INTRODUCTION

Couchsurfing is, by far, the largest online hospitality service target and has become a popular traveling trend, and its development can be an interesting topic in the academic and tourism industry (Kuhzady et al. 2020;Medina-Hernandez et al. 2020;Sevisari and Reichenberger 2020). Couchsurfing typically involves improvised sleeping arrangements and temporary lodgment in other peoples’ private homes, thus, hosting information on hospitality accommodations, travel-related information, and knowledge exchange platforms are closely related to the development of Couchsurfing activities.

The purpose of the study is to analyze how community engagement affects Couchsurfers and hosts toward online communities based on the perspective of altruism and social identity. An online travel community facilitates the sharing of trip experiences, and tourists rely on such online communities to exchange information in a virtual environment. The gaps between the study with prior research, previous research that focused on social connections found that free accommodations might increase the numbers of tourists who will be Couchsurfing (Roberts 2020;O’Regan and Choe 2019). Studies have explored the role of Couchsurfing through the lens of their motivation (Eckhaus and Sheaffer 2019;Schuckert et al. 2018) and have explored the association between couchsurfers behavior and their connection to online travel communities (Schuckert et al. 2018;Shmidt 2020). However, driven by the online travel community, the study will examine how Couchsurfing communities and the benevolence of hosts affect the behavior of Couchsurfers. On the other, Couchsurfers are looking forward to hosts who are friendly and kind; prior research argued Couchsurfers rely on online communities to efficiently communicate with other members (Schuckert et al. 2018;Liu et al. 2016). Accordingly, considering participants of online travel communities as objects of trust from the perspective of altruism, we argue a person’s perception of the specific characteristics of other Couchsurfers may affect his/her trusting intentions and behaviors, and the study will explore the role of knowledge sharing among online travel communities which enhance to matching private accommodations with Couchsurfers.

Both Couchsurfers and hosts typically hope for mutual amiability. From the perspective of social identity theory, the benevolence of hosts plays a significant role for couchsurfers (Asri et al. 2020;Eckhaus and Sheaffer 2019). The Couchsurfers and the hosts have different characteristics that can be perceived in the information communication in the online community, and the importance of these information communication characteristics to both parties is also different in the real-world interaction (Decrop et al. 2018;Santos et al. 2020). Accordingly, the level of trust among Couchsurfers strongly affects the social interactions that unify and construct an online travel community. Previous research has found that Couchsurfers make trust decisions about their owners based on the number of positive recommendations, interactions within the community (Asri et al. 2020;Aydin and Duyan 2019), Couchsurfers who trust fellow members in the community instead of the host site through the online communities; and found that Couchsurfers experiences in hosting other members can positively impact their trust in the online travel community. Moreover, Couchsurfers tend to consistently trust host benevolence through knowledge exchanges that involve tacit knowledge (Chung 2017); knowledge sharing moderates trust and can affect the behavior of Couchsurfers.

The growth of online travel communities has allowed Couchsurfers to form personal connections with other individuals who share the same travel interests and enjoy the same activities. Indeed, online travel communities, such as www.couchsurfing.com, now have over 10 million members worldwide (https://about.couchsurfing.com/about/about-us/). A key function of online travel communities is the promotion of a form of generalized reciprocity, and these communities provide a knowledge platform that bridges Couchsurfers and hosts. In other words, although a couchsurfers stays with a host, the host does not expect anything in return from the couchsurfers.

Consequently, the concept of sharing exists in Couchsurfing, and travel knowledge is shared between the hosts and the Couchsurfers. Hosts usually have a magnanimous character that helps couchsurfers to achieve their travel goals. The study contributes to the relevant kinds of literature and theoretical perspectives by investigating Couchsurfers’ behavior intention, through empirical data collection from members of three well-known online travel communities who agreed to participate in the study. Our empirical findings also corroborate the trust of online communities in the theoretical model and highlight the importance of altruism in online travel communities.

This study proceeds as follows. Section 2 provides a literature review of relevant theoretical backgrounds and concepts and then develops our research model and hypotheses. Next, Section 3 describes research methods regarding data collection and measurement development. Section 4 presents the data analysis and research findings, and in Section 5, we discuss the results along with prior study findings and meanings. Lastly, in Section 6, we conclude this study with theoretical and practical implications, limitations, and future research directions.

1. THEORETICAL BACKGROUND AND MODEL

1.1. Altruism in tourism

Altruism is the principle or practice of caring for others (Saayman et al. 2020;Gu et al. 2019). It is also described as an expression of unconditional goodwill and not expecting others to return (Conte et al. 2019;Gimon and Leoneti 2020). People who emphasize the motivational aspect of altruism willfully benefit other people without the expectation of rewards (Silva et al. 2020;Bakshi et al. 2019). This characteristic empathizes with the needs of another person and is one explanation for why tourists share their travel information and comment on online travel communities.

Altruism can be divided into two orientations, namely reciprocal and true altruism orientations (Robitaille et al. 2021). Reciprocal altruism refers to mutually beneficial behaviors between two relationship participants in a symbiotic environment, in which there is an expectation of rewards. True altruism, on the other hand, is a selfless act that emphasizes the benevolence of others (Gandullia et al. 2021;Zhang and Li 2019) without the expected return while pursuing a purer and better life at the same time. In the field of tourism research, reciprocal altruism in altruistic behavior can be used to analyze the motives of altruistic behavior between Couchsurfers and hosts (Biraglia et al. 2018;Veiga et al. 2017), and true altruism has been conceptualized as an important motivated behavior factor of volunteer hosts (Cobo-Reyes et al. 2020).

Altruism is often used to discuss the field of volunteer tourism, knowledge-sharing behavior (Obrenovic et al. 2020;Sun et al. 2021), and well-being. From the perspective of altruism, thus helping tourists, making the host achieve a sense of satisfaction from the action (Zgolli and Zaiem 2018), and helping others regardless of whether anything is received in return. From the perspective of the interaction between hosts and Couchsurfers, altruistic tendencies indicate that the benevolence of hosts is based on a genuine concern for others. Accordingly, accommodation hosts kindly offer a chance for Couchsurfers to choose places for temporary accommodation.

From the perspective of Couchsurfing, in an online community with the same identity, members agree with the entire community because they have the same purpose (Roberts 2020;Schuckert et al. 2018). Altruistic behavior is an important facilitator of knowledge sharing intention. Members who exhibit altruistic behavior are usually more willing to share knowledge in online communities. In the other words, Couchsurfing can share their experiences regarding the accommodation in the online travel community, and they may recommend a good accommodation for other members to stay in.

1.2. Trust of online communities

Trust can be defined as the willingness to rely on another individual in whom one has confidence in (Zhang et al. 2020;Gruss et al. 2020); Trust is the belief that people are based on a set of beliefs that other people they depend on will act in a socially acceptable way by showing appropriate integrity, kindness, and ability (Gong et al. 2021); and it proposes that trust beliefs, including community engagement (Martinez-Lopez et al. 2017), integrity, and benevolence, (Zhou et al. 2020;Kanje et al. 2020) affect customers' behavioral intention. From a trusted perspective, hosts must also be able to identify potential threats and remain attentive to risks (Bowen and Bowen 2016). Prior research has also shown that online trust increases Couchsurfers’ desire to share travel information among the online community (Decrop et al. 2018). However, Couchsurfers who are more trusting and less cautious of others can be presented with many potentially rewarding opportunities. Therefore, trust among Couchsurfers tends to have important positive effects on the online communities that they belong to, especially in terms of communication and other forms of interaction.

Couchsurfing.com provides a platform for willing hosts to provide spare sofas in their homes for tourists who want to travel but cannot find a place to stay (Ronzhyn 2018;O'Regan and Choe 2019), and Couchsurfers will seek out the perceived value of their destination travel in the community (Aruan and Felicia 2019;Nusair 2020). Due to the development of the travel community, many well-known websites such as Backpacker and Lonely Planet also provide forums for tourists to share travel information with accommodation hosts (Chen et al. 2020;Sroypetch et al. 2018), the operation of the Couchsurfing.com service requires trust. Hosts let couchsurfers into their homes based on trust, so trust must be formed before the homeowner interacts with the Couchsurfing face-to-face.

Moreover, trust mediates the relationship between component attitudes and future intentions. Previous research has argued that understanding between couchsurfers and communities is improved by the prevalent trust of Couchsurfers in online travel communities and by the great similarities among community members (Schuckert et al. 2018;Chen 2018). Conversely, the community engagement of online travel communities shows another potential determinant: that is, online communities provide an environment that encourages mutual trust among Couchsurfers. Additionally, when Couchsurfers find that they have similar travel needs, experiences, or goals with other members, they may feel closer to one another, be more trusting, and be more willing to interact. Indeed, trust among Couchsurfers can be important in reducing uncertainty and minimizing the complexity of exchanges and relationships in virtual environments.

1.3. Social identity theory

Social identity theory focuses on the members’ perception of belonging to a specific social group, and the emotional and value meaning that group membership gives them (Plunkett et al. 2019;Miocevic and Mikulic 2021). Couchsurfers use online travel communities to search for accommodation; the knowledge online communities function as a catalyst to connect Couchsurfers and hosts (Xu et al. 2021). In addition, the social identity theory explains that members of the virtual community interact with the homeowner or other members in a certain way for their own goals and achieve the goal of travel by encouraging the sharing of knowledge between the homeowner and the members. Therefore, social trust has become an important link between the Couchsurfers and the host among the members of the virtual community.

Social identity theory has been applied to justify the activities of members in online communities, and it has been suggested that online communities influence member behavior through the mechanism of social identification. Previous studies have pointed out that when members of an online community believe that they belong to the same target group as other members, their willingness to participate will be formed in a purposeful relationship. In addition, the influence of community-specific knowledge and the participation of members emphasizes careful community design and thoughtful implementation of new features that may enhance enjoyment (McLeay et al. 2019;Zhang et al. 2020). The effect of online organizational rewards on enjoyment in helping others is contingent upon whether members are active or not, and enjoyment in helping others positively influenced members' attitudes toward knowledge sharing.

From the perspective of social identity theory, previous research argued that benevolence (Aljarah 2020;Jahanzeb et al. 2021), social trust (Zhou et al. 2021;Xin et al. 2016), and knowledge shared (Bedue and Fritzsche 2022;Jha and Jain 2020) determine how likely an online member is to identify with communities, which further influences his or her value for co-creation of activities in that community. Trust mediates the interaction of benevolence and authoritarianism by employing innovative behavior and knowledge sharing. Accordingly, we argue that benevolence acts as a predictor of online engagement, and convenience increases the faithfulness to an online community. The benevolence of hosts can help eliminate opportunistic behaviors and serves to decrease perceived risks associated with Couchsurfing relationships. Therefore, if Couchsurfers are interested in the benevolence of the host and are motivated to participate in online travel communities with the desire for social interaction, the number of members participating in Couchsurfing activities would increase.

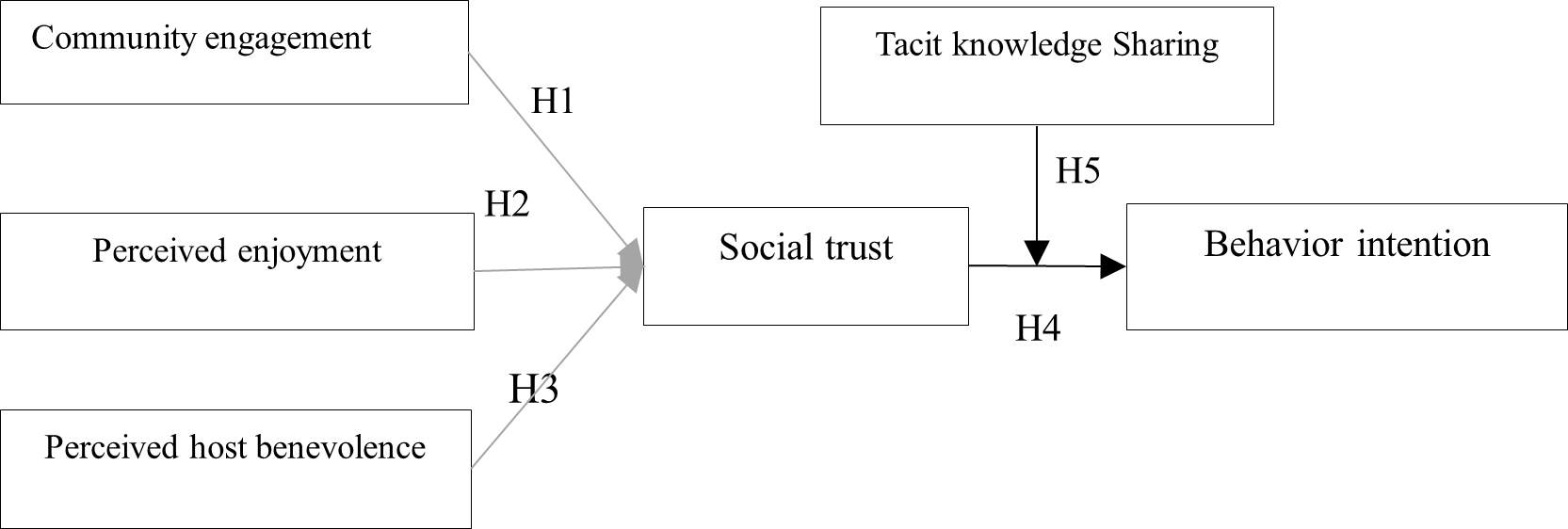

The reliance of Couchsurfers on the online community and their importance in making travel decisions are gaining increased attention. For this purpose, some preliminary theoretical work still provides us with insights into the relationship between the online community and Couchsurfers, research model was formulated from the perspective of altruism, trust, and social identity theory; as shown inFigure 1.

1.4. Community engagement

Community engagement refers to how simple, intuitive, and user-friendly a given website is perceived to be (Lichtarski and Piorkowska 2021). In the study, community engagement means that Couchsurfers receive great benefits from a travel community despite spending a brief amount of time browsing that website. Therefore, a convenient Couchsurfing website should feature user-friendly navigation and allow transactions to be completed quickly.

Previous studies have suggested that community engagement is positively associated with Couchsurfers’ evaluation of trust (Kanje et al. 2020;Sedera et al. 2019); community engagement has also shown a positive association with speed and exploration of website design. However, other researchers have argued that there are different, hidden subjective factors that affect Couchsurfing communities and the overall satisfaction of couchsurfers and that these factors are related to the process of use and system interaction of the communities.

Typically, online travel communities allow Couchsurfers to perform searches quickly and easily, and the connection between community engagement and trust has been well established. When Couchsurfers can share their travel experience and accommodation information through the exclusive travel website, they will be more willing to complete the Couchsurfing tourism goals through this community and recommend this community to others Couchsurfers.

1.5. Social trust

Social trust can be regarded as the average level of generalized trust of members in a community (Lee and Oh 2021;Qu and Yang 2015); it can also refer to the general belief that community members, community operations, or the community will not take action to take advantage of the weaknesses of others.

Social trust helps couchsurfers move out of committed relations with online travel communities (Ert and Fleischer 2019;Ert et al. 2016;Ezzaouia and Bulchand-Gidumal 2021). Social trust also emphasizes the universal propensity to trust others, and it can be an incentive factor for Couchsurfers’ travel behavior. Thus, it can also increase the communication and interaction between members because it decreases the possibility that other Couchsurfers will be opportunistic.

Trust facilitates the sharing of relevant travel information to other Couchsurfers in the online travel community; moreover, it involves the exchange of information about the emotional and positive impact of the Couchsurfers’ interaction with the community. When visiting an online travel community, Couchsurfers will be more likely to trust other couchsurfers whose profiles share detailed travel experiences and personal information. Moreover, Couchsurfers tend to pay more attention to comprehensive information. This leads to hypothesis 1:

H1: Community engagement is positively related to the formation of social trust.

1.6. Perceived enjoyment of online communities

Enjoyment is referred as the degree to which an activity confers pleasure and satisfaction to the individual who performs it and is independent of performance consequences (Oliveira et al. 2020;Han et al. 2021); the degree of perceived enjoyment's impact on the ease of use of the website occurs as members get a more direct experience of the virtual environment.

Previous studies on the influence of enjoyment on search behavior found that enjoyment of online communities will affect the behavior intention of participating in the community (Ku 2020;Assaker and O'Connor 2021;Slevitch et al. 2022;Liu et al. 2020. Indeed, enjoyment has been pointed to affect behavioral intentions among online communities’ interactions. For example, Couchsurfers’ perceived enjoyment can enhance perceived service satisfaction or trust.

In addition to the tool value of technology, the use of online travel communities for activities (such as Couchsurfers) is a pleasant exchange, which can increase tourists' search intentions for travel destinations. Moreover, online travel communities that provide enjoyment should positively affect the attention of Couchsurfers. Thus, we propose hypothesis 2 as follow:

H2: The level of perceived enjoyment of online communities is positively related to the social trust of their members.

1.7. Host benevolence

Benevolence is referred to as the degree to which the trusting party believes that another person wants to do good things instead of just exploiting others to maximize profits. In the virtual environment, kindness reflects the views of service providers on the discretion of others or charitable commitments (Khorakian et al. 2021;Dong et al. 2019). Previous research has argued that benevolence affects members’ behavior within online travel communities and has largely focused on the behaviors, usage continuously, and power relations associated with collaborative working with communities’ members (Okazaki et al. 2017;Cheng et al. 2019;Lee and Oh 2021). Couchsurfers face a significant challenge when it comes to creating a community of mutual trust that encourages their confidence in online communications. This increases the importance of sharing travel experiences and ensuring that profile information is presented in a visually pleasing way.

Indeed, the impressions that Couchsurfers have about the characteristics of other Couchsurfers in an online travel community can affect trusting intentions and behaviors. In the virtual environment, when the Couchsurfers are aware of the benevolence of the accommodation host, it is easy for Couchsurfers to choose this place to stay at as their home away from home. Couchsurfers perceptions of host willingness will encourage voluntary commitment to those Couchsurfers, and they may also be willing to have more interaction with the host. In addition, from the perspective of altruism, the character of benevolence from hosts will help Couchsurfers to choose their accommodation, and host benevolence could also lead to the development of greater trust in online travel communities. This leads to hypothesis 3:

H3: Host benevolence is positively related to the social trust for Couchsurfers.

1.8. Behavioral intentions

Behavioral intention is defined as the motivation and influence that drives the individual to perform a certain behavior (Zhou et al. 2020;Celik and Dedeoglu 2019). The online travel community that can attract and retain members is of great strategic value to the designers of the online community. Past research has found that online communities or vendors must instill important community commitments to their members to retain members.

When members trust an online community, they tend to exhibit a helping behavior and participate actively. Additionally, growing trust in electronic commerce has significantly increased the number of online searches related to Couchsurfing (Idemudia et al. 2018). Furthermore, trust in e-commerce and knowledge sharing played significant roles between Couchsurfers’ internet-based resources or decision making for destination choice.

Couchsurfers have a specific online search motivation and the motivation to search for information on that specific community. Previous research has further pointed out that trust will affect the behavior intention to join an online community (Kwon and Ahn 2021). Couchsurfers join the travel community to seek and meet their travel information and needs. Similarly, the ability of online communities to attract and maintain Couchsurfers has also caught the importance of hosts. In the context of a virtual environment, trust prolongs hosts’ selection of Couchsurfers. This leads to hypothesis 4:

H4: Social trust is positively related to the behavior intention of Couchsurfing.

1.9. Tacit knowledge sharing

Tacit knowledge is defined as the interactive behavior, experience sharing, thoughts, and participation between members in a specific community (Yeh and Ku 2019;Wang et al. 2015); in addition, tacit knowledge sharing is based on the mutual influence of distributive justice and procedural justice so that community members can commit to cooperation.

Many online communities of practice have provided online communities for members to create, collaborate, and contribute their expertise and knowledge (Yeh and Ku 2019;Nghiêm-Phú 2018). The online travel community is composed of self-selected groups of tourists. Because members have common interests or goals, they execute continuous intermediary interaction; the community's goals among members are governed by common norms and values, services provided to members, and common needs. In addition, the process of knowledge sharing of members will increase members’ trust and commitment to the online travel community.

Couchsurfers usually have the same experience in the online travel community, and they interact with computers based on common interests and values; among Couchsurfers and hosts, tacit knowledge sharing is also affected by the connections between communities and the trust among community members. Since the online travel community allows Couchsurfers to share ideas about travel and exchange views of the host, tacit knowledge and recommendations will help Couchsurfers to find unexpected and interesting travel information or make travel decisions. This leads to Hypothesis 5:

H5: Tacit knowledge sharing moderates the effect of trust on the behavior intention of Couchsurfing when selecting a host.

2. RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

2.1. Survey procedure and data collection

AsRonzhyn (2018) stated, to recruit participants, an invitation message was posted on the most popular location pages of three travel communities, namely Couchsurfing (https://www.couchsurfing.com/), backpackers (http://www.backpackers.com.tw/forum/), Couchsurfing (https://www.couchsurfing.com/), and Lonely Planet (http://www.lonelyplanet.com/north-america/forum); and check the participants who have members. Empirical data were collected by members from online travel communities; participants need to complete an online survey program that was developed using the SURVEYCAKE website (https://www.surveycake.com/) via invitation message; the invitation information stated the purpose of the study and provided a hyperlink to the digital survey form. We post invitation information, and 423 were returned completed from August of 2019 to May of 2020.Table 1 appeared the demographics of samples.

2.2. Metrics

This research first confirms the literature review related to the topic to confirm the external validity of our research model; we identified 26 potential research items for the questionnaire based on prior literature; besides, minor wording changes were made to render the questionnaire more relevant to the current study. Two tourism management professors refined and verified the translation accuracy of all survey items. All items were measured using a five-point Likert scale, whereby 1 indicated strong disagreement, 2 indicated partial disagreement, 3 indicated uncertainty, 4 indicated agreement, and 5 indicated strong agreement.

| Item and Reference | |

| Community Engagement (CE) was adopted fromLaroche et al. (2012) | |

| CE1 | I benefit from following the community’s rules. |

| CE2 | Participate in the community’s activities because I feel good afterward. |

| CE3 | Participate in the community's activities because I can support other members. |

| CE4 | Participate in the community's activities because I can reach personal goals |

| Perceived Enjoyment (PE) was adopted fromKu (2020) | |

| PE1 | I unconsciously browsed for a very long time when I visited the community. |

| PE2 | I enjoyed visiting the community. |

| PE3 | I feel the content of the community was exciting. |

| PE4 | I was pleased when I visited the website. |

| Benevolence (BEN) was adopted fromGefen and Straub (2004) | |

| BEN1 | I expect how hosts greet me. |

| BEN 2 | I expect that the host’s intentions are benevolent. |

| BEN 3 | I expect that hosts know what I need. |

| BEN 4 | I expect that hosts are well-meaning. |

| Social Trust (ST) was adopted fromLazzarini et al. (2008) | |

| ST1 | The hosts are trustful of couchsurfers. |

| ST2 | The hosts are trustworthy. |

| ST3 | The hosts are honest. |

| ST4 | The hosts are trustful to me. |

| ST5 | The hosts will respond in kind when other couchsurfers trust them. |

| ST6 | The hosts are good and kind. |

| Tacit Knowledge Sharing(TKS) was adopted fromYeh and Ku (2019) | |

| TKSE1 | I share my living experience with other couchsurfers. |

| TKSE2 | I share my expertise at the request of other couchsurfers. |

| TKSE3 | I share my ideas about travel with other couchsurfers. |

| TKSE4 | I talk about my tips on travel with other couchsurfers. |

| Behavioral Intention (BI)was adopted fromYeh and Ku (2019) | |

| BI1 | Select the host as a Couchsurfers accommodation in the future. |

| BI2 | Introduce the host for travel information in the future. |

| BI3 | Use the host as a Couchsurfers accommodation for sharing information. |

| BI4 | Select the host as a Couchsurfer’s accommodation as a channel for choosing a travel destination in the future. |

| BI5 | I am willing to recommend the host as a couchsurfers accommodation to my friends as a way of sharing travel information in the future. |

English version questionnaire translated into Chinese version for survey needs; from content validity perspective, three professors major in tourism management and information management were invited to verify and refine the survey items for translation accuracy into Chinese version. For the formal questionnaire to be suitable for the survey, the purpose of the pretest is to know whether the content of the questionnaire is clear and objective and whether it is suitable for the subjects to read. A pretest process of the survey in Chinese version questionnaire with 30 MBA students at the graduate institute of travel and tourism evaluating item sequence, their ease of understanding, and contextual relevance. The Cronbach α of the pretest is 0.912, the reliability of items is suitable for the survey (Sun et al. 2007).

3. ANALYSIS AND RESULTS

Recommendations include using structural equation modeling, sampling data, and re-estimating models to test the robustness of the norm and quantify when the sample size exceeds 200 (Doğan and Özdamar 2017;Ainur et al. 2017); In this study, LISREL 8.80 software was used to check the validity of each construct. First, Evaluate the convergent validity of this study by checking factor loading, composite reliability, Cronbach’s alpha, and extracted average variance (AVE) (Gefen et al. 2020;Kim and Frazier 1997).Tables 3 show the confirmatory factor analysis made to examine the convergent validity of each construct, and the statistics for factor loadings range was 0.59–0.94, and all AVE estimates were well above the cutoff value; therefore, it shows that all measurement scales have convergent validity.

Moreover, the results also show that the square root of all AVE estimates for each construct is greater than the correlation between constructs as shown inTable 3, which supports the discriminative validity of the research model. In addition, our tests have shown that all variance inflation factor (VIF) scores are below the recommended threshold of 10 (Naveed et al. 2021). Therefore, it is confirmed that there is no multicollinearity in the research model.

Notes:

a. The main diagonal shows the square root of the AVE (averaged variance extracted).

b. Significance at p <.05 level is shown in bold.

c. CE stands for community engagement, PE for perceived enjoyment, BEN for benevolence, ST for social general trust, TKS for tacit knowledge sharing, BI for behavioral intention.

The study aims to analyze how community engagement affects Couchsurfing and hosts toward online communities based on the perspective of altruism and social identity. After confirming the good reliability and validity for our research instrument, structural equation modeling was then performed to evaluate the hypothesized model presented by LISREL 8.80 software (Li et al. 2021b); The results show that the fit is good, and the data includes: X2/df = 2.3, GFI = 0.91, AGFI = 0.88, RMR = 0.054, RMSEA = 0.062, PNFI = 0.77, and PGFI = 0.68. Overall, the data showed a good fit with our hypothesized model. Besides, to estimate path coefficient significance, a bootstrapping technique was conducted to test the statistical significance of each path coefficient using t-tests, as shown inFigure 2 andTable 4. The results as follows.

First, all hypotheses are supported as expected. 40.5% of the variance of social trust can be explained by community engagement, perceived enjoyment, and perceived host benevolence, and 43,5% of the variance of behavior intention can be explained by social trust, tacit knowledge sharing, and the interaction term of social trust and tacit knowledge sharing.

Second, for all factors influencing social trust, we find community engagement has the greatest effect on it (β=0.79***). Next is perceived host benevolence (β=0.69***) and the last one is perceived enjoyment (β=0.38*). Besides, all factors influencing behavior intention, the interaction term of social trust and tacit knowledge sharing has the greatest effect on it (β=0.58**), and next is social trust (β=0.55**).

*p <0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001

4. DISCUSSIONS OF FINDINGS

4.1. The Trust Between Couchsurfers and Hosts in The Context of Travel Communities

In the study, community engagement is positively related to the formation of social trust (β=0.79***), and we also found that community engagement has the greatest effect on social trust. The findings which support the issues relating to travel communities provision relate to the hospitality authenticity provided, compared with prior studies (Ert and Fleischer 2019). When couchsurfers are more likely to use the community website to contact hosts and other members or tend to pay more attention to search relevant information, a higher degree of community engagement is thus created. Therefore, such a higher degree of community engagement will also then increase the degree of social trust toward such a community.

Next, the perceived benevolence of the host is positively related to the formation of social trust, and its influence of it on social trust is the second (β=0.69**). Consistent with the findings fromKhorakian et al.’s (2021) study, when couchsurfers perceived the higher degree of benevolence from some hosts, such as well-meanings or knowing what couchsurfers want, and such information shared in the online travel community will then facilitate mutual trust and enhance couchsurfers’ confidence in online communication, thereby forming higher degree of social trust then.

In addition, perceived enjoyment perceived from the online travel community is also positively related to the formation of social trust (β=0.38*). As stated bySlevitch et al. (2022) andLiu et al. (2021), when couchsurfers perceive a higher degree of enjoyment provided by the online travel community, they might unconsciously browse the contents or information for a long time and felt exciting or pleased. As such, their search intentions and social trust will then be enhanced.

4.2. Behavior Intention to Use Travel Communities

Social trust is positively related to the behavior intention of couchsurfers (β=0.55**) and our findings are also consistent with the results of prior studies (e.g.,Okazaki et al. 2017;Cheng et al. 2019;Lee and Oh 2021). From the perspective of trust, hosts and couch classes must also be able to identify and build mutual trust, reducing potential threats and risks; moreover, the operator of the online community can use this mechanism to strengthen the trustworthiness and benevolent characteristics of the host and to help couchsurfers to complete a pleasant journey. As such, the higher degree of social trust perceived by couchsurfers will then enhance the higher degree of their behavior intention to select some hosts as accommodation, share or recommend them in the future.

4.3. Tract Knowledge Sharing Moderates the Relationship Between Trust andBehavior Intention of Couchsurfers

In addition, tacit knowledge sharing moderates the effect of trust on the behavior intention of couchsurfers when selecting a host, as supported in the study with (β=0.58**). Couchsurfers usually share their travel experiences in online communities with people who have a website account when they trust that the related website would not reveal their personal information. Accordingly, aggregating and transforming tacit knowledge into useful tourism information can benefit both the communities and the couchsurfers. As such, when they felt they can share a higher degree of their tacit knowledge (e.g., living experience, expertise, ideas, or tips) with other couchsurfers in the online travel community, the effect of social trust on Couchsurfers’ behavioral intention will be greatly enhanced.

IMPLICATIONS AND CONCLUSIONS

This study integrates altruism, trust, and social identity in the field of online communities, and it expands altruism research on tourists’ behavior; this study analyzes how community engagement affects Couchsurfing and hosts toward online communities based on the perspective of altruism and social identity. Specifically, the prevailing relationship marketing approach suggests that trust and flow experience should play a critical role, however, some previous empirical results have provided support for the dominance of altruism (Li et al. 2021a). Altruism shows the goodwill of the hosts to show sincere care for Couchsurfing, the importance of benevolence, and trust as indicators among community members; community engagement prompts the formation of social trust among Couchsurfing and hosts toward online communities, and benevolence is positively related to the formation of social trust. Therefore, trust has become an important link between Couchsurfers and the host among members of the online travel community, these indicators can be used to evaluate the factors that influence the behavioral intentions of couchsurfers.

As such, this study proposed that (1) community engagement, perceived enjoyment, and perceived host benevolence positively influence social trust, (2) social trust positively influence behavioral intention, and (3) tacit knowledge sharing moderates the relationship between social trust and behavioral intention, and these findings are supported from our analysis and could provide relevant insights for the management.

First, community engagement, perceived enjoyment, and perceived host benevolence positively influence social trust, and the greatest effect is made by community engagement. Likewise, community engagement is an enzyme catalyst between couchsurfers and online travel communities.

To increase Couchsurfers’ higher degree of community engagement, managers of online travel communities should provide valuable benefits or activities to encourage users to search, browse, or interact with others for a longer time in the places, thereby generating their higher degree of social trust as well. For example, in addition, to providing a user-friendly interface for information search or an interesting environment for users, managers of online travel communities can also post some recent and heated discussion topics to encourage user participation and interaction. After that, managers of online travel communities can also summarize the rankings of best places, relevant hosts’ information for couchsurfers and facilitate their social trust. Moreover, managers can also provide the incentive to encourage couchsurfers to spend more time browsing content or willing to take their time to plan their trip using that certain community.

Second, perceived host benevolence positively influences social trust and its influence on social trust is in the second. Likewise, to let more couchsurfers know there are still lots of hosts who want to do good things instead of just exploiting others to maximize profits is very important. As such, we suggest that managers of online travel communities could encourage more potential hosts to join their communities. Besides, they can establish a systematic evaluation mechanism on platforms and provide greater choices to couchsurfers, thereby enhancing users’ greater social trust toward online travel communities.

Third, perceived enjoyment also has a positive effect on the formation of social trust. In other words, websites that provide an enjoyable experience could increase the level of satisfaction among couchsurfers, which in turn, could encourage them to visit the website multiple times. In addition to providing more pleasant content and a well-designed website interface, to have some exciting interactive online games or periodic activities with awards which to please and facilitate more users to interact jointly is also a good strategy for managers of online travel communities. In summary, through the strategic planning and execution for providing a higher degree of community engagement, perceived enjoyment, and perceived host benevolence, the higher degree of social trust can be then created, and the higher degree of behavioral intention can also then be facilitated.

Lastly, as indicated in the findings, tacit knowledge sharing significantly moderate the relationship between social trust and behavioral intention. Likewise, how to encourage users to share more useful tacit knowledge is also of its importance. In order to do so, that gamification mechanism is a very useful strategy for managers of online travel communities is recommended. For example, when couchsurfers actively share their useful living experience, ideas, or tips about some specific travels, they can obtain some reward points or coupons, and these points or coupons can be used for goods or service purchases in some e-commerce platforms cooperated with online travel communities. Consequently, when different users continuously contribute lots amount and valuable tacit knowledge in travel communities for various travel experiences or contents, some higher degree of tacit knowledge sharing can significantly magnify the relationship between social trust and user’s behavioral intention, thereby generating sustained competitive advantages for online travel communities.

Limitations and future research

We acknowledged that some research limitations exist in this study. However, some of these might provide future study directions. For example, we present our findings with whole sample data, despite our study did provide the relative importance of constructs for Couchsurfing success. However, future research is suggested to investigate the group difference and results for our research model, such as different gender, occupations, cultures, or travel motivations. This may thus provide more marketing insights and strategic suggestions for Couchsurfers or hosts to choose or provide services.

Next, Couchsurfing, by far, not only has become a popular traveling trend but also become the largest online hospitality service target as well. How to develop strong emotional connections between Couchsurfers and hosts in online communities becomes a very critical issue already. Likewise, in addition, to investigate factors influencing Couchsurfer’s intention, the reasons why hots are willing to provide accommodation services through the different theoretical lenses are of quite an importance for future studies.