INTRODUCTION

Tourism is considered to be important in developed and developing economies. It contributes to the development of a country, region and destination. Moreover, the hospitality industry contributes to the tourism and travel sector with around 30% of economic impact (Statista.com 2018).This is partially because hotels and hotel chains in their business activities cooperate with a plethora of different organizations and companies. Like suppliers of different products and services needed for everyday operations, local and regional government and tourist boards on different levels, various tourist agencies and many other organizations and companies that help deliver the tourism product. Hence, they have economic impact on overall industry. As tourism industry is dynamic, doing business in such an environment urges hotels to be responsive to changes in the micro and macro environment. As companies that are developing relationships with their partners are able to respond more adequately to dynamic environmental changes (Gilli, Mazzanti and Nicolli 2013;Grbac and Lončarić 2005). This ability consequently improves their performance (Paik 1992).

When developing relationships with partners, companies consider different partners like suppliers, hotel guests, tourist agencies, tourist offices, employees and all other stakeholders that form organization’s network of partners. Hence, an organization builds its own network of partners (Grbac and Lončarić 2010) in order to respond adequately to dynamic environmental changes. Essential in these networks are long-term win-win relationships and joint creation of value between involved parties (Gummesson 1999, 24 inGummesson 2002). This characterizes relationship marketing. Relationships between networks of partners are considered as prosperous if relationship quality among partners is good (Athanasopoulou 2009). Hence, when exploring the relationships between partners in the hospitality industry a focus should also be on determining the quality of relationships among partners within a network.

Focus on relationship quality according to the relationship marketing literature (Athanasopoulou 2009) is a crucial for any organization that aims to develop a network of partners. Inherent to building quality relationships is approaching them from a long-term perspective (Jiang et al. 2016) and considering interaction with partners in the long run. These long-term relationships have influence on satisfaction with performance (Hoppner, Griffith and White 2015). Accordingly, this applies to the hospitality industry and hotels as well. As mentioned before a plethora of different partners form a network of a hotel company. Therefore, a development of relationships between hotel and networks of partners is important.Wu and Lu (2012) assert that CRM implementation and different relationship marketing practices oriented towards hotel guests influence different business performance in hotels and similarly relationship marketing influences customer loyalty among hotel guests (Narteh et al 2013). In addition, establishing relationships with their guests and implementation of customer relationship management practices can help hotels to enhance customer lifetime value through increasing relationship quality (Wu and Li 2011) in different types of hotels. Still, neglected perspective are the relationships between other types of partners like suppliers, tourist agencies, tourist offices and employees and their influence on hotel performance. Especially in the light ofKim and Cha (2002) work that points that high quality relationship improves willingness to stay in a relationship among hotel guests and due to the fact that long-term relationships as well as collaboration are contributing to perceived hotel performance (Ramayah, Lee and In 2011).

This paper aims to contribute to relationship marketing theory, especially in the hospitality industry. Yet, it remains unclear how building relationships among network of partners is reflected in hotel performance, especially when considering relationship quality. Hence, the purpose of this paper is to explore partner relationships and their influence on perceived hotel performance. The objectives are to explore how partner relationships can be evaluated through the lens of relationship quality and to examine the influence of partner relationships on perceived hotel performance approached from a financial and non-financial perspective.

The paper is structured as following. After the introduction, the theoretical background is provided on relationship quality and company performance in the context of relationship marketing. Then, a conceptual model is proposed and hypotheses are set. The methodology is explained and research results are presented. Lastly, the study’s contribution, managerial implications, limitations and ideas for further research are discussed.

1. LITERATURE REVIEW

Relationship quality is a concept widely accepted in theory and business. Still lacking, however, is a consensus about its definition and implementation. It is considered that relationship quality derives from relationship marketing.Grönroos (1996, 23) argues that relationship marketing focuses on long-term ‘relationships with customers and other stakeholders, at a profit, so that the objectives of all parties are met’, while Berry (1983 inHennig-Thurau and Hansen 2004) puts emphasis on retaining customers and enhancing relationships. In creating and building relationships it is important that all the partners involved consider the relationship as being valuable and beneficial to them (Danaher, Conroy and McColl-Kennedy 2008). Consequently, relationship quality emerges when relationships with partners are perceived as valuable and worth investing into.

Relationship quality is considered to be a multidimensional construct (Ulaga and Eggert 2006;De Wulf, Odekerken-Schröder and Iacobucci 2001) that is oriented towards building long-term relationships among partners and creating win-win outcomes for each partner included (Morgan and Hunt 1994). Others (Henning-Thurau and Klee 1997) argue that relationship quality considers cooperation, among partners in a network, aimed at satisfying needs and wants. Some (Crosby, Evans and Cowles 1990) even assert that relationship quality is built on confidence in a specific organization and its ability to provide satisfaction in relationships with partners. Therefore, not only cognitive elements but also emotions are present in quality relationships (Moliner, et al. 2007;Sánchez-Garcia et al. 2007). Although relationship quality is ambiguously approached (Hennig- Thurau 2000), several of its elements are continuously included in studies. These elements are trust, satisfaction and commitment (e.g.Garbarino and Johnson 1999;Ulagga and Eggert 2006;De Canniere, De Pelsmacker and Geuens 2009;Moliner et al. 2007).Athanasopoulou (2009) points out that those relationship quality dimensions are predominantly found in studies related to relationship quality. Relationship quality in the service and hospitality industries is also approached through commitment, trust and satisfaction (Baker, Simpson, and Siguaw 1999;Garbarino and Johnson 1999;Moliner et al. 2007;Beatson, Lings and Gudergan 2008;Ramayah, Lee and In 2011;Wu and Li 2011). Building on previous research, relationship quality is approached through its three elements: commitment, trust and satisfaction.

Commitment. When partners within a company network are willing to develop long-term relationships they start to express commitment toward others included in that network (Moorman, Zaltman and Deshpande 1992). Partners form network as they search for a reliable partner. This ensures an adequate groundwork for developing good quality and long-term relationships. The development of these relationships is successful when all engaged partners have a common goal that is realized throughout the collaboration.Morgan and Hunt (1994) stress that commitment develops on a positive attitude towards a partner in a relationship and on the ability to develop long-term mutual collaboration between the partners. Hence, commitment can be approached as “a lasting desire to maintain an appreciated relationship” (Moorman, Zaltman and Deshpande 1992, 316).

Partners maintain a relationship if it is important to them. With that in mindBowen and Shoemaker (1998, 15) assert that when partners in a network are committed to each other, they are willing to make short-term sacrifices to realize long-term benefits. Therefore, commitment emerges in a relationship that is valuable for all partners. It also includes intention to keep relationships with partners and develop them more profoundly in the future (Morgan and Hunt 1994). It includes emotions; the belief that it is more valuable to continue a relationship than to terminate it and the feeling of obligation towards a partner to sustain the relationship (Bansal, Irving and Taylor 2004). This is also present in hospitality and the airline sector (e.g.Pritchard, Havitz and Howard 1999), where commitment is found to be significant in enhancing customer loyalty. Also,Ramayah, Lee and In (2011) claim that commitment influences business performance through increasing collaboration among partners in tourism sector.

Trust among partners. The development of long-term relationships is based on trust among partners and trust is considered as necessary for long-term relationships (Bendapudi and Berry 1997). When trust is present among partners they are prepared to take additional risks, share gathered information on new market trends, be more tolerant towards others in a relationship and work over problems that occur during a business relationship (Moorman, Deshpande and Zaltman 1993;Morgan and Hunt 1994). Trust is defined as “one party’s belief that its needs will be fulfilled in the future by actions undertaken by the other party” (Anderson and Weitz 1989, 312). It exists if partners consider that service is reliable, has high integrity and partners have confidence in each other (Moorman, Zaltman and Deshpande 1992). Consequently, it reduces ambiguity in a relationship as partners have more belief in each other.

Trust is approached as an element that outlines the development of long-term relationships between partners. It is a result of given promises (Gronroos 1990). In the hospitality industry,Kim and Cha (2002) assert that trust, as an element of relationship quality, has a positive influence on decisions to continue a certain relationship in the future. Similarly, assertsNareth et al. (2013) that trust influences loyalty as well as relationship quality enhances different customer lifetime value metrics (Wu and Li 2011) as usage quantity, loyalty, word-of-mouth and purchase intention. Still evidence exists that trust has no effect on collaboration in tourism sector (Ramayah, Lee and In 2011). Therefore, trust is found to be important in relationships between partners in hospitality sector.

Satisfaction. Hotels need to retain old partners and acquire new ones. They need to focus on partners that are inclined to continue a relationship with them and ones that feel a company is providing them value (Berry and Parasuraman 1997). Furthermore, partners within network who are prone to stay and collaborate with organization are also more inclined to develop long-term relationships.Lam and Zhang (1999) assert that satisfaction is present when a product or service fulfils partners’ needs and wants. Satisfaction derives from the evaluation of a specific product or service and its comparison to possible alternatives that can also fulfil a specific need or desire (Shiv and Huber 2000).

Satisfaction can be approached from two viewpoints: the first focuses on single transactions and the second, on a cumulative approach (Wang and Lo 2003). This cumulative approach is prevalent when a company is building long-term relationships with partners within a network. Furthermore, long-term relationships are characterized by collaboration among partners and, consequently, by joint value creation (Gummesson 2002). However, the road from having satisfied to loyal partners is not straightforward. AsBennett and Rundle-Thiele (2004) contend, satisfaction does not simply translate into loyalty. This applies to the hospitality industry as well. In the hospitality industry there is a plethora of different partners, such as suppliers, tourist agencies, tourist boards, tour operators and others. Focusing on partners and managing relationships with them contributes to satisfaction and developing long-term relationships between a company and its partners in tourism sector (Wu and Li 2011;Kandampully and Suhartanto 2000;Sánchez-Rebull, Rudchenko and Martín, 2018). In addition, relationship quality, approached as consisting of trust and satisfaction, enhances relationship continuity in tourism (Kim and Cha 2002) and hospitality sector (Wu and Li 2011).

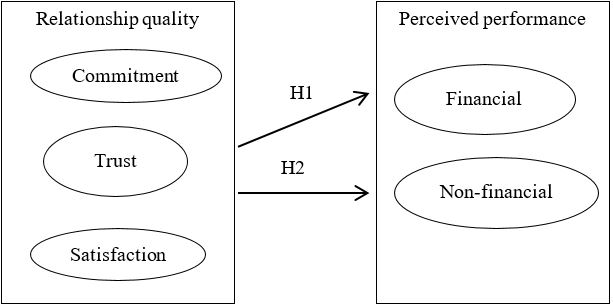

2. CONCEPTUAL MODEL AND HYPOTHESES DEVELOPMENT

Establishing high-level business performance results in the tourist market is challenging for many companies especially on the long-run. Due to fierce competition, emphasis is put on, among other things, achieving greater profitably, increasing average daily rate per room, and enlarging market share and sales growth. With aim to focus on performance hotels also develop relationships with different partners like suppliers, hotel guests, tourist agencies, tourist offices, employees. Collaboration and establishing long-term relationships with partners is closely related to relationship quality. When long-term relationships are considered to be of a high level they bring satisfaction to partners (Crosby, Evans and Cowles 1990). Also, partners that feel commitment (Ramayah, Lee and In 2011) and trust (Nareth et al. 2013) are more prone to stay in a relationship and continue collaboration with network of partners. Consequently, high satisfaction together with trust and commitment form high relationship quality. Close collaboration and establishing long-term relationships with partners will positively influence company performance (Sin et al. 2002;Huntley 2006) approached as sales growth, service sales growth, market share and ROI. Hotel performance is predominantly approached through these financial indicators (Mihalič, Knežević Cveblar and Žabkar 2014). Therefore, it is to be expected that high relationship quality among partners will also have a positive influence on a hotels’ financial performance.

Therefore, we posit:

H1: Relationship quality positively influences perceived hotel financial performance.

H1a: Commitment positively influences perceived hotel financial performance.

H1b: Trust positively influences perceived hotel financial performance.

H1c: Satisfaction positively influences perceived hotel financial performance.

However, it is not enough to focus on financial performance alone. AsAvelini Holjevac and Vrtodušić (1999) point out hotel performance can be observed through hotel effectiveness and efficiency. Hence, not just financial measures but also measures related to customer satisfaction are used in assessing hotel performance. As long-term relationships foster collaboration and focus on partners, this implies that a relationship quality might also have some influence on non-financial performance, like willingness to recommend (Huntley 2006), customer loyalty (Reichheld 2001), customer retention (Sin et al. 2002) or collaboration and joint value creation (Gummesson 2002). Therefore, considering that relationship marketing practices influence non-financial performance measures, it is reasonable to assume that high relationship quality, inherent to all good relationships in the market, will also improve hotel non-financial performance.

Therefore, we posit:

H2: Relationship quality positively influences perceived hotel non-financial performance.

H2a: Commitment positively influences perceived hotel non-financial performance.

H2b: Trust positively influences perceived hotel non-financial performance.

H2c: Satisfaction positively influences perceived hotel non-financial performance.

Relationships between the researched variables are presented in the conceptual model (Figure 1).

3. RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

3.1. Sample and data collection

Research was conducted on a sample of hotels in Croatia in period from June till October 2014. A convenience sample and the snowball sampling technique were used and a total 266 questionnaires were collected. The collection process used a Limesurvey platform. The initial sample included mail addresses from personal contacts and each participant was asked to forward the email, with a link to the survey, to his/her friends and acquaintances, working as managers in the field of marketing or similar in different hotels. Research focused on individual hotels rather than on hotel chains as each hotel is an independent functional unit and can have its own perspective of relationship quality among partners and hotel performance. Respondents were managers or employees in the marketing department. If a hotel did not have a marketing department, then employees from other departments, who perform marketing functions like sales or procurement, were asked to respond to the questionnaire.

The final research sample included 266 properly filled questionnaires used for further analysis. Analysis was done with SPSS 21 for Windows and LISREL 8.80.

3.2. Measures

Questionnaire was consisted of two parts. First part consisted of scales related to relationship quality and perceived performance, second part had several questions that were used to describe sample. Scales used in research are based on previous literature. Relationship quality was approached as a three-dimensional construct, consisting of trust, commitment and satisfaction. Hence, the scale fromMoorman, Zaltman and Deshpande (1992) was used to measure trust and commitment, while the scale fromKang, Oh and Sivadas (2013) was applied for measuring satisfaction. All scales for measuring relationship quality were 7-point Likert-type scales, anchored at 1 "strongly disagree" and 7 "strongly agree". Respondents were indicated, as research focused on hotel partners, that they should focus on relationships between all hotel partners like suppliers, hotel guests, tourist agencies, tourist offices and employees. Further, the scale fromRouziès and Hulland’s (2014) research for measuring financial and non-financial performance was applied. Respondents were asked to judge the improvement in hotel performance over the last two years. Their perception on the following financial indicators was sought: market share growth, sales growth and increased profits. In addition, respondents were questioned on their perception of non-financial indicators like increased customer satisfaction, increased customer value, a greater focus on customers, market success compared to competitors and developing stronger relationships with customers. In the judging process, they ranked perception of hotel improvements on performance indicators using a scale of 1 to 7, with 1 indicating "to a small extent" and 7, "to a large extent". All original scales were slightly modified to reflect a hospitality setting.

4. RESEARCH RESULTS

4.1. Sample characteristics

The research sample consists of 266 respondents. Their characteristics are presented inTable 1.

Source: Research results

The above table (Table 1) shows that the average respondent works in a hotel that operates on a seasonal basis (59.1%), has from 0-99 (34.4%) or 200 or more (34.1%) accommodation units, has 0-199 beds (37.5%) and has 10-49 employees (61.8%). Guests stayed in the hotels for an average of 4-7 days and the hotels had up to 34,999 overnight stays per year. Hotels are located on the coast (40.2%) and have four stars (41.3%).

4.2. Research analysis and hypotheses testing

After analysing the sample, research analysis was continued by testing the appropriateness of the used scales for further analysis. First, exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted using Principal axis factoring with oblimin rotation and Kaiser Normalisation. This method was used as theoretical background for all research constructs is present (Field 2009). As constructs are closely related and represent different dimensions of the same relationship quality construct, oblimin rotation was used as recommended byHair et al. (2010). As suggested byField (2009) on communality level of included indicators, after analysing the scale, one item (“Generally we don’t trust our partners”) was discarded from use in further analysis as it had communality lower than 0.5. Item was firstly recoded and as still communality level was low it was discarded from further analysis. The results of Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy and Bartlett’s test of sphericity indicate: KMO=0.901 and χ2=2225.018 (df=45, p<0.05).Hair et al. (2010) suggest that the threshold value for KMO should be 0.7 and that Bartlett’s test should be statistically significant. Therefore, based on these criteria, the sample is adequate and analysis can be continued. Upon EFA, a three-factor solution was retained, explaining 82.699% of variance in results. Factors in EFA that were used for further analysis are Satisfaction, Trust and Commitment. Results of EFA are presented inTable 2.

Source: Research results

In the previous table (Table 2) we can observe that Cronbach’s alphas range between 0.883 and 0.936. Therefore, all scales used for research have Cronbach’s alpha values above the recommended value of 0.7 (Nunnally 1967), indicating they are reliable for further analysis. In addition, the scales that were used for measuring performance were analysed to see if they were reliable for further analysis.

In EFA for perceived performance scales, we used common factor analysis in SPSS with oblimin rotation and Kaiser Normalisation.Hair et al. (2010) suggest the use of this method when we want to explore data and maximise loadings into assumed underlying factors. The Kaiser-Guttmann criterion suggests keeping one factor that explains 77.57% of variance in the results. However, upon carefully examining the theoretical background and items included in the research, it was decided to keep two factors, the first explaining 77.57% of variance, and the second, explaining an additional 6.82%. We based this decision on the fact that both financial and non-financial factors are equally important in building and analysing company performance and that it is reasonable to distinguish among them. Therefore, the two retained factors explain 84.389% of variance in research results. Further on, even if some items had loadings on two factors it was decided to keep them in subsequent analysis as their loadings on the factor, where they theoretically belong, are higher. The factors identified after EFA are “non-financial performance” and “financial performance”. Research results are presented inTable 3.

Source: Research results

Table 3 shows that both perceived non-financial and financial performance measures have high Cronbach’s alpha values, well above the threshold of 0.7 and, therefore, represent reliable scales for further analysis. Additionally, confirmatory factor analysis was performed to test the reliability and validity of constructs used in research. Constructs used in research are reliable if their composite reliability (CR) is greater than 0.6 (Bagozzi and Yi 1988) and if average variance extracted (AVE) is greater than 0.5 (Fornell and Larcker 1981). Results are presented inTable 4.

Source: Research results

Table 4 leads to the conclusion that all constructs used are reliable because values for composite reliability and average variance extracted are above the thresholds of 0.6 and 0.5, respectively. The validity, both convergent and discriminant, of the constructs used was tested. Convergent validity is present if the relationship between an indicator and underlying construct is significant (twice greater than standard error) (Anderson and Gerbing 1988, 416) or if the t-values of each indicator are statistically significant (Čater, Žabkar and Čater 2011).Table 1 (Appendix) indicates that convergent validity is present among the researched constructs. An additional criterion for construct validity is that AVEs should be greater than 0.5 (MacKenzie, Podsakoff and Podsakoff 2011). As this is also present (seeTable 4) it can be concluded that convergent validity exists. Next, discriminant validity was analysed. According toFornell and Larcker’s (1981) criterion, discriminant validity is present if the AVE score is higher than the squared correlations between that construct and other constructs in the model. Results of discriminant validity are presented inTable 5.

Note: Correlations are below diagonal; squared correlations above diagonal; average variance extracted on diagonal (bolded).

Source: Research results

By observingTable 5, it can be noted that discriminant validity is present in the researched sample. Therefore, based on previous analysis, the constructs used possess reliability, assessed by Cronbach’s alpha, average variance extracted and construct reliability, and validity assessed by convergent and discriminant validity. Further analysis uses factors that are composed as the average index of items that constitute the factor.

Multiple regression analysis was applied to test the posited hypotheses. In the models tested, “perceived financial performance” (Table 6) and “perceived non-financial performance” (Table 7) were identified as dependent variables, while “commitment”, “trust” and “satisfaction”, the dimensions of relationship quality, were used as independent variables. The enter method was used to select independent variables for entry into the regression model. Results are presented inTable 6.

Note: Dependent variable: Perceived financial performance; **p<0.01, *p<0.05

Source: Research results

Note: Dependent variable: Perceived non-financial performance; **p<0.01, *p<0.05

Source: Research results

In both models (Table 6 andTable 7), R2 values are statistically significant and the independent variables explain 42.4% and 47% of variance in the results. We can conclude that for both perceived financial and non-financial performance, commitment and satisfaction are statistically significant predictors. Commitment has a higher impact on performance (β=0.353 for perceived financial performance and β=0.437 for perceived non-financial performance) than satisfaction (β=0.337 for perceived financial performance and β=0.320 for perceived non-financial performance). Moreover, the impact of commitment on perceived non-financial performance (β=0.437) is slightly higher than on perceived financial performance (β=0.353).

The assumption of normality of residuals has been met. Tolerance and VIF are at an acceptable level, with the highest VIF value being 2.297 and the lowest tolerance value being 0.435. Average VIF is 2.086; hence, collinearity is not a problem because VIF is not substantially larger than 1 (Field, 2009). Residuals are uncorrelated since the Durbin-Watson test showed a value of 2.092. It is reasonable to expect 5% of residuals, that is, 13 residuals for our model, to be outside -/+ 2 standardized residuals. Our data indicate that 12 cases are more than +/-2 standardized residuals away, while five cases are more than -/+2.5 residuals away, suggesting that both models’ level of error is less than 1% per cent, implying that the model is acceptable. Also, in none of the cases is Cook’s distance larger than 1. An analysis of the Mahalanobis distance indicated that there is one case over 25, a cut-off point for large samples (Barnett and Lewis, 1978 inField, 2009). No cases have any influence over the regression parameters as all standardized DFBetas have values below 1.

Based on these results we can conclude that: (1) Hypotheses H1a and H1b are accepted. Hence, commitment positively influences perceived hotel financial (H1a) and perceived non-financial (H2a) performance; (2) Hypotheses H1c and H2c are accepted. Therefore, satisfaction positively influences perceived hotel financial (H1c) and perceived non-financial (H2c) performance; (3) Hypotheses H1b and H2b could not be accepted because the relationship between trust, as a relationship quality element, and perceived performance is not statistically significant.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

This study contributes to the theory of relationship marketing, especially in the hospitality context. This contribution is seen in approaching relationship quality as a three-dimensional construct in the hospitality industry and relating different dimensions of relationship quality to perceived hotel performance observed from a financial and non-financial perspective. Relationships, long-term ones in particular, are essential in relationship marketing (Reinartz and Kumar 2002). Companies build relationships with partners on a long-term perspective and create a network of partners. A relationship marketing approach provides a framework on which companies can approach their partners and build relationships based on value exchange. This also includes collaboration between partners and joint value creation (Gummesson 2002). Furthermore, if collaboration and the value-providing aspect within relationships is high, the relationship is considered as having a high level of relationship quality.

Exploring relationship quality within the hospitality industry can be approached from three cornerstones: commitment, trust and satisfaction among partners. This is in accordance with previous research (Ulaga and Eggert 2006;Palmatier et al. 2007;Ndubisi 2014) which indicates that relationship quality is consistent of these three elements. Taking care about partners and making them part of a team contributes to developing commitment among partners. This, together with building trust in partners’ decisions and actions, is important, because having reliable partners that will do their job right and that will be a match to a company’s business is important. In addition, having partners that are supportive, reliable and easy to work with is essential for developing good-quality relationships and building satisfaction with partners within a network.

The contributions of this research are seen in the following. First, relationship quality contributes to the development of perceived hotel performance. Results indicate that investments to improve relationship quality among partners will influence perceived hotel performance. A hotel, however, must differentiate between financial and non-financial performance. This is similar to the research ofLeonidou et al. (2014) indicating that relationship quality influences relational performance in an export-import context.Bowen and Shoemaker’s (1998) study show also in the hospitality industry that researched hotel guests and their loyalty as a non-financial performance indicator, as well as toKim and Cha’s (2002) research results showing that relationship quality has an influence over non-financial performance indicators in the hospitality industry.

Second, approaching relationship quality as a multidimensional construct helps differentiate between the influences that different relationship quality elements have on perceived performance. Commitment is found to be the most influential relationship quality element and it has more influence on perceived non-financial than financial performance indicators. This is followed by satisfaction with partners as an influencing relationship quality element, where satisfaction has greater influence on perceived financial performance indicators than on non-financial ones. These results are similar to previous research on commitment when considering non-financial performance like longevity in a relationship or propensity to stay in a relationship. Commitment reduces propensity to leave a relationship (Morgan and Hunt 1994) or provides an opportunity for a partner to develop a relationship (Ulaga and Eggert 2006). While the results of past research on satisfaction indicate that it can enhance loyalty (Reichheld 2001) or retention (Gustafsson, Johnson and Roos 2005), scarce direct evidence is found of the effect of satisfaction on financial performance.

Third, trust is found not to have a statistically significant influence over perceived hotel performance. This is similar to previous results (Ramayah, Lee and In 2011) which point out that trust has no influence either on collaboration or, consequently, on performance in tourism. Hence, this indicates that trust, as an element of relationship quality, has to be more fully researched in the tourism sector. Moreover this relationship deserves attention as trust and attitudes towards companies evaluated by business partners are dominantly under influence of price to quality ratio of company’s products and services (Vlastelica et al. 2018).

The research also has managerial implications when considering the influence of relationship quality on performance. When marketing managers in hotels want to enhance non-financial performance such as perceived customer value, greater focus on customers or building stronger relationships with partners, they should invest in strengthening commitment among partners. This is possible through more intense collaboration with partners, by including them in the creation of new services or opportunities to collaborate. On the other hand, when marketing managers want to enhance financial performance, such as market or sales growth, they should consider building satisfaction among their partners. This is possible by evaluating partners and selecting the ones that are more compliant with a hotel’s strategy or by selecting ones that are more prone to continue a relationship with the hotel.

Like any other, this study has its limitations. One limitation is seen in the convenience sample that was gathered using the snowball technique. Hence, research results are indicative of its nature but still point out some trends in the explored relationships between relationship quality elements and performance. Further, the sample structure does not match the hotel structure in Croatia with regard to the criteria of hotel stars, location or number of accommodation units. This issue could be resolved by adding additional hotels to the sample to match the average Croatian hotel structure. Focusing on perceived performance in hotels could also be considered as limitation. In questionnaire respondents were asked also on financial data but information they provided was confusing. Hence, further research could consider matching relationship quality data with financial results published in available financial publications. Perceived performance both from financial and non-financial perspective should be tested with some other scale, as one used was not performing well in EFA. Still these results can be used as indicative and are considered to point out trend of influence of relationship quality on performance in hospitality industry. Considering ideas for further research, it would be interesting to compare hotels with other hospitality companies such as hostels, campsites, family-run hotels and private accommodation. In addition, it would be interesting to relate these results to hotel partners and tourists to provide different perspectives and triangulation of results. Additional insight would be also gained by analysing the existing sample based on hotel location or number of overnight stays. In conclusion, when approached from a multidimensional perspective, relationship quality, especially in the hotel industry, offers a number of possibilities for new research ideas.