INTRODUCTION

Hospitableness, though not easy to explain in specific terms, generally refers to the attributes of people who tend to willingly embrace guests and create a good environment for them without any financial expectation or exchange (Gehrels 2019;Lashley 2015;Tasci and Semrad 2016). Hospitableness is considered the most substantial component of the hospitality experience for consumers, with a critical role in experiential consumption and memorable experiences (Tasci and Semrad 2016). Researchers identified the contribution of hospitableness to the experiential consumption in different types of accommodation and argued that commercial establishments with an added dimension of hospitableness are more successful in enriching memorable guest experiences than those offered in the sharing economy (Mody, Suess and Lehto 2019). Similarly, the importance of hospitableness is accepted in the food and service industry (Meyer 2008;Pezzotti 2011;Tomasella and Ali 2019) and considered as a differentiating tool with the potential to create and enhance competitive performance (Golubovskaya, Robinson and Solnet 2017;Ford and Heaton 2001;Lashley 2008;Lashley and Chibili, 2018;Ponsonby-Mccabe and Boyle 2006), and to positively affect the behavioral intentions such as consumer satisfaction and brand loyalty in the long term (Ariffin, Nameghi and Zakaria 2013;Golubovskaya et al. 2017;Mody et al. 2019;Teng 2011).

Hospitableness is the most dynamic, prominent, and influential component of hospitality, and the essential element of human interaction between hosts and guests. It is a culturally defined concept (Tasci and Semrad 2016) and cultures have a distinct understanding of hospitableness (Gehrels 2019). Considering that culture is influential on many consumer behavior variables, the perception of hospitableness is likely to be highly influenced by culture. Nonetheless, very few studies empirically assessed this core element of hospitality (e.g.,Tasci and Semrad,2016) and cultural differences in hospitableness have not been empirically documented thus far.

This study provides insights into potential cultural matches and clashes in the concept of hospitableness in a destination context. To demonstrate the influence of culture, the current study investigated Turkish hospitableness in the destination context by following a mixed-method approach guided by the realist paradigm. Since destinations use their hospitable locals as a pull factor, understanding the differences in hospitableness is important for meeting host and guest expectations. While most previous studies investigated hospitableness and hospitality at a firm-level or service context, the current study focused on hospitableness in the destination context due to the critical role of hospitableness for the competitive advantage of destinations. Even though hospitableness is closely linked to host personality at the individual level, this individual-level hospitableness culminates into collective hospitableness at the community level. Based on the perceived hospitableness of individuals from a culture, potential travelers have a perceived level of hospitableness for the entire host community from that culture. The current study’s focus is on the perceived collective hospitableness at the community level in Turkish culture.

1. LITERATURE REVIEW

1.1. Hospitality and Hospitableness

In tourism and hospitality literature, hospitality is evaluated along a continuum, where commercial hospitality and altruistic hospitality form the opposite ends (Lashley 2000;Heuman 2005). Commercial hospitality can be used tactically by service organizations to manage relationships with employees, consumers, and other stakeholders (Lugosi 2017). Commercial hospitality, ideally embedded into the organizational culture of an establishment, should be aligned with the acknowledgment of hospitality by the cultural norms and values of the societies constructing its internal and external stakeholders (Lombarts 2018). Altruistic hospitality, on the other hand, indicates the willingness to be hospitable without any expectation of compensation or reciprocity (Lashley 2015, 1). A few studies investigated hospitality in service establishments, mostly in accommodation outlets’ execution of commercial hospitality (Brotherton 1999;Hemmington 2007;Ariffin 2013) where the monetary exchange between hosts and guests raise guest expectations and force service providers to comply with operational standards and systems (Ramdhony and D’Annunzio-Green, 2018).

Recently,Tasci and Semrad (2016) explained the relationship between hospitality and hospitableness in a layered structure, where the layers of hospitality encompass sustenance products, entertainment products, and services surmounted by hospitableness. Hospitableness, in this layered structure, implies the interaction between product/service providers and consumers, hence emphasizing the importance of a human component of hospitality. Since hospitality is an umbrella concept that goes beyond the consumption frame involving “more than a service encounter” (Lashley, Morrison and Randall 2005), hospitableness, may be instrumental during all phases of consumption and result in building loyal customers as “commercial friends” (Lashley and Morrison 2003). Therefore,Lashley (2007) recommends a good understanding of hospitality and hospitableness to build long-term relationships with consumers since “successful hosts are able to engage customers on an emotional and personal level, which creates feelings of friendship and loyalty amongst guests” (p. 223).

Hospitableness is considered as a key to developing a sustainable competitive strategy dependent upon time, space, and sociocultural elements (Ariffin et al. 2013;Brotherton 1999;Chan, Shaffer and Snape 2004;King 1995;Lashley 2007). Hospitableness may be more significant in the extremely changeable environment where human capital dimensions such as experience, skills, and behavior count more for the success of companies and brands, including destination brands (Denizci and Tasci 2010;Lashley 2007;Pringle and Kroll, 1997;Wright, McMahan and McWilliams 1994). Furthermore, consumers’ focus on hedonic or emotional dimensions of experience in today’s service economies (Holbrook and Hirschman, 1982;Oh, Fiore and Jeoung, 2007;Pine and Gilmore 1998,1999;Schmitt 1999;Smilansky 2009) may render hospitableness as the most important element of the memorable experiences for consumers (Ariffin et al. 2013). Hospitableness is found to influence consumer satisfaction (Ariffin et al. 2013;Teng 2011), which is a close correlate of consumer loyalty and other positive outcomes. With such potential, most studies measured hospitableness and hospitality at the firm level while only a few measured the construct in the destination context.Tasci and Semrad (2016) measured hospitableness in two firm-level contexts (i.e., restaurant and hotel) and a destination context to generate a scale applicable to different levels.

1.2. Dimensions of Hospitableness

Different dimensions of hospitableness have been proposed and tested in past research. Some studies endeavored this by coining a different terminology. For example,Medema and de Zwaan (2020) used the concept of ‘hostmanship’ in their qualitative research and found that genuine actions and connections between hosts and guests are the pivotal elements of transmitting the feeling of welcome, while being restricted by operational systems and protocols are considered the main obstacles in achieving hostmanship in commercial environments.Blain and Lashley (2014) identified hospitableness as an act of generosity initiated by a desire to welcome and be hospitable to strangers. Focusing on the motives of altruistic behavior in individuals, the authors developed the scale of hospitableness consisting of the factors: the desire to prioritize guests before oneself, to make them happy and feel special.Golubovskaya et al. (2017) investigated how one understands hospitality and how this understanding leads to hospitable behavior from the perspective of hotel employees and argued that most participants in their research lacked the ability to describe hospitality and to differentiate it from service provision. Adding to this confusion, researchers also have a tendency to use hospitality and hospitableness interchangeably. For example,Ariffin and Maghzi (2012) identified the dimensions of hospitality as personalization, warm welcoming, special relationship, straight from the heart, and comfort.Pijls, Groen, Galetzka and Pruyn (2017) introduced a new scale measuring the experience of hospitality with three dimensions, namely, inviting, care, and comfort.Beldona, Kher, and Bernard (2020) summarized guests’ emotional outcomes of hospitality as feeling welcomed, accepted, invited, cared for, appreciated, worthy, significant, honored, respected, and valued. These dimensions are more about the hospitable service provision rather than the general concept of hospitality.

In a scale development study,Tasci and Semrad (2016) pictured hospitality as a conglomerate concept with several layers, hospitableness being the outer layer that defines true hospitality. They defined hospitableness as “the positive attitudinal, behavioral, and personality characteristics of the hosts that result in positive emotional responses in guests feeling welcomed, wanted, cared for, safe, and important” (p. 31) and operationalized it as a three-dimensional construct with heart-warming, heart-assuring, and heart-soothing factors in the American culture. This scale relies on the basis that the positive attitude, behavior, and personality traits of providers lead to guests’ emotional responses in feeling wanted, cared for, welcomed, safe and important, and involves three dimensions. Recognizing the cultural influences,Tasci and Semrad (2016) recommended retesting their 24-item scale in different cultures; however, cultural differences in hospitableness has not been substantiated with empirical data thus far.

1.3. Cultural Influences on Hospitableness

Culture is an important constituent shaping both the performance and reception of hospitableness. The impact of culture on the host or guest perceptions is acknowledged in the existing literature (Boylu, Tasci and Gartner 2009;Brown and Osman 2017;Reisinger and Turner 2002;Tasci and Boylu 2010;Tasci and Severt 2017). Some studies also delved into the impact of culture on hospitality or hospitableness since cultural norms and values are expected to be related to understanding and practices of hospitableness in different societies (Shyrock 2002;Clark and Cahir 2008;Griffiths and Sharpley 2012). With the concept of ‘hospitality life politics,’Lynch (2017) referred to the hospitality acts of individuals in their search for security and trust every day. The author argued that the hospitality practiced by individuals facilitates welcoming, hence healthy, hospitable societies, and further added that there is a need to investigate hospitality from the lenses of the cultural interpretations of the terms; welcome and non-welcome, in different societies.Sharpley (2014) argued that during the commercial-based interaction between tourists and service providers, so-called a liminal tourism culture is created, meaning that both parties may temporarily suspend their cultural expectations, prejudices, and behaviors, resulting in disguised true feelings and attitudes toward each other in a mutually beneficial encounter. Furthermore,Yick, Köseoğlu, and King (2020) referred to different service provision practices by hotel employees according to the nationality and cultural background of guests.

From the perspective of Greek culture,Christou (2018) looked into the broad notion of love as part of a philoxenia, a Greek mythology-driven phenomenon, characterized by ‘friendliness’ and ‘love for others.’ He investigated how tourists are offered and express love for people, places, and societies in Cyprus. In this research, tourists associated certain gestures and attitudes with love, including welcoming and friendliness, acceptance and kindness, politeness, helpfulness, and, the display of positive emotions and expressions. The obstacles in receiving the notion of love, in the meantime, are linked by tourists to such factors as displaying negative emotions, antisocial behavior, lack of professionalism or enthusiasm, impoliteness, inappropriate and racist behavior from service providers or locals. In a later study,Christou and Sharpley (2019) differentiated the commercialized term ‘hospitality’ from ‘philoxenia’ and explored the understanding and change of the phenomena in time from the perspective of rural tourism stakeholders in Cyprus. Their qualitative study indicated that philoxenia, a concept strongly tied to the Greek and Cypriot cultures, is perceived as genuine tangible and intangible offerings without expecting anything in return, enriched with providers’ psychological support to guests. While the philoxenia attitude is part of the local identity of people, who are born into a society where philoxenia is accepted as a cultural norm, rural destinations are found as ideal environments for the guest experience of philoxenia. They implied that economic crises, changing tourist profiles (self-centered and materialistic guests), increased tourism-related crime rates, and modernization are the contemporary challenges threatening philoxenia.

From a different cultural context,Heuman (2005) also tested whether different tourism forms result in varying hospitability practices in his qualitative research exploring tourists’ experiences in Dominica. The study looked into protection, reciprocity, obedience, and performance as elements of hospitality from the perspectives of tourists and presented that limited monetary reciprocities between tourists and locals lead to different practices of hospitality.

The current study aimed to investigate what hospitableness means in Turkish culture, an Eastern culture thatTasci and Semrad (2016) suspected to display differences from the Western counterparts. Turkish people are identified by Hofstede’s (2011) Eastern culture dimensions of uncertainty avoidance collectivism, and high power distance (Tasci and Severt 2016) as opposed to American culture, a Western individualistic culture (Buda and Elsayed-Elkhouly 1998) that likely no longer support the requirement to be hospitable as they maybe did earlier (Gehrels 2019). Turkish hospitableness is rooted in hospitality settled throughout the Silk Road since the 16th century (MacLaren, Young, and Lochrie 2013). Turkish hospitableness is conceived to cover sociability, care, generosity, and helpfulness (Cetin and Okumus 2018) and Turkish people as family-friendly, sociable, hospitable, and warm (Bohner, Siebler, González, Haye and Schmidt, 2008).Cetin and Okumus (2018) investigated the hospitality of Turkish people from the perspective of international visitors through a qualitative study, which distinguished commercial hospitality offered at tourism establishments from local traditional hospitality denoting unconditional attitudes and behavior of local people toward tourists outside the commercial servicescape of the sector. They revealed four main elements of Turkish hospitality, namely, sociability, care, helpfulness, and generosity. The authors noted that hospitality has always been a reminiscent element of the country’s culture throughout its history and the reciprocity in offering genuine hospitality relates to the locals’ pride in hosting. Therefore, the current study is expected to provide a different portrait of hospitableness in the Turkish cultural context.

2. METHODOLOGY

A mixed-method was used in data collection since the cultural context requires the best of both constructivist and positivist approaches to identify the nuances and intricacies of the highly cultural concept of hospitableness and commonalities across different cultures. Thus, a realist approach was adopted; a previously tested scale of hospitableness was adopted to identify commonalities and the scale was supplemented with open-ended questions to capture the differences and nuances. Thus,Tasci and Semrad’s (2016) scale of hospitableness was complemented with several open-ended questions to investigate the hospitableness of the locals of destinations from travelers’ perspectives. Following their recommendation,Tasci and Semrad’s (2016) original 24-item scale (first column inTable 2) rather than the refined 10-item scale (i.e., Welcoming, Courteous, Respectful, Kind, Trustworthy, Honest, Reliable, Generous, Sociable, and Open-minded) was used to test in Turkish culture. To identify the cultural nuances of hospitableness for Turkish people, open-ended questions inquired 1) besides the list, what other additional characteristics make the locals of a destination hospitable; 2) which previously visited destinations have the most hospitable locals and most important characteristics that made these locals most hospitable; 3) which previously visited destinations have the least hospitable locals and most important characteristics that made these locals least hospitable.

An online survey was developed using Qualtrics. Both the 24-item scale of hospitableness and open-ended questions were included in the survey. Hospitableness scale items were back-translated to assure accurate capture of the meaning in the Turkish language. The scale was designed with 7-point importance anchors (1=very unimportant, 7=very important) and respondents were asked to rate the importance of these characteristics for them to consider the locals of a destination as hospitable. Besides the hospitableness scale items and open-ended questions, sociodemographic and past trip behavior-related questions were also included to describe the acquired sample.

The first study was conducted with an online sample of 20 respondents who rated the hospitableness scale items and answer open-ended questions to capture the differences in Turkish hospitableness. Based on the responses, some items fromTasci and Semrad’s (2016) scale were consolidated; specifically, six items (i.e., kind/polite, honest/sincere, consistent/reliable) were reduced to three items to avoid redundancy in Turkish, leaving 21 distinct scale items. Additionally, the analysis of the responses to the open-ended questions revealed five new items reflecting the uniqueness of Turkish culture (i.e., patient, not insisting, free of prejudice, tolerant, and generous-hearted - gönlü bol in Turkish-) to be added to the scale, revealing a 26-item scale in total. After these consolidations and additions, the 26-item scale was tested for reliability and validity in the second study. Using this modified 26-item scale of hospitableness, the second study was conducted with another online sample of 307 respondents.

IBM’s SPSS software version 24 and SmartPLS 3.0. were used to purify the scale. Principal Component Analysis (hereafter PCA) was conducted using SPSS 24 while Confirmatory Factor Analysis (hereafter CFA) was conducted through Partial Least Squares-CFA (PLS-CFA) using SmartPLS 3.0. PLS is an appropriate CFA technique with small samples as well as for testing new theories where the validity of new concepts is explored (Sarstedt, Ringle and Hair 2014). Using SmartPLS 3.0, a two-step process was used to assess the item loadings (outer model) and the predictive power of factors of hospitableness (inner model) using 2000 bootstrap resamples and the confidence intervals at 95% (Hair, Hult, Ringle and Sarstedt 2013).

The descriptives were inspected for central tendencies. Then, data were randomly split into two, one to conduct PCA and one to conduct CFA, by following the practice recommended by the previous research on scale development (e.g.,Costello and Osborne 2005;Gerbing and Hamilton 1996;Henson and Roberts 2006;Tasci and Semrad 2016;Worthington and Whittaker 2006). Since a split-sample method was used, PCA for extraction followed by Varimax Rotation with Kaiser Normalization was deemed an appropriate technique of identifying the underlying pattern or dimensions of hospitableness in the data. Factors identified in PCA were subjected to CFA for validation of the hospitableness dimensions.

Several indices were used to assess factor reliability and validity. For factor reliability or stability, both Cronbach’s Alpha and composite reliability (CR) were used. A Cronbach’s alpha score of 0.70 is suggested as the threshold (Hair, Black, Babin and Anderson 2010) a value of 0.60 is also deemed acceptable (Sekaran and Bougie 2016). Composite reliability (CR) greater than .6 was used (Bagozzi and Kimmel 1995;Fornell and Larcker 1981;Gaskin 2012;Hair et al. 2010). Convergent validity was assessed through three indices: 1) significant factor loadings of the items on the factors; factor loadings greater than .6 indicated convergent validity (Bagozzi and Yi 1988;Clark-Carter 1997;Cole 1987); 2) the predictive power of each item on its factor using t-tests; a factor loading significantly at the .01 level displays convergent validity by a significant contribution of the item to the factor (Anderson and Gerbing 1988;Marsh and Grayson 1995;Netemeyer, Boles and McMurrian 1996); 3) Average Variance Extracted (AVE) for each factor; convergent validity is assumed when CR > AVE and AVE > 0.5 (Fornell and Larcker 1981;Gaskin 2012;Hair et al. 2010).

Discriminant validity was assessed through two indices:1) the inter-item correlations among the variables; inter-correlations between two variables that are smaller than .85 are considered as an acceptable level of discriminant validity of the measurement scale (Kline 2005); 2) Maximum Shared Variance (MSV), Average Shared Variance (ASV) and Average Variance Extracted (AVE) for each factor, discriminant validity is assumed when MSV < AVE and ASV < AVE (Gaskin 2012;Hair et al. 2010;Fornell and Larcker 1981).

3. FINDINGS

3.1. Sample Characteristics

As can be seen inTable 1, respondents were 31 years old, on average, 52.5% female and 47.5% male, residing in several different cities in Turkey. The majority (64%) of the respondents were single, while 31.8% of them were married. The majority (77.9%) of the respondents had a college/university degree, with an average annual income of about 29K TL. They are frequent travelers, the majority having two to six out-of-town trips per year.

3.2. Descriptives and PCA Results of the Hospitableness Scale Items

Table 2 displays the hospitableness scale items, rated between 5.05 and 6.64, on average. The highest-rated items are respectful (M=6.64), trustworthy (M=6.63), and honest (M=6.51) while the lowest-rated items are social (M=5.32), courteous (M=5.15), and generous (M=5.05). The newly generated items, tolerant (M=6.32), free-of-prejudice (M=6.20), not insisting (M=6.17), patient (M=5.69), and generous-hearted or gönlü bol in Turkish (M=5.47) were not in the top or bottom three.

| Original items generated in the American context byTasci & Semrad (2017) | The modified version of items used in Turkish context in the current study |

Turkish version of the items used in the current study 1=Very unimportant, 7=Very Important | Min. | Max. | Mean | St. Dev. |

| Kind* | Kind/polite | Kibar/nazik davranan | 2 | 7 | 6.45 | .893 |

| Polite | (same as kind in the Turkish context) | |||||

| Happy | Happy/smiling | Mutlu /güler yüzlü | 3 | 7 | 6.41 | .856 |

| Sincere | Honest/Sincere | Dürüst | 3 | 7 | 6.51 | .872 |

| Honest* | (same as sincere in the Turkish context) | |||||

| Flexible | Flexible | Duruma uygun davranan/esnek | 1 | 7 | 5.54 | 1.216 |

| Helpful | Helpful | Yardımsever | 1 | 7 | 6.33 | .928 |

| Friendly | Friendly/genuine | İçten | 1 | 7 | 6.12 | 1.117 |

| Sociable* | Sociable | Sosyal | 1 | 7 | 5.32 | 1.325 |

| Attentive | Attentive | Yaptığı işe özen gösteren | 2 | 7 | 6.39 | .891 |

| Courteous* | Courteous | Hürmetkâr** | 1 | 7 | 5.15 | 1.558 |

| Generous* | Generous | Cömert | 1 | 7 | 5.05 | 1.466 |

| Consistent | Consistent/reliable | Tutarlı** | 1 | 7 | 6.13 | 1.237 |

| Reliable* | (same as consistent in the Turkish context) | |||||

| Welcoming* | Welcoming | Konukları hoş karşılayan | 1 | 7 | 6.38 | .919 |

| Personable | Personable/warm | Cana yakın/sıcak kanlı | 1 | 7 | 6.03 | 1.131 |

| Respectful* | Respectful | Saygılı** | 2 | 7 | 6.64 | .726 |

| Trustworthy* | Trustworthy | Güvenilir | 1 | 7 | 6.63 | .779 |

| Professional | Professional | İşinin ehli | 1 | 7 | 5.84 | 1.363 |

| Considerate | Considerate/ empathizing | Halden anlayan/ empati kuran | 1 | 7 | 6.04 | 1.163 |

| Well-groomed | well-groomed | Kişisel bakıma dikkat eden | 1 | 7 | 5.78 | 1.330 |

| Open-minded* | Open-minded | Açık görüşlü | 1 | 7 | 5.80 | 1.325 |

| Accommodating | Accommodating/ understanding | Uyumlu | 1 | 7 | 5.75 | 1.242 |

| Dedicated to service | Serving | Hizmetkar** | 1 | 7 | 5.46 | 1.449 |

| Newly added items in the Turkish context | ||||||

| Patient | Sabırlı | 1 | 7 | 5.69 | 1.271 | |

| Not insisting/ harassing | Özgür bırakan/ısrarcı olmayan** | 1 | 7 | 6.17 | 1.072 | |

| Free of prejudice | Ön yargısız | 1 | 7 | 6.20 | 1.156 | |

| Tolerant | Hoş görülü** | 3 | 7 | 6.32 | .926 | |

| Generous-hearted | Gönlü bol** | 1 | 7 | 5.47 | 1.431 |

*: The final scale items remained after scale refining inTasci and Semrad’s (2016) study

**: Deleted in PLS-CFA for low factor loadings.

Using randomly sampled 150 cases of the data, PCA was applied to the 26 hospitableness items to derive fewer, more meaningful, and uncorrelated factors. Factors with eigenvalues exceeding one were kept since those represent the variance equal to or more than that of the average original variable. The initial factors were rotated using Varimax with Kaiser Normalization. Variables with loadings closer to one have a good correlation with the factor on which they load; those with substantial loadings, equal to or greater than 0.5, are considered as significant (Hair et al. 2010) and thus, are used to represent the factors. The results of the analysis are provided inTable 3.

All 26 items were substantially loaded onto six factors, with no cross-loadings, explaining 64% of the original variables in the data. The computation for internal stability revealed high values of Cronbach’s alpha coefficient: α=0.87 for Factor I, α=0.81 for Factor II, α=0.75 for Factor III, α=0.74 for Factor IV, α=0.72 for Factor V, and α=0.60 for Factor VI. Since a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.60 is considered substantially stable (Sekaran & Bougie, 2016), these factors are considered stable with substantially high internal consistency. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy was 0.831 and Bartlett's Test of Sphericity was significant at p<.01. KMO scores close to or above 0.7 are considered a good indication that correlation patterns are relatively compact and factor analysis should yield distinct and reliable factors.

*: Deleted in PLS-CFA for low factor loadings. Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy=.831 Bartlett's Test of Sphericity=.000 Extraction Method: Principal Component Analysis. Rotation Method: Varimax with Kaiser Normalization.

Variable loadings that are greater than 0.50 are considered significant enough from a practical viewpoint to remain within a factor (Hair et al. 2010). Individual items showed a good correlation with the extracted factors and were all readily interpretable. Only one item, courteous loaded slightly lower than 0.50, but kept in the PCA factor solution since it was only a slight difference. A close examination of the factor items reveals a detailed picture of hospitableness with different dimensions addressing different aspects of hospitableness in Turkish culture.

Factor I is named Lenience since it includes the positive host characteristics and attitudes (i.e., tolerant (new item), free of prejudice (new item), open-minded, accommodating, patient (new item), not insisting or harassing (new item), generous-hearted (new item, gönlü bol in Turkish), considerate) all of which may result in a sense of relief and freedom in respondents. All five of the new items were included in this factor, which also explained the highest variance of the original variables. Factor II is named Compassion since it includes those positive host characteristics and attitudes (i.e., generous, social, flexible, consistent), fostering a feeling of understanding and empathy. Factor III is named Proficiency since it included job-related host characteristics and attitudes (i.e., professional, well-groomed, attentive, and respectful) that have the potential to create confidence in guests. Factor IV is named Grace since it included the general host characteristics and attitudes (i.e., helpful, serving, friendly, personable, and courteous) that may charm guests. Factor V is named Civility since it included the general kind-hearted host characteristics and attitudes (i.e., kind/polite, welcoming, happy) that welcome guests. Factor VI is named Veracity since it included the host characteristics and attitudes (i.e., trustworthy and honest) that induce the feeling of safety and security in guests. The grand means are 5.94 for Factor I, 5.50 for Factor II, 6.16 for Factor III, 5.86 for Factor IV, 6.45 for Factor V, and 6.52 for Factor VI. These grand means show that the Veracity dimension of hospitableness is the most important followed by Civility, Proficiency, Lenience, Grace, and Compassion.

3.3. Results of PLS-CFA

3.3.1.Measurement model (Outer Model)

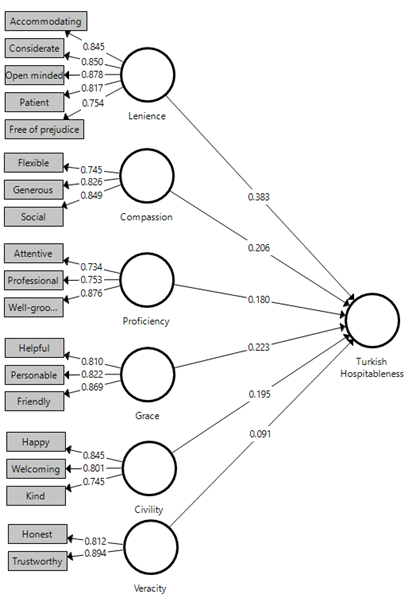

Using the remaining 157 cases in the sample, PLS-CFA was applied on the 6-Factor model of hospitableness with all 26 items to check the reliability and validity of constructs. Construct reliability and convergent validity were evaluated by several measures including factor loadings, Cronbach’s Alphas, composite reliability (CR), and AVE scores (average variance extracted) (Hair et al. 2013). As marked inTable 2, seven items, three of which are the new items (not insisting, tolerant, and generous-hearted or gönlü bol in Turkish) were deleted in PLS for loadings lower than 0.7 (Hair et al. 2013).Table 4 reflects the factor loadings and cross-loadings; all remaining 19 items loaded substantially (i.e., 0.7 or more) onto the respective six factors and lower than 0.7 onto the others.Figure 1 also displays factor loadings of scale items to their respective factors and standardized beta values.

Table 5 displays the construct reliability and validity of the measures. The Cronbach’s Alphas and Composite Reliability (CR) of all factors were above the threshold of 0.60. Besides, all AVEs were above 0.5, indicating the convergent validity of the factors. These values confirmed the scale’s convergent validity for measuring the 6-dimensional measurement model of the hospitableness construct. The discriminant validity of the model was checked by comparing the square root of the AVE of the factors to the inter-correlations. As displayed inTable 5, the square roots of the AVE, shown on the diagonals, were greater than the correlations between the factors, shown as the off-diagonal elements, confirming the discriminant validity of the 6-dimensional measurement model of the hospitableness construct in the Turkish cultural context.

* :Square root of average variance extracted Figures below the AVE line are the correlations between the factors.

3.3.2. Structural model (Inner Model)

The structural model (inner model) was assessed using 2000 bootstrap resamples and the confidence intervals at 95%.Table 6 displays the structural estimations. The significance of the path coefficients, between the individual dimensions and the hospitableness construct was evaluated for the relative importance. All paths were significant at α < 0.01 (Table 6). Standardized beta values reflect that Lenience has the highest contribution (β=0.383, t=18,201, p<.01) followed by Grace (β=0.223, t=14.258, p<.01), Compassion (β=0.206, t=14.975, p<.01), Civility (β=0.195, t=8.116, p<.01), Proficiency (β=0.180, t=8.625, p<.01), and Veracity (β=0.091, t=4.395, p<.01). As can be seen, this order is different from the order of Factors based on the percent of variance explained and based on factor grand means. The importance of a construct dimension is not readily evident in either of these indices.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

This study endeavored to investigate what hospitableness means in Turkish culture by applyingTasci and Semrad’s (2016) Hospitableness Scale supplemented with open-ended questions inquiring about hospitableness in the general destination context. The sample acquired online was representative of the young, single, and educated segment of the target population; however, their tendency to be well-traveled reflects the appropriateness of the group in defining the concept of hospitableness for the benefit of the tourism industry. The study revealed a more intricate picture of the hospitableness concept in Turkish culture compared to a rather simple version in the American culture. Open-ended questions revealed several additional items, some of which cannot be even directly translated into English (e.g., generous-hearted or gönlü bol in Turkish).

Findings showed that the sample rated hospitableness scale items above the mid-point on the 7-point scale, between 5.05 and 6.64, on average. The highest-rated items were respectful (M=6.64), trustworthy (M=6.63), and honest (M=6.51). This shows both differences and similarities with the findings ofTasci and Semrad (2016), who revealed that the American sample’s highest-rated items were “‘polite’ (6.28), ‘helpful’ (6.26), and ‘respectful’ (6.17)” (p. 36). This result implies that, regardless of the cultural nuances, being respectful may be one of the most important attributes of hospitableness, a universally important aspect of human interaction. However, while the respectful item remained stable in both PCA and CFA procedures as an aspect of the heartwarming dimension of hospitableness that explained the highest variance of the original data ofTasci and Semrad (2016), in the current study, it was part of the Proficiency dimension but not stable and thus deleted in CFA. This result does not necessarily mean a lack of its importance; respectfulness may be taken for granted for hospitableness in general, rather than being an aspect of underlying dimensions in some cultures.

On the other hand, results show that trustworthiness and honesty are the other most critical aspects of hospitableness for Turkish people while politeness and helpfulness are for the American culture. This heightened importance of trustworthiness and honesty (with high item ratings and highest factor grand mean) in Turkish culture implies the tendency of being alert in cultures of developing economies for some potentially undesirable behavior. On the other hand, the heightened importance is on the more indicative aspects of polite and helpful in the developed economy culture (i.e. American in this case) where well-established tourism and hospitality regulations may have eliminated the locals’ chances of taking advantage of the visitors and thus general public’s level of alertness. Another explanation might be hidden in the impact of culture on consumption habits and on the relationship between service providers and consumers. According toHofstede’s (2011) cultural dimensions, in collectivist cultures, as in Turkey, people tend to consult other group members before making decisions and value emotional and behavioral control of the purchasing process (De Mooij 2010). Trust established between a consumer and a service provider, therefore, comforts them about their ‘right decision’, as opposed to individualistic countries, as in America, where consumers often take independent, hence quick and impulsive purchasing decisions, the process of which is enriched by the variety of service providers (Hosfstede and Minkov 2010).

The study revealed that the lowest-rated items were social (M=5.32), courteous (M=5.15), and generous (M=5.05), while Tasci and Semrad revealed the lowest-rated items to be ‘open-minded’ (5.10), ‘well-groomed’ (5.08), and ‘generous’ (4.87). This finding is different from those ofCetin and Okumus (2018) who identified generosity as one of the main elements of Turkish hospitableness. In both American and Turkish cultures, generosity is of the lowest importance, which implies hospitableness interpreted by the respondents in commercial hospitality where serving sizes and portions are typically standardized as opposed to domestic hospitality where a serving of refreshments is guided by hosts’ generosity.

Three of the original items ofTasci and Semrad (2016) were consolidated with other items due to semantic limitations where the direct translations revealed the same meaning, thus respondents stated redundancy. On the other hand, five new items were suggested to account for the cultural nuances of hospitableness in Turkish culture. These new items, namely tolerant (M=6.32), free-of-prejudice (M=6.20), not insisting (M=6.17), patient (M=5.69), and generous-hearted (M=5.47), were rated relatively high. Turkish society is made of several different ethnicities, nationalities, and cultures, thus, tolerance and lack of prejudice have traditionally been in teachings for good citizenship. Not insisting and patience have particular relevance to the tourism industry, where visitors sometimes feel harassed because of occasional hawkers encountered in tourist destinations. Generous-hearted, on the other hand, is a commonly known and valued characteristic of a person who is giving, caring, and pleasant all around. However, these five new attributes are not in the highest or lowest-rated categories. Additionally, even though all five of them loaded onto the Lenience factor that explained the majority of the variance in the original data, three of them, tolerant, not-insisting, and generous-hearted were dropped in the CFA procedures due to low factor loadings. These results imply a transition or change in the Turkish culture, fading of the cultural nuances that were traditionally more important but losing their critical roles in the contemporary society shaped by the popular culture and the new world values.

Nonetheless, both PCA and CFA procedures revealed a more detailed, complicated, and nuanced structure of the hospitableness concept in Turkish culture. WhileTasci and Semrad’s (2016) study revealed nine stable items loading onto three factors in American culture, the current study revealed 19 items loading onto six factors, lenience, grace, compassion, civility, proficiency, and veracity, with the level of contributions to Turkish hospitableness in that order. Hospitableness seems to have deeper and more intricate meanings in an Eastern culture than the Western counterpart. The complexity of Eastern cultures with deeply rooted meanings in concepts such as hospitableness may pose a challenge to the tourism industry where consumers and providers from many different cultures are involved in the co-creation of experiences. Thus, experienscapes (Pizam and Tasci 2019) in tourism need to include opportunities for all to learn and appreciate the cultural intricacies for a holistic and transformational experience for different stakeholders. While dealing with Turkish hosts and guests, lenience is of the utmost importance, for them to feel hospitableness, the interaction needs to be grounded in an open-minded, patient, considerate, accommodating, and prejudice-free attitude.

These cultural differences need to be carefully handled by the industry; education of both sides may be needed to avoid the cultural clash, disorientation, and even worsening prejudices. An inexperienced American tourist visiting Turkey may describe their cultural observations as unique or weird; on the other hand, an inexperienced Turkish tourist visiting the USA may feel a lack of hospitality or short-change, depending on how informed they were before the trip. This is especially important when guests may interact with the locals in their domestic hospitality setting.

In domestic hospitality, as opposed to commercial hospitality, the Turkish phrase “Tanri misafiri” (i.e., “guest from God”) used to describe especially stranger visitors -similar to the Indian principle of “Atithi Devo Bhava” (i.e., “the guest is God”) may manifest potentially extreme Eastern views on hospitableness from the perspective of an individualistic Western culture perspective. This difference can be seen in a daily behavior example: in American culture, inviting friends and family members to food and drinks using the phrase, “help yourself,” is considered hospitable; whereas serving food and drinks, and insisting when guests decline are still traditional practices in Turkish culture, especially in the eastern regions. Some level of influence of these cultural practices may still be expected in the way the food is served or help is offered in commercial hospitality in different cultures although despite widespread standards of global business practice. Cultural obligations on domestic hospitableness and commercial hospitableness may be mutually influential; even though commercial hospitableness with commercial standardization may not be governed by the same cultural obligations as those of domestic hospitableness, a hint of culture on commercial hospitableness may still be expected.

The influence of culture on commercial hospitality may not always be positive for a guest from another culture. In some collectivist cultures, the freedom to do as you wish in your own space is not always warranted despite high levels of hospitality in other dimensions. For example, in some Eastern regions of the world, it is a common practice to ask traveling couples for a marriage certificate to stay in the same hotel room, which then suggests that the guests, even if they pay, can only have the freedom to do whatever they wish within their own space when they are lawfully wed. This example captures the changing nature of both hospitality and hospitableness from one culture to another. Furthermore, hospitableness is a contemporary concept, constantly adapting to the changes in the environment. Thus, contemporary hospitableness, though difficult to conceptualize and measure, need to be monitored to gauge the direction of the shift in culture.

The study implies the shifting nature of sociocultural concepts in different cultural contexts. A scale developed to measure such a concept may be too narrow or too detailed in another culture. In this study, the hospitableness scale developed in the American culture was too narrow for Turkish culture and the extended scale in Turkish culture may be overly detailed in American culture. Thus, scales measuring highly socio-cultural concepts need to be validated in other cultures through rigorous scale development procedures before applying them in modeling for relationships among constructs. Otherwise, the identified relationships may not reflect the true nature of social phenomena. In other words, a strictly positivist approach to capturing sociocultural phenomena may fall short in providing a true explanation for the social phenomena; instead, a realist approach may provide a better representation of different realities in different cultures by supplementing the standard tools of positivism with the subjective views of constructivism.

The study retested a validated scale in measuring the hospitableness of the locals of a destination on an online sample with a relatively younger and more educated sample of Turkish respondents. Involving more of older and less educated respondents, particularly respondents from more rural areas may yield more intricacies with the signs of the deeper traditional view of what is Turkish hospitableness. Additionally, other product levels such as restaurant and hotel contexts may reveal different results depending on the depth of expected experiences as well as the level of commercialization and standardization in these contexts. Future studies may provide a more detailed picture of hospitableness in Turkish culture by comparing different product contexts as well as different groups. Also, the current study retested the hospitableness scale in an Eastern culture and compared it to the original scale findings in the American culture. The findings may be different in far eastern cultures as well as other western cultures. Futures studies need to retest the scale in other cultures in order to identify the globally valid dimensions of hospitableness as well as its intricacies in culturally different societies.

Furthermore, future studies can compare hospitableness in other contexts that can be generated based on Derrida’s discussions of conditional/unconditional hospitality and hosts’ and guests’ gains and losses (c.f. O’Gorman 2006). The benefits and costs of conditional and unconditional hospitality may exist in both private/domestic and public/commercial settings. This means that when guests are accepted unconditionally in a private hospitality setting, with no financial costs in this context, they still incur some psychological costs due to feeling indebted and perhaps even financial costs involved in some form of repayments such as a gift or an invite. Similar unconditional hospitality may be described in commercial hospitality settings where special guests are treated at no cost through loyalty or customer relationship programs. Although guests do not incur financial costs in this setting either, they are expected to feel similar indebted feelings and further repeat business in the future. In fact, conditional hospitality with all costs paid by the guests may bear minimum psychological costs on the guests in both domestic and commercial settings. Future studies may investigate if the expected hospitableness in these different settings is the same or different.

Finally, the study findings could be different if repeated today because of the global disturbance of human phenomena (perceptions, attitudes, and behavior) due to the Covid-19 pandemic that started at the onset of 2020 and has been waving across the globe for almost a year by the time of construction of this manuscript. With the heightened level of focus on safety and security, especially in the area of health, a universal change may have taken place where offerings and services for cleanliness and hygiene are becoming more and more important. A traditional Turkish host who has a much less personal space than that of an American host may be viewed as unhospitable when they attempt to offer candy and cologne coupled with a hug to a visitor. Instead, a host with a facial mask and offering hand sanitizers from an increased social distance may be the expected hospitableness of the Covid-19 reality. These restructured realities and perceptions merit replication of this study in Turkish culture as well as the original study byTasci and Semrad (2016) in American culture.