INTRODUCTION

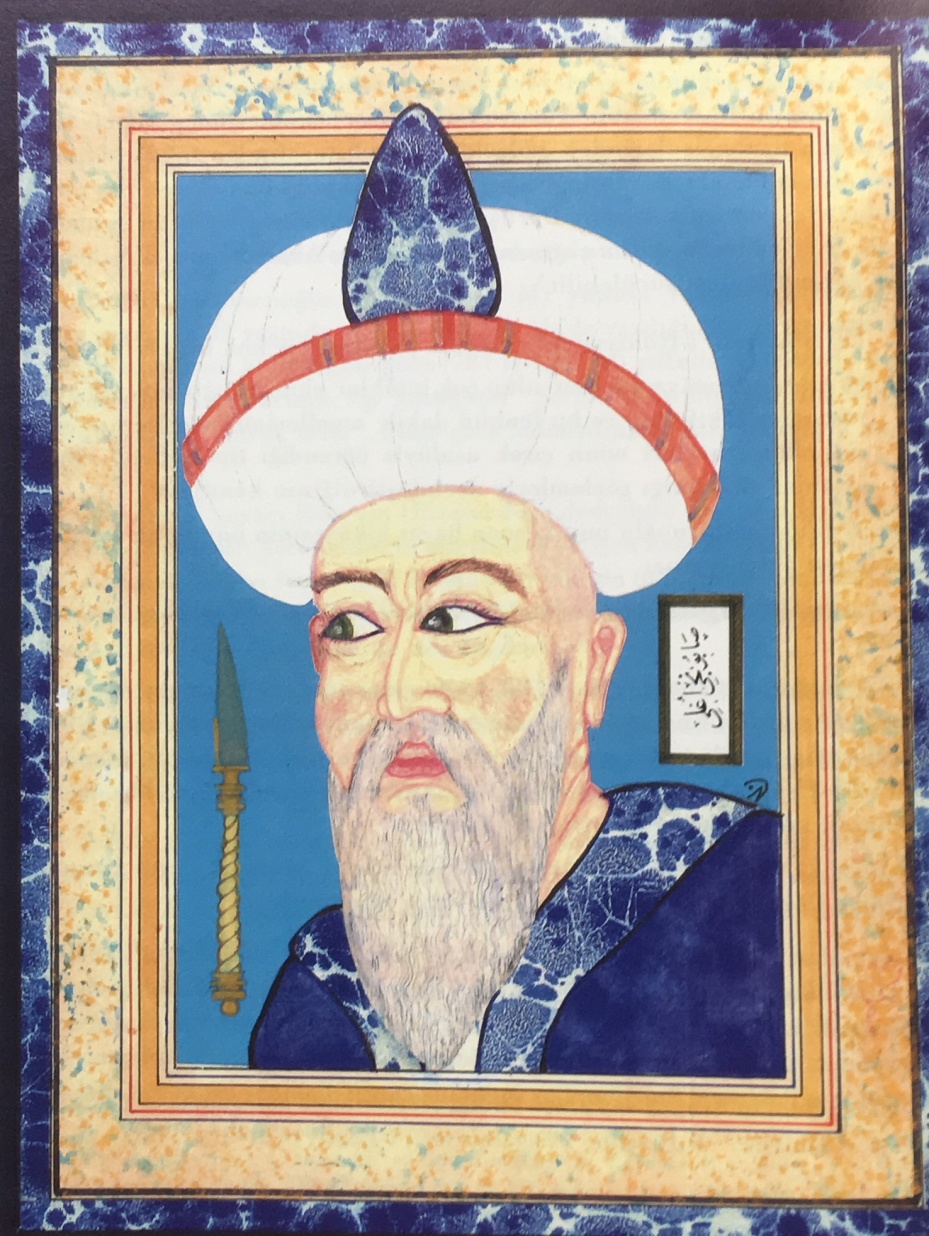

Although, official documents have been lost in time, Şereffeddin Sabuncuoğlu is thought to have lived between the years 1386 and the 1470’s. This estimate is based on his writings and the information that can be gleaned there from including the medical masterpiece that was completed before his dead. Perhaps unsurprisingly, no grave or tomb has been found for him (Sabuncuoğlu, 1465; Uzel & Süveren, 2000; Uzel, 2020) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Şereffeddin Sabuncuoğlu (1386 - 147?), depicted by Ilter Uzel.

Despite this uncertainty about his personal life, we can be fairly certain that he was one of the more skilled surgeons of the Ottoman period as there is documentary evidence that he conducted surgical operations that can be considered fairly complex for the period. His surgical interventions were in almost every field of modern surgery such as General surgery, Neurosurgery, Urology, Obstetrics & Gynecology, Orthopedics, Thoracic surgery, Vascular surgery, Ear-nose-throat (ENT) and even Ophthalmology (Batirel, 1997;Darçin & Andaç, 2003; Doğan & Tutak, 2021a, 2021b, Er, 2013, Oguz, 2006, Sarban et al., 2005, Verit et al., 2003, Verit & Kafali, 2005). He was almost certainly also an experimental scientist and the author of some medical writings and also a master medical preceptor for his trainers (Uzel, 2020). He lived and worked all his life in the city of Amasya in the centre of the Anatolian peninsula, which at the time was a major agricultural and commercial city in the early Ottoman period and he is thought to have witnessed the great Ottoman conquest of Constantinople. Nevertheless, he never gained the admiration of Fatih Sultan Mehmet, the conqueror, despite his efforts to reach the ruling inner circle where he hoped to present his detailed and illustrated surgical Turkish notes named “Imperial Surgery” (Cerrahiyetü’l-Hanniye). However, this event lack of acknowledgement from the Ottoman leadership did not deter him and he continued to work feverishly. We suspect that the reasons the Ottoman elite ignored him was due to the initial societal transition from military migratory culture to a settled one, which history has shown has preserved very little literature and it is also assumed that the bureaucratic environment at the Palace was not as intellectually oriented as it would become later; secondly, Sabuncuoğlu lived in a provincial Anatolian city far away from Istanbul, which was as now, a truly global city. Lastly, according to the scholars of the era, the main reason was most likely that he produced his masterpieces in Turkish, while classical Arabic and Persian were the preferred literary and academic languages of the Ottoman court instead of the vernacular. Nevertheless, although he knew Arabic and Persian very well, he insisted on writing in Turkish and explained the reason in his own words as “The average physician in this country are generally illiterates and the ones who are literate can only understand Turkish texts” (Uzel, 2020). Moreover, there is little doubt as to why the surgical text books that he penned featured so many detailed illustrations. Although previous articles in clinical journals about Şereffeddin Sabuncuoğlu focused only on chapters from his book ‘Imperial Surgery’, this study, reports his whole life including his experiences and works within the historical and social context of his own environment.

METHODS, RESULTS & DISCUSSION

The Life story of Şereffeddin Sabuncuoğlu

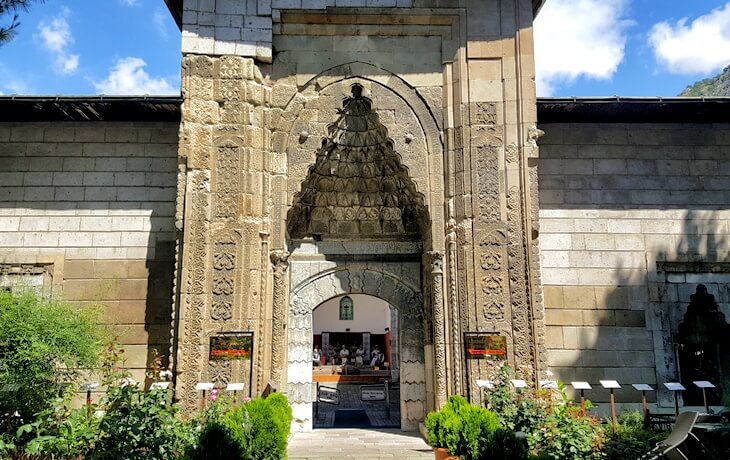

Based on what can be ascertained from his own writings, he spent all his life in Amasya where he wrote his manuscripts and treated his patients with the exceptions of his trip to Istanbul where he attempted to try to present his book to the Sultan as well as several journeys to Kastamonu, a nearby city where he sometimes treated patients (Uzel, 1992, 2020). Amasya is an ancient city located near the river “Yeşilirmak - Green river” with a long history dating back from 7500 BC and is well known for its royal tombs from the “Pontus Kingdom” (333-26 BC) that were carved in the rocks (UNESCO World heritage) (Wikipedia, 2021) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. A scene from the central Anatolian city Amasya.

His father’s name was Ali and his grandfather who was also a well known physician named Ilyas. Uzel (2020) has established that he came from a prominent local medical family and there is still an ancient neighborhood in Amasya, which was probably named after the family, “Sabuncuoğlu” according to local historians.

He was trained and later worked at Amasya Darüşşifa (Central State Hospital) built by the Mongolian Anatolian state Ilkhanate before the Ottomans in the year 1308 (Oguz, 2006, Uzel, 2020, Wikipedia 2021) (Figure 3A-B).

Figure 3A/B. Amasya Darüşşifa (Central State University Hospital), est. 1308. External/Internal (A/B) view respectively.

He was proud to mention in his books that he had been a member of the surgical staff for 14 years in that hospital, which in modern terms can be considered an equivalent of today’s State University hospitals that were funded by the Ottoman rulers, and were active till the 19th century (Uzel, 2020). Actually, only the most able could achieve those positions in the Ottoman health system and we can infer that those state positions were not life-long and there might be a retirement system based on the knowledge that even Sabuncuoğlu as a long lived brilliant physician and surgeon was only employed there for a limited time. Later in his 80s, it seemed that he mostly wanted to put his academic and practical experience into medical writing.

He reported that, one day, while he had been walking in the centre of Amasya, one of his former patients was standing in front of him pointing at his tracheostomy orifice treated by Sabuncuoğlu that undoubtedly saved his life and gave thanks to him (Uzel, 1992). This anecdote can be considered as a clear example that Şereffeddin Sabuncuoğlu lived and unassuming life among the public. On the other hand, another strikingly groundbreaking example of Anatolian medical practices that we learn from Sabuncuoğlu’s manuscripts is the existence of female surgeons referred to in his writing as “Tabiba” (Female doctor) (Uzel, 2020). (Figure 4).

Figure 4. A female physician (Tabiba) conducting a gynecological operation as the vaginal prolapsed excess mass, probably prolapsed myoma.

The principals of medical training and practice in early Ottoman period

Medical physicians were generally divided into two groups: the ones who had their own shops/premises and travelling ones. It has been reported that there were a thousand physicians practicing in 700 medical shops (surgeries) in private practice in Istanbul in the 16th Century. Medical training was classified into three consecutive phases; apprenticeship, journeyman and master degree. After being confirmed as a master, the trainee received his “certificate” which enabled him to perform medical procedures unaccompanied (Köken & Büken, 2018).

His handwritten manuscripts

There are three main books, among a total of seven, known to have been written by Şereffeddin Sabuncuoğlu. Akrabattin was the initial masterpiece that had been translated from a Persian manuscript related to the preparation of drugs, which he contributed several chapters towards in his mid 50s. The last one was Mücerrebname which was committed to paper at the ripe old age of 85 (Uzel, 2020). It is composed of various drug concoctions surprisingly closely related to modern medical multidisciplines. Additionally, this book is noteworthy in regard to current medical practice in that he mentioned about strategies to improve the composition and efficacy of certain medications and tested them on himself in an early form of modern phase I clinical trials; To test his newly formed antivenom, he let a poisonous snake bite him after taking the medicine before his assembled patients (Sabuncuoğlu, 1465; Uzel & Süveren, 2000; Uzel, 2020).

The previous book “Imperial Surgery” (Cerrahiyetü’l-Hanniye), which was originally published in duplicate form, is better known in contemporary medical literature circles and there are sample of historical clinical articles for almost all surgical disciplines based on the original one (Batirel, 1997; Darçin & Andaç, 2003; Doğan & Tutak, 2021a, 2021b, Er, 2013; Oguz, 2006; Sarban et al., 2005; Verit et al., 2003; Verit & Kafali, 2005). The book was rediscovered in the first quarter of the 20th Century by Süheyl Ünver and Ilter Uzel who compiled the original copies of the manuscripts into a book in the year 1992 and 2020 (Darçin, 2003; Oguz, 2006; Uzel, 1992, 2006, 2020). Today there are three original but slightly differing handwritten copies of “Imperial Surgery” surviving in Istanbul and Paris (Sabuncuoğlu, 1465, 1465; Uzel, 2020). Actually, this book is generally considered by Western historians as a Turkish replica of an Arabic book by Abul-Qasim Al-Zahrawi, At-Tasrif (On Surgery by Abulcasis) (936-1013AD) with some original contributions (Elcioglu et al., 2010). However, Uzel I (2020) opposed this point of view because he claimed that there was no known exact equivalent Arabic original of it. Nevertheless, even these contributions are important for that time when the evolution of medical science was so slow. However, the main differences between Cerrahiyetü’l-Hanniye and the others was that it was the first known illustrated surgical text book. Sabuncuoğlu had decorated his pages with miniature diagrams of almost all surgical applications in related sections unlike his inspiration, Abulcasis. In these colored pictures the author mostly drew himself as the main surgeon and featured patients positioned with the related devices and his surgical assistant if any (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Şereffeddin Sabuncuoğlu performing an abscess drainage in the axillary region. Notice the positions of both the patient and surgeon and also handled instrument.

Nevertheless, surely, “Imperial Surgery” by Sabuncuoğlu was the pioneer of the systematically designed surgical textbook (Uzel, 2020). The illustrations in this historical treasure composed of 138 unique surgical scenes and featured 168 different surgical instruments - 11 of which were of his own invention (Kadıoğlu et al., 2017; Uzel, 2020).

CONCLUSION

Şereffeddin Sabuncuoğlu as an ethical physician, surgeon, trainer, scientist and especially as the author of medical literature with his intricately beautiful diagrams and calligraphy should be ranked among the most prominent figures of the 15th Century especially when we consider his Western contemporaries who were just emerging from the Dark Ages. Although he was not a well-known clinician in his day, in modern times he has been gaining the reputation and recognition he deserves.