INTRODUCTION

Tourism is a widespread industry with economic, social and cultural aspects “created by, for and through tourists” (Munar 2007, 69). Also called as “chimneyless industry”, tourism is a significant means of financial development and socio-cultural integration especially for emerging countries. Turkey, as one of the emerging economies, is an important tourist destination regardless of the time of the year thanks to its natural, historical and cultural attractions. It is a market with an annual income of 26.283.655.948 USD received from 38.620.345 tourists according to 2017 statistics (TurkStat 2018). Although the rapid growth of international tourist flows in Turkey, one of the most important challenges for the tourism industry is the lack of well-educated labor force (Kusluvan and Kusluvan 2000). However, the productivity and sustainability of this industry depend largely on the quality of the local personnel working in this sector. In this respect, vocational education and training of tourism students become an important issue. Particularly teaching foreign language(s) is an inevitable and critical part of this education, since communication is the key while serving the tourists speaking different languages. Thus, tourism students should be taught one or more foreign languages at adequate levels. Moreover, in many higher educational institutions, tourism education programs are taught in English in the competitive global market (Maggi and Padurean 2009, 51). One of the most spoken languages worldwide is English. So tourism students try to learn English at first as well. English helps to communicate the students with foreign people easily (Yashima 2009, 2). Communication with tourists is not only about speaking them using a foreign language, it is also about knowing their cultures and building favorable relationships (Huang 2013). Today, as English becomes an international language, learning English makes it easier to communicate with most foreigners and to learn any nation’s culture (Kormos et al. 2011). However, students should also learn other languages to communicate with people who come from other countries as a tourist at most. For example, in Turkey, the most incoming tourists are from Russia and Germany. So, the tourism staff who can speak Russian and German in addition to English gains an advantage over their colleagues. Because tourists have been coming from different countries and cultures as well, they need people who speak the same language with them (Akgöz and Gürsoy 2014). The languages provide a bridge between the staff and tourists in the hospitality sector (Kostic and Grzinic 2011).

As briefly summarized above, the growing importance of the tourism has aroused the interest of the researchers to study about the education in tourism (Juaneda et al. 2017). In this vein, the current paper aimed to define International Posture levels of Turkish tourism and hospitality students, who are potential sources of work-force for the tourism industry. To achieve that, this study examined the relevant literature and conducted some analyses to discover the interaction between international posture and some independent variables including gender, school type, employment background in jobs requiring contact with foreigners, perceived proficiency in languages including English, German, and Russian.

1. LITERATURE REVIEW

Becket and Brookes (2012) point out that one of the requirements of a global ready graduate is knowledge and understanding of (1) core subject/discipline in different cultural contexts, (2) global contemporary issues, (3) different cultures and places, (4) cultural norms and expectations and (5) languages. The major goal of contemporary language curricula around the world is to provide communicative competence between individuals who come from different cultural backgrounds and speak different languages (Larsen-Freeman 2000;Richards and Rodgers 2001;Yashima et al. 2004). It is important that students should have diverse cultural backgrounds and different levels of employment background (Kim and Davies 2014). According toGardner and Lambert (1972), one of the motivations for learning a foreign language is to learn about the second language’s culture. Tourism destinations have different types of cultures as tourist culture and local culture (Reisinger 2009). So, these cultures bring their novel cultural behaviour together. The intercultural contact through tourism will lead to enhanced language learning motivation (Dörnyei and Csizér 2005). Also, it is expected that learning a foreign language may enhance cultural integrativeness.

Besides,Errington (2009) brings the issue of culture as a negative component, i.e. he discusses that “if the Chinese students change their attitudes, values and opinions, this could be seen by some as a process of losing ‘Chineseness’ and gaining ‘Westernness’” (p. 6). The concepts of language and citizenship have always been related to each other very closely in a simple way (Guilherme 2007). A local culture -especially a small community- is influenced adversely by the development of tourism (Macleod 2004).

Either positive or negative, such intercultural attitudes are also expressed in some attitudinal-motivational theories in foreign language teaching. For example, Gardner defines an attitudinal construct called integrativeness, which “reflects the individual's willingness and interest in social interaction with members of other groups” (Gardner and MacIntyre 1993, 159). It involves “individual’s orientation to language learning that focuses on communication with members of the other language group, a general interest in foreign groups, especially through their language, and favourable attitudes toward the target language group” (Gardner 2005, 10). Similarly,Yashima and Zenuke-Nishide (2008) postulate a specific international attitudinal construct called International Posture, which reflects “a tendency to see oneself as connected to the international community, to have concerns for international affairs and a readiness to interact with people other than Japanese.” (p.568). It includes “interest in foreign or international affairs, willingness to go overseas to stay or work, readiness to interact with intercultural partners … openness or a non-ethnocentric attitude toward different cultures, among others.” (Yashima 2002, 57). Compared to Gardner’s concept of integrativeness, international posture “tries to capture a tendency to relate oneself to the international community rather than any specific L2 group, as a construct more pertinent to EFL contexts” (Yashima 2009, 145).

Such terms as integrativeness and international posture refer to attitudes towards the culture of a foreign language or intercultural orientation (Hayashi 2013). If one is engaged in intercultural communication, he/she should also consider socio-cultural expectations of individuals (Bowe and Martin 2007). Mass media have a crucial role in providing social consensus, with understanding different cultures and bringing close together the communities (Lee and Yang 1996;Novais 2007). Thus, interest in international news, international affairs, and international issues (e.g. global warming, the European Union and the Middle East) helps people to understand different cultures and to communicate to the world. Tourism is one of the pivotal international service sectors that brings many different cultures into contact with each other (Taylor and McArthur 2009;Lustig and Koester 2010).

Although much research has been concerned with EFL classrooms (Peng and Woodrow 2010), willingness to communicate (WTC) (MacIntyre 2007) and the second language (L2) motivation of the students (Kormos and Csizér 2008;Siridetkoon 2015), there is still limited research on tourism industry and international posture. Furthermore, the effect of speaking multiple languages is an under-researched field of study. Thus, the present study attempts to fill in this gap about the relationship between international posture and the research field of tourism.

This study is significant because foreign visitors usually make contact first and foremost with people working in the tourism sector. Their attitudes towards international quests are very decisive in maintaining a sustainable customer satisfaction. Thus tourism and hospitality programs should provide their students with favorable intercultural attitudes. However, there is limited research on to what extent tourism and hospitality students possess such an intercultural awareness or how these attitudinal variables are interrelated with other independent variables. Thus this study intended to investigate Turkish tourism and hospitality students’ levels of International Posture with regard to some variables. Accordingly, this study attempted to answer the following research questions:

What is the level of Turkish tourism students’ International Posture?

Do Turkish tourism students’ levels of International Posture differ significantly by their gender and school type?

Do Turkish tourism students’ levels of International Posture correlate significantly with their duration of work experience in jobs requiring contact with foreigners?

Do Turkish tourism students’ levels of International Posture correlate significantly with their perceived proficiency in English, German, and Russian languages?

2. METHOD

2.1. Design

This study was designed based on a baseline survey model followed by an associational one. The former phase of the study aimed to determine the tertiary Turkish tourism students’ levels of international posture based on the data obtained using the adaptation of Yashima’s (2002,2009) andYashima et al.’s (2004) International Posture Scale. The second phase was conducted to discover the interaction of international posture with some independent variables including gender, school type, employment background in jobs requiring contact with foreigners, perceived proficiency in languages including English, German, and Russian.

2.2. Research Group

Participants of the study were selected using convenience sampling method. Though cannot be considered representative of any population, convenience sampling is used especially when it is extremely difficult to select a random or systematic non-random sample (Fraenkel et al. 2012). Since it was extremely difficult to have access to and select from all tourism and hospitality schools around Turkey (127 two-year vocational schools and 23 four-year faculties in state universities), we selected the four of them which are most available to our reach during 2012-2013 academic year. As a result, 254 volunteering tourism students studying at four universities [Ankara Gazi University (n=87), Malatya İnönü University (n=40), Tokat Gaziosmanpasa University (n=97), Edirne Trakya University (n=30)] took part in the study. Out of these participants, 40 were studying at two-year vocational schools and 214 were studying at four-year faculties (n=214). In terms of gender, 81 (31.9%) were females and 173 (68.1%) were males. 133 (52.4%) students worked at a job which is suitable for having intercultural experience and 121 (47.6%) students did not. The main intercultural experience period was 3 months (21.5%), followed by 6 months (20.7%), 12 months (13.2%).

2.3. Instruments

The data was collected using a participant information form and the Turkish adaptation ofYashima’s (2009) “International Posture Scale”. The scale items were originally developed and validated in Japanese across several previous studies (Yashima2002,2009 andYashima et al., 2004). In the present study, the updated version of the International Posture with 20 items under 4 factors was used (Yashima 2009). To this end, first we contacted Yashima to ask for permission and she sent us the non-validated English translation of the original Japanese version of the scale. The adaptation process began with a translation back-translation procedure. Commonly used as a quality assessment tool in instrument adaptation studies, back-translation technique requires the translation of the source text into target language, second (back) translation of the already translated text again into the source language, and finally the comparison of first original source text and the output text of the back translation process to make sure there are no discrepancies (Colina et al. 2017). For this purpose, first, the writers translated the English version of 20 items into Turkish and next an independent bilingual translator was asked to retranslate the Turkish version back into English. Finally, this committee with three members reviewed the backward translation and the original version of the items and negotiated on the final Turkish version of the items with some cultural adaptations. These cultural adaptations included replacing word ‘Japan’ with ‘Turkey’ in item 1 and words ‘north-south issues’ with ‘European Union and the Middle East’ in item 19 (seeTable 1). Following the translation-back translation studies, the construct validity and reliability analysis of the Turkish version of the scale were tested with the data set obtained from the study. To test the construct validity of the “International Posture Scale”, a principal components factor analysis technique with varimax rotation was used. The reliability of the scale was estimated based on Cronbach Alpha internal consistency and Item-total correlation coefficients. The results of the analysis are presented inTable 1.

Note: Factor loadings under 0.30 are not displayed

* Negatively-worded reverse items.

Before the factor analysis was conducted, statistics on Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) and Bartlett's Test of Sphericity were tested to measure the sampling adequacy, which yielded favorable results [KMO= .861; X2=1270,255, p<.05 ]. As seen intable 1, the factor analysis procedure yielded, a three-factor construct with 16 Likert items, after four items in the original scale were discarded due to low or overlapping factor loadings, and two factors (Interest in International News and Having Things to Communicate to the World) were combined under one factor. The adapted version of the scale explained 51.59% of the total variance, with factor loadings ranging between 0.505 and 0.793. Factors yielded moderate-to-high Cronbach Alpha coefficients (Intergroup Approach-Avoidance Tendency=.792; Interest in International Vocation or Activities=0.662, and Interest in International News & Having things to communicate to the world=0.809; and total scale=0.858). Estimated item-total correlation coefficients for all 16 items ranged between 0.719 and 0.354.

The first factor of the scale with seven items, “Interest in international news& having things to communicate to the world”, measures the students' interest in foreign affairs and international news and having opinions on international matters. The second factor of the scale with five items, “Intergroup approach-avoidance tendency”, reflects the students' tendency to approach or avoid foreigners. And the last factor with four items, “Interest in international vocation or activities”, measures the students’ interest about their international career and living in other countries (Yashima2002,2009). Items were designed in 5-point (5-Strongly Agree and 1-Strongly Disagree). To interpret the scores on the same 5-point metric, factor/scale total score is divided by the number of items in that factor/whole scale (e.g. total score / 5 for Intergroup approach-avoidance tendency factor, and total score / 16 for total International Posture scale). Higher scores indicate higher International Posture, i.e. favorable attitudes toward the international community, while lower scores refer to lower International Posture, i.e. less favorable attitudes toward the international community.

2.4. Data Analysis

The data were analyzed using descriptive statistics, and comparison and correlation analysis in line with the research questions. Accordingly, to answer the first research question data were analyzed using descriptive statistics (mean scores, standard deviations, min. and max. scores), with the results shown in the table and figure. For the second research questions was participants’ scores were compared by gender and school type using independent samples t-test, since the normality assumptions were accepted based on the skewness coefficients which ranged between -0.225 and -0.750. Finally, the third and fourth research questions regarding the associations among variables were tested using Pearson correlation analysis. The significance level was set to p<0.05.

3. RESULTS

The results of the analysis were presented below with the order of research questions.

3.1. Turkish Tourism and Hospitality Students’ Level of International Posture

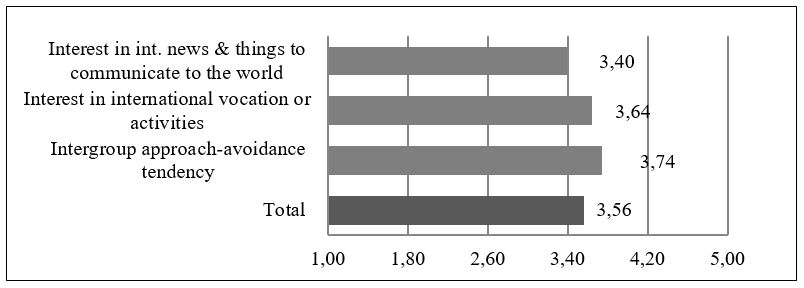

Table 2 andFigure 1 below show the level of Turkish tourism students’ international posture level.

3.2. Turkish tourism and hospitality students’ levels of International Posture by gender

Table 3 below shows the results of comparative analysis on Turkish tourism and hospitality students’ levels of International Posture by gender.

As seen inTable 3, the results of independent samples t-test analysis revealed that there is no statistically significant difference between the international posture scores of male and female students in terms of Intergroup Approach-Avoidance tendency (t(252)=-0.859, p>0.05) and Interest in International Vocation or Activities (t(252)=-1.460, p>0.05) factors. However, male students were found to have significantly higher international posture than female students in terms of their scores from Interest in International News & Having Things to Communicate to the World factor (t(252)=-2.545, p<0.05) and total scale (t(252)=-2.132, p<0.05). However, the calculated effect sizes for these differences were small (d=0.34 and d=0.29, respectively).

3.3. Turkish tourism and hospitality students’ levels of International Posture by school type

Table 4 below shows the results of comparative analysis on Turkish tourism and hospitality students’ levels of International Posture by school type.

As seen inTable 4, the results of the independent t-test for the school type variable revealed that there was a statistically significant difference between the international posture scores of vocational school students and undergraduate students only in terms of Intergroup Approach-Avoidance tendency factor (t(252)= 2.705, p<0.05). Accordingly, vocational school students (mean= 4.1; s=0.72) had statistically significantly higher tendency to approach foreigners than undergraduate students (mean= 3.67; s=0.95). Considering the moderate effect size (d=0.47), this difference can also be regarded as practically significant, as well.

3.4. Correlation between Turkish tourism and hospitality students’ levels of International Posture and their duration of work experience

Participating students were also asked about how long they have worked in a job which required contact with foreigners. The descriptive analysis revealed that so far Turkish tourism and hospitality students have worked in a job involving contact with foreigners for 3,25 months (s=4,47) on average (min.=0 and max.= 22). The results of correlation analysis between Turkish tourism and hospitality students’ levels of International Posture and their duration of such work experience are shown inTable 5 below.

*Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).

**Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

The Pearson correlation analysis results suggested that there were statistically significant positive but rather small correlations between participants’ duration of work experience in jobs requiring contact with foreigners and their international posture scores in total (r= .157, p< .05), in terms of Interest in International Vocation or Activities scores (r= .197, p< .05), and in terms of Interest in International News & Having Things to Communicate to the World scores (r= .151, p< .05). That means as their work experience in jobs requiring contact with foreigners increase their interest in International Vocation or Activities and International News as well as the things they have to communicate to the world also increase to some extent.

3.5. Correlation between Turkish tourism and hospitality students’ levels of International Posture and their perceived foreign language proficiency

Participating students were also asked to rate their proficiency in English, German and Russian from 0 (very poor) to 5 (highly competent). The descriptive analysis revealed that Turkish tourism and hospitality students perceived their competency in English slightly above moderate level (mean=3.24; s=0.99), while they perceive their competency very poor in German (mean=1.27; s=1.37) and Russian (mean=0.90; s=1.26). Results of correlation analysis between Turkish tourism students’ levels of International Posture and their perceived proficiency in English, German, and Russian languages are shown inTable 6 below.

**Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

As seen inTable 6, results the Pearson correlation analysis suggested that tourism students’ Intergroup Approach-Avoidance Tendency is significantly and negatively correlated with their perceived proficiency in English (r= -.163, p< .05) and German (r= -.291, p< .05), though with small magnitudes. Also, there found a statistically significant small negative correlation between total international posture scores and perceived proficiency. It is remarkable that this negative correlation is almost moderate between Intergroup Approach-Avoidance Tendency and perceived proficiency in German. This suggests that as the students’ perceived proficiency especially in German increases their tendency to approach to foreigners decreases, i.e. their tendency of avoidance increases.

4. DISCUSSION

This study investigated Turkish tourism students’ levels of International Posture, which is defined, in the present context, as the tendency of Turkish tourism students to see themselves “as connected to the international community, to have concerns for international affairs and a readiness to interact with people other than [Turkish]” (Yashima and Zenuke-Nishide 2008, 568). The results revealed that participating students have more than moderate level of International Posture. Thus, the participating tourism students can be said to see themselves moderately connected to the international community and are moderately interested in international affairs and are moderately ready to interact with people other than Turkish. Similarly,Ulu et al. (2015) have found that Chinese students held medium-to-high levels of international posture. According toPlatsidou et al. (2017), international posture is a part of international orientation “as a positive predisposition to other cultures” which also constitute “strong L2 learning motivating forces” (p. 2). As a matter of fact, international posture should be regarded as critical for tourism students, since a high level of international posture is associated with speaking with international students, helping foreigners, reading the foreign language newspapers and, watching foreign language TV programs (Yashima 2009).

Further analysis showed that especially male students have significantly better International Posture than female students in terms of their scores from “Interest in international news & having things to communicate to the world” factor and the total scale. In a previous study,Hjalager (2003) also found that men tend to see an international career in tourism a plus, implying more favorable attitudes. However, in another study,Yashima (2010) found female students who participated in international volunteer projects show greater interest in such activities than their male peers.

Moreover, two-year vocational school students had significantly better International Posture than four-year undergraduate students in terms of scores from “Intergroup approach-avoidance tendency” factor and total scale.Kormos and Csizér (2014) have found a strong link between international posture and instrumental motivation (e.g. utilitarian benefits related with being able to speak the second language, such as higher salary, better jobs) for all groups of secondary school students, university students, and adult language learners.

This study also found statistically significant positive correlations between participants’ duration of work experience in jobs requiring contact with foreigners and their international posture scores in total, in terms of “Interest in international vocation or activities” scores, and in terms of “Interest in international news & having things to communicate to the world” scores. Communication with international tourists contains difficulties for many tourism students because of the internal differences between the languages and cultures (Nguyen 2011). Thus, the students who want to work in the tourism industry should know about the visitors’ cultures and traditions in order to understand their lifestyles better (Leslie et al. 2002). Working at international jobs involving contact with foreigners, preferably in the country of the target culture, is a good opportunity to know about their culture. However,Hjalager (2003) notes that although international careers seem to be attractive, tourism students tend to work in an international job at their countries or in countries which are culturally close, because they consider about their quality of life more important.

Finally, tourism students’ “Intergroup approach-avoidance tendency” scores and total scores were found significantly and negatively correlated with their perceived proficiency in English and German. This interesting finding, which suggests a reverse interaction between perceived language proficiency and positive attitudes towards foreigners, seems to disagree with previous research findings. For example,Gardner (2009) suggested that English speaking students who expressed integrative reasons for learning French (matching rather an intergroup approach tendency of the international posture), were motivated more and had more favorable attitudes toward French Canadians and were more successful at learning French. This finding can have several explanations: First, students may be avoiding the cultural integrativeness asErrington (2009) pointed out. Second, they might think that they just know the target language and there is no need to learn more about that culture. As a matter of fact, in a previous study, tourism students emphasize that the aim of learning a foreign language is just to work readily in the tourism industry and communicate with people from other cultures (Balci 2016). Likewise,Leslie et al. (2002) point that among the tourism students, the least important reason is to develop understanding of the culture of a country (84%) and by the way, the most important reason to study a foreign language is to increase job opportunities (49%) and followed closely by improving foreign language skills (45%). However, tourism workers should pay attention to the cultural diversity of their customers (Truong and King 2009) either to excel in their profession or simply to find better job opportunities. Thus, it is suggested that while teaching foreign languages especially for English and German to tourism students, cultural aspects should also be developed in order to emphasize the intercultural features of these languages as well.

Considering the quality of services provided in the tourism industry, having favorable foreign language skills is associated with better cross-cultural service skill (Leslie and Russell 2006;Kostic and Grzinic 2011). However, in Turkey, one of the specific problems encountered in tourism education is learning a foreign language. Because foreign language competency levels of tourism students are insufficient, it is hard to communicate with foreign tourists and to find a top-level job in tourism companies (Türkeri 2014). The finding regarding the negative correlation between perceived proficiency in English and German and positive attitudes towards foreigners make the situation even worse. Although a lack of language proficiency can be more favorable in leading people to intercultural communication (Mancini-Cross et al. 2009), it is not desirable to have the situation vice versa, i.e. high language proficiency hindering people from intercultural communication. That causes a kind of dilemma in tourism context: provision of high-quality services in tourism industry needs better language skills, however, better language skills are associated with less favorable attitudes towards foreigners. To handle this problem better, the sociocultural component should be integrated into the syllabus so as to develop the learners’ cross-cultural awareness (Platsidou et al. 2017).

CONCLUSION

The productivity and sustainability of the tourism industry depend largely on the quality of the staff. It is expected that tourism students whom the foreign visitors encounter first and foremost should gain favorable language skills and attitudes towards foreigners, their cultures, or international communication and activities. Especially, teaching foreign language(s) is a critical part of the education, because communication is the key while serving the tourists speaking different languages. This study intended to examine and discuss about the Turkish tourism students’ levels of International Posture. As a result, it was found they see themselves moderately connected to the international community and are moderately interested in international affairs and are moderately ready to interact with people other than Turkish. However, to achieve a higher level of service quality and customer satisfaction, tourism students should be expected to develop higher international posture, especially through a better language education policy. As a matter of fact, this study also found that as the students’ perceived proficiency especially in German increases their tendency of avoidance from foreigners increases. Thus, the curricula implemented in tourism schools should aim at improving not only language skills but also more favorable attitudinal intercultural learning outcomes in students. Teachers should develop the lesson plans about international issues such as the European Union and the Middle East model and encourage the students to learn ore about the target cultures.

This study has several limitations that provide opportunities for additional international posture research in tourism. The current study is limited to the tertiary Turkish tourism students and three languages, particularly to English, German and Russian. Testing the International Posture scale in different education stages and community environments as well as in different languages would have a significant contribution to future research.