statistically significant difference: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Medicarpin and other natural moieties and tumor growth in vitro and in vivo

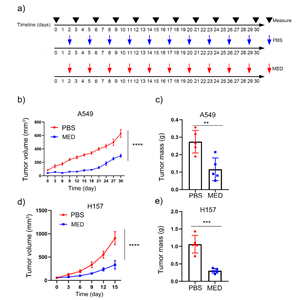

Compared with PBS, MED treatment significantly repressed the tumor growth of A549 cells and reduced the tumor mass of A549 cells in vivo (Figs. 5a-c). Similarly, MED treatment significantly repressed the tumor growth of H157 cells and reduced the tumor mass of H157 cells in vivo (Figs. 5d,e).

Fig. 5. Effects of medicarpin on tumor growth in vivo of: a) A549 and H157 cell lines, PBS or MED; b), c), d) and e) tumor volume and mass of A549 (n = 5) and H157 formed tumors (n = 5). Data are displayed as mean ± SD. Statistically significant difference vs. PBS group: **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Previous studies have shown that several natural compounds have antitumor effects in lung cancer both in vitro and in vivo. For instance, lanatoside C ( IC50 = 56.49 ± 5.3 nmol L –1) (31), tubeimoside-1 ( IC50 = 12.3 μmol L –1) (32), and lotus leaf flavonoids ( IC50 = 282.1 ± 9.63 µg mL –1) (33) were utilized in the treatment of lung cancer. As a natural isoflavone compound, MED exhibited antitumor effects in A549 and H157 cell lines in this study, the IC50 values were 206.8 ± 13.2 μmol L –1 and 102.7 ± 13.2 μmol L –1 for 48 h, resp. Similarly, some studies showed that MED has antitumor effects in other cancer types, such as head and neck squamous cell carcinoma ( IC50 = 80 μmol L –1) (22), leukemia ( IC50 = 90 μmol L –1) (20) and bladder cancer ( IC50 = 79.1 μmol L –1 for EJ-1 and 80.3 μmol L –1 for T24) (16) (Table Ⅰ).

In addition, the dysfunction of the cell cycle usually causes the abnormal proliferation of cancer cells (34). Here, MED could significantly affect the cell cycle by increasing the proportion of the G2 phase in LC cells. Similarly, lanatoside C could induce cell cycle arrest at the G2/M phase in LC A549 cells (31), breast cancer MCF-7 cells (35), hepatocellular carcinoma HepG2 cells (36), and liver cancer Huh7 cells (37). Furthermore, MED inhibited tumor growth and reduced tumor mass of A549 and H157 in vivo. Likewise, MED also inhibited the growth of bladder cancer cell lines T24 and EJ-1 in vivo.

Natural compounds induce antitumor effects through a variety of mechanisms including the modulation of cell proliferation, apoptosis, and cell cycle (38). Apoptosis is a highly conservative suicide program of the cells regulated by a series of cellular genes and proteins (39). MED induced apoptosis of LC cells in this study, as shown by the increase in the proportion of apoptotic cells in MED-treated compared to DMSO groups. Furthermore, MED upregulated the expression of pro-apoptotic genes ( BAX, Bak1, and Casp3) and downregulated anti-apoptotic gene Bcl-2 and proliferative gene Bid. Subsequently, the apoptotic proteins (BAX, Bak1, and Cleaved Casp3) were upregulated, and the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 and proliferative protein Bid were downregulated. Taken together, MED could suppress the proliferation and induce apoptosis of LC cells via activation of mitochondrial-mediated intrinsic pathways. Moreover, other studies demonstrated that MED changed the balance of pro- and anti-apoptotic proteins. For example, MED induced leukemia cell apoptosis through the upregulation of pro-apoptotic protein BAX and downregulation of anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 (20), which were consistent with our study. MED also decreased the expression of cell viability and cell cycle progression ( PDK1) and increased tumor-suppressor gene PTEN to affect PI3K/AKT signal pathway in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (22) (Table Ⅰ).

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, this study showed that MED could inhibit cell proliferation and induce cell cycle arrest of A549 and H157 cell lines in vitro. Furthermore, MED could suppress tumor growth and decrease the tumor mass of LC cells in vivo. In fact, MED could induce cell apoptosis through the mitochondrial-mediated intrinsic apoptosis pathway by upregulating the expression levels of pro-apoptotic genes and proteins (BAX, Bak1, and Casp3) and downregulating the gene and protein expression levels of the anti-apoptotic Bcl-2. The above results indicated that MED may be promising in lung cancer treatment.

In addition to pro-apoptotic mechanisms, MED may suppress the growth of LC cells by the inhibition of nuclear signaling, proteasome pathway, and epigenetic mechanisms, which need further investigation.

Conflict of interests. – The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding. – This work was supported by the Major Research Plan of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (92359202), Scientific and Technological Research Project of Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps (2022AB022), Open Competition to Select the Best Candidates, Key Technology Program for Nucleic Acid Drugs of NCTIB (NCTIB2022HS01016) and the Joint Project of Biomedical Translational Engineering Research Center of Beijing University of Chemical Technology-China-Japan Friendship Hospital (XK2023-21).

Authors’ contribution. – Conceptualization, Z.Y., Z.S., J.S., Z.Y.; investigation, Z.S., L.Y., M.C., M.H., Y.L., R.G., J.Z. and Y.B.; analysis, Z.S., L.Y. and M.C., writing, original draft preparation, Z.S., L.Y. and M.C., writing, review and editing, ZY, HW, JW, CY, JL, RC and QZ, JS, ZY.