INTRODUCTION

Following the widely examined and researched Generation Y, a new generation has emerged. Similar to the previous generation a number of names have been used to describe it. These include: Generation Z, Gen Zers, Post Millennials (Bassiouni and Hackley 2014), Tweens, Baby Bloomers (K. Williams, Page, Petrosky, and Hernandez 2010), or iGens (Schneider 2015). Some researchers define Gen Zers as people who were born after 2000 (G. Armstrong and Kotler 2017), whereas others as those who were born in the 1996-2010 period (Monaco 2018). “While some analysts define Gen Z as those born 1996 to 2010, and others use the years 1997 to 2014”, the editors of Trends Magazine “prefer to use 2000 to 2017” (Trends Magazine 2017). For the purpose of this paper, Generation Z consists of those born between the late 1990s and the late 2000s.

While social networking sites (SNSs) and mobile applications can be standardized products, the way users interact with them varies greatly by culture (Goodrich and De Mooij 2013). The authors of this paper decided to focus more on the secondary information available on Gen Zers in the United States and Canada. Their high social and mobile applications penetration rates, large market size, high income level and readiness for new technologies make them more appropriate for generalizing the study finding on a global scale. North America had the highest mobile social media penetration in the world in 2019 (61%) (We Are Social 2019). The latter fact makes their population more likely to adopt digital travel applications and websites, especially when their national culture enjoy a low uncertainty avoidance (i.e., more likely to engage in new and unfamiliar experiences) (Hofstede Insights 2019) .They represented 27.6 percent (87.4 million) of the United States Population in 2015 (American FactFinder 2015) and nearly 23 percent (8.5 million) of Canada population in 2017 (Statistics Canada 2017). They are already bringing $44 billion to the American economy. However, it is predicted that by the year 2020, they will account for one-third of the United States population, and will be the strongest spenders (What travel companies need to understand about Generation Z 2017). As of 2019, many Gen Zers have already graduated from college, joined the global workforce and become independent working adults. In addition, the United States and Canada have high gross domestic product (GDP) per capita ($67,700 and $48,300 respectively), which makes them more likely to afford domestic and international travel (Central Intelligence Agency 2019).Bresman and Rao (2017) argue that Gen Zers in the two countries are homogenous in terms of their views on the importance of leadership and technology in their professional lives. The latter facts make the two populations more likely to be homogenous in the way they use social and mobile tools to book their travel.

Although several journal articles, books, and online sources have discussed their general and overall characteristics, hardly any studies have explored their behaviour, preferences and habits as travellers and guests. Meanwhile, most industries and organizations are aiming for this new generation and are tailoring their products and services to their needs. Some have even formed special lines or entire stores that are devoted to Gen Zers, such as Abercrombie Kids, Gap Kids, Old Navy Kids, and Pottery Barn Kids (G. Armstrong and Kotler 2017). However, how this new generation will impact the hospitality and tourism world has been ignored. It is especially important for hospitality and tourism marketers to carefully examine this emerging market segment in order to ensure that they will properly adjust to its attitudes and needs.

In marketing, there is no product that satisfies the needs of all consumers. Customers are too numerous, too widely scattered, and too varied in their needs and buying processes. Moreover, the companies themselves vary widely in their abilities to serve different segments of the market (Kotler et al. 2017a, 202). Therefore, it is important to acknowledge the major differences in behaviour between generations of travellers (Turen 2015). Demographic trends and changes in values and perceptions have a strong influence on consumer behaviour and marketing strategies (Yeoman et al. 2012). So far, very few studies have examined or mentioned how Gen Zers as independent travellers that go through their travel and hospitality services purchase decision-making process.Fuggle (2017) argued that marketing to Gen Z travellers will highly rely on developing short and compelling digital visual content that grabs their attention as Gen Zers have a 50% shorter attention span than Millennials (Cobe 2016).

According toG. Armstrong and Kotler (2017), the approximately 72 million Gen Zers make up important kids, tweens, and teen markets in the United States. They spend an estimated $44 billion annually of their own money and influence a total of almost $200 billion of their parents’ spending. These young consumers also represent tomorrow’s markets – they are now forming brand relationships that will affect their buying in the future. It would normally be expected that when it comes to consumer decision-making, as consumers, Gen Zers go through similar mental processes to older generations. However, the authors argue that as a unique demographic with their own unique set of characteristics, that mental process can differ from other demographics and industries.

A limited number of studies aimed to understand Gen Zers’ trends and preferences in travel (Trainee and Cole 2014;Turen 2015;Bradley 2016;Fuggle 2017;Trend Watch 2017). Other studies investigated the impact of specific issues such as social media, word-of-mouth and travel planning on the travel buying decision process (Pinto et al. 2015;Xiang, Magnini and Fesenmaier 2015). However, to this date, no study has ever provided a holistic conceptual understanding of Gen Z travellers’ buying decision process and of the potential of this segment to become the major segment of travellers in the United States and in Canada in the next two to three decades. Therefore, it is critical to set the foundation for a new understanding of Gen Zers’ social and mobile -making model in travel and tourism.

The authors’ research methods combine an extensive literature review with secondary data analysis of recent academic and professional reports. The authors rely on Engel-Kollat-Blackwell’s (EKB) consumer decision-making model andHoffman and Bateson’s (2017) consumer decision process as a theoretical base to combine and propose a novel social decision-making model for Gen Zers’ travel buying behaviour. This paper starts by illustrating the general characteristics of Gen Zers as consumers and travellers. Then, it explains how each stage of the decision-making process has changed by technology, generation and industry-specific factors and how a new model could emerge based on all this new information. Also, this paper addresses the significant implications (both theoretical and practical) that derive from the careful analysis of Gen Z travellers’ needs and motivations, their approaches to information search and how they compare the various travel alternatives, as well as to the way they evaluate their purchased travel experience. More specifically, this paper explains how these implications can affect the hospitality and tourism industry and offer ideas and suggestions on how to effectively approach this new generation of travellers. This paper suggests that travel and hospitality service providers should rethink their offering such as room and meal options, locations, facilities, room amenities and technology infrastructure and make the necessary changes that will carefully address the needs of Gen Zers. In addition, this paper aims to help marketers rethink and possibly revise their brand core messages, content, segmentation, positioning, advertising and communication in order to better appeal to Gen Zers at each stage of their decision-making process.

The General Characteristics of Gen Zers

Generally, American and Canadian Gen Zers are the first wholly-digital generation, which means that they have grown up using the internet and smartphones (Williams 2010;Wood 2013). Unlike Millennials who use three screens on average, Gen Zers use five: a smartphone, TV, laptop, desktop, and iPod/iPad (Abramovich 2015). It is quite impressive that “on average, connected Gen Zers receive more than 3,000 texts per month” (G. Armstrong and Kotler 2017), which clearly illustrates how extremely mobile, connected, and social this new generation is. Also, they are more: realistic (Gale 2015;Jennings 2017;“Understanding Generation Z” 2015;K. C. Williams and Page 2011), self-aware ("TREND #3: Generation Z Gets Serious About Consumption" 2017;A. Williams 2015;K. C. Williams et al. 2010), multi-tasking (Armstrong 2016), conservative, conforming, peace and security-seeking, collective, environment and sustainability-oriented, and value peer acceptance (Williams et al. 2010). Most importantly for this paper, though, they are more independent in their digital information search and decision-making processes (Bassiouni and Hackley 2014;Schneider 2015) compared to other generations, e.g., their closest-preceding and extensively-studied generation, millennials, who are also known asGeneration Y, Wood (2013) contended that Gen Zers can be more receptive of “escapism” goods such as dining out and virtual experiences, whileBradley (2016) noted that they are more influenced by opinion leaders on social media.

Numerous studies portray Gen Zers as having a shorter attention span (Cobe 2016;"TREND #3: Generation Z Gets Serious About Consumption" 2017;K. C. Williams et al. 2010;S. Williams 2010). However, businesses and marketers need to widen their own understanding of that stereotype. It is important to consider that technology-enabled efficiency tools and informed decision-making are significant factors that simply reduce the time needed to be attentive (Roberts 2016). These studies supported that Gen Zers process many types of information simultaneously, e.g., respond to personal chat, see ads, watch videos, read articles, study, etc., which in turn results in less time to allocate for each part and type of information and devices (Armstrong 2016;Marks 2016;S. Williams 2010). Gen Zers not only expect innovation in products and services, but also expect to access those innovations conveniently (Wood 2013). Gen Zers respond more to visual communication such as photos, videos and rich content compared to text (Marks 2016). Additionally, they are best reached through mobile (Schneider 2015), are quite demanding, and expect extreme degrees of personalization as well as immediate responses to their requests. For example, they will abandon someone due to slow response in an online chat or if customer service is only available over the phone or in person. Gen Zers are also considered realistic and determined. They are more informed in decision-making and more receptive to genuine brand communication messages compared to Millennials (Hulyk 2015).

Abramovich (2015) described Gen Zers as adept researchers who know how to self-educate and find information. The author also provided some interesting statistics about them: 33% of Gen Zers watch lessons online, 20% read textbooks on tablets, 32% work with classmates online, and 79% of Generation Z consumers display symptoms of emotional distress when kept away from their personal electronic devices. According to a study by The Center for Generational Kinetics (2017), “52% of Gen Z even uses ratings and reviews while shopping at a retail store to compare shop or price match online while physically in the store” and this generation will not buy anything “without getting feedback from other customers, who they trust implicitly” (23). That same study also found that “30% of Gen Z prefers to get information on a brand from a real customer of the brand and 19% from an online influencer, meaning a well-known blogger, YouTube or internet personality, etc.” and that “friend and family recommendations are the most influential source of brand choice for Gen Z” (The Center for Generational Kinetics 2017, 22). Gender differences in the purchase preferences of Gen Zers were also reported. More specifically, the study found that “Gen Z guys prefer to spend more on products than Gen Z girls, and Gen Z girls want to spend more on experiences than their male counterparts” (The Center for Generational Kinetics 2017, 20).

The Travel and Tourism Characteristics of Gen Zers

Gen Zer travellers in the United States are mainly leisure-seeking, budget-cautious and domestic travellers. A study conducted byExpedia Media Solutions (2017a) revealed that only 23% of Gen Zers would travel outside the United States, 58% of Gen Zers prefer to stay at a hotel, 18% choose friends and family, 11% of Gen Zers would prefer to stay at a resort, and 8% would choose alternative accommodations. Furthermore, when Gen Zers first decide to take a trip: 9% of them doesn’t have a destination in mind, 55% of them decides between two or more destinations, 35% of them have already decided on a destination. In addition, 69% of Gen Zers prefer all-inclusive vacations like resorts and cruises, 70% are all about taking a nap on the beach, spa treatments and all-day relaxation, and 58% of Gen Zers plan all their travel around where and what they eat and drink. Moreover, 71% of Gen Zers prefer to go to museums, historical sites and arts and culture fill up their travel itinerary. Gen Zers “travel nearly 30 days a year and although they have a budget in mind when planning a trip, they invest in travel, and are more likely than other generations to travel internationally” (Expedia Media Solutions 2017a, 22). Gen Z travellers demand more personalized experience, unconventional destinations and more emersion in local cultures (Trend Watch 2017). It is also critical to note that Gen Zers are characterized as one of the most budget-conscious generations in Europe.

The Expedia Media Solutions’ (2017a) study revealed some interesting statistics and information about the travel preferences and habits of Gen Zers. More specifically, when asked which of the following social media sites influence or inspire their decision making process in booking, 64% of Gen Z chose Facebook, 46% chose Instagram, 35% chose Twitter, 23% chose Pinterest, 27% chose Snapchat, 1% other and 13% claim that they are not influenced by social media. Furthermore, 90% of Gen Zers look for deals before making a decision, 86% agreed that informative content from destinations and/or travel brands can influence their decision-making process, 82% admitted that they read reviews of places they want to visit from sites like TripAdvisor before making their final decision, 76% talk to people who have visited the place before making a decision, 65% agreed that ads can be influential in their decision-making process, and 58% noted that they use loyalty programs in their decision-making process. When it comes to using their smartphones, 67% of Gen Zers use it when they are looking for inspiration on where to travel, 44% use it when they are researching on where to travel, 27% use it when they are booking their travel and 78% of them use it during their trip. However, when asked the same questions in relation to using a desktop or laptop, significant differences in those percentages were reported. These were as follows: 69% of Gen Zers use it when they are looking for inspiration on where to travel, 82% use it when they are researching on where to travel, 83% use it when they are booking their travel and 37% of them use it during their trip. In terms of their travel personality, “93% of American Gen Zers are looking for the best deals and most value for their dollar, 83% of them would go anywhere that allows them to explore the outdoors and be active and 78% would opt for off the beaten path locations and recommendations from locals (Expedia Media Solutions 2017a, p.15). Interestingly, these percentages were quite lower for their European counterparts (Expedia Media Solutions 2017b, p.22). More specifically, 86% of European Gen Zers are looking for the best deals and most value for their dollar, 75% of them would go anywhere that allows them to explore the outdoors and be active and 65% would opt for off the beaten path locations and recommendations from locals.

Gen Zers are “well-travelled from an early age and globally minded, and thus interested in offbeat destinations” and are very interested in “Instagram-worthy designs that continue to drive the popularity of boutique hotels” (Trend Watch 2017, 1). Others (Globetrender 2018) supported that Gen Zers play a key role in the holiday-booking decision-making of their parents. According to the findings of a recent study conducted by the Royal Caribbean International, 95% of parents “believe their children’s happiness is more important when going abroad and carefully listen and check their kids’ with them about their wants needs and preferences related to the trip before booking” (Globetrender 2018).

As recipients of travel marketing and brand messages, research revealed that 22% of Gen Zers are more likely to prefer in-app notifications, whereas 23% are more likely to prefer social media marketing than Millennials (RRD Communications 2018). On the one hand, this clearly shows that Gen Zers are strong mobile users. On the other hand, it signals that marketers need to understand that Gen Zers’ preferences, habits, and way of thinking form an entirely different market segment. As far as travel rewards are concerned, not only are they fond of member-only discounts and free samples like millennials, but they are also more likely to prefer personalized promotions and physical cards loyalty programs (Crowdtwist 2016).

CONSUMER DECISION-MAKING: THE CLASSICAL MODEL

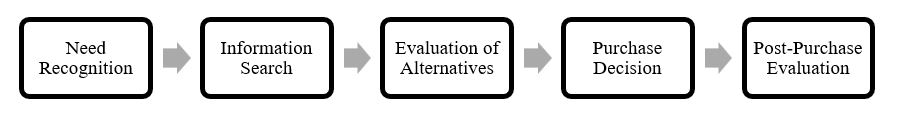

In general, consumers go through a typical mental process when it comes to making a decision to buy a product or service.Simon's (1959) buying decision process, later extended by Engel-Kollat-Blackwell (EKB) consumer decision-making model, is one of the most prominent marketing theories which explains step-by-step the five stages of that mental process (Darley, Blankson and Luethge 2010). EKB model is presented inFigure 1.

According to this theory, it all starts with the need recognition stage, where consumers recognize the need to buy a product or service. This need can be triggered by internal stimuli, e.g. one’s previous experience or external stimuli such as watching a television commercial for a hotel. The second stage is the information search where consumers start seeking information to learn more about their intended purchase. Sources of information include: personal sources such as family or friends, commercial sources such as salespeople and advertising, public sources such as restaurant reviews and editorials in the travel section, internet such as a company’s website and experiential sources which refer to examining and using the product (G. Armstrong and Kotler 2017;Kotler et al. 2017). The third stage is the evaluation of alternatives where consumers process all the information at hand in order to shortlist and choose among alternatives products and brands. The type of evaluation and the number of criteria that consumers use depends on the individual and the specific buying situation. For example, some consumers may turn to friends or online reviews for advice while others might go with their gut instinct instead of doing any evaluation at all (G. Armstrong and Kotler 2017). The fourth stage is the purchase decision where consumers finally make their choice. Generally, the consumer’s purchase decision will be to buy the most preferred brand, but two factors can come between the purchase intention and the purchase decision: a) the attitudes of others and b) unexpected situational factors such as an expected income, price or product benefits (G. Armstrong and Kotler 2017;Kotler et al. 2017). The fifth and final stage is the post-purchase evaluation where consumers evaluate their purchase after buying it. The relationship between the consumers’ expectations and the product’s perceived performance determines the consumer’s feelings about the purchase (G. Armstrong and Kotler 2017). So, they may either be happy and satisfied or dissatisfied and disappointed with the outcome of their purchase.

As noted bySimon (1959), consumers attempt to make rational decisions when they buy something. However, their final decision, as well as the stages before, are never free of personal bias, subjectivity and emotions (Wei 2016). The most important part of the analysis of this stage is that regardless of how the consumer may feel, they will certainly exhibit postpurchase behaviour that is extremely interesting and valuable for marketers to examine (Armstrong and Kotler 2017). Satisfied customers “buy a product again, talk favourably to others about the product, pay less attention to competing brands and advertising, and buy other products from the company” (G. Armstrong and Kotler 2017, 151). However, the way unhappy and dissatisfied customers express their concerns varies significantly. According toDimitriou (2017) in hospitality and tourism organizations, those dissatisfied customers might choose to “directly express their concerns face-to-face to the hospitality employee, supervisor, or manager on duty. On certain occasions, they will even demand to speak directly to the general manager the very instant the service failure occurs or at some point prior to leaving the premises. If their voice is not heard, then they will most likely turn to the social media or websites like TripAdvisor or Yelp to write a review, submit their complaint and inform others about their experience. Some guests will choose a less confrontational way of registering their complaint such as sending an email or writing a letter upon their return home, which will include all the details of what went wrong. Others prefer to fill out a comment or feedback card upon their departure knowing that it will be sent to management and hoping to hear from them soon. Some choose to place a phone call to the customer service line or directly contact the headquarters and submit a formal complaint through the company’s online complaint form so the problem can be resolved through the much higher-up management. There are also guests who do not want to be bothered, they let go of the bad situation or experience, move on and usually never return to that hospitality organization, while others will bypass any sort of interaction with the hotel management or staff and go directly to the internet to report their complaint” (17).

CONSUMER DECISION-MAKING: SUBSEQUENT MODIFIED VERSIONS OF THE CLASSICAL MODEL

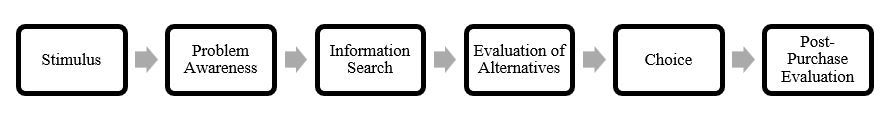

Another perspective on consumer decision-making was introduced byHoffman and Bateson (2017) and is illustrated inFigure 2. According to this model, need recognition is replaced by problem awareness and is no longer the first stage in consumer decision making. They contended that before realizing a need, problem or want, consumers are motivated by commercial (e.g., advertising), physical (e.g., thirst), or social cues. In other words, a certain stimulus or stimuli trigger problem recognition, thus adding an extra step and turning the original five-step process into a six-step one. WhileHoffman and Bateson (2017) used different names for some of the original stages of this process (e.g., choice instead of purchase decision and problem awareness instead of need recognition), the meaning behind what happens in these steps remains the same.

In recent years, the studies mentioned below have recognized the need to modify the initial decision-making model and adjust it to the new standards and ever-changing needs of consumers. Therefore, the model has become internet-based, complex and fast. The rise of social media, mobile devices and the limited attention span of Gen Zers greatly affected the classical model of consumer decision-making (Bassiouni and Hackley 2014).Wei (2016) contended that the stages of the online decision-making process have become more interrelated (i.e. happen simultaneously instead of sequentially). Travel and hospitality marketers need to understand that the process is wholly-digital and happens on multiple channels simultaneously (Gale 2015). Also, they need to realize that technology shortens the overall duration of the decision-making process. In other words, marketers have less time, now, to influence the consumer’s decision at each of these stages.

CONSUMER DECISION-MAKING: A NEW PROPOSED MODEL FOR GEN ZERS TRAVEL BUYING

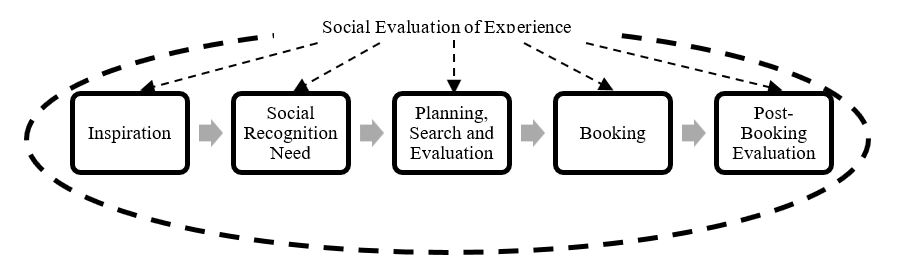

The authors argue that the existing models of buyer decision-making process must be revisited and re-evaluated to better address the changing behaviour of new consumer segments. The section below explains the theoretical foundation of the authors’ proposed travel social decision-making model for Gen Zers in light of the discussed theories and literature. This new model consists of five stages with the addition of a critical component and is presented inFigure 3.

The First Stage: Inspiration

When it comes to the first stage of Gen Zers’ buying decision-making process, the authors strongly agree withHoffman and Bateson (2017) that need recognition can no longer be considered as the first stage and that a certain stimulus is required prior to that.Mintzberg, Raisinghani, and Theorêt (1976) found that in at least 18 out of the 25 examined cases, “the decision processes were evoked by many stimuli, originating both inside and outside the organization” and that even though a decision can be based on a single stimulus, “it may remain dormant in the mind of an individual until he is in a position to act on it” (253). Additionally, there’s another argument that supports this idea. For Gen Zers, being aware of a need or want to travel does not explain fully their true intentions, benefits sought, and motivations to travel. Stronger social recognition and desire to imitate opinion leaders and influencers become critical in shaping and creating their needs or wants to travel (Trainee and Cole 2014;Marks 2016;Chatterjee et al. 2018). Therefore, this could serve as a great stimulus for them to desire travel.

It is important to note that this generation is constantly online through the variety of electronic devices they have access to. This simply means that they are in a continuous search for new information and a continuous evaluation of the possible alternatives that come up regardless of whether they may have an intention to buy a travel package or not. This behaviour is demonstrated by their continuous content consuming, scrolling, texting, and watching videos on their smartphones. To them, random and continuous seek of experiences, information and novelty is a habit and sometimes even an addiction (Saaid, Al-Rashid and Abdullah 2014). This is so true when taking into consideration the abundance of options and information that are offered online, and the ease of access and exposure that Gen Zers have to all these sources. So, there has to be something on the mobile application or the website they “randomly” visit that will attract their attention and get them interested in wanting to know more about it. This could be a blog, video, or article that has attractive content about a travel destination, a traveller’s review or a simple comparison of two travel service providers by an expert traveller. It all starts with that inspiring stimulus that gets them excited about a travel opportunity.

The Second Stage: The Switch from Need Recognition to Social Recognition

Once Gen Zers get the stimulus that arouses their interest about a travel destination or another vacation opportunity through their random surf on the internet, then they start recognizing the need to travel. This is the part where they start to realize that this stimulus, e.g. an exotic destination at a very affordable price they saw online, could potentially be an exceptional reason to plan a winter getaway or recognize that they do need a break from it all and this is a great opportunity to take advantage of.

Although, some people might argue that when it comes to the need recognition stage, the factors that get Gen Zers to travel are the same with older generations.Pearce and Lee (2005) indicated 14 motivational factors for people to travel, in general. The most important factors include: escape/relax, novelty, and kinship. Nevertheless, the reasons that trigger Gen Zers’ need to travel are unique and specific to them. They proactively seek to know different cultures, meet new people and establish overseas friendships (Broadbent et al. 2017). Peer recognition and acceptance are key to Gen Zers (Pólya 2015). Moreover, this generation feels the most comfortable sharing personal photos and videos with their peers and public as ways of achieving self-actualization and emotional fulfilment (Trends Magazine, 2017). Peer influence is a key factor that impacts their purchase intention (Mohammed 2018).Machová, Huszárik and Tóth (2015) argued that Gen Zers are less influenced by traditional advertising, whileSterling (2017) supported that they need a more authentic and ‘real life’ communication and dislike any non-skippable pre-roll ads and pop-ups while surfing the internet. The author also addressed the important role that social media influencers play in their purchasing decisions and how they seek and appreciate their recommendations. Furthermore, European Gen Zers are more likely to seek once in lifetime experiences than any other European generation (Skift 2018), which could possibly generate admirable social media posts. Consequently, Gen Zers’ need recognition to travel cannot be separated from their need for social recognition.

The Third Stage: Planning, Search, and Evaluation

Gen Zers can find information and compare travel alternatives better than any other older generation. According toExpedia Media Solutions (2017a), 67% of Gen Zers use their smartphones to look for inspiration on travel destinations. Also, 90% of them look for deals before booking. Gen Zers use multiple sources to find trusted information when planning a trip. Their information search is faster and more informed compared to earlier generations (Gale 2015). Gen Zers usually do information search through integrating online and offline channels (K. Williams and Page 2011).

Some authors (Armstrong and Kotler 2017) supported that more than half of all Gen Zers in the United States conduct a product research before buying a product or having their parents buy it for them. Another study (Expedia Media Solutions 2017a) found that Gen Zers, like Millennials, rely primarily on online travel agencies (43%) and search engines (53%) to search for information and plan trips. However, Gen Zers’ information search is more socially-influenced and meticulous. More specifically, 82% of Gen Zers read reviews of places they want to visit on travel reviews websites, 76% of them talk to people who have visited the place before making a decision, 36% of them discuss with family or friends, 32% of Gen Zers compare travel sites and 30% visit, and explore hotel sites, and 62% agree that advertised deals that look appealing do influence their decision-making (Expedia Media Solutions 2017a).Yesawich (2013) also argued that Gen Zers rely primarily on social media to communicate and look for information about travel and use multiple devices in their searches, such as laptop, mobile and desktop. In fact, when asked about the resources they used to book a travel online on their last trip, the results of theExpedia Media Solutions’ (2017a) study showed that 46% used online travel agency, 36% used hotel sites, 34% used airline sites, 15% used car rental sites, 17% used destination sites and 16% used alternative accommodation sites.

It is also important to note that there are two things that Gen Zers value most: Ease and speed of navigating a website or an app while researching purchases or shopping (Donovan 2017, 1). As a matter of fact, almost half of them admit that “the most important thing while shopping is to find things quickly”. If an app or website is too slow over 60% say they will not use it” (Donovan 2017, 1). As marketing researchers (G. Armstrong and Kotler 2017;Kotler et al. 2017) noted, the more information consumers are gathering, the more knowledgeable and aware they become of the products and services that are available.

Gen Zers tend to use a non-compensatory approach when choosing between alternatives. More specifically, they utilize the elimination-by-aspect model. According to this model, consumers eliminate the alternative(s) that do not meet a minimum accepted cut-off point in certain criteria, (e.g., room cleanses, price, safety, etc.) (Tversky 1972). Gen Zers particularly use reviews and ratings as a primary tool to narrow their list of alternatives (Gretzel and Yoo 2008). When comparing travel options or evaluating alternatives, Gen Zers are less focused and probably doing other tasks at the same time, also known as multitasking (Beall 2017).

As younger consumers, Gen Zers are less loyal to brands compared to older generations. They utilize more alternatives to choose from. They process more information and criteria per alternative thanks to a relatively stronger working memory (Cole and Balasubramanian 1993). Technology helps Gen Z to be more efficient in their evaluation of alternatives. In recent years, mobile apps have gone far beyond Airbnb, real-time price comparison, guest reviews, photos and videos. Now, apps empower users with more personalized suggestions and recommendations on destinations based on traveller’s history, current location, and interests (Chokkattu 2018). For example, the Hilton Honors app includes a feature called FunFinder for the hotel company’s loyal members, which acts as a personal travel guide (Hilton Honors 2016). It knows guests’ preferences and offers recommendations based on their arrival and departure information, preferences collected in a pre-arrival survey, the current time and their location in the resort. Virtual reality (VR) apps and wearable technologies start building solid footsteps in the travel industry (Alexander and Natarajan 2017). Furthermore, social travel apps are another emerging trend of apps where adventure-seeking travellers can connect and share entire travel experience.

The authors support that evaluation criteria can be different from one generation to another. When comparing travel sites, flights, hotels or activities, Gen Zers’ most important criterion for evaluation is price. Combined with their “sharing” economic thinking (i.e., share costs of services with others), they would weigh the cost criterion the highest. However, they do not consider it as a solely determinant (Biesiada 2018). Accordingly, they consider sharing options in accommodation, cars and activities as another important criterion. When comparing travel alternatives, the tool used (e.g., mobile app or website) becomes an important evaluation criterion itself. Speed of booking and personalized recommendations become key criteria for Gen Zers (Alexander and Natarajan 2017). Service quality is another important criterion for Gen Z travellers (Liu et al. 2013).

The Fourth Stage: Booking

When European Gen Zers decide to book a trip, 14% do not have a destination in mind whereas 29% of them already do, 57% of them are between two destinations when they first decide to take a trip (Expedia Media Solutions 2017). The same study revealed that 55% of them are between two or more destinations and only 35% have already decided on where to go (12). This means that the inspiration they were exposed to on social media has influenced them to choose a particular destination or experience. Even when travelling with their families, they are the most influential in choosing the destination (Trend Watch 2017). Gen Zers’ decision to travel has a more hedonic and emotional nature. They decide to travel because they want to live a new adventure, meet new culture or spend an enjoyable time (Pólya 2015;Chatterjee et al. 2018).

Once Gen Zers have made up their minds on where they want to go, they need to decide on which website, mobile application or tool they use to plan and book their trip. For Gen Zers, this decision is mostly rational. Their budget constraints, digital savviness, and lower brand loyalty (Stokoe 2015) are key determinants of the travel platform they will choose to buy from. Most digitally-native travellers even use different websites or mobile applications to plan their travel than the ones they use to make the actual booking (Peterson 2015). American Gen Zers’ decision to book the travel is also financially-focused. Ninety percent of them primarily look for the cheapest price and best deals possible to book their travel and fifty-eight percent of them use loyalty programs in their decision-making (Expedia Media Solutions 2017). What’s even more interesting is that their travel purchase decision is strongly influenced by opinion leaders on social media and travel sites reviews (Gretzel and Yoo 2008;Pinto et al. 2015).

The Fifth Stage: Post-Booking Evaluation

When it comes to the final stage of the buyer decision process for Gen Zers, consistent with the previous models, the authors agree that a post-purchase evaluation takes place, which in the proposed model is called post-booking evaluation. This is the part where Gen Zers as travellers/guests/passengers, etc. look back at the whole travel experience and compare their initial expectations and travel plans to the benefits they received and the extent to which those expectations were met, unmet or exceeded. At this stage, failure to meet expectations, most definitely leads to dissatisfaction and cognitive dissonance, which refers to buyer discomfort caused by post-purchase conflict (Kotler et al. 2017).

On the one hand, Gen Zers’ post-purchase evaluation can be extremely challenging for businesses. Their post-purchase evaluation is timely, fact-based and rational. Electronic word of mouth (eWOM) and user-generated content are integral parts of Gen Zers’ post-purchase evaluation (Liu et al. 2013). Gen Zers are the generation with the highest expectations (Beall 2017) and lower brand loyalty (Wood 2013). In addition, they enjoy a low switching cost (i.e., will not lose much money or time to change their favourite travel app or website) having numerous innovative travel booking apps and service providers. On the other hand, online travel as a global industry is extremely price-sensitive where prices are fixed among a few large service providers (Chatterjee et al. 2018). Accordingly, travellers’ demand can be inelastic in many cases in response to cost or experience variables, which in turn impacts their post-purchase evaluation negatively or positively.Park, Cho and Rao (2015) contended that post-purchase service quality strongly impacts college students’ positive post-purchase evaluation, repeated purchases, and satisfaction.Xiang et al. (2015) argued that technological advancements in the travel and tourism industry have affected how people evaluate their overall travel experience and perceive its usefulness. Many mobile apps and websites guide, and sometimes, even force travellers to “plan” their trips and travel activities in advance. Having a detailed plan and means to notify travellers in case of plan changes reduces uncertainty and helps to improve the actual travel experience, and in turn, improve the evaluation of the travel provider. For example, a travel planning mobile app that automatically tracks flight information and notifies travellers in advance about a possible or unexpected delay, can save travellers’ time and money and improve their overall experience with an airline.

The Additional Component of the Proposed Model

According toWei (2016), the stages of the online decision-making process have become more interrelated (i.e. happen simultaneously instead of sequentially) which holds true in the case of Gen Zers. Moreover, the authors agree with the earlier literature that described the recent decision-making model as internet-based and more complex (Gale 2015;Hulyk 2015). So, a new key factor that comes into play for the buyer decision-making process of this new generation. Throughout the entire process and at each step of the way, the social evaluation of the entire experience is present. This generation is hooked on technology and social image, reputation, and recognition. In addition, what their friends, opinion leaders, and peer feel or say truly matters to them. Regardless of the stage they are in, Gen Zers are constantly online, connected to the internet, social media, and all kinds of websites, reading, checking, comparing, analysing, and evaluating options, information and ideas in order to ensure they are making the most out of the whole experience and meeting their goals.

THEORETICAL IMPLICATIONS: THE NEW TRAVEL SOCIAL DECISION-MAKING PROCESS FOR GEN ZERS

Gen Zers are the most important future guests and travellers in the hospitality and tourism global market. This new generation is significantly different in various ways compared to previous generations, especially when it comes to how they plan and organize their vacation trips and other forms of travel. The authors believe that understanding their decision-making process is a good place to start.

An important change that takes place and is introduced in the new social travel decision making-model process is a component called the Social Evaluation of Experience. This is a continuous process of social evaluation and refers to an ongoing activity that is integrated and takes place throughout the entire process. The authors explain that the reasoning behind that is simply because the mental stages for Gen Zers in this digital age are more interrelated and connected than ever.

The authors contend that inspiration is the trigger of the entire process, not need recognition. Therefore, it should be the very first stage in this model. A certain stimulus must arouse Gen Zers’ interest that is strong enough to create a need that they would be willing to pursue. This inspiration stage is more hedonic, emotional, fast, and spontaneous. Gen Z travellers must be inspired, not attracted. They are inspired when they see something that is untraditional, innovative and unique. Something that directly relates to their aspirations and “speaks” their language in a new way that they have not seen before.

At the second stage, the inspiration creates a need. The need, problem or want created at that stage stems from the stimulus or stimuli that came up in the initial stage. The stronger the social or commercial stimuli is, the stronger the need recognition will be. For example, if Gen Zers watch a video of their favourite influencer, blogger or close friend at a travel destination, they will realize a stronger need to travel compared to watching a random advertising video. At this stage, apart from realizing a need to travel, Gen Zers also realize a need to be socially recognized (i.e., posting their own videos and photos to be liked and shared).

The authors argue thatMintzberg et al.'s (1976) two stages of information search and evaluation of alternatives should merge into one stage for Gen Z travellers. This new consolidated stage is the core of the new decision-making process and is entirely dependent on technology, attractiveness, and usefulness of the travel website or application. Information technology, social media, mobile applications, websites and multi-device usage patterns allow Gen Zers to easily plan, compare and search for all information possible simultaneously. Researching a potential vacation experience is no longer separate from planning the trip day-by-day and evaluating different service providers. For example, mobile applications such as TripPlanner automatically track travel confirmation emails and automatically create daily activities calendar for travellers with mobile notifications and reminders. Other online booking platforms such as Kayak allow travellers to compare airline tickets from various providers to the same destinations and allow viewing best times or days to book tickets.

Perhaps the most important stage for service providers is the fourth stage: booking. This is where Gen Zers actually complete the transaction and commit to paying for their trips. At this stage, Gen Zers are expected to have a more informed decision after an extensive and savvy planning stage. This means their cognitive dissonance (i.e., regretting their decision) and risk perception should be lower than other generations. This stage is expected to be extremely rational and objective. Instead of relying on brand loyalty to book their travel, they select the option that makes most sense to them and is the result of careful consideration.

Gen Zers as travellers are likely to pass through an extended and rich post-booking stage. They are expected to evaluate their entire booking experience and the actual travel experience, which are two entirely different realities, but strongly interconnected (Xiang, Magnini and Fesenmaier 2015). Naturally, the post-booking stage is expected to strongly influence their future travel and service provider choices and recommendations to peers (Saaid, Al-Rashid and Abdullah 2014).

In addition to these five stages, the authors suggest an ongoing activity that Gen Zers are expected to conduct along with their entire experience, the so-called social evaluation of the experience. Unlike previous models that suggested post-purchase evaluation as the definitive end of this process, the authors introduce an additional kind of real-time evaluation, on different aspects (i.e., application usability, agent friendliness, prices, etc.), and through multiple channels (i.e., phone, web, social media, wearables, etc.). The content of this new type of evaluation is also expected to be dynamic. Rating and content can rapidly change from positive and negative or vice versa. Content can be added and third parties can join and influence the evaluation. Also, evaluation can be significantly magnified in a short period of time.

PRACTICAL IMPLICATIONS: MARKETING INSIGHTS TO ATTRACT GEN Z TRAVELLERS

The authors contend that the travel and tourism industry must learn more about the special preferences and lifestyles of Gen Zers. In addition, they must use that information to create new products and experiences that capture this specific market segment. Indeed, this can be quite challenging taking into consideration that Gen Zers are “notoriously fickle and hard to pin down” (G. Armstrong and Kotler 2017, 76).

Indeed, travel and tourism service providers should: 1) Create niche and innovation-based marketing strategies; 2) design compelling mobile applications; and 3) find creative ways to offer low-budget travel packages. The authors argue that carefully examining these motivations, special preferences, travel characteristics, and lifestyle of can engage Gen Zers and enable them to co-create their own experiences, travel products and ideas, which leads to sustaining business success.

In terms of reaching out to Gen Zers, the authors urge travel and tourism marketers to segment Gen Zers by nationality, interests, lifestyle and culture in addition to accurate age segmentation as these factors can significantly influence their behaviour. Also, behavioural segmentation (i.e., hours spent online, type of content consumed, activities in travel, etc.) is another important strategy for markets to consider. For example, when a sample of Europeans were asked about the key influences in their decision-making process, British travellers were the most likely to look for deals before making decisions, but they also found reviews and informative content persuasive. German travellers indicated that reviews of places and informative content can influence their decision-making process followed by a slightly lower emphasis on deals. French travellers showed a slight preference over German travellers for talking to people who have already visited a destination, but reviews of places are still the most persuasive. Another example refers to what Europeans do while on vacation. “British travellers more often go on sight-seeing vacations. German travellers are more likely to seek relaxation and activities. French travellers prefer visiting family and family fun more than the British or Germans (Expedia Media Solutions 2017b, 20). This will allow marketers to pick and choose those specific groups that match their criteria and are the most appealing and worth investing in.

Marketing on the right channel is no longer enough, marketers should be specific about the exact marketing vehicle or platform (e.g., Facebook versus Instagram) and the exact device.Yesawich (2013) talked about the Digital Elite which refers to “active travellers who are users of three digital devices: laptops, smartphones and tablets” and pointed out that “eight out of 10 are on Facebook, three out of 10 are active on Twitter and two out of 10 frequent YouTube, Google+ and Pinterest” and that these guys “are also more inclined to share travel experiences in ‘real time’ than their less-connected counterparts” (14). In addition,Yesawich (2013) noted that “only one in 10 Digital Elite cites choosing a travel destination (11 percent) or service provider (10 percent) based primarily on photos or videos viewed on social media” and that “almost half of the Digital Elite begins sharing commentary and visuals during vacations (49 percent)” (13). Furthermore, when he compared the digital Elite to less-connected travellers he found that even though TripAdvisor still is a major consulting source for seven out of 10 (67 percent) in both groups of travellers who visited online communities, travel forums or blogs to seek and/or review information about destinations or travel service providers, significant differences were reported in the following areas: 40% of the Digital Elite seek and/or review travel information on Facebook compared to the 26% of less-connected travellers, 23% of the Digital Elite seek and/or review travel information on YouTube compared to the 16% of less-connected travellers, 17% of the Digital Elite seek and/or review travel information on Google+ compared to the 10% of less-connected travellers, and 15% of the Digital Elite seek and/or review travel information on Twitter compared to the 5% of less-connected travellers (Yesawich 2013).

These data reveal how tech-savvy and digital native market segments such as the Gen Zers rely on social media as their way of communication. In fact, the authors agree with Donovan (2017) that companies must “provide interactive and personalized experiences that are current with the latest digital advances” (1) to appeal to this target market and build customer loyalty. For example, it is not enough to just launch a mobile application. It is more important to launch an effective one, especially at the present time as this is probably the most strategic investment for a travel or tourism business. Thus, the specific mobile applications must be well-planned, structured, and organized through careful user experience methodologies. Poorly-designed and cheap mobile apps would lead to questionable and mediocre quality. The apps must look attractive, fast and bugs-free. What is even more important, though, is that mobile applications should allow seamless offers and comparisons as well as integration with social media and travel reviews sites and blogs.

Early at the decision-making process, getting Gen Zers inspired is the hardest, yet most rewarding activity for travel and tourism marketers. This highlights the importance of customer intelligence and marketing product innovation as the new core of travel marketing strategies. Travel service providers, especially smaller start-ups, must find a niche travel product. Then, they need to design, advertise, and promote it better than any other competitor and communicate it to the appropriate and strategically targeted Gen Zers group or category. Travel and tourism providers must dedicate special business units that create, use and follow non-traditional “travel product marketing strategies”. Those business units should continuously research, test, and launch travel product marketing ideas that are catered for Gen Z travellers. Those business units should include marketing, operations, and highly-trained technology experts. Those units’ outputs could include, but not be limited to real-time live feed from multiple travel destinations, a local event for a specific activity at a specific destination, a charity-related initiative or an online game. Those types of product marketing solutions could prove to be much more effective than traditional digital ads targeting Gen Zers. This suggested niche and focused approach should also continue on a tactical level. For example, “cheap hotels in Paris” are no longer enough as an appealing advertised keyword on search engines. Instead, travel and tourism marketers should focus on promoting more niche travel products such as “beginner rafting northern Thailand”, “swimming with sharks San Diego”, or “crafts workshops in Florence”.

Furthermore, it is important for marketers to realize that traditional photos of beautiful super models relaxing at the beach that were so extensively used in the past are no longer inspiring to Gen Zers. This new generation of travellers is strongly inspired by peer-created, authentic, real experience photos and videos of real places that locals actually experience. These engaging and authentic rich media forms or ads should target each traveller based on his/her own likes, hobbies, communities and interests. Targeted ads on social media should be consistent with the current trends and designed, tailored, and focused on this generation’s specific psychographics and online behaviour. Ads should include and present authentic content made by amateur or home cameras, selfie photos, and videos from actual users of travel and tourism products and services. Additionally, online content and video ads should contain activities that are unique to the travel destination and capture action and excitement, as they are key elements that Gen Zers highly appreciate and value.

According toMcBride (2016), Gen Zers are highly committed to sustainability and environmental issues and truly value hotels that implement environment-friendly policies. Similarly, travel and tourism marketers could use this information to design competitive products and services that Gen Zers would find desirable. Indeed, this would be a win-win situation for everyone. It would benefit both travel and tourism providers and guests. More specifically, travel establishments would publicly benefit from doing their part to conserve the environment while appealing to that new target market. Furthermore,McBride (2016) noted that Gen Zers seek exposure to local cultures and a more local, less branded travel experience and suggested that hotels should offer a sense of local authenticity, (e.g. a hotel provides access to a local coffee shop, not a Starbucks). The authors feel that this would certainly apply to the travel and tourism industry, as well. Travel and tourism providers could focus on promoting the authentic aspect of their destinations and design products and services that embrace and respect the beauty and authenticity of local cultures and traditions.

Another critical factor to attracting Gen Zers is the recruitment of opinion leaders. First of all, travel and tourism marketers should conduct more research on the popular social media influencers to know who has the strongest impact on their specific target markets. Once those are identified, marketers should carefully implement strategies to recruit them and collaborate with them on setting clear marketing objectives. Travel and tourism marketers should be flexible to allow influencers the enough room for creativity and spontaneity. However, marketers should be ready to step in to check, monitor, and ensure that the influencers’ posts align with the organization’s overall brand positioning and campaign objectives. In addition, the authors urge tourism marketers to inspire Gen Zers through the use of slice-of-life ads such as getting over a breakup or celebrating graduation.

Wearable devices such as smartwatches, smart goggles and clothes can enrich Gen Zers travel planning and booking experience. For example, hotels can generate digital room keys for guests’ smart watches. Room service menu can be displayed in augmented reality. Artificial intelligence (AI) applications should be used to analyse individual user behaviour and detect the best times and messages to target travellers with highly-relevant marketing messages. Furthermore, travel and tourism businesses and marketers should find ways to fit into Gen Zers’ short attention span through providing technology-enabled efficiency solutions in their travel experience.

In their effort to address how to successfully connect with Gen Zers,Seemiller and Grace (2016) suggested a number of strategies such as: Being transparent as Gen Zers are “realistic problem solvers who appreciate honesty and authenticity from those who lead them” (193), making time to face time with them, understand the importance and influence that family and their parents play in their lives, make healthy food options the norm, and ensure an inclusive and affirming environment.Bielamowicz (2018) noted that since Gen Zers do not tend to be brand loyal, an effective way that companies could implement to increase their exposure would be by getting Gen Zers to act as their brand advocates. So, the author encouraged marketers to create content that feels fun, contemporary, and relevant. Also, the author suggested that they can build credibility and trust by leveraging influencers and vloggers - meaning people who regularly post short videos on - Instagram, YouTube, and Snapchat.

Building on these ideas, the authors are suggesting the following summarized strategies that travel and tourism marketers and industry professionals should implement to cater to Gen Z:

Create highly-targeted and personalized genuine content on mobile applications and online media platforms.

Create affordable packaged deals since this generation is on a budget and loves deals.

Create innovative apps that add real and new value to users that include but not limited to comparing, searching for a wide range of information and easily booking travel experiences.

Include more local people and local culture as part of the tourism package.

Include Gen Zers themselves in their staff to help other employees become familiar with this generation’s wants and needs.

Promote travel as a lifestyle and an experience instead of promoting flight plus hotel packages.

Carefully select, recruit and manage influencers such as vloggers (i.e., video bloggers), streamers and celebrities to promote their brands.

Encourage customers to post content of their experiences publicly.

Enable the maximum personalization of experiences and pay close attention to details.

Consider creating 3-D virtual tours, augmented reality and video clips of products, services and destinations as this generation is so much more visual.

Tailor tourism products by incorporating more activities that will have a larger and stronger social media presence.

Taking into consideration all the previously mentioned implications for the industry, one major contradiction still holds true: Gen Zers are young and budget-cautious target segment and travel is expensive. Therefore, travel and tourism providers must think of operational methods and approaches to adjust their pricing strategies and, in this case, offer their products and services at attractive prices, offering value for money. These could include: special packages offered during low/offseason, real-time price alerts, group discounts, reward points, etc.

Gen Zers tend to use innovative mobile applications and websites to compare and plan the travel, and then go to large travel booking websites such as Expedia to make the actual booking, simply because they offer the best prices. Start-up travel service providers should design, develop, and create packages that are tailored to the needs of this new generation of travellers and are based on affordable and unbeatable prices that would make it quite hard for large agencies and brands to compete with. It is also fundamental for those service providers to provide a clear justification of the set travel package prices, probably by offering a breakdown of costs, so travellers will be able to fully understand the benefits and value they receive for the money they spend. Furthermore, what Gen Zers would truly appreciate would be to have the ability to make any desired changes by adding or removing certain travel activities in order to reduce the price or adjust it to their standards. Therefore, travel and tourism marketers are strongly encouraged to carefully address these issues as by doing so they would not only increase their profits, but also attract and secure happy and satisfied loyal customers.

It is important for travel and tourism marketers to pay attention to Gen Zers’ low levels of patience, strong need for speed and instant results, along with the fact that they are so clear on what and how they want it, it is beyond doubt that Gen Zers will immediately move on to check another competitor on their electronic devices, if they are not impressed with a company’s available products or services or if its website is neither user-friendly or interactive. Therefore, it becomes apparent that well-organized strategic moves are needed in order to effectively approach, attract, and retain this new generation of young travellers.

CONCLUSIONS AND SUGGESTIONS FOR FUTURE RESEARCH

Generation Z is a new emerging market segment that has not received much attention and has remained quite unexplored compared to other generations such as Millennials. Generation Z is a very different generation with very unique qualities which is definitely bringing new changes in the world of travel and tourism which marketers must quickly adapt to and address. On top of that, new technological advances contribute significantly to new standards and avenues that come into play and, if used wisely, they can advance the quality of tourism marketing. This paper is among the first studies that focus on how to effectively address the needs of this new market segment and understand how to incorporate the new standards that the industry is facing through a careful revision of the buyer decision process model. The main purpose of this paper was to help marketers have a better understanding of the travel buying decision-making process of this new generation and how they operate in order to be able to adjust their marketing strategies and policies accordingly.

This study consists of the first step in that direction. However, further research is needed to investigate and bridge the gap of how the needs and expectations can be best met and how hospitality and tourism marketers can benefit from that. More thorough research is needed on the actual behaviour and habits of this new market segment, (e.g. how often they travel, what they value most, what their preferred social platform is, what their ideal type of travel is, etc.), which will be focused on specific parts of the hospitality and tourism industry (resorts, cruise lines, etc.), and will hopefully provide more concrete information on how those marketers can tailor their policies and organizational culture to Gen Zers’ needs. Future research should also place more emphasis on the post-booking evaluation stage of Gen Zers to discover how their travel experience impacts their post-booking evaluation and what would get them to become repeat guests/passengers/ cruisers/travellers. Another exciting area of research would be conducting a cross-cultural study comparing Gen Zers as travellers from different backgrounds, nations or cultures. That would be extremely valuable especially for those companies that expand and operate on an international level.