INTRODUCTION

Universities are key institutional players within their localities since they have been shown to have significant economic and social impacts on their communities1. In the 21st century, universities are changing and trying to be closer to their communities and the social problems they have. This, among other, entails introducing new skills in their students, which would make them more competitive in the ever-changing labor market. A number of studies demonstrated the need for experiential learning2-6 as university graduates are not sufficiently prepared for entering the labor market7 and due to a lack of provision of appropriate skills by university programs, there is a decreased employability of graduates8. This is why an increase of businesses working with schools has been noted9 as also employers require readiness of workforce10, alongside willingness of graduates for work-related experience11 as to increase their own competitiveness and assign a meaning to the taught theoretical classes. Experiential learning may be performed in many forms, e.g. internships, classes in cooperation with businesses, simulation of projects, study abroad, etc., which Kuh12 termed as high-impact practices. This also entails service learning as participating in voluntary programs, working in social enterprises or civil society organizations. Service learning is a learning methodology which addresses real community issues and problems13. It puts together both learning as well as social objectives, thus improving the quality of education as well as increasing employability of graduates14. As a specific experiential learning form, service learning has demonstrated to increase students’ problem-solving abilities but also has a positive impact on their communication skills15,16. It furthers the students’ ability for transferring abstract concepts into practical activities17, enhances their entrepreneurship, leadership and team skills, feelings about self18, improves critical and creative thinking19, their presentation skills and decision-making20. Most importantly, it increases the likelihood of graduates’ employment by as high as 30 %17. On the other hand, although globally, the introduction of social entrepreneurship courses is on the rise21, there is still a relatively low number of service learning dedicated courses offered, which was evidenced in Croatia (three dedicated courses and 25 of them applying service learning principles). When we look at the definitional features of social entrepreneurship the main goal of the endeavor of social entrepreneurship is to create a positive social impact. The key difference between entrepreneurship in the traditional sector and social entrepreneurship is that the latter prioritizes welfare and social goals. So traditional entrepreneurship is primarily undertaking entrepreneurial activities to make a profit for its owners or stakeholders. On the other hand, social entrepreneurship is undertaking entrepreneurial activities as means to achieve some social goals. Thus, social enterprises have the focus on social mission but also have financial goals, so it could be said that social entrepreneurs expect double return, both economic and social22-24. Service learning entails an experiential approach to education based on mutual learning25, thus being complementary with social entrepreneurship. Connections between concepts are noticed by different authors26-30, such as collaborative relationships, orientations towards community, local embeddedness and experiential learning. Service learning could be a good interdisciplinary approach to teach social entrepreneurship as a connecting theory; practice and real-life social problems can foster the development of competencies of future social entrepreneurs. Brock and Steiner’s analysis31 showed that a number of educational institutions teaching social entrepreneurship are assigning service/experiential learning projects to give students hands-on experience. Some experiences state that service learning and social entrepreneurship can co-exist on college and university campuses with little or no collaboration or communication between the two programs27. The same authors also note that they have several qualities they share so could not only work together but could benefit from one another’s strengths. McCrea4, on the other hand, finds that service learning nature is perceived by faculty members as irrelevant for entrepreneurship. Further on, business education is usually perceived as entailing overly profit-oriented approach without moral values32 so matching it with service learning may complement for those deficiencies by introducing the concept of social responsibility. Moreover, Mueller, Brahm and Neck26 suggest that service learning is one of the best learning approaches to social entrepreneurship education. Interestingly, it also offers students an opportunity to tackle problems which really matter to them while business education often deals with problems which are too specific and difficult to understand for inexperienced students. Although widely applicable, service learning usually finds a strong spillover in the social entrepreneurship. Geographical context shows that social entrepreneurship has been developing in Europe for the last few decades33. The big push for institutional recognition of social entrepreneurship on the EU level was Social Business Initiative34. Currently, Social Economy Action Plan35 is oriented towards creating the conditions and opening opportunities as well as a wider recognition of social economy and social entrepreneurship. In Croatian terms, development of social entrepreneurship is a relatively new phenomenon, although social economy has a distinctive history. The promotion of social entrepreneurial activity in Croatia began approximately 15-20 years ago, mainly through foreign organizations36,37 while its institutional recognition came with the Strategy for development of social entrepreneurship 2015-202038. The number of social enterprises in Europe varies from country to country, with Italy (102 461), France (cca. 96 603) and Germany (77 459) being the leading ones21. Although the data provided are not completely reliable and sometimes hardly comparable as social entrepreneurship is still not sufficiently regulated and therefore under-researched, according to the existing report in the European context21, Croatia ranks rather modestly (526 social enterprises in 2018). Comparing it with other ex-Yugoslav countries with available data, it ranks lower than Slovenia (1393) and Northern Macedonia (551) but higher than Serbia (411) and Montenegro (150)21. It may well be that the number of social enterprises in Croatia differs from the Borzaga et al. report21, which may be detected only after a thorough mapping exercise. Other estimates range from around 10039 to around 30033 social enterprises in Croatia. When it comes to legal types of social enterprises in Croatia, they may be divided in the following groups: • social entrepreneurship associations registered for economic activities; • social cooperatives; • veterans social-working cooperatives; • cooperatives pursuing social aims; • foundations registered for general interest and economic activities; • companies founded by associations; • institutions founded by associations; • other companies pursuing explicit social aims and operating as not-for-profits; • sheltered workshops40. Vidović and Baturina’s analysis33, in trying to assess types of social enterprises in Croatia, suggest three types: social enterprises driven by employment purposes, social enterprises driven by financial-sustainability goals and social enterprises driven by the search for innovative solutions. Looking at the status of social entrepreneurship, the recent analysis34,40 recognizes the lack of visibility and recognition of social entrepreneurship in Croatia. Other research also notes that social entrepreneurship is not recognized among citizens41. Service learning in Croatia, as well as globally, is mostly implemented within the university educational curricula. It is still underrepresented in academic curricula42, mostly offered as an elective course, and is currently conducted at humanities-oriented faculties. For the first time, service learning entered the educational system in Croatia in 2006 at the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences (course: Service Learning) in Zagreb, as part of the graduate study of Information and Communication Sciences. It is also carried out at the University of Split – Faculty of Economics (course: Professional Practice – Service Learning) and at the University of Zagreb – Social Work Study Centre at the Faculty of Law (course: Service Learning and Social Interventions). The concept of service learning, however has also been introduced within other courses at different faculties where it is used as a pedagogic tool for promoting community development. The faculties closely cooperate with other educational institutions, associations and civil society organizations (CSOs)43. But, the experiences from service learning implementation as a specific course at the University of Rijeka suggest challenges in the implementation itself, such as the integration of the course content and community activities, and the lack of university support44. Research45 shows that students were willing to consider and showed a substantial interest in enrolling in an elective course with a component of service learning. Teachers in Croatia are generally interested in the possibility of engaging in service-learning46. On the other hand, students have generally not heard of the service learning method and have no experience with it, but express a desire to enroll in such a course and using the service learning method47. Although the service learning topic at Croatian universities is not a novel concept (first introduced in 2006), it still has not succeeded to gain a greater attention in a wider society. One would expect that this type of learning offers students greater opportunities at the labor market as it provides them with hands-on experiences and practice-oriented learning. However, it seems that this is not the case as Croatia still has a high rate of youth unemployment, which makes up 27 % (or 33 090 persons) of the entire registered unemployment (123 445)48. Within the EU context, in 2021, Croatia was ranked 9 for its overall unemployment rate (7,4 %) and its youth unemployment rate is also among the highest ones49. When looking at the specifically vulnerable neither in employment nor in education and training population (NEET), Croatia’s NEET unemployment rate has been consistently above EU average since 201150. Besides, relevant analysis51 notes that there is a general problem of lack of care of society and politics about young people in Croatia. This fact was a leading motivation for this study and its importance is seen in a direct contribution to solving the youth unemployment problem. It was assumed that both formal and informal service learning programs offer skills young people lack when entering the labor market when compared to other theory-based educational curricula. In this way, they should be more competitive in getting a job or more prepared for self-employment. This is why we conducted a study with the aim to explore the connection between service learning and youth employment in social enterprises in Croatia, as it was assumed that social enterprises were more acquainted with the service learning concept valuing the skills such educational programs offer to young people. The goal of the research was to assess the possibilities of service learning in the Croatian social entrepreneurship ecosystem and what is its potential for contributing to youth employment. Therefore, the main research question was the following: does service learning influences youth employment in Croatia, and if so, how? Therefore, the purpose of the work was to strengthen the links between service learning and youth employment in (social) enterprises. Based on the research results, some recommendations are put forward, which may serve in strengthening this link and eventually enhance youth employment. Therefore, significance of the study is seen in giving input into potential decrease of youth unemployment rate, development of service learning and social entrepreneurship in Croatian context. The structure of the article is as follows: after this Introduction, methodology of the research is explained in the section Materials and Methods, followed by the Results of the research. Finally, the Discussion offers interpretation of the research results putting it in the context with the existing theory and offering recommendations for the increase of youth employment in Croatia, especially in social enterprises with service learning being a “helping hand” in that respect.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In order to investigate connections between service learning and youth employment in social enterprises in Croatia, two separate surveys have been designed, the first one covering the topic of service learning and the other one social entrepreneurship and youth. Each survey consisted of ten multiple choice questions, some of them offering a possibility for a larger selection of possible answers, while the others were yes-no questions. Some multiple-choice questions allowed only one answer as to detect the key answers while two of them allowed for several answers. Data collected in both surveys were statistically analyzed using MS Excel. The survey has been conducted within the European Social Fund supported project “Using Dialogue for the Croatian Network for Social Entrepreneurship” from February to August 2021. The research sample covered 291 participants from different existing social enterprises in Croatia, new social entrepreneurs (legal subjects planning to start or to change their business principles harmonizing them with social entrepreneurship), project partners’ employees and stakeholder1, different veterans social-working cooperatives, and young people who had participated in both surveys. This constitutes a part of the wider ecosystem of social enterprises and their supporters in Croatia. The survey on service learning focused on the topics of the participants’ awareness of the service learning concept; their knowledge about the existence of service learning study programs in Croatia; their own educational background in service learning, formal or informal; the need for formal or informal service learning study programs; the need of formal education in service learning in the selection of job candidates; on the job training; the relationship between service learning and social innovations; and the detected lack of key knowledge/skills among young employees in social enterprises. In the survey on youth employment in social enterprises, the questions covered the number of young people employed in social enterprises; their reasons for seeking jobs in social enterprises; utilization of youth employment policy measures by the employers; (dis)advantages for employing young people in social enterprises; youth recruitment for job openings; length of youth employment in social enterprises alongside durability and security od employment in social enterprises; key incentives for youth employment/willingness to keep jobs in social enterprises; and biggest advantages social enterprises can offer young people. Research respected ethical principles in quantitative research. Respondents were honestly familiarized with the goals of the study and gave informed consent to participate in the study. The anonymity of respondents was ensured as the survey did not ask personal data or had questions that would reveal respondents’ identities. The obtained data was stored appropriately and only project leaders and researchers doing analysis had access to the data.

RESULTS

Results of the study are first presented as separate findings of the two surveys, the first one focusing on the topic of service learning and the other one on social entrepreneurship and youth. Further on, they are cross-fertilized as to find possible relations between the topics.

SERVICE LEARNING

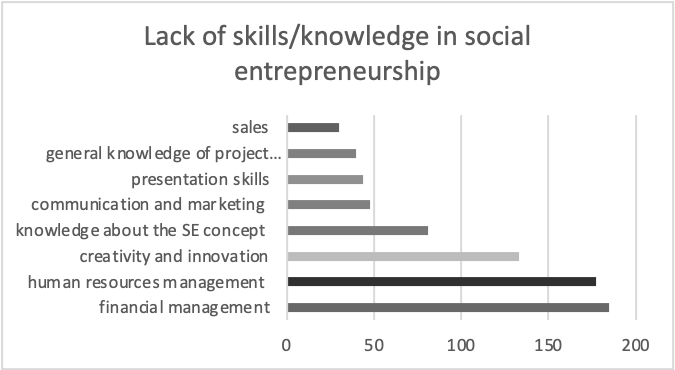

When asked if they are familiar with the term ‘service learning’, 289 (99,3 %) out of 291 participants answer affirmatively, whereas 285 (97,9 %) respondents are aware of the existence of studies related to service learning in Croatia. None of the participants have attended any course or study related to service learning during their formal education or any informal service learning course. Participants believe that the existence of formal service learning educational programs are necessary for becoming a social entrepreneur (286 or 98,2 %), but also agree that informal service learning course may substitute for formal education (289 or 99,3 %). The vast majority of participants say that upon recruitment they do not select candidates who have taken a service learning course within their formal education (284 or 97,5 %), and all participants believe that it is possible to educate candidates through work. This proves the prevalence of on the job training over formal service learning study programs. Also, all participants agree that service learning influences the development of innovations in social entrepreneurship in Croatia. The key skills or knowledge that employees in social entrepreneurship lack is ranked as follows: financial management (n = 185), human resources management (n = 177), creativity and innovation (n = 133), knowledge about the very concept of social entrepreneurship (n = 81), communication and marketing (n = 48), presentation skills (n = 44), general knowledge of project management (n = 40) and sales (n = 30), see Figure 1.

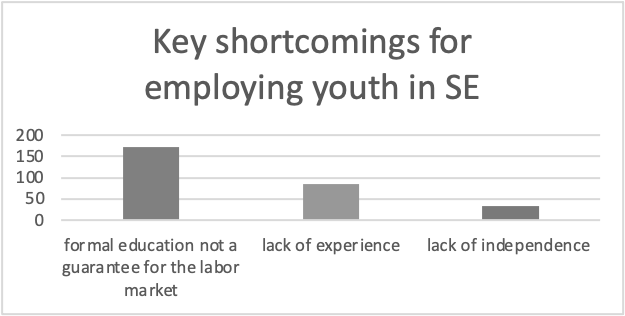

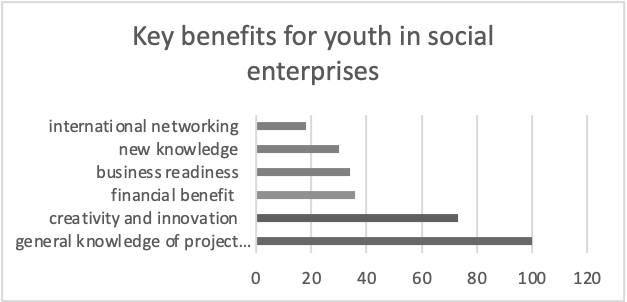

SOCIAL ENTREPRENEURSHIP AND YOUTHAs for the number of young people employed in their social enterprise, participants mainly answer that the number varies between 5-7 (40,89 %) and 3-5 young persons (27,84 %). When they are looking for new employees, the vast majority of participants recruit young people from the Croatian employment service (92,78 %) and 95,88 % of them say that they are benefitting from some of the public policy measures to employ young people. 92,44 % of respondents think that social enterprises offer young people permanent and secure employment, while young people mostly stay 2-3 years (39,86 %) or 1-2 years (36,77 %) in the participants’ enterprises. Participants believe that the key incentives for encouraging the employment of young social entrepreneurs or for their stay in the social entrepreneurship sector can be the general climate that encourages the development of social entrepreneurship (48,45 %), financial incentives (24,74 %) and education on social entrepreneurship in existing educational institutions (19,24 %). According to the participants, the primary reasons why young people choose to become social entrepreneurs are their social awareness (54,64 %), the fact that they need employment (15,46 %) or their willingness to help others (12,03 %). A key advantage of employing young people in social enterprises over employing people of another age group is seen in the fact that they quickly respond to social changes/trends (59,11 %) and have specific knowledge that older employees do not have (14,43 %). On the other hand, its shortcomings are the fact that formal education does not guarantee their readiness for the labor market (n = 173 or 59,45 %), a lack of experience (n = 85 or 29,21 %) and a lack of independence at work (n = 33 or 11,34 %), see Figure 2. Participants reckon that the main benefits that young people can gain from working in their enterprises are a general knowledge of project management (34,36 %), creativity and innovation (25,09 %), financial benefit (12,37 %) and business readiness that they would not get in ‘classic’ enterprises (11,68 %), see Figure 3.

RELATIONS BETWEEN SERVICE LEARNING AND YOUTH IN SOCIAL ENTREPRENEURSHIPEstablishing relations between the answers to both surveys allowed us a further exploration, which detected some overlaps but also inconsistencies in participants’ opinions and actions. Thus, project management (13,75 %) was detected as one of the areas in which employees in social entrepreneurship lack general knowledge (service learning survey) for which working in social enterprises easily compensates (social entrepreneurship and youth survey) since it is detected as one of the main benefits that young people can gain (34,36 %). Thus, on the job training seems to complement this educational shortage. While education on social entrepreneurship in existing educational institutions (19,24 %) is seen as one of the key incentives for encouraging the employment of aspiring young social entrepreneurs and for fostering their stay in the social entrepreneurship sector, majority of participants (59,45 %) think that one of the shortcomings of employing young people in social enterprises is the fact that formal education does not guarantee their readiness for the labor market. This also relates to the opinion all of the participants (291) who agree that it is possible to educate candidates through work, firmly confirming doubts related to the curricula taught at the existing study programs. This raises questions why employers do not select candidates who have taken a course in service learning (97,5 %), which may potentially compensate for that. The reason behind it is unknown, though. The fact that none of the participants, who are also social entrepreneurs, have attended any course or study related to service learning but that they believe it to be essential for becoming a social entrepreneur (98,2 %) is possibly tied to their own past education through work which lacked service learning courses. Their belief that education is essential for working in service learning may still suggest that education would make it easier for young people to become social entrepreneurs. All participants of the service learning survey acknowledge that service learning impacts the development of innovations in social entrepreneurship in Croatia, but at the same time part of them (45,70 %) perceive creativity and innovation as one of the key skills that employees in social enterprises lack. Equally, participants of the social entrepreneurship and youth survey believe that one of the main advantages of working in social enterprises for young people is the development of creativity and innovation (25,09 %). This may mean that on the job training again complements the shortages in study programs. Further on, such assertions raise questions about whether all social enterprises offer this sort of opportunities and how often. In the same way, the question of whether social enterprises that bring benefits of developing creativity and innovation are only individual cases and the question of to what extent do service learning study programs introduce these skills, remain to be further explored. These inconsistencies lead to a conclusion that although employers in social entrepreneurship are highly aware of the existence of study programs related to service learning, they still lack a profound knowledge on them as they do not employ service learning graduates. Further inconsistencies in answers concern the social entrepreneurship and youth survey in which respondents agree that social enterprises offer young people permanent and secure employment (92,44 %), what is not reflected in the statements that young people mostly stay only 2-3 years (39,86 %) or 1-2 years (36,77 %) in their enterprises. It remains unclear whether young people continue to work in other social enterprises or seek and find employment elsewhere.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUDING REMARKS

This research connects three relevant topics in Croatia, service learning, social entrepreneurship and youth. The research showed that almost all respondents are familiar with the term service-learning and agree that these courses can be useful. That is similar to the experience of other research conducted in Croatia45,46. The total absence of attendance of any course or study related to service learning during the formal education detected in this research may not be surprising as most of the respondents attended higher education in the years before the introduction of service learning in the Croatian higher education system. Previous research in Croatia45 states that students who previously heard about this teaching method and those who have experience of volunteering are more interested in enrolling in an elective course with a service learning component. Therefore, service learning is considered highly useful as it enables knowledge and skills for easier integration on the labor market. Service learning perspective is very close to the third mission of the university i.e. economic and social mission and its contribution to communities and territories. Croatia still faces significant challenges in creating an enabling environment for the integration of the third mission into universities. Research52 shows that the connection of teaching and community engagement, as per service learning methodology defined by Dixon13, is absent which could also be an obstacle for service learning development. The fact that almost a third of the respondents in the research asses that employees’ in social enterprises lack knowledge about the very concept of social entrepreneurship is worrying but also suggest that this field is not sufficiently developed in Croatia. Underdevelopment of the field is recognized in recent analysis40. The first Strategy of development of social entrepreneurship in Croatia38 put forward increasing visibility and clarifying legal and policy status of social entrepreneurship as one of its major goals but the evaluations of the Strategy showed that those goals were not achieved53. This points to the greater need for promotion, visibility and understanding of the social entrepreneurship concept among entrepreneurs as well as citizens. The fact that participants consider that the general climate should be the key incentive for encouraging the employment of young social entrepreneurs or for their stay in the social entrepreneurship sector is in line with another analysis, which assessed it as a relatively unfavorable with the lack of political will to prioritize the development of this sector40,54. While other incentives are also important (e.g. financial support, education), the general climate has the greatest impact on the young people’s employment in social enterprises. Clear strategic framework fostering youth employment and social entrepreneurship development is, therefore needed. Key skills or knowledge that employees in social entrepreneurship lack, per research respondents, are mostly related to financial and human resources management. This corresponds with the early development phase of the social entrepreneurship in Croatia in which key business skills are still missing within a sector40. Participants in the research state that service learning influences the development of innovations in social entrepreneurship in Croatia. This contradicts McCrea’s4 findings on the perception by faculty members of the irrelevant nature of service learning for entrepreneurs. Also, it can be interpreted as one of the possible ways to overcome the lack of creativity and innovation by employees in social entrepreneurship that respondents also recognize. A relatively small number of young people employed in social enterprises detected in this research is aligned with the previous study suggesting that the number of persons employed in social enterprises in Croatia is usually small39. This points to the conclusion that service learning may be beneficial for developing creative skills and innovation but is still not sufficient for mastering key business skills. Eventually, it also results in a small number of young people employed. When employing young people, most of the respondents use the usual recruitment channels such as the Croatian employment services and active labor market policies. This result does not surprise as these are the main channels for employment in Croatia. However, recent research55,56 states that young people and experts recognized different limitations in the work of the Croatian employment services and their cooperation with different stakeholders. Along the same line, active labor market policies in Croatia are only partly efficient and appropriately targeted57,58. Still, the existing public policy measures for employing young people are benefitted from. Also, it should be noted that active labor market policies do not have tailored measures for employment in social enterprises, however social enterprises can use available measures as any other enterprise. In this sense, proactive recruitment past the usual recruitment channels is advocated (e.g. at educational institutions, volunteering organizations). Likewise, labor market policies would benefit from revisions, involving also social entrepreneurship. The research results show that social enterprises, although ideologically attractive, do not offer stable and secure employment for young people. This is in line with the research done by Šimleša et al.39, which demonstrated that most of the social enterprises in Croatia were operating only a few years. Also, recent European social fund tenders for the development of entrepreneurship contribute to the development of new social enterprises in Croatia. These facts suggest that it is likely that in most social enterprises in Croatia young people cannot find stable jobs. This calls for further research which should detect the reasons behind inability of social enterprises in Croatia to remain operational. Further on, formal education does not guarantee the graduates’ readiness for the labor market and a lack of experience is seen as an obstacle for their integration on the labor market. This is in line with another research55 which shows that young people estimate the education system as offering them outdated knowledge and methods of work, connected to the lack of their practical skills and experiences. Likewise, it also corresponds with research studies2-6, which detected the need for experiential learning. Further on, it goes in hand with Polk-Lepson Research Group’s results7 which showed insufficient preparedness of university graduates for entering the labor market. Changes in the Croatian education system are necessary, which could tackle the incompatibility of educational programs with the labor market and an increased need for practice. This has been noted both by researchers59 and the public. Education on social entrepreneurship in existing educational institutions can be, per our respondents, one of the incentives for encouraging the employment of young social entrepreneurs. However, social entrepreneurship is only marginally represented in the educational system although there are some positive developments like the new courses and educational programs40. Toplek60, further on, detected that higher educational institutions are increasingly recognizing the importance of social entrepreneurship and the benefits that come with introducing such subjects into the teaching content. So continuing with this practice, especially in the form of service learning can create better readiness for the labor market of young people (for working in social enterprises and on other jobs) coming from the higher education system. According to the participants, the primary reason why young people choose to become social entrepreneurs is their social awareness. This is similar to the theoretical social motivation connected to social entrepreneurship. Some authors even go further, and given the motivation to help others and the community, describe characteristics of social entrepreneurs idealistically61,62. Bull and Ridley-Duff63also discuss ethics and positive ethical connotations connected with social enterprises. Similarly, research on the third sector in Croatia64 states the prevalence of prosocial motivation in the third sector of human resources. The social awareness, therefore exists, both in the private sector as well as in the CSOs. Bigger prevalence of service learning programs connected to the development of social enterprises, or students contributing to social enterprises in the framework of the service learning courses can be close to the “critical” approach to service learning65 with an explicit social justice aim or even close to the concept of the transformational learning66. Although service learning can have positive outcomes on students in different ways, we can also asses it critically and note limits of service learning in higher education (pedagogical, political and institutional)67. This may especially be relevant for the Croatian context in which (very) gradual transformation of the education system is noted68, with a lack of entrepreneurial spirit in the universities. However, Croatian HEIs have been modestly improving their capacity to collaborate with external stakeholders to exchange knowledge and promote innovation69 which opens space for the development of service learning and social entrepreneurship. The idea of service learning is gaining rising support. Although already at the beginning of the century the questions about the institutionalization of service learning were raised70, some authors recognize that service learning is rarely “hard-wired” into institutional practices and policies67. This is also the case in Croatia. There is a growing interest which can be witnessed by the successful implementation of the service learning projects in cooperation of universities and civil society organizations or the development of service learning centers or offices (e.g. at the University of Split – Faculty of Economics and the University of Zagreb) but with recognized challenges in implementation and lack of support44. This article highlights the additional need for further development of service learning courses connected with social entrepreneurship, which could contribute to the employment of young persons, development of social entrepreneurship but also development of perspective of purpose-driven universities71. In answering the research question, the article showed that so far service learning only partially influences youth employment: it enables some practical knowledge and skills for easier integration on the labor market but they, however, are still insufficient and point to the fact that the shortages in study programs are complemented with on the job training. Further on, the educational reform as well as a strong strategic framework for the social entrepreneurship are considered to be essential for increasing youth employment in Croatia. This article represents one of the first examinations of the relationship between service learning and social entrepreneurship in the Croatian context. The following recommendations are put forward based on the results of the research: • higher visibility and promotion of service learning is needed in the society in general and its stronger integration in the (higher) education system in Croatia as it may offer the required knowledge and skills for easier integration of youth on the labor market; • direct connections between teaching and community engagement is necessary as it directly contributes to the third mission of universities; • youth employment and social entrepreneurship development is to be fostered by way of clearly defined strategic framework; • recruitment of young employees should go beyond the Croatian employment services as they often fail to provide excellency in their services – this calls for reform and/or revisions in labor market policies, which involves also the Croatian employment services; • reform of the Croatian education system is also needed for matching the content and methods in educational programs with the labor market; interdisciplinary approach should be fostered as it possibly provides for new knowledge, skills and innovation. Future research may assess further the overlaps among service learning and social entrepreneurship and potential collaborations. Also, the reasons behind inability of social enterprises in Croatia to remain operational should be tackled in the future research. The dyadic nature of social entrepreneurship, which includes entrepreneurial skills and behaviors, and orientation towards the social mission, can present challenges for teaching social entrepreneurship. New careers in social entrepreneurship are on the horizon for young people in Croatia, so for the enhancement of their chances on the labor market and development of the field, students should be taught about social entrepreneurship in a proactive way, using the service learning methods. Service learning can be one of the ways to overcome those challenges and connect university education with the quest to solve social problems of the local community and help young people gain relevant skills for the labor market.

REMARK

LAG Cetinska krajina, LAG Međimurski doli i bregi, LAG Vinodol, LAG Posavina, LAG Izvor, LAG Papuk, LAG Laura, LAG Brač, LAG More 249, LAG Krka, Center for Sustainable Development, Croatian County Association, Croatian Employment Services – Regional Office in Split, Union of Association of Croatian Defenders Treated from PTSD Republic Croatia, Social Cooperative Humana Nova Čakovec, Association for Democratic Society, Veterans social-working cooperative Dalmatia Ruralis, Association of Unemployed Croatian Homeland War Veterans.