INTRODUCTION

Tourists travel for many different reasons. The desire to experience the natural environment and the opportunity to partake in different activities in nature are the main reasons given by many tourists for travelling to a destination (Kim, Lee, Uysal, Kim and Ahn 2015). Increasingly, contemporary tourists tend to seek increasingly active, healthier, more meaningful and more attractive ways to spend their time in destinations. The question of tourist motivation has been studied previously (Dann 1981;Baloglu and Uysal 1996,Uysal and Jurowski 1994,Plog 2001,Simková and Jindrich 2014, among others) as has the motivation of tourists to stay in nature and enjoy its beauties of nature and landscape (Kim et al. 2015;Mehmetoglu and Normann 2013;Pan and Ryan 2007;Said and Maryono 2018). However, there is currently no consensus on the most important motivational factors for visiting destinations among tourists generally motivated by natural beauty and landscape.

Official statistics also show that natural beauty and the landscape are important motives for many tourists. For example, in 2015, nature-based tourism accounted for 20% of international travel (Rainforest Alliance 2017, 19). Further, according to Eurostat (Flash Eurobarometer 432, 2016), in 2015, nature (including mountains, lakes and landscapes) was one of the two main motivations for travel for 32% of European travellers. Then, 45% European travellers reported that natural features (landscape, weather conditions, etc.) were what enticed them to return to a destination. Natural beauty is also an important motive for tourists’ arrival in Croatia. According to theInstitute for tourism (2020), spending a holiday in Croatia is the dominant reason (for 91% of the total number of tourists) for visiting Croatian destinations. Of a total of fourteen motives for coming to holiday tourism, nature was the leading one for 31.7% of visitors coming to continental Croatia. In addition, nature only trails the sea as the most important motive for as many as 56.2% of visitors coming to Adriatic Croatia (Institute for Tourism 2020).

It seems likely that spending time in nature is an important motive for travel during the post-pandemic period as well. The COVID-19 crisis has brought about significant changes in tourist behaviour patterns. Tourists show preferences for less crowded and nature-oriented destinations, with a preference for touristic activities that allow enjoyment of nature and the outdoors (Marques Santos et al. 2020).

Tourists expect to have diverse and unique experiences while travelling that will enrich them and that they will remember for an extended period. Memorable and long-lasting experiences are crucial for their future decision-making (Kim, Ritchie and Tung 2010). Because tourism is inherently experience-based (Kim 2017), and only unforgettable or memorable experiences affect tourists’ satisfaction and their post-consumption behavioural intentions (Wei, Zhao, Zhang and Huang 2019), it is important for marketing managers to develop preconditions for tourists motivated by the beauty of nature and landscape to experience surroundings that create such memories. A sustainable strategy for achieving and preserving a destination’s competitive advantage therefore must incorporate unforgettable experiences for tourists (Sthapit 2017;Yu, Chang and Ramanpong 2019).

Over the last decade, research has linked the tourist experience to memorability, focusing on different dimensions of memorable tourist experience (MTE) (Kim 2010;Tung and Ritchie 2011;Kim, Ritchie and McCormick 2012;Kim 2014;Chandralal and Valenzuela 2015;de Freitas Coelho and de Sevilha Gosling 2018;Kim and Chen 2020), as well on the relationship between MTE and behavioural intention or tourists’ decision making (Kim and Ritchie 2014;Mahdzar 2018;Tsai 2016;Zhong, Busser and Baloglu 2017;Kim 2017;Sthapit 2017;Huang, Zhang and Quan 2019;Sharma and Nyak 2019;Piramanayagam, Sud and Seal 2020;Chen, Cheng and Kim 2020). Although MTEs are receiving increasing attention, there been little work examining the interconnections among MTEs, tourist satisfaction and tourist behavioural intentions in nature-based tourism (Yu, Chang and Ramanpong 2019) for those tourists motivated by beauty of nature and landscape. Researchers (Kim, Ritchie and McCormick 2012,Kim and Ritchie 2014) have called for more studies to test the MTE scale in different contexts and in new samples.Kirillova et al. (2014) stressed that tourists’ interaction with and experience of a destination’s overall environment might affect their overall trip satisfaction. Hence, this study examines the key dimensions of MTE that affect satisfaction with the vacation experience of tourists motivated by the beauty of nature and landscape and the impact of satisfaction with vacation experience on behavioural intentions. Unlike other studies conducted in specific settings, this study focuses on MTE of tourists motivated by natural beauty and landscape, regardless of setting.

Based on previous, a research question is set: What is the relationship among the dimensions of MTE, tourist satisfaction, and behavioural intentions? This study aims to contribute to the theory of tourism experience by providing useful insights on the relationship among the dimensions of MTE, tourist satisfaction and behavioural intentions. Furthermore, the study develops and empirically tests a conceptual model that incorporates these dimensions for tourists motivated by beauty of nature and landscape. Focusing on tourists whose primary motive for vacation is the desire to visit a natural attraction, this study sheds light on the process by which satisfaction with the vacation experience can be created and how behavioural intentions are expressed in nature-based tourism.

From a practical point of view, the results of this study can help marketers establish marketing strategies that account for the impact of different dimensions of MTE on tourists’ satisfaction, which in turn will result in memorable and unforgettable tourism experiences.

This paper is divided into four sections. Following the introduction, the second section provides an overview of previous work regarding MTE, tourist satisfaction and behavioural intentions. The third part gives the research methodology and interprets the research results. The conclusion provides a synthesis of the entire paper, explains the limitations, and suggests further research directions.

1. THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

1.1. Concept of memorable tourism experience

Memorability is a crucial element in tourist experience studies. The most important source of information in consumer decision-making process is previous experience with products or services (Kim 2017). Positive experience that is remembered and stored in a consumer’s memory may be a significant predictor for future behavioural intentions (Larsen 2007;Hung, Lee and Huang 2014). In concepts, it is important to note that “memory” is a more general term than “memorable” (Sthapit and Björk, 2017;Sthapit 2017): memory is associated with the ordinary or mundane (Sthapit 2017), but something memorable is something special and enjoyable that people will talk about in the future (Zhong, Busser and Baloglu 2017). This term also refers to unforgettable or extraordinary things (Sthapit and Björk 2017). MTE, therefore, is “highly self-centred and considered a special subjective event in one’s life that is stored in a long-term memory as a part of autobiographical memory” (Kim and Chen 2018, 637).

There are two main types of MTE dimension: 1) those related to destination attributes and 2) those related to personal or psychological factors (Wei, Zhao, Zhang and Huang 2019). Research on MTE has not consistently differentiated these, using dimensions that overlap these aspects (Tung and Ritchie 2011,Kim, Ritchie and McCormick 2012,Kim 2014,Chandralal and Valenzuela 2015,de Freitas Coelho and de Sevilha Gosling 2018). Each study presents a modified classification and approach, but all agree that MTE is a significant predictor for behavioural intentions (Zhang, Wu and Buhalis 2018;de Freitas Coelho and de Sevilha Gosling 2018;Chen, Cheng and Kim 2020).

The current study adoptsKim, Ritchie and McCormick’s (2012) scale, as it is the most commonly cited, and it has been successfully validated and found reliable for assessing tourists’ memorable experiences (Kim 2017;Sharma and Nayak 2019;Yu, Chang and Ramanpong 2019). Its dimensions are hedonism, novelty, local culture, refreshment, meaningfulness, involvement and knowledge. Each of these seven dimensions is presented below.

Hedonism in tourism experiences is designated as “pleasurable feelings that excite oneself” (Coudounaris and Sthapit 2017, 1085). As pleasure seekers, tourists seek excitement and enjoyment while consuming tourism products and services (Yu, Chang and Ramanpong 2019). In nature-based settings, tourists combine various nature-based activities (including climbing, mountain biking, kayaking and hiking) to pursue hedonistic experience (Vespestad and Lindberg 2011). Novelty is the tendency to approach novel experiences (Wei, Zhao, Zhang and Hunag 2019). A novel tourist experience is a new, unusual or unique experience connected to the individual’s travel motivation (Coudounaris and Sthapit 2017). Tourists, as novelty seekers, travel to experience thrill, a change from routine and surprise and to alleviate boredom (Lee, Chang and Chen 2011). In nature based-tourism, novelty-seeking motivations have four factors: novelty learning, adventure, relaxation, and boredom relief (Kitouna and Kim 2017). An important motivation for travelling is experiencing local culture (Yu, Chang and Ramanpong 2019). Interacting with local people, tourists increase their understanding of local culture and make their travel experience more memorable (Kim 2010;Kim, Ritchie and McCormick 2012). Tourism attractions (such as heritage) and local food are relevant because they represent the culture of the destination, including tradition and way of life.

Refreshment, as relaxation and renewal (Zhong, Busser and Baloglu 2017), is one of the most important motivational factors for travel (Sthapit, 2017). In nature-based settings,Pan and Ryan (2007) identified relaxation as the main push factor motivating travelling. Following travel experience, “people feel happier, healthier and more relaxed” (Sthapit 2017, 5). The feeling of being relaxed significantly influences the memorability of an experience (Kim 2010). Meaningfulness can be explained as a generator of human personal development and change, including learning about oneself and society, maintaining good relationships with others, etc. (Coudounaris and Sthapit 2017). Tourists seek meaningful experiences to enable personal growth and self-development (Yu, Chang and Ramanpong 2019). They also seek unique experiences related to pleasurable emotions, meaningfulness and memories (Chen and Chen 2010). Nature-based tourists may obtain meaningful experience when learning about an ecosystem, participating in the conservation of natural resources or connecting with local communities (Kim, Lee, Uysal, Kim and Ahn 2015). In the literature on leisure and tourism, involvement is defined as the “degree of interest in an activity and the affective response associated with it” (Manfredo 1989). Active participation or engagement in various activities leads to memorable tourism experiences (Coudounaris and Sthapit 2017). Knowledge (the educational dimension of tourist experience) is related to developing new insights and skills (Kim 2016;Kim and Ritchie 2014). Self-education, which improves knowledge and skills, is a key motivational factor in travel to areas of historical and cultural importance.

Tourists motivated by the beauty of nature and landscape form meaningful experience through active participation or engagement in different activities while interacting with the environment. The MTE scale captures important dimensions of the experience affecting tourists’ memory. Our study builds on the following MTE dimensions: hedonism, novelty, local culture, refreshment, meaningfulness, involvement and knowledge, as identified byKim, Ritchie and McCormick (2012).

1.2. Tourist satisfaction and behavioural intentions

The ways that MTE affects behavioural intentions in different experiencescapes have been studied (Kim and Ritchie 2014;Kim 2017;Zhong, Busser and Baloglu 2017;Chen and Rahman 2018;Yu, Chang and Ramanpong 2019;Piramanayagam, Sud and Seal 2020). For example,Kim and Ritchie (2014) validated the MTE scale on a sample of Taiwanese tourists and found that all of its dimensions positively influenced tourist behavioural intentions (i.e. revisit and recommend the destination).Kim (2017) found that MTE is the most influential determinant for behavioural intention.Chen and Rahman (2018) showed that in cultural tourism, MTE affects tourists’ loyalty and intention to revisit cultural tourist destinations.Yu, Chang and Ramanpong (2019) showed a positive relationship among MTE, word-of-mouth and revisit intentions in nature-based tourism.Piramanayagam, Sud and Seal (2020) found that local food experience is a significant predictor for MTE, which in turn positively affects tourists’ revisit intention.

Satisfaction is a fundamental concept in the tourism marketing literature and represents an antecedent of behavioural intentions (Yoon and Uysal 2005). Tourist satisfaction is defined as “the sum of psychological states that arise from the consumption of tourism experiences” (Oliver 1997 in Kim 2017, 4). When actual experiences are equal to or better than expectations, tourist satisfaction is enhanced (Piramanayagam, Sud and Seal 2020). Satisfaction has a positive effect on (re)visits, revenue and image (Chen and Chen 2010;Antón, Camarero and Laguna-García 2017).

Researchers on leisure and tourism have reported that tourist satisfaction is a precursor for behavioural intention, understood as “the subjective tendency of tourists to take certain actions after participating in a tourist activity and evaluating the overall experience derived” (Tsai 2016, 539). These actions may include revisiting tourist destinations and recommending them to others, sharing experiences and post-purchase behaviours. A positive relationship has been found between tourist satisfaction and revisit intention, recommendation intention and sharing experiences with others (Jang and Feng 2007;Tapar, Dhaigude and Jawed 2017;Buonincontri, Morvillo, Okumus and van Niekerk 2017;Zhong, Busser and Baloglu 2017;Sharma and Nayak 2019;Antón, Camarero and García 2019;Piramanayagam, Sud and Seal 2020).

Measuring behavioural intentions is effective for predicting future tourist behaviour (Piramanayagam, Sud and Seal 2020), where revisit and recommendation intention are the most used measures (Chen, Cheng and Kim 2020). Recommendation behaviour is psychological behaviour that stimulates others to use what the customer likes (Chen, Cheng and Kim 2020). In the tourism literature, this is characterised as positive verbal recommendations to others (e.g. family and friends) after travel to a destination (Prayag, Hosany, Muskat and Del Chiappa 2017). Informal online experience sharing represents the creation and sharing of audio-visual content including knowledge-related information, emotions, imaginations and fantasies on vacation features (Munar and Jacobsen 2014). Tourists share content online in real time to only a small group or to all web users. Storytelling behaviour is a specific means of sharing experience. In tourism, recommendation intention is usually equated with a positive assessment of a product or service, but storytelling shares tourist experience with spatial and temporal characteristics (Tussyadiah and Fesenmaier, 2008).Zhong, Busser and Baloglu (2017) indicated that MTE can drive tourists to elaborate their positive tourist experience via storytelling (e.g. words and photos), going beyond merely recommending a destination. The recommendation of a destination or tourist experience implies a positive attitude and the persuasive communication of an experience, while sharing experience may not mean positive recommendation.

Breiby and Slåtten (2018) found that overall tourist satisfaction has a direct influence on three types of loyalty: intention to recommend the location to others, to revisit the location and to visit similar locations.O’Neill, Riscinto-Kozub and Van Hyfte (2010) confirmed the positive impact of the overall quality of a nature-based camping experience on overall satisfaction and on intent to revisit and/or recommend the tourism provider. MTE significantly influences behavioural intentions. However, to our knowledge, there has been little research that explores the relationship between the dimensions of MTE and satisfaction of tourists motivated by beauty of nature and landscape.

2. HYPOTHESIS DEVELOPMENT AND MODEL SPECIFICATION

Researchers have studied the importance of the relationship between MTE and tourist satisfaction.Tung and Ritchie (2011) proposed a positive relationship between the two.Ali, Ryu and Hussain (2016) observed creative tourist experience and its impact on memories and satisfaction, indicating a relationship among the three concepts.Kim (2017) found that MTE significantly enhances tourist satisfaction.Sharma and Nayak (2019), in the context of yoga tourism, andAnggraeni (2019), in the context of nature-based village tourism, observed that MTE significantly improves the level of tourist satisfaction. Thus, the following hypothesis is proposed:

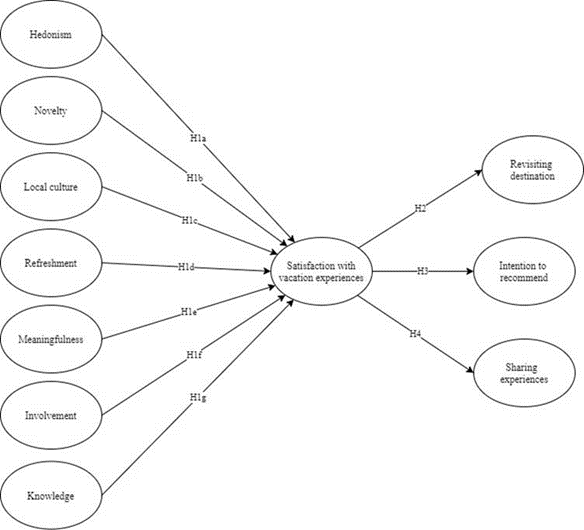

H1: MTE positively influences satisfaction with vacation experience.

To determine the impact of particular dimensions of MTE on satisfaction with tourist experience, we developed seven sub-hypotheses.

Duman and Mattila (2005) considered hedonism to be essential for determining tourist satisfaction. Moreover,Rodríguez-Campo, Braña-Rey, Alén-González and Fraiz-Brea (2019) found that hedonism is a significant predictor of tourist satisfaction.Triantafillidou and Petala (2015) found out that the hedonic dimension is an essential predictor of tourist satisfaction in nature-based tourism. Therefore, we posit that:

H1a: Hedonism positively influences satisfaction with vacation experience.

Novelty is significantly related to tourist satisfaction (Sthapit 2017).Lee, Chang and Chen (2011) found that the novelty of a package tour is a relevant predictor for tourist satisfaction. Moreover,Kitouna and Kim (2017) showed that novelty learning, and adventure significantly affect tourist satisfaction. Therefore, we set the following hypothesis:

H1b: Novelty positively influences satisfaction with vacation experience.

The dimensions of MTE have the greatest impact on overall satisfaction with the summer vacation experience.Lončarić, Dlačić and Perišić Prodan (2018) indicated that local culture has the highest impact on satisfaction. Moreover,Piramanayagam, Sud and Seal (2020) found that the local food experiencescape positively affects memorability of experiences, which makes tourists more satisfied. Hence, we propose that:

H1c: Local culture positively influences satisfaction with vacation experience.

Researchers have reported a relationship between refreshment (i.e. relaxation) and satisfaction.Pan and Ryan (2007) contended that only attributes generating a sense of relaxation have a statistically significant effect on overall tourist satisfaction in a visit to a forest park. Hence, we posit that:

H1d: Refreshment positively influences satisfaction with vacation experience.

Ali, Ryu and Hussain (2016) observed that tourists with pleasant memories of creative experiences (i.e. meaningful feelings) are more satisfied, which would affects their behavioural intentions. Therefore, we set that:

H1e: Meaningfulness positively influences satisfaction with vacation experience.

Gohary et al. (2020) studied the impact of MTEs on destination satisfaction, revisit intentions and tourists’ positive word-of-mouth in Iranian eco-tourism. They found that involvement is a significant predictor of destination satisfaction among Iranian eco-tourists. Therefore, we propose that:

H1f: Involvement positively influences satisfaction with vacation experience.

Chen and Chen (2010) showed that the educational dimension of visitor experience in heritage tourism is positively related to tourist satisfaction by increasing perceived value. Similarly,Song, Lee, Park, Hwang and Reisinger (2014) revealed that educational experience is an essential predictor of functional value, which influences traveller satisfaction.Gohary et al. (2020) determined that knowledge impacts destination satisfaction in eco-tourism. Hence, we posit that:

H1g: Knowledge positively influences satisfaction with vacation experience.

The positive effect of tourist satisfaction on revisit intention has been established (Yoon and Uysal 2005;da Costa Mendes, Oom do Valle, Guerreiro and Silva 2010;Kim, Woo and Uysal, 2015;Tapar, Dhaigude and Jawed 2017). Further,Kim, Woo and Uysal (2015) found that a high degree of satisfaction with leisure experience leads to greater revisit intention. Therefore, we posit that:

H2: Satisfaction with vacation experience positively influences revisit intention.

It has been shown (Hosany and Witham 2010;Antón, Camarero and Laguna-García 2014;Prayag, Hosany, Muskat and Del Chiappa 2017;Sotiriadias 2017; El-Said and Aziz 2019) that tourist satisfaction is a direct antecedent for recommendation intention or positive word-of-mouth behaviour.Prayag, Hosany, Muskat and Del Chiappa (2017) found that satisfaction is a significant predictor of recommendation intention for island destinations.Sotiriadis (2017) examined the relationship between travellers’ experiences in nature-based attractions and their post-consumption behaviours. They found that satisfaction has increased influence on word-of-mouth intention. Hence, we state:

H3: Satisfaction with vacation experience positively influences recommendation intention.

Present-day tourist experiences are largely shared using information technology.Chung, Tyan and Chung (2017, 7) suggest that satisfaction with travel experience can be considered to be an “integration of the interaction and reflection among tourists themselves, places they visit, other tourists, and social networks”.Sotriadias (2017) found that satisfied tourists who are satisfied are willing to share their experiences with others and recommend (in offline and online reviews) the service provider. Therefore, we propose that:

H4: Satisfaction with vacation experience positively influences tourists’ sharing of experience.

We propose a conceptual model to supplement these hypotheses inFigure 1.

3. METHODOLOGY

A survey was conducted in a sample of citizens of the Republic of Croatia who had taken leisure trips domestically, elsewhere in Europe or outside Europe that had included an overnight stay within 12 months prior to taking the survey. Of the surveys collected, those that indicated that the respondent had travelled in the past year with motive to visit destination because of beauty of nature and landscape were retained. Data were collected from November 2017 to January 2018 on a sample of tourists who are attracted to the destination by the beauties of nature and landscape. A structured questionnaire and the paper and pencil method were used to collect data.

In the each of the two Croatian statistical regions (Official Gazette, NN 96/2012), 600 surveys were disseminated. Data collectors were instructed to attain as near as possible to gender parity. In all, 943 questionnaires were returned, with a total of 921 usable responses (451 from continental and 464 in coastal Croatia, with 6 missing this information). In total, 51.5% surveys were completed by women and 48.5% by men nearly matching the gender structure of Croatia as a whole (Croatian Bureau of Statistics 2017). The age structure of the respondents differed somewhat from the structure indicated by the Croatian Bureau of Statistics: 83.7% of the respondents were younger than 49 years, while according to government data, 70% of travellers in 2017 were younger than 49 (Croatian Bureau of Statistics 2017), this can be attributed to the greater propensity of younger people to participate in the survey. Of the 921 questionnaires collected, 334 were used for further analysis (170 from continental and 162 from coastal Croatia, with 2 missing this information) because they indicated that beauty of nature and landscape was a primary travel motive.

Data were collected on the socio-demographic profiles of the respondents and the characteristics of their travel (destinations, travel organisations, accommodations, nights spent, companions and previous visits). The questionnaire incorporated items from previous studies that measured constructs. For memorable tourism experience, we used an MTE scale borrowed fromKim, Ritchie and McCormick (2012) that included hedonism, novelty, local culture, refreshment, meaningfulness, involvement and knowledge. The respondents were asked to evaluate their experience in the destination where they were staying on a scale of 1 (“I have experienced nothing”) to 7 (“I have experienced very much”). All other constructs were measured on a 5-point Likert-type scale, anchored at 1 “strongly disagree” and 5 “strongly agree”. Satisfaction with the vacation experience was borrowed from Prebensen, Kim and Uysal (2015), intention to recommend was measured using the scale fromKim, Chua, Lee, Boo and Han (2015), and the scale ofKim, Woo and Uysal (2015) was used to explore revisit intention. Sharing of experience was measured usingBuonincontri, Morvillo, Okumus and Van Niekerk’s (2017) scale.

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the pattern and characteristics of travel using SPSS ver 26. The hypotheses were empirically tested by partial least square structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM) using the program SmartPLS 3.0.

4. FINDINGS

Descriptive data on the sample and travel characteristics are given here, along with the results of the measurement and structural model, are presented.

4.1. Sample characteristics

The sample description and travel characteristics of the travellers whose primary motive for travelling was beauty of nature and landscape are shown inTable 1.

Source: Research results

Most respondents were women (57.8%) aged from 18 to 25 years (32.3%) and from 26 to 35 years (29.9%), with a university degree (44.3%), travelling in European countries (53.6%), having organised the trip independently (77%), staying in private accommodation (32.3%) for 4 to 7 overnight stays (39.8%), travelling with a partner (36.2%) and visiting the destination for the first time (62%).

4.2. Measurement model

A variance-based PLS-SEM technique was used to test the hypotheses. PLS-SEM is preferred when the objective of the study is theory development and prediction and explanation (Hair, Hult, Ringle and Sarstedt 2014, 14). Further, PLS-SEM is “a promising method that offers vast potential for SEM researchers, especially in the marketing and management information systems disciplines” (Hair, Ringle and Sarstedt 2011).Mateos-Aparicio (2011) emphasises PLS-path modelling as an important research tool for the social sciences, especially in satisfaction studies. Taking the objectives of this study into account, PLS-SEM is appropriate.

Use of PLS-SEM is performed in two steps. First, the validity and reliability of the measurement model are evaluated. The structural model is then assessed, and the hypotheses are tested. The model assessment was performed following the recommendations defined byHair, Ringle and Sarstedt (2011) andHair, Hult, Ringle and Sarstedt (2014).

Using the program SmartPLS 3.0, we first examined the measurement model followed by the structural model. The PLS-SEM results for the measurement model are presented inTable 2.

Note: * All factor loadings were significant at p < .001; CR stands for composite reliability; AVE stands for average variance extracted

Source: Research results

Table 2 indicates that the coefficients of all item loadings for the reflective constructs ranged from 0.712 to 0.939 and therefore exceeded the recommended threshold value of 0.708 (Hair, Hult, Ringle and Sarstedt 2014, 103). Further, all item loadings were significant at the 0.001 level, as established by the bootstrapping method. Internal consistency reliability was also confirmed because the composite reliability values, ranging from 0.851 to 0.936, were greater than 0.70, as recommended by (Hair, Ringle and Sarstedt 2011). Convergent validity was confirmed by the average variance extracted (AVE) of each construct which was well above the cut-off of 0.50 (Hair, Hult, Ringle and Sarstedt 2014).

Discriminant validity was assessed using the Fornell-Larcker criterion (Table 3) and the heterotrait-monotrait ratio of correlations (HTMT).

Source: Research results

Table 3 shows that the square roots of the AVE values for all constructs were above the construct’s highest correlation, with other latent variables in the model. Further, all HTMT values were lower than 0.9 (Henseler, Ringle and Sarstedt 2015), ranging from 0.224 to 0.866. The results confirm the discriminant validity of the measurement model. Thus, it met all the necessary criteria, and the assessment of the structural model and the verification of the set hypotheses was begun.

4.3. Structural model

An essential step in assessing the inner model is calculating the path coefficients and significance levels, as doing this allows researchers to establish support for or reject the proposed hypotheses. To evaluate the structural model and check the set hypotheses, we calculated the standardised path coefficients and significance levels (Table 4).

Source: own study.

The analysis showed that H1b, H1c H1e and H1g were not supported because the path coefficients were not significant. All other coefficients were significant, and all other hypotheses were supported.

The R2 value obtained for Satisfaction with Vacation Experience was 0.428, indicating that the model explains a moderate amount of the variance (42.8%) in tourist Satisfaction with Vacation Experience. The R2 value for Intention to Recommend was also moderate (0.596), but the values for Intention to Revisit (0.299) and Sharing Experience (0.169) were weak, according to the standards ofHair, Ringle and Sarstedt 2011.

The construct Satisfaction with Vacation Experience had a Q2 value of 0.240; Intention to Recommend had 0.466; Intention to Revisit had 0.167; and Sharing Experience had 0.094. It is evident that all values were larger than zero, which indicated that the exogenous constructs had predictive relevance for the endogenous constructs under consideration (Hair, Ringle and Sarstedt 2011).

DISCUSSION OF FINDINGS

This study examined the impact of MTE dimensions for satisfaction with the vacation experience of tourists motivated by the beauty of nature and landscape. Of the seven dimensions of the MTE scale (Kim, Ritchie and McCormick, 2012), only hedonism, refreshment and involvement showed a direct positive impact on satisfaction with vacation experience. This confirms the work ofZhong, Busser and Baloglu (2017), who showed that those three dimensions are the prominent characteristics of MTE.

Our results found the greatest impact on satisfaction of tourists motivated by the beauty of nature and landscape in hedonism, which supportsTriantafillidou and Petala (2015), who indicated that the hedonic dimension of sea-based adventure experiences is an essential predictor for tourist satisfaction. Similarly,Duman and Mattila (2005) andRodríguez-Campo, Braña-Rey, Alén-González and Fraiz-Brea (2020) indicated that hedonism is essential for achieving satisfaction with the vacation experience. It is logical to conclude that if tourists seeking exciting experiences and enjoying their travels realise their expectations, they will be satisfied.

This study further indicates that refreshment has a positive effect on satisfaction with vacation experience. Tourists seek to relax during their trip and feel rejuvenated upon returning from it. Enjoying nature and beautiful landscapes makes this possible.Pan and Ryan (2007) indicate that relaxation among visitors to forest parks affects their overall satisfaction.Yu, Chang and Ramanpong (2019) also found that refreshment is the most prominent dimension of MTE, which significantly influences the recommendation intentions.

It was found that tourists motivated by the beauty of nature who participate in the activities they desire and visit the places they plan to achieve a higher level of satisfaction. This study thus confirmed previous findings (Kim, Woo and Uysal 2015) indicating that tourists’ involvement is important for achieving their satisfaction. Additionally,Yu, Chang and Ramanpong (2019) indicated that involvement is related to nature-based tourists as a significant dimension of memorable experience that positively affects tourists’ revisit intention. This can result in the conclusion that a high level of involvement could be crucial for achieving tourists’ satisfaction with their vacation experience.

Finally, a significant positive relationship was established between satisfaction with vacation experience and behavioural intentions. Satisfied travellers were found to be more prone to revisit and recommend the destination/experience, which is consistent with the findings of several previous studies (e.g. Kim, Woo and Uysal 2015;Tapar, Dhaigude and Jawed 2017;Prayag, Hosany, Muskat and Del Chiappa 2017). Additionally, a weak but positive impact was found between satisfaction with vacation experience and sharing the experience with family, relatives and friends. Our findings are consistent with those ofSotiriadis (2017), who found that visitors who are more satisfied with their vacation are more likely to share their experience, both offline and online.Zhong, Busser and Baloglu (2017) found that MTE is a significant predictor for tourists’ storytelling behaviour as a special form of eWOM communication or narrative. They suggested that storytelling behaviour should be encouraged in the virtual world because it affects travel decision-making.

CONCLUSION AND IMPLICATIONS

The findings of this study provide valuable insights into the relationships among MTE, tourist satisfaction and behavioural intentions. This study contributes to the theory of tourism experience, providing insight into the relationships among memorable tourism experience, satisfaction and behavioural intentions and empirically testing them on a sample of tourists motivated by the beauty of nature and landscape. It distinguishes the influence of different dimensions of memorable tourism experience on satisfaction with vacation experience, indicating the importance of focusing on hedonism, refreshment and involvement. It indicates that all three lead to the behavioural consequences intention to recommend, revisit intention and sharing of experiences, which are important for tourists motivated by beauty of nature and landscape.

Furthermore, the results obtained indicative and can help marketing managers develop strategies to promote unforgettable experience by prioritising hedonism, refreshment and involvement. In their communication materials, web pages and social media, they could provide information on a destination’s attractions, produce information packets related to specific natural attractions to enable visitors to have sufficient details to plan their visit or vacation. Because hedonism is about indulging and having exciting experiences, this could be used to design activities with a specific goal, such as wine routes, food routes, historic monuments and routes, battle sites or nature park routes. In these routes, providing additional value is related to immersing the senses in the experience, such as by providing wine or food tasing spots, allowing travellers to hand-pick ingredients for their meals, cooking with locals or taking part in local events. Furthermore, the sense of refreshment could be achieved by providing glamping campsites in nature or close to nature parks and overnight experiences in hobbit houses or tree houses in harmony with nature where visitors can peacefully spend their vacation and enjoy nature. In these places, they could spend the night under the starry sky and listen to the birds in the early morning. Marketers could also focus on tourists’ involvement by providing opportunities for activities in which tourists could participate, such as feeding birds or helping villagers with their cattle or in their gardens. Visitors could be provided with opportunities to create their own experiences of nature, such as in hiking or cycling tours. This could imply the co-creation of experiences, as service providers and tourists can jointly create their experiences through social media, storytelling or collaboration to select a specific destination and activities at that destination. Following the COVID-19 crisis, travellers will likely look for less-developed coastal and countryside destinations, national parks and nature reserves (Spalding, Burke and Fyall 2020). This could present an opportunity for those promoting such destinations. It is necessary to work on special programs that focus on nature and biodiversity, with more intensive promotion of green and healthy destinations in which tourists are provided with an unforgettable experience to motivate them to return.

This study had some limitations. It focused only on Croatian citizens, and its results may have been influenced by specific aspects of the Croatian population. Future research in this area could seek an international respondent population. Additionally, respondents were classified according to their desire to visit a natural attraction as the primary motive for their vacation. It would be interesting to determine whether tourists who were motivated to explore different tourist experiences in a destination would express their behavioural intentions differently. Further research could focus on specific nature-based tourism contexts and explore additional motives or activities. This study focused on tourists who had travelled somewhere with an overnight stay in the previous year, so it relied on respondents’ memory and previous experience. The results might have been different if the respondents had been approached in situ after experiencing an activity related to natural beauty and landscape. It would be interesting to focus on specific groups of tourists that experience different forms of nature-based tourism to examine their specifics related to MTEs, if those existed. This could aid marketing managers focusing on specific tourist market niches. Additionally, further research could include scales and variables specific to individuals who care particularly about the environment, such as the level of environmental friendliness, green values, green behaviour and environmental awareness. Also, exploring the mediating effect of customer satisfaction between MTE dimensions and behavioural dimensions could bring new perspective that should be included in further research. It would be interesting to research the moderating effect of generation to see whether there are differences among Baby Boomers, Generation X, Generation Y and Gen Z in specific tourism contexts. Another useful suggestion for future research would relate to the use of a qualitative method (e.g. a focus group or in-depth interview) that would provide additional insight into memorable tourism experience and the behaviour of nature-based tourists, especially in niche tourist markets.