INTRODUCTION

Today’s tourists have become more interested in authentic and memorable food tourism experiences at tourist destinations that provide local culture, traditions, way of life and social interactions with local people (Li et al. 2021;Stone et al. 2018). Food tourism, a form of creative tourism (Hjalager and Richards 2002), is a growing tourism phenomenon attracting billions of tourists to visit destinations (UNWTO 2021). Food can be appealing for destination marketing and development in several ways. First, food is a symbol of identity and heritage that provides sense of place (Boyd 2015) and memorable experience (Hsu and Scott 2020). Second, food is a significant dimension differentiating a destination from others (Okumus et al. 2007). Third, food can be a primary tourism motivation to visit destinations (Rousta and Jamshidi 2020) attracting tourists all year round (Andersson et al. 2017). Fourth, food provides opportunities to promote local culture, diversifies tourism demand and enhances the value chain (UNWTO 2019). Lastly, local cuisine contributes to the Sustainable Development Goals by promoting local economy of the destinations (UNWTO 2021). Despite its multiple contributions to the destination, food tourism research still receives very little attention from tourism researchers (Okumus 2021).

One of the indicatorsidentifying a high potential food tourism destination is the growing number of food tours catering for food tourists who are willing to spend time and money for culinary knowledge and authentic food experiences (Getz et al. 2014). Examples of the leading countries offering food tours are France, Portugal, Spain, Germany, Korea, Hong Kong, Thailand, Denmark, Italy, China, and Japan (The Guardian 2019). Food tours are generally arranged in a small private group for several hours to local dining food places (Kaushal and Yadav 2021). They are often led by chefs, journalists or cookbook authors on either walking tours or local transportations (Abel 2017). Food tourists would gain insights into local cuisine that they are unable to come across otherwise. To date, the understandings of tourists’ experiences and satisfaction with food tours are still limited. Food tour destinations are therefore facing challenges to understand the needs and expectations of food tourists (Stanley and Stanley 2015).

There has beena growing number of tourists visiting Asia specifically for food (Henderson 2009). Thailand is ranked as one of the world’s top ten food destinations (Li 2021). Food is a significant tourist motivation to visit Thailand to experience various food activities (Kiatkawsin and Han 2017). Bangkok is rated as one of the world’s best street food tour destinations (The Guardian 2019) because the tours reflect Thai way of life, vibrant culinary scene, unique atmosphere and meaningful experiences (Tourism Authority of Thailand 2020;Jeaheng and Han 2020). Street food tours allow tourists to taste, learn and gain cultural knowledge of the destinations through their local cuisine and dining customs (Ko 2015). Since food tourism research has concentrated only on western countries, theoretical development and practical implications thus require further research beyond their boundaries (Henderson 2009). At present, research gaps still remain in the area of food tour activities as well as specific types of cuisine (Okumus 2021).

Literature on food tourism is still in its developing stage and thus needs further empirical evidence from tourist experiences and evaluations (Moscardo el al. 2015) in several aspects. Firstly, the experience economy model (Pine and Gilmore 1999) has been directly applied as a theoretical framework to explain food tourism experiences (Wijaya et al. 2013). Secondly, there is still an argument that food tourism experiences could possibly be beyond the framework of the said model (Laing and Frost 2015). To date, there are still limited studies to verify the aforementioned assumption and argument. Hence, these issues remain the research gaps in food tourism literature. This study therefore examined whether and how the experience economy model could explain the street food tour experiences. The study also investigated the role of street food tour experiences on satisfaction and behavioural intention. The findings provide theoretical advancement in food tourism and practical implications for food tour destinations.

1. LITERATURE REVIEW

1.1 Food tourism

Food tourism, a luxury niche tourism, refers to “a visitation to primary and secondary food producers, food festivals, restaurants and specific locations for which food tasting and/or experiencing the attributes of specialist food production region are the primary motivating factors for travel” (Hall and Sharples 2003, 10). Food tourism offers tourists with exciting and authentic food experiences including tastes, culture, heritage and customs (Ellis et al. 2018). Such sensory awareness and involvement with food activities offered at the destination can lead to special bonds with the place (Mitchell and Hall 2003).

A framework of food tourism research has been conceptualized into three perspectives (Ellis et al. 2018); activity-based, motivation-based and mixed perspectives. An activity-based perspective focuses on food-related activities such as visits to food production sites, cooking classes or food events (Che 2006). A motivation-based perspective refers to the desire to experience food at a specific destination (Bertella 2011) or a certain kind of food (Presenza and Iocca 2012). A mixed perspective looks at food consumption activity motivated by food interest (Adeyinka-Ojo and Khoo-Lattimore 2013). Past food tourism researchers have mostly paid attention to satisfaction (Lin and Chen 2014), perception and attitudes (Guan and Jones 2015) and preferences (Getz and Robinson 2014) regarding local food and services offered at the destinations. However, studies focusing on specific food activities and actual tourist consumption experiences are still under-researched (Okumus 2021;Frisvoll et al. 2016).

Food tour research is an emerging research area conducted in many leading food destinations such as Korea (Ko et al. 2018;Ahn and Yoon 2016), Slovenia (Istenič and Bajec 2021), Australia (Flowers and Swan 2017) and Turkey (Seyitoğlu 2020). For food tourists in particular, food tours are considered as food pilgrimages to discover authentic food experiences at the real places to learn about traditions and heritage of the destination (Laing and Frost 2015). Street food in Asia including Thailand is prevalent and also popular among food tourists since it offers a wide variety of local food with fresh ingredients (Cifci et al. 2021) and allows tourists to interact with local people (Henderson 2019). Recent studies (Jeaheng and Han 2020,Chavarria and Phakdee-auksorn 2017) suggest that street food successfully attracts foreign tourists to visit Thailand. Authencity is an important factor in the production and consumption of food experiences (Lunchaprasith and Macleod 2018).Kattiyapornpong et al. (2022) found that tourists learned Thai culture and history through their participation and interaction in food-related tourism activities (e.g. street food tours and cooking classes) and local guides took the significant roles in sharing history and food culture with tourists. This particular tourism trend has led to a growing number of street food tour businesses in Bangkok. In contrast, research into this particular tourism sector is still lacking (Cifci et al. 2021).

1.2 Experience economy model and beyond

Tourist experiences have received increasing attention in tourism research (Godovykh and Tasci 2020). Tourist experience is a significant factor leading to satisfaction and re-visitation (Lee et al. 2020). In the context of tourism and hospitality, experience economy model research however is still in its early stage (Chang 2018). The experience economy model (Pine and Gilmore 1999) has been directly applied into food tourism literature explaining that experiences occur within a person that is physically or emotionally engaged with an event and memorable impressions. The model focuses on two major areas; customer participation (active or passive) and connection with the surroundings (absorption or immersion). A framework of four realms of experience (Pine and Gilmore 1998) comprises the followings: educational (active, absorption), escapist (active, immersion), esthetic (passive, immersion) and entertainment (passive, absorption).

Past tourism studies (Lee et al. 2020;Song et al. 2015;Hosany and Witham 2010) adopted the experience economy model in the contexts of cruise tourism, rural tourism and natural tourism. In food tourism literature, food tourism experience is assumed to be grounded on the experience economy model (Ellis et al. 2018). Researchers applied the model to studies on the assumption that it can fully explain food tourism experiences.Getz et al. (2014) described the four realms of experience economy model in the food tourism perspective as follows: education (the desire to learn new cuisine and heritage), esthetic (all senses manifesting tastes, smells, sights and sounds, ambience and atmosphere), escapist (getting away from the routine and everyday world) and entertainment (entertainment premises and events which are fun and enjoyable). Recent research revealed that these four dimensions affected sharing food experiences (Soonsan and Somakai 2021).Lai et al. (2021) found that the entertainment dimension of food experience has the greatest effect on e-WOM intention.Suntikul et al. (2020) indicated that tourist experiences of cooking classes were influenced by a combination of both entertainment and escapist realms. This study argues that there is also a need to further examine the application of the experience economy model in other food tourism contexts to better understand the extent to which it can explain the food tourism experiences.

Some scholars further argue that food tourism experience is such a uniqueand authentic experience that it cannot be simply explained by the four realms of experience economy model.Kim and Eves (2012) suggested that food tourism experience further involved cultural experiences, sensory appeal, interpersonal relations, excitement and health.Laing and Frost (2015) strongly argued that there should be another fifth realm of experience, exploration, comprising of the three dimensions: emergent learning (eating like locals), interest in authencity (local food ingredients and specialties) and sustainable livelihood (keeping the local food heritage alive). A sense of authencity with new, engaging and sensory experiences in particular is regarded as a unique element of food experiences (Mhlanga 2020) for food tourists to fully experience authentic cuisine in the original cultural settings (Long 2006). At present, the argument on the exploration dimension has yet to be investigated especially in the area of street food tours.

1.3 Satisfaction and behavioural intention

Satisfaction and behavioural intention are considered as outcomes of tourist experiences reflecting their well-being after the trip (Godovykh and Tasci 2020). Satisfaction, a post-purchase evaluation, refers to how positive a tourist experience is and to what degree the purchasing experience incites feelings of positivity (Rust and Oliver 1994). Behavioural intention refers to an individual’s specific planned behaviour and likelihood of action based on expectations (Fishbein and Ajzen 1975).

It has been a challenging task for destination marketers to satisfy contemporary tourists who are constantly searching for unique tourism experiences (Lopez-Guzman and Sanchez-Canizares 2012). Local food related activities such as viewing, preparing, cooking and consuming are authentic, entertaining and sensory experiences for tourists (Mak et al. 2017). Furthermore, past research indicated that local food could be a powerful magnet for destination marketing. Positive food experiences could bring excitement to life (Rust and Oliver 2000), enhance tourist satisfaction (Seo et al. 2017;Neild et al. 2000) and influence future behavioural intentions (Lai et al. 2021;Choe and Kim 2018;Bianchi 2017;Ji et al. 2016).

The success and tourist satisfaction of food tours come from different factors. It relies on a strong cooperation of industry partners such as restaurants, guides and local people to enhance the tourist experience of food tours (Andersson et al. 2017). Furthermore, tour guides are also vital for providing fun and memorable experiences leading to satisfaction and repeat visit (Caber et al. 2018). To date, there are plenty studies on relationships between food and cultural experiences but research on the influences of specific food activities such as food tours on satisfaction and behavioural intention is insufficient (Ozcelik and Akova 2021;Stone et al. 2018). Such insights would provide competitive advantages for food tour business and destination marketing.

2. METHODOLOGY

2.1 Using Big Data

Big data is increasingly popular in both academic and marketing research (Li et al. 2018;Mariani et al. 2018). Collecting data from online reviews is one of the novel methods of using Big Data (Correia and Kozak 2022;Bigne et al. 2021). Past studies suggest that online reviews are useful to understand tourists’ perception (Wu and Pearce 2014), decision making criteria (Rabadán-Martín et al. 2020), overall tourism experiences (Lu and Stepchenkova 2015) and their satisfaction (Sangkaew and Zhu 2022). The study focuses on the reviews of Bangkok street food tours posted on TripAdvisor, a source of Big Data widely used in tourism research (Padma and Ahn 2020;Hu and Trivedi 2020). It allows researchers to handle the issue of representative samples since it virtually covers the entire population of the study (Gerard et al. 2016). Furthermore, the reviews are more insightful than score ratings since tourists can express their feelings, emotions and experiences (Liu and Park 2015).

2.2 Data collection

Online reviews of Bangkok food toursposted on TripAdvisor between January 2019 and March 2020, a period before the COVID-19 outbreak in Thailand, were collected in April 2021. Bangkok was selected since it was listed as the world’s best food tour destinations (The Guardian 2019). The study adopted past research approaches (Sangpikul 2021;Padma and Anh 2020;Stoleriu et al. 2019) using TripAdvisor for data collection. First, the study identified suitable and well-established food tour companies having at least 50 reviews during the period of data collection to ensure reliability of the data. As a result, there were four companies included in the study, with tour duration of 3 to 4 hours. An example of a Bangkok food tour company is shown in Figure 1. Second, only English-language reviews from international tourists were included in the study. Third, data were collected in four major areas: 1) food tour satisfaction rating scores ranging from 1 (terrible) to 5 (excellent) 2) textual descriptions posted by the reviewers 3) revealed personal information such as country, traveler type and 4) number of review contributions. The extent of personal information was voluntarily provided by the reviewers’ decisions. Figure 2 shows an example of a food tour review.

2.3 Data analysis

The study applied quantitative content-analysis using text mining software, KH Coder, recently introduced into tourism studies (e.g. Chen and Tussyadiah 2021;Padma and Ahn 2020;Hu and Trivedi 2020) to identify patterns of travel experiences from TripAdvisor. Data were read and reviewed by two independent researchers to ensure that the information was related and consistent to the emerging themes. There were three steps in quantitative content-analysis analysis: 1) word frequency analysis 2) co-occurrence network analysis 3) key words in context. The data set for an analysis had 57,025 tokens (the total number of words in the entire target data) and 3,035 word types (number of unique word types). Data were initially pre-processed by taking away articles and auxiliary verbs. The remaining 21,923 tokens and 2,666 word types were used for further analysis. Mean of term frequency was 8.22 and the standard deviation was 37.17.

3. FINDINGS

3.1 Reviewer characteristics

The study consisted of 556 reviewswith the reviewers’ mean TripAdvisor contribution of 40.78 (Min = 1, Max = 4239, SD = 209.83). The mean score ratings for street food tour experiences was 4.92 (Min = 1, Min = 5, SD = 0.42). Based on the provided personal information, half of the reviewers (51.3%) identified their travel companion and almost half of the reviewers (45.9%) revealed their country of residence. For travel companion, the results showed that almost a quarter (24%) traveled as a couple, followed by alone (13.10%), friends (10.3%), family (7.1%), and business colleagues (0.8%). Regarding country of residence, the top five countries joining the street food tours were from USA (13.2%), UK (12.1%), Australia (4.8%), Canada (2.5%) and The Netherlands (2.4%) respectively.

3.2 Word frequency analysis

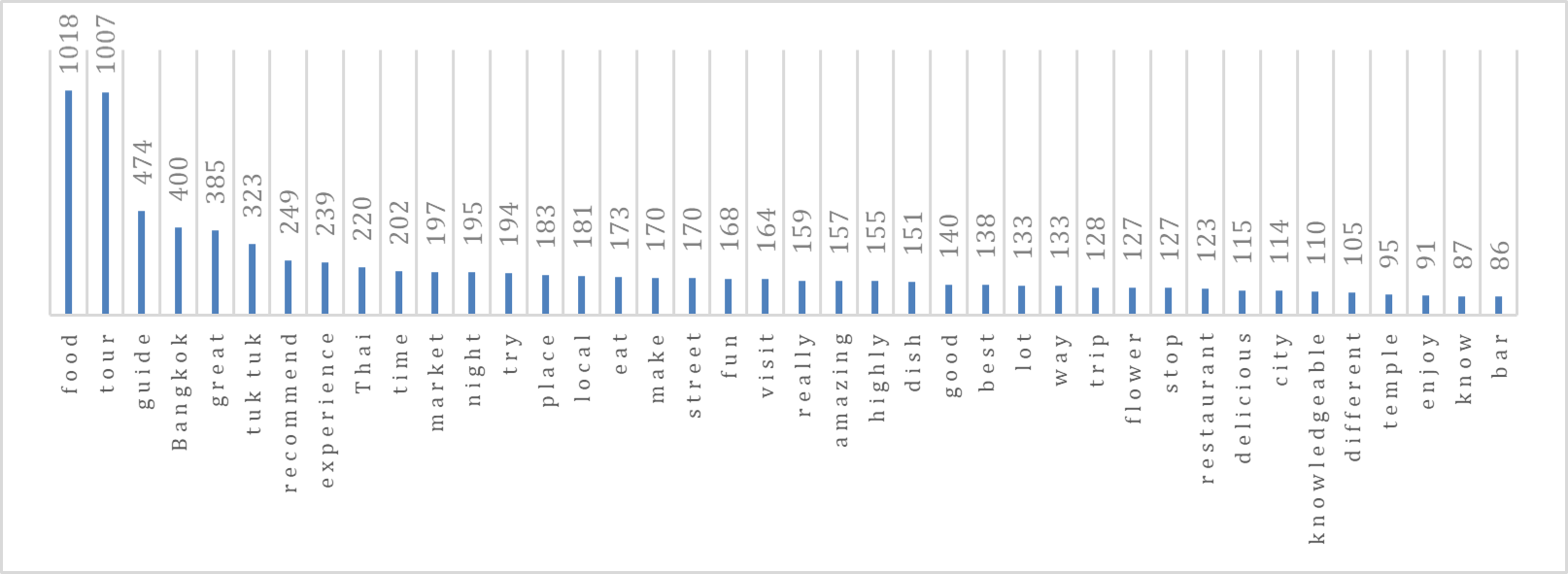

The first step was to check the words that frequently appeared in the reviews. Word frequency represents the key aspects of the reviews. The top ten frequently mentioned words as illustrated in Figure 3 are ‘food’, ‘tour’, ‘guide’, ‘Bangkok’, ‘great’, ‘tuk tuk’, ‘recommend’, ‘experience’, ‘Thai’ and ‘time’ respectively.

Based on the literature review and the themes emerging from the data, the experience economy model was used as a theoretical framework for analyzing the data. The top 40 frequently mentioned words can be organized into seven themes as follows; 1) education 2) esthetic, 3) escapist, 4) entertainment, 5) exploration, 6) satisfaction and 7) behavioural intention. The themes and frequently mentioned words can be grouped as shown in Table 1.

3.3 Co-occurrence network analysis

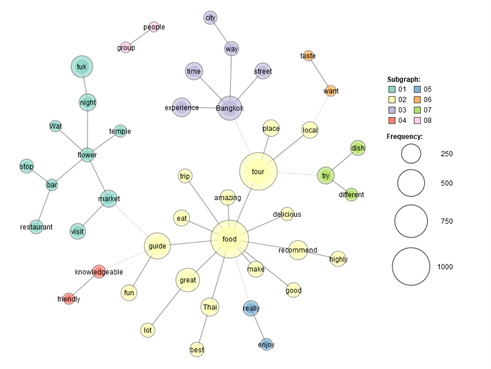

Co-occurrence network is a powerful analysis method to indicate the relationships between words and ideas in a text corpus (Zheng et al. 2020). This study used nouns, verbs, adverbs and adjectives to create a co-occurrence network from 60 pairs of the most strongly occurring words. Based on Jaccard coefficients, the size of the nodes represents the word frequency while thickness of connector line represents the strength of co-occurrence or an association between the extracted words (Higuchi 2016). Figure 4 presents the co-occurrence network analysis.

Figure 4 shows that there are eight subgraphs emerging from the analysis. The largest word community (yellow subgraph - 02) comprises of two major words: ‘food’ and ‘tour’. The word ‘food’ is strongly connected to ‘guide’, ‘great’, ‘Thai’, ‘make’, ‘good’, ‘recommend’, ‘delicious’, ‘amazing’, trip’ and ‘eat’. The word ‘tour’ in particular is strongly associated with ‘local’ and ‘place’. Referring to Table 1, the words associated with ‘food’ fall into the following five themes; education, escapist, exploration, satisfaction and behavioural intention. The two words connected with ‘tour’ mainly reflect an exploration theme. There are other smaller word communities that can further explain food tourism experiences. The word ‘Bangkok’ (purple subgraph - 03) is connected with ‘experience’, ‘time’, ‘way’ and ‘street’ while the word ‘try’ (green subgraph – 07) is associated with ‘different’ and ‘dish’. These associated words are categorized in three main themes including education, escapist and exploration.

3.4 Key words in context

Key words in context (KWIC) or concordance is further used to examine how words in the themes appear in text data. Findings are organized according to the emerging themes and their associated words as shown in Table 1.

3.4.1 Education

Street food tours provided opportunities for tourists to learn new cuisine, traditions and heritage in various dimensions. Food tours were perceived as great ways to introduce ‘unfamiliar’ and ‘different’ dishes. Tourists could engage in different food activities such as ‘preparing’, ‘cooking’ and ‘eating in local food places’. Table 2 presents reviews related to education.

Through street food tours, tourists gained ‘cultural and culinary insights’ such as ‘history behind the food’, ‘non-tourist food locations’, ‘food sharing culture’, ‘cooking tips’ and ‘Thai customs’. A tour guide appeared to play an important role in educational experience. The reviewers were satisfied with the guide who was ‘knowledgeable’, ‘informative’, ‘friendly’, ‘fun’, ‘passionate’, ‘proud of own culture’ and ‘professional’.

3.4.2 Esthetic

Regarding esthetic experience, street food tours immersed touristsinto a unique destination environment and dazzled them with all senses including tastes, smells, sights and sounds, ambience and atmosphere. Table 3 presents reviews related to esthetic experience.

From Table 3, sightappears to be the most frequently mentioned aspect of esthetic experience. Tourists experienced various sights during street food tours either by walking or taking the local transportation. The top three frequently mentioned sights were ‘Bangkok’, ‘market’ and ‘night’. Besides the local food, the destination setting and environment can be the distinctive and powerful esthetic dimensions of the street food tour experiences.

3.4.3 Escapist

This particular aspect of the escapist experience let the tourists be a ‘new self’ from their usual dining customs and get away from their routines. By joining street food tours, tourists could experience new cuisine and environments which were unlike their everyday life as described in Table 4.

Street food tours wereperceived as a good chance to try ‘something out of the ordinary’. Street food tour activities provided enjoyment, excitement and opportunities to do something exciting. The tourists were exposed to a completely new dining environment. Along the way, the tourists visited ‘hidden places’ as well as experienced different kinds of ‘Michelin starred street food vendors’. One review (R93, Canada) described the food tour experiences as ‘enlightening and great fun.’

3.4.4 Entertainment

Street food tours allowed the tourists to visit places along the journey as well as to join other unexpected activities which further enhanced their memorable experiences. Activities included in the street food tours were described as ‘entertaining’, ‘fun’, ‘exciting’, and ‘whirlwind adventure’. Table 5 shows examples of reviews related to entertainment.

Street food tours’ activities led the tourists to a unique and lively food destination environment which was perceived as ‘a live entertainment’. Examples of the activities mentioned in the reviews were ‘walking through endless trail of street food’, ‘watching the food being cooked in the street’ and enjoying ‘a great view of Bangkok landmarks at night’. One review (R.203, Canada) depicted a street food tour as ‘excellent combining culture and food highlights when the city came alive’.

3.4.5 Exploration

Street food tours provided a fifth realm of food tourism experience, exploration, which further complemented the four realms of experience economy model. Tourists could enjoy eating the food like locals, try authentic food specialties and experience the local food heritage alive as described in Table 6.

Street food tours captured the real city atmosphere and genuine local way of life. They offered various exploration dimensions including ‘going where the locals go for their food’, ‘eating like locals’, ‘cooking local food’, ‘joining local activities’, ‘using local transportation’ and ‘attending local festivities’. The term ‘authentic’ was mentioned in various contexts such as ‘food’, ‘place’, cooking’, ‘taste’ ‘experience’ and ‘Thai’. One review (R.425, New Zealand) summarized the exploration experience as follows:

“Hands down. We wouldn’t have tried any of these places if it wasn't for this tour. …sampling market food, showcasing the history of some the streets, how the food was made and catching a ferry and a bus! This was a trip about authentic Thai food which keeps the Thai culture alive.”

3.4.6 Satisfaction and behavioural intention

Street food tours provided various dimensions of experience such as education, esthetic, escapist, entertainment and exploration. The combination of these dimensions provided authentic and memorable experiences that further led to tourist satisfaction and behavioural intention. Table 7 shows reviews related to satisfaction and behavioural intention.

Street food tours were mentioned as ‘a highlight of time spent in Bangkok’, ‘a favorite activity’, ‘an unforgettable culinary experience’ and ‘the best experience in Bangkok’. Tourist satisfaction led to different aspects of behavioural intentions. It also led to positive e-WOM for fellow tourists on online booking platforms. Furthermore, the satisfied tourists showed a tendency to ‘re-visit’ the destination as well as to ‘re-join’ the street food tours.

4. DISCUSSION

The four realms of experience economy model (Pine and Gilmore 1999) including education, esthetic, escapist and entertainment have been directly applied as a theoretical framework in recent food tourism studies on the assumption that it can fully explain food tourism experiences. To date, the said model has hardly been examined especially in the area of street food tours which have gained popularity among food tourists.Laing and Frost (2015) argued that food tourism experience involved another fifth realm, an exploration, which is not included in the said model. Furthermore, such an argument has not yet been examined. Despite the growing popularity of food tours in many leading food destinations, studies looking into this specific tourism activity in terms of satisfaction and behavioural intention are still very limited (Ozcelik and Akova 2021). Considering the existing research gaps found in food tourism literature, this study aimed to examine the experience economy model in the context of street food tours to understand the tourist experience, satisfaction and behavioural intention.

The results revealedthat there were five dimensions relating to the street food tour experiences. The study provided empirical evidences to supportGetz et al. (2014) that the four realms of experience economy model could be applied as a theoretical framework to explain street food tour experiences. First, educational aspects of street food tours provided opportunities to learn new cuisine, traditions, heritage and culture (Ellis et al. 2018). Street food tours could possibly be used for introducing local food which is unfamiliar to the tourists. Consistent withCaber et al. (2018) andKattiyapornpong et al. (2022), tour guides played important roles in memorable experience and satisfaction by sharing knowledge and the history behind the food with the tourists, thus making the tours fun and informative. Second, esthetic experiences came from the tourists’ sensory exposure to tastes (Kim and Eves 2012), sights, sounds and smells of the destination environment, ambience and atmosphere. For street food tours, sight appeared to be an important factor for the esthetic experience. Street food tours revealed various dimensions and settings of Bangkok either by walking or using local transportations. Third, escapist experiences immersed tourists into a new dining environment and customs which were different from their normal routines. A street food tour was regarded as a food adventure by doing something fun, exciting and out of the ordinary. The results revealed that street food tours provided tourists the opportunities to be new self and exposed them to a completely new world. Fourth, entertainment aspects of street food tours brought fun, enjoyment and excitement through vibrant destination settings and activities included in the street food tours such as riding on the tuk tuk or watching the food being prepared and cooked in the street. In line withMak et al. (2017), the tourists regarded these local food activities as live entertainments. Insights into street food tour experiences further extended the application of experience economy model in the past food tourism research (Soonsan and Somakai 2021;Lai et al. 2021;Suntikul et al. 2020). These findings would provide better understanding of street food tourism experiences and implications for destination marketing.

Besides the four realms of experience economy model, the study also provided empirical findings tosupportLaing and Frost (2015)’s argument on the application of the model in food tourism that street food tour activities could provide another realm of experience, an exploration, with emergent learning (eating like locals), authenticity (local food specialties and ingredients) and sustainable livelihood (local food heritage setting and atmosphere). This particular fifth realm clearly indicated that street food tours provided tourists with an authentic experience of local dining in the real destination settings and atmosphere. A sense of authencity (Mhlanga 2020;Lunchaprasith and Macleod 2018) in particular is a distinct and unique element of street food tour experiences in a form of food pilgrimages (Laing and Frost 2015;Long 2006). The findings on the emerging fifth realm, an existing argument in food tourism literature, is valuable to advance the present knowledge of street food tour experience and the extended application of the experience economy model.

This study also revealed several insights into the role of street food tours on tourist satisfaction and behavioural intention. Consistent with past studies on local food dining experiences (Lai et al. 2021;Choe and Kim 2018;Bianchi 2017;Seo et al. 2017), positive street food tour experiences could also lead to satisfaction and behavioural intention. Tourists who were satisfied with the street food tours expressed their intention to re-visit the destination, re-join the street food tours and recommend to others. In other words, positive street food tour experiences could potentially become the tourism motivation to re-visit the destination (Hall and Sharples 2003). Furthermore, satisfaction with all dimensions of street food tour experiences could build a special bond between the tourists and the destination (Mitchell and Hall 2003) that can enhance positive destination image and create destination loyalty.

5. CONCLUSION AND IMPLICATIONS

Food tourism literature is still in its developing stage and there are assumptions and arguments that need to be tested. This study made an attempt to examine whether and how the experience economy model could explain street food tour experiences. The findings suggested that the four realms of the experience economy model could be applied as a theoretical framework to explain street food tour experiences. However, the findings further supportedLaing and Frost (2015) that there was an emerging fifth realm, exploration, which the experience economy model cannot fully explain street food tour experiences. The results further indicated that positive street food tour experiences led to satisfaction, intention to re-visit the destination, intention to re-join the street food tours and willingness to recommend to others.

The presentstudy has made theoretical contributions to fulfill the research gaps in food tourism literature. First, it investigated an assumption in food tourism literature (Ellis et al. 2018;Getz et al. 2014) that food tourism experience was grounded in the four realms of experience economy model (Pine and Gilmore 1999). Second, this study further examined an existing argument in food tourism literature (Laing and Frost 2015) that food tourism experiences also offered an exploration dimension. Third, the study also provided the findings on the role of street food tours on satisfaction and behavioural intentions. Fourth, the study focused on specific food tourism activities and the actual tourist experiences which are still lacking in the food tourism arena (Ozcelik and Akova 2021;Okumus 2021;Cifci et al. 2021).

This study also provided methodological contributions to the field of food tourism research. The study used online reviews, Big data in tourism research, (Correia and Kozak 2022;Bigne et al. 2021) to provide better insights of realistic street food tours’ consumption and evaluation (Sangkaew and Zhu 202). The study also adopted a text mining data analysis recently introduced into tourism studies (e.g.Chen and Tussyadiah 2021;Padma and Ahn 2020;Hu and Trivedi 2020) to identify patterns of street food tour experience and behavior. Furthermore, the study provided key variables for future quantitative studies on the role of street food tours on experience, satisfaction and behavioural intention.

The study offers several recommendations for tourism practitioners. First, street food tours can be used as a marketing strategy to deliver unique, authentic and memorable cultural experiences. Second, the four realms of economy experience model as well as an exploration dimension can be applied as a guided framework to further develop street food tour experiences. Third, local food, local people, guides and destination environment are regarded as the important factors enhancing the memorable experience of street food tours. A strong collaboration of various business partners is crucial for the success of street food tours (Andersson et al. 2017). Fourth, street food tours can familiarize tourists with local food as well as to enhancing positive attitudes towards food and destinations. Lastly, street food tours can be an alternative marketing strategy to differentiate tourism products, increase satisfaction and behavioural intention as well as enhance destination loyalty.

Food tourism research in Asia is still in its developing stage and there are plenty of avenues for further studies. Future researchers would be encouraged to conduct qualitative studies such as in-depth interviews with the tourists joining the street food tours. Relevant theories beyond the experience economy model can also be examined to further explain food tourism experience, satisfaction and behavioural intentions.