INTRODUCTION

An uninterrupted life cycle is observed in Anatolia from the Paleolithic period to the present day thanks to the location of the Anatolian geography, its fertile soils, and climatic diversity. Therefore, Anatolia, a crucial part of World History, presents data from a broad perspective regarding cultural heritage. Çorum settlement, which constitutes the study area, has a rich portfolio in terms of both natural resources and cultural assets. According to its period, each traditional structure and structuring reflects the historical and cultural values of the life of the society that produces itself. Çorum and its environment, which have been home to various civilizations in history, are also essential for archeotourism’. The destination is effective in the cultural tourism preference of the visitors with the cultural heritage of the Hittite civilization, unearthed ruins, and the artifacts exhibited in the museums (Değirmencioğlu, 2010). Hattis is the capital city of the Hittite empire. Including the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) World Heritage List (UNESCO, 2022) and Yazılıkaya, Alacahöyük, Hüseyindede, Eskiyapar, Resuloğlu excavations shed light.

It is possible to trace many civilizations that have dominated the region. The existence of the Hittite state, which established sovereignty over almost all of Anatolia, seized the Mesopotamian trade routes (Sir Gavaz, 2007), and became a world state, is influential in the historical richness of the region and the formation of world cultural history. Hattusa, which is the first organized state and reflects the richness of Hittite civilization, sheds light on Anatolian archeology since it is the lands of both Alacahöyük, Hüseyindede, Eskiyapar, Resuloğlu settlements and Seljuk and Ottoman periods and artifacts from Phrygian, Roman, Byzantine (Yıldırım & Sipahi, 2003; Sipahi, 2011; Süel & Süel, 2011; Şahin, 2018).

Çorum has natural beauty in addition to its historical and cultural structures. Kargı Abdullah Plateau Nature Park, Çatak Nature Park, Siklik Nature Park, and Recreation Area; Kargı Plateau, Abdullah Plateau, Bayat Kunduzlu and Kuşcaçimeni Plateaus, İskilip Plateau, Osmancık Başpınar Karaca Plateau; İncesu Canyon, Osmancık Koyunbaba Bridge; Örencik Kızılcaoluk waterfalls and other intangible and tangible cultural heritage items is a top tourism center located in Çorum. The Hittite Road was formed by using ancient migration and caravan routes in the triangle of Boğazköy-Hattusa ruins, being on the UNESCO World Heritage list, and another vital ruin of Çorum, Alacahöyük-Şapinuva. Also, “Gastronomy and Walking Trail,” an ecotourism study that brings together nature, history, and culinary culture for the first time in Turkey, offers an experience that brings together the route and taste, where various activities are carried out together in Çorum. (Çorum Governorship, 2020). Çorum has mosques, inns, castles,

bridges, and baths from e Seljuk and Ottoman periods, as well as many Archeological attractions (İpek et al., 2008), and it is a significant archaeology tourism destination in the Republican period (Günay, 2007). Çorum also has natural attractions such as plateaus and canyons and historical-cultural attractions. For example, there are rafting and trekking trail routes in Şapinuva-İncesu canyon, one of the region’s most critical natural beauties, surrounded by cliffs. It is also possible to observe the reliefs carved into the rocks on the slope. “İncesu Canyon Culture Park,” being a part of the Hittite Road, is one of the critical centers for nature lovers, mountaineers, bird watchers, and archeo-tourists (Gülersoy & Gülersoy, 2016). Archeological sites have become important tourist attractions with the development of modern tourism understanding (Willems & Dunning, 2015). Archeotourism’, which aims to promote and market Archeological heritage elements to tourists, has become a type of tourism with increasing demand (Ross et al., 2017). Archeotourism’, generally considered cultural or heritage tourism (Mazzola, 2015; Pawleta, 2019), is also defined as a type of heritage tourism because it is motivated by archeology (Howard, 2003).

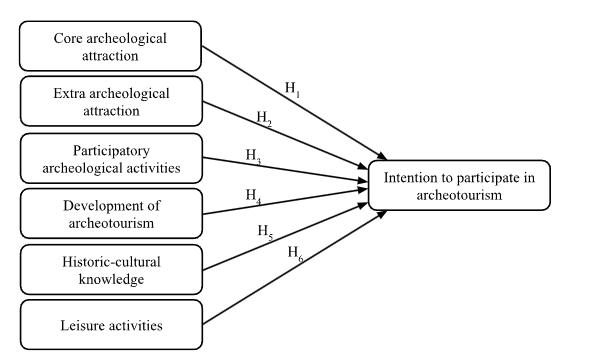

We aim to examine the effect of archeotourism’’s attractive motivational factors on the intention to participate in archeotourism’. Studies show that archeotourism’ motivation factors impact the intention to participate (Som et al., 2012). Tourists are interested in researching and examining the main Archeological attractions (Lwoga & Mwankunda, 2020). For example, sightseeing tours are crucial in visiting archeotourism’ destinations. Traditional experiences are essential for touristic development (Mickleburgh et al., 2020). Some studies (Dans & González, 2019; Kherrour, Hattab & Rezzaz, 2020) show that historical and cultural identity affects tourism mobility in archeotourism’. Archeotourism’ Development of the Destination affects the visit intentions (Mulyantari et al., 2021). Li and Qian (2017) expressed that archeotourism’ is crucial to tourism development. Also, Johnson (2011) expressed that archaeology has traditionally had an influential association with leisure activity. Martínez-Hernández, Mínguez, and Yubero (2021) found out that archeotourism’ improves its tourist attraction if it is enriched with leisure activities.

The two primary research questions that we try to address in the present study are: 1) What is the effect of archeotourism’ motivation factors on the intention to participate in archeotourism’ in Çorum. 2) what is the effect of sub-factors as extra Archeological attractions, core Archeological attractions, leisure activities, Archeotourism’ development of the destination, historic-cultural knowledge and participatory Archeological activities on intention to participate in archeotourism’. To summarize, the present study empirically validates a model that archeotourism’ motivation factors positively affect the intention to participate in archeotourism. This paper investigates the effect of the attractive motivational factors of archeotourism’ on the intention to participate in archeotourism’ in Çorum. The paper has a unique value because of the absence of archeotourism’ attractive motivational factors. We used determinants such as core Archeological attraction, extra Archeological attraction, participatory Archeological activities, destination archeotourism’ development, leisure activities, and historical-cultural knowledge based on the work of Rodríguez and Perez (2022). Depending on these sub-factors, the intention of tourists to participate in archeotourism’ in Çorum was evaluated.

LITERATURE REVIEW AND HYPOTHESES DEVELOPMENT

Motivation is the internal impulse that arouses and directs the desire to perform any behavior in individuals (Murray, 1964: 378; Erkol Bayram, 2017). Travel motivation can be defined as the factors that prepare and encourage people before going on a trip from a tourist perceptive (Pizam et al., 1979). Therefore, it is essential to understand the reasons and behaviors for the travel experience (Horneman et al., 2002). There are many studies on tourist motivation (Yoo et al., 2018; Kim and Lee, 2020; Egger et al., 2020). According to Menor-Campos et. Al (2020), four dimensions are related for tourist motivation: these classifications refers to alternative, cultural, emotional, and patrimonial tourists. One of the most well-known papers, Dann (1977) and Crompton (1979), conducted on the motivations of tourists, the “push” and “pull” factors. Push and pull factors are the most widely used theoretical approach for determining and analyzing tourist motivations (Antara & Prameswari, 2018; Subadra, 2019; Su et al., 2020).

The most common attractive factors are historical sites, historical attractions, and tangible and intangible cultural heritage sites in the literature (Kanagaraj & Bindu, 2013; Mohammad & Som, 2010; Yiamjanya & Wongleedee, 2014). Natural heritages are another vital dimension after historical heritages as attractive factors in destinations (Khuong & Ha, 2014). Studies on push and pull factors listed relaxation, novelty, socialization, knowledge seeking, prestige, and family/friend association as driving motivation factors (Lin, 2014; Linh, 2015; Nikjoo & Ketabi, 2015). Cultural values, nature, historical sites, activities, safety, climate, shopping, and hygiene are attractive motivation factors (Hani, 2016; Nikjoo & Ketabi, 2015; Yiamjanya & Wongleedee, 2014).

Tourism destinations and each type of tourism have their different elements of attraction. For example, people can find much attractiveness to travel motivations for an archeotourism-rich destination. Rodríguez and Perez (2022) determined attractive motivation factors of archeology tourism as six dimensions in Spain. Core Archeological attractions are such as Open air and underground Archeological sites, caves, rocks and shelters, museums, or Archeological collections. Also, Çorum has several core attractions Archeological attractions such as Hattusa, Yazılıkaya, Alacahöyük, Şapinuva, Hüseyindede, Eskiyapar, Resuloğlu ruins, Boğazköy Museum, Alacahöyük Museum, Çorum Museum, Seljuk and Ottoman structures.

The Hittites influenced the Anatolian peoples for a long time as a military, technological, economic, and cultural power being a central kingdom in a short time. The military, civil and religious architecture of the Hittites can be seen in the research

area. The monumental temple complexes, civil settlements and storage areas, enormous defense system and tunnels called postern encountered in the Hittite capital Boğazköy Hattusha, as well as the Lion Gate, decorated with reliefs and sculptures showing fine stonework, the Sphinx Gate and the King Gate, reflect the magnificence of the city (Schachner, 2019). About 2 km northeast of Boğazköy, Yazılıkaya, the sacred place of Hattusha, exhibits the official pantheon and functions as an open- air worship center of Hittites (Yiğit et al., 2016). Alacahöyük, identified with Arinna located in the Alaca region. Ortaköy- Şapinuva, which is the capital and religious center of Hittite, was used as a “military base” as well as being an important center in terms of politics, economy, and culture (Süel & Süel, 2011). Eskiyapar, an important Hittite center, continued its existence in the Old Hittite, Middle Hittite, and Hittite Empire phases from 3,000 BC to the Roman and Byzantine periods (Sipahi, 2011). Cult vases belonging to the Old Hittite Kingdom Period are among the rarest examples of Hittite art unearthed in the Hüseyindede excavations (Yıldırım & Sipahi, 2003). Laçin Kapılıkaya and Gerdekkaya rock tombs dating to the Hellenistic period; The cradle roof and the temple facade architecture reflected on the rock and the Iskilip rock tomb dated to the Roman period (Çorum Governorship, 2010) provide information about the burial traditions in the region. The artifacts recovered from the excavations in the area are exhibited in Boğazköy, Alacahöyük, and Çorum museums with rich collections. In particular, the Hittite period’s cuneiform tablets reveal the era’s social structure, special issues, law, and administrative system. Alacahöyük royal tomb gives information about burial customs. Ceramics, glass, and metalworks belonging to the Phrygian, Hellenistic, Roman, and Byzantine periods are exhibited in thematic and chronological order. The period in which the works are dated, the areas of use, and the drawings make it easier to understand.

The rich archeology of Çorum makes it an important destination. Gürsu (2013) states that domestic tourists positively perceive museums in Çorum. According to Günay (2007), the study of the essential Archeological elements of Çorum (museums, ruins, etc.) attracted the attention of tourists, and they had positive attitude after visitation. Şahin (2021) determined that museums and ruins in Çorum are essential elements in terms of tourism. Based on all this information, the following hypothesis was formed;

H1a: Core archeological attraction effect positively intention to participate in archeotourism.

Additional motivating elements are used in the context of archeotourism in tourism destinations. The second of the archeological tourism motivation factors; are extra archeological attractions and It offers opportunities such as dramatized visits to Archeological sites, light and sound shows, festivals and concerts, historical recreation activities, established fairs, and restaurants with historical, traditional, and local menus. There are examples as Archaeology Film Festival, World Hittite Day, Ortaköy-Şapinuva-İncesu Canyon Culture and Art Activities, Örencik Village History and Culture Festivals, Once Upon a Time in Çorum, Hattusha Tourism Days, Boğazkale Culture Festival, Culture, and Promotion Festival, International Hittite Fair and Festival, Hattusa Tourism Days. Various services are provided to visitors using technological innovations in Çorum Archaeology Museum within extra Archeological attractions. Technical facilities are used in museum sections. After Android applications have been used widely, there is access to the museum’s transportation, contact addresses, floor plans, tags of the exhibited works, and visual contents of the results in Turkish and English languages. The exhibitions can also be followed through the mobile application. Audio guidance system devices are available for visitors who cannot visit the museum with a guide. There is an electric handicapped elevator that provides access to all sections from the ground floor of the museum to the fourth floor. Interactive systems were produced for the Çorum Archaeology Museum with the support of the Middle Black Sea Development Agency (OKA). Excursion in the ancient city of Hattusa with the “Chariot Simulator” in the museum; With the “Burial Ceremony,” information about traditions and objects and “3D Vase Analysis” applications were seen in the museum (Reo-Tek, 2022). Applications videos for Çorum Museum and other museums can also be viewed on the Reo-tek site. Festivals and symposiums organized by local governments and associations promoting the historical and cultural aspects of Çorum are essential to increase the recognition of the Hittite civilization.

According to Esichaikul and Chansawang (2022)’s study on tourists visiting the Historical Park in Sukhothai Province, the sustainability of core and extra Archeological heritage attractions impacts the intention to participate. Similarly, Ibimilua (2009) stated that one of the factors affecting the intention to join tourists visiting Ekiti state in Nigeria is core and extra Archeological. In light of this information, the following hypothesis was formed in the research;

H1b: Extra archeological attraction effect positively intention to participate in archeotourism.

Participatory Archeological activities were examined as the third dimension in the attractive motivation factors of archeotourism. Experiences such as Archeological projects where volunteers can participate one-on-one and the opportunity to be included in experimental Archeological activities can be explained as the attractiveness of participatory Archeological activities. Education in the museum paved the way for an interdisciplinary active learning path with the “Everyone to the Museum” project, which was prepared within the framework of OKA’s “Small-scale infrastructure development, protection and improvement of cultural, touristic values and ecological balances” project. Therefore, practical training workshops in projects within sustainable museum education are essential to instill awareness of protecting cultural assets (Yılmaz, 2015). The “Hittite village project” building, supported by OKA within the scope of the “2016 financial support program for small-scale infrastructure investments for tourism development, “ is opposite the Boğazköy Museum. The building structure was made visually based on the Hattusa fortification system. A rectangular courtyard opens from the plan in the middle of the building. The lower floors of the building surrounding the courtyard are used as production and sales points. There are classroom and presentation rooms on the upper floors. “Strengthened Cooperatives, Strong Women Project” and “Puduhepa Women Entrepreneurs Production and Development

Cooperative” started to use the rooms of the building in 2020. Training on antique products for tourists provides the opportunity to engage in participatory Archeological activities for tourists. Ross et al. (2017) concluded that participatory Archeological activities positively affect the level of participation in archeotourism within tourism experience. Similarly, Thomas (2014)’s a study on tourist experiences within the scope of archeotourism’ in England, Scotland, and Wales concluded that experience in Archeological activities affects the intention to participate. In light of this information, the following hypothesis was formed in the research;

H1c: Participatory archeological activities effect positively intention to participate in archeotourism.

As the fourth dimension in the attractiveness as the motivational factor of archeology tourism, Archeotourism development of the destination, such as destination awareness with Archeological remains and artifacts, being on the famous and well-known archaeology routes of the region are discussed. Finally, as the fifth dimension, Historic-cultural knowledge was included as trips with tour guides, the opportunity to meet with new cultures, and observation of the destinations’ historical and cultural heritage. Hattusa, included “World Heritage List” by UNESCO, is a tourism center in Çorum destination. Yazılıkaya and Alacahöyük have also visited areas due to their proximity to the Hattusha. There are mosques, inns, castles, bridges, and baths from the Seljuk and Ottoman periods, besides Archeological attractions and natural beauties such as plateaus and İncesu Canyon in Çorum. Rodríguez and Perez (2022) determined that Historic-cultural knowledge and Archeotourism development of the destination affect the intention to participate. Similarly, according to Brida et al. (2016 research on tourists visiting Vittoriale in Lake Gardo, a known Italian tourism center, Historic-cultural knowledge and archeotourism development of the destination affect intention to participate. In light of this information, the following hypotheses were formed in the research;

H1d: Historic-cultural knowledge effect positively intention to participate in archeotourism.

H1e: Archeotourism development of the destination effect positively intention to participate in archeotourism.

The sixth and last dimension of the attractive motivation factors of archeology tourism is leisure activities such as tasting local gastronomic products, offering the opportunity to shop, enjoying nature, and having unique entertainment for children, etc. Leisure activities attractions include nature parks (Kargı Abdullah Plateau Nature Park, Çatak Nature Park, Siklık Nature Park), plateaus (Kargı Plateau, Abdullah Plateau, Bayat Kunduzlu Plateau, Kuşcaçimeni Plateau, İskilip Plateau, Osmancık Başpınar Karaca Plateau), waterfalls in Çorum. Leisure is time apart from working life and all physiological needs (Gül, 2014: 8). Leisure activities are chosen by people voluntarily. Leisure activities for archaeo-tourism in Çorum are spread over a wide area. One hundred eighty-five sites in Çorum are 182 Archeological and three urban sites. There are also five tumuli and two rock tombs (Ministry of Culture and Tourism, 2022). Historical and Archeological sites are among the most frequently visited attractions by tourists (Günay, 2007). There are some examples as Çorum Museum, Alacahöyük Ruins, Boğazköy Museum, and Yazılıkaya Hattusa Ruins (Çöpür & Uysal, 2003). According to research, Archeological sites and museums belonging to the Hittite period are the most visited attractions. This result proves that Çorum is an essential destination for archeotourism’. In addition, the existence and diversity of leisure activities are effective in the choice of destination (Navratil et al., 2018). According to Rokicha- Hebel et al. (2016) study on tourists visiting historical touristic places in Poland, the diversity of leisure activities in destinations effect the intention to participate. Similarly, Navratil et al. (2018) determined the impact of leisure activities on visit intention in research on tourists visiting cultural heritage sites in the Czech Republic. In light of all this information, the research developed the following hypothesis.

H1f: Leisure activities effect positively intention to participate in archeotourism.

Figure 1: Research Model

The research population consists of tourists over the age of 18 who visited Çorum before or for the first time. There is no data on the number of tourists constituting the research population and gathering information from the whole population is not easy. Hence, it is used as a sample to represent the population due to cost and time. It was determined that at least 384 participants (Sekaran, 2003) were from the total population. Ethics committee approval was obtained from Ordu University Social and Human Sciences Research Ethics Committee on 30.03.2022 with numbered 04 and decision numbered 2022-43 to declare collecting data ethically. Research data were collected face-to-face from 470 participants using a convenience sampling method questionnaire between July and August 2022 in Çorum Türkiye.

Measures

The questionnaire form consists of two parts. The first part includes categorical questions about participants’ demographic characteristics. In the second part, items belonging to 6 sub-factors used to explain the archeotourism incentives are used. The archeotourism incentives sub-factors were adapted from the study of Rodríguez and Perez (2022) and revised by evaluating from an Archeological point of view in the province of Çorum, which covers the research area. In this context, extra Archeological attractions (EArcheo) (four items), core Archeological attractions (CArcheo) (four items), leisure activities (LA) (six items), Archeotourism development of the destination (DArcheo) (four items), historic-cultural knowledge (HCK) (three items), and participatory Archeological activities (PArcheo) (two items) items of sub-factors are included. In addition, three items of the intention to participate in the archeotourism (ATnyt) scale are used, adapted from the study of Rodríguez and Perez (2022). We used a five-point Likert scale rating from “1” strongly disagree to “5” strongly agree. In addition, the translation of the scale items used in the research was done twice to avoid any semantic shift. First, after it was understood that there was no semantic shift, the archeotourism incentives scale items were revised by authors considering the archeological assets of Çorum. Then, the questionnaire form was sent to seven experts for their evaluation. Thus, the content validity was completed before the scale items were used.

Data Analysis

We used SmartPLS statistical programs to test the research model. The validity, reliability tests, and structural equation modeling (SEM) analysis of data coded in the SPSS statistical program were performed in the SmartPLS statistical program. The relationship between the observed and unobserved variables in the studies and the model suitability can be tested with the SEM model. Two different methods can be mentioned in SEM applications. The first of these methods is covariance-based structural equation modeling (CB-SEM), and the other is partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). The normal distribution is not evaluated in the SmartPLS statistical program’s analyses (Wong, 2013).

The purpose of using the SmartPLS statistics program is to provide all the data in the scale evaluation process simultaneously and to measure the formative or reflective status of the items in the scale. Confirmatory tetrad analysis (CTA) is applied to determine the scale type. Since the number of items of the participatory archeological activities, historic-cultural knowledge, and intention to participate to archeotourism scales was less than four during the CTA analysis stage, the analysis was performed by adding the indicator (items) of any variable (CArcheo1 and CArcheo2 were used randomly) to the relevant scales (Bollen & Ting, 1993). Since 25 indicators are created per structure in CTA analysis, at least four are needed. Two additional indicators have been added because participatory archeological activities have two indicators, and one additional indicator has been added to the others because it has three indicators. Confidence intervals calculated with Bonferroni correction (adjusted confidence interval) were examined in the CTA analysis. While leisure activities, extra archeological attraction, archeotourism development of the destination, and intention to participate to archeotourism scales were in the reflective structure, core archeological attraction, participatory archeological activities, and historic-cultural knowledge scales were in the formative structure. As a result of all these evaluations, the PLS-SEM method was used while performing the structural equation model analysis in the SmartPLS statistical program.

During the validity and reliability analysis of the reflective scales, Cronbach Alpha (α) analysis was performed to determine the reliability coefficient. Composite reliability (rho_c and rho_a) was determined to calculate internal consistency, and averaged variance extracted (AVE) was determined for convergent validity. Outer loadings (λ) were calculated for indicator reliability. Fornell Larcker criterion, Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio (HTMT), and cross loadings were calculated for discriminant validity. In addition, standardized root means square residual (SRMR), normed fit index (NFI), d_G, d_ULS, and GoF (Goodnes of fit) values were calculated as research model goodness of fit. During the validity and reliability analysis of the formative scales, convergent validity, linearity, statistical significance, and level of relevance were examined.

Firstly, the participants’ demography was examined in the study. 21.3% are 55-64, 21.1% 45-54, 19.1% 35-44, 17.7% 25-34,

12.6% 65 and over, and 8.3% are between 18-24. 56.2% are female, and 43.8% are male. 41.3% of the participants said they visited Çorum for the first time, 38.5% 2-4 times, 15.7% 5-7 times, and 4.5% eight or more times. 16.4% of the participants were undergraduate, 21.5% high school, 19.1% doctorate, 15.1% graduate, 14.3% associate degree, and 13.6% primary education. 28.1% of the participants are in the range of 10001-15000 TL, 25.5% are in the range of 15000 TL and above, 22.3% are in the range of 8001-10000 TL, 14.5% are in the range of 6001-8000 TL and 9%0. have income in the range of 4501-6000 TL (see Table 1).

Table 1: Participant Profile

Measurement Model Assessment

When the Cronbach Alpha reliability coefficient of the reflective scales was calculated, the values of the scales were in the range of 0.872-0.961. The values in this range show that the scale items are reliable and are very good because the scores are higher than

0.70 (Hair et al., 2017). When the rho_a was calculated, the values of the scales were in the range of 0.888-0.963. Values obtained in this range indicate that the scale items are reliable and that the scores are higher than 0.70 (Dijkstra & Henseler, 2015).

Table 2: Validity and Reliability

CArcheo= Core archeological attraction, EArcheo= Extra Archeological Attraction, PArcheo= Participatory archeological activities, HCK= Historic-cultural knowledge, DArcheo= Archeotourism development of the destination, LA= Leisure activities, Int= Intention to participate to archeotourism

The rho_c was calculated for internal consistency. The values of the scales were between .922 and .972 after calculating rho_c scores. The values in this range show that items have internal consistency and are accepted since scores are higher than .60 (Bagozzi & Yi, 1988). Outer loadings of the items belonging to each scale were higher than .50 As a result of the factor analysis to determine the construct reliability (Kaiser, 1974). The goodness of fit values was calculated before the structural equation modeling analysis.

Table 3: Model goodness of fit values

|

Criteria |

Model Scores |

Critical Value |

|---|---|---|

|

Chi-Square ( X2 ) |

2320.000 |

- |

|

SRMR |

.054 |

≤.080 |

|

d_ULS |

1.031 |

>.05 |

|

d_G |

.852 |

>.05 |

|

NFI |

.851 |

≥.80 |

|

GoF |

.536 |

≥.36 |

X2 was calculated as 2320,000 in the research model. SRMR was .054 and lower than the acceptable value of .080 (Hu & Bentler, 1999). NFI was calculated as .851 and was higher than the critical value of .800 (Bentler & Bonet, 1980). It was calculated as d_ULS= 1.031 and d_G= .852, and the exact fit criteria were determined as higher (>.05) than the original values (Dijkstra & Henseler, 2015). GoF was calculated and was higher than .36 (.536) (Tenenhaus et al., 2005). When the AVE were calculated, the values of the scales were in the range of .770 - .897. The values in this range show that the scale items have convergent validity and are accepted because the scores are higher than .50 (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). Therefore, Fornell Larcker criterion was examined to determine the discriminant validity of the scales.

Table 4: Discriminant Validity

EArcheo= Extra Archeological Attraction, DArcheo= Archeotourism development of the destination, LA= Leisure activities, Int= Intention to participate to archeotourism

The scales’ correlation loadings and the AVE’s square root were compared. The mean square root of the variance explained for each scale was higher than the correlation loadings with the others (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). When HTMT scores were examined, it was found to be below .9 (Henseler et al., 2015). The discriminant validity of the scales was evaluated thirdly by comparing the cross loading values.

Table 5: Cross Loadings

EArcheo= Extra Archeological Attraction, DArcheo= Archeotourism development of the destination, LA= Leisure activities, Int= Intention to participate to archeotourism

Correlation loadings between items of each scale were higher than the correlation values with the others (Hair et al., 2019). In this context, the scales provided the discriminant validity requirement. First, the validity and reliability analysis of core archeological attraction, participatory archeological activities, and historic-cultural knowledge scales were calculated differently from the reflective scales due to their formative structure. As a result of the analysis, the external linearity (Outer VIF) results of the scales were lower than 5.0, In this context, formative scales do not have a multicollinearity problem (Mason & Perreault, 1991). Secondly, the statistical significance of the scale items was evaluated in the study.

Table 6: Formative Measures Scores

CArcheo= Core archeological attraction, PArcheo= Participatory archeological activities, HCK= Historic-cultural knowledge

As a result of the analysis, full scale items were significant. In this context, the suitability levels of the scale items for the formative scales were calculated by examining the outer loadings and weights. First, the outer weights of the scales with a formative structure were discussed. Outer weights of HCK3 and PArcheo2 items are over .50, Outer weights of other items are below .50, In this case, the outer loadings of the related items were examined. All items have outer loadings above .50, As a result, although the outer weights do not give the desired effect, the fact that the outer loadings have acceptable values and that each item is statistically significant has proven the validity of the scales.

Structural Model Assessment

We calculated InnerVIF values to examine the connection level according to the scales’ correlation scores. Since the scales are below 1.00 (Smith et al., 2020; Ghozali, 2015), there is no multicollinearity problem. Secondly, the scales’ determination coefficient (R2) was calculated. For the core archeological attractions, the rate of explaining intention to participate in archeotourism was calculated as .84. Since this ratio was above .75, it was evaluated as very good (Henseler et al., 2009). Third, the effect size ( f2 ) of the independent variables on the dependent variable was calculated in the structural model assessment.

Table 7: Structural Model Assessment

|

Measures |

f2 |

InnerVIF |

|---|---|---|

|

ATNyt |

ATNyt | |

|

LA |

0,033 |

3,864 |

|

DArcheo |

0,109 |

5,065 |

|

EArcheo |

0,000 |

1,799 |

|

PArcheo |

0,000 |

1,771 |

|

HCK |

0,113 |

4,200 |

|

CArcheo |

0,088 |

3,194 |

CArcheo= Core archeological attraction, EArcheo= Extra Archeological Attraction, PArcheo= Participatory archeological activities, HCK= Historic-cultural knowledge, DArcheo= Archeotourism development of the destination, LA= Leisure activities, Int= Intention to participate to archeotourism

The effect size of archeotourism development of the destination, historic-cultural knowledge and core archeological attraction scales on the intention to participate in archeotourism was found to be sufficient (Chin, 1998). While the effect level on leisure activities intention to participate in archeotourism was small, extra archeological attraction and participatory archeological activities scales had no effect. In the structural model evaluation process, the estimation error level of the analysis method was calculated based on the research model results.

Table 8: PLSpredict Analysis

When the results of the PLSpredict analysis were examined, the LM_MAE values of the items of intention to participate in archeotourism were higher than the PLS-SEM_MAE values. In addition, the general MAE value of the Int scale was calculated

as .337, the RMSE value as .439, and the Q2 as .809. As a result of all these evaluations, the predictive power of the research

model was high.

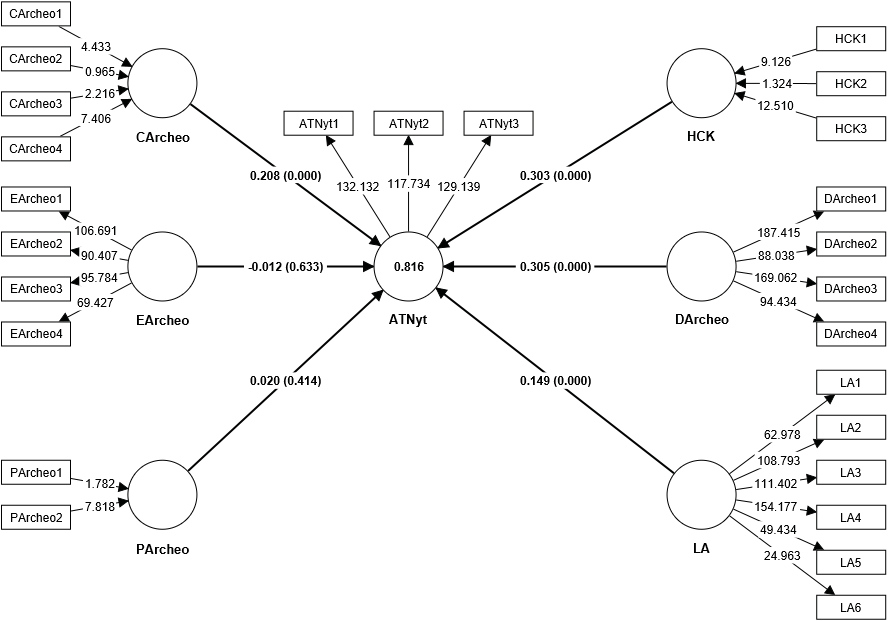

Structural Equation Model Results

As a result of the structural equation model analysis, the core Archeological attractions (ßCArcheo>>Int= .208, t= 3.839, p< .001), historic-cultural knowledge (ßHCK>>Int=.303, t= 9.112, p< .001), archeotourism development of the destination (ßDarcheo>>Int= .305, t= 5.763, p< .001) and leisure activities (ßLA>>Int= .149, t= 3.840, p< .001) has a significant positive effect on the intention to participate to archeotourism. Thus, hypotheses H1a, H1d, H1e and H1f were supported.

Table 9: Structural Equation Model Results

p=< .001***, p=< .01**, p=< .05*

CArcheo= Core archeological attraction, EArcheo= Extra Archeological Attraction, PArcheo= Participatory archeological activities, HCK= Historic-cultural knowledge, DArcheo= Archeotourism development of the destination, LA= Leisure activities, Int= Intention to participate to archeotourism

Extra Archeological attractions ( ßEArcheo>>Int= -.012, t= 0.478, p< .05) and participatory archeological activities ( ßKArcheo>>Int= .020, t= 0.816, p< .05) weren’t positive and significant impact on the intention to participate to archeotourism. As a result, hypotheses H1b and H1c were not supported.

Figure 2: Structural equation model analysis

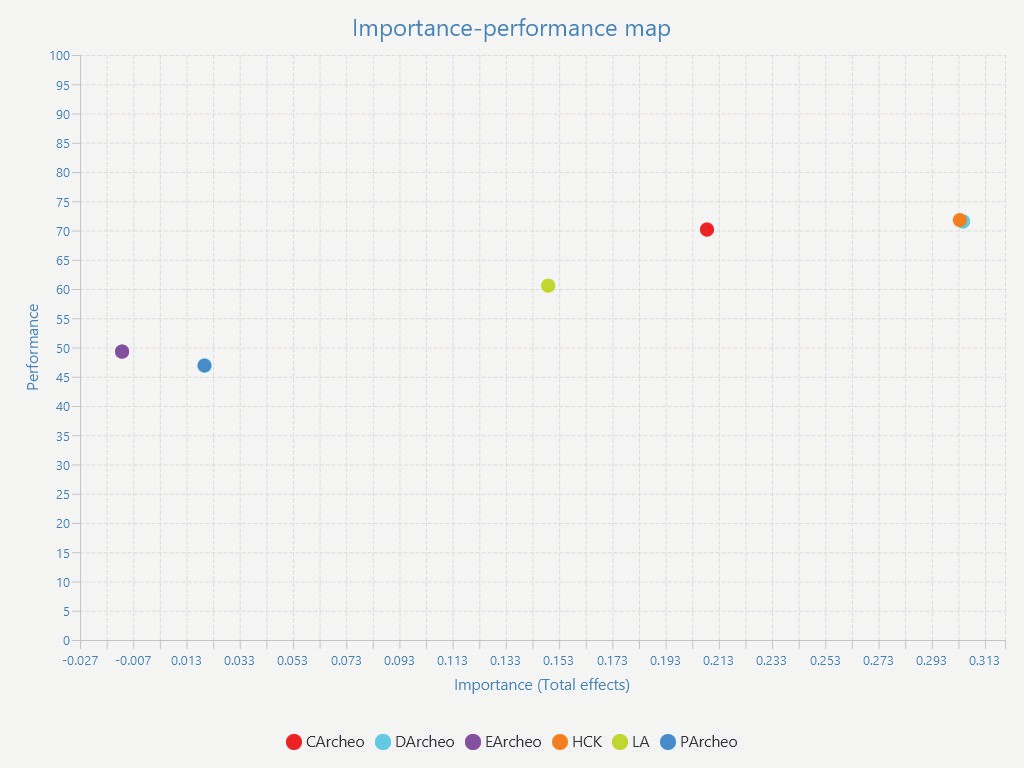

In the research model, importance-performance matrix analysis (IPMA) of dependent variables was performed on intention to participate to archeotourism. IPMA is a grid analysis that explains the overall “significance” effects of the PLS-SEM estimation together with the average “performance” score (Groβ, 2018; Rigdon et al., 2011).

Figure 3: Importance Performance Map

Accordingly, historic-cultural knowledge and participatory archeological activities variables have high importance and performance for Intention to participate to archeotourism. In addition, the importance-performance value of leisure activities is close to 50%. However, although the performance level is high in other independent variables, the significance level is low. Therefore, to increase visits to the destination in the context of archeotourism, local governments and sector representatives are recommended to give importance to ensuring/developing tourists’ participation in activities, participating in activities in their spare time, and presenting historical-cultural information more effectively.

DISCUSSION

We examined the effect of archeotourism motivation factors on the intention to participate in archeotourism in Çorum. Some hypothesis was proposed and analysed. Archeotourism motivation items are composed of six sub-factors. Core archeological attractions, historic-cultural knowledge, and archeotourism development of the destination positively affect intention to participate in archeotourism; however, extra Archeological attractions, participatory Archeological activities, and leisure activities aren’t seen as the chief reason to visit Çorum. Previous literature proves that the destination’s core Archeological attraction, historic-cultural knowledge, and archeotourism development and recreational activities positively affect the intention to participate (Çetinsöz & Artuğer, 2014; Som et al., 2012). Even though There is a limited paper on the effect of extra Archeological attractions, participatory Archeological activities, and leisure activities on destination visitation for archeotourism, Chang (2013) expressed that similar attractiveness doesn’t affect tourist destination choices. Core Archeological attractions are evaluated as ruins, temples, castles, caves, rock tombs, Seljuk, and Ottoman period structures Çorum museums were the most crucial elements for the tourists and had many museums covering the works of antiquity. According to the results, H1a is supported. This results explain that the core Archeological attractions are essential for tourists visiting Çorum for archeotourism purposes. Therefore, the fundamental archeological values of the prehistoric period are influential in developing the tourism sector for Çorum. Similarly, Lwoga and Mwankunda (2020) state that visitors to archeotourism’ destinations care about researching and examining the main Archeological attractions. Erdoğan (2021) expresses that supporting the development of archeotourism’ in destinations with Archeological attractions will also feed the local economy and culture. Parallel to this, implementation and action plans should be created to encourage development due to the high importance of the main archeological attractions for tourists.

Extra Archeological attractions include animated events in Çorum, festivals, concerts held in Archeological sites, virtual tours of historical sites, and restaurants with historical menus. According to the results, H1b is supported. The results shows that extra Archeological attractions didn’t affect the visit intention to Çorum. We proposed some suggestions Since virtual tours attracted significant interest from people, especially during the Covid-19 period (Pourmoradian et al., 2021). However, it is optional for all tourists; sightseeing tours are crucial in visiting archeotourism’ destinations. The ineffectiveness of extra Archeological

attractions for Çorum, one of the most preferred destinations in Turkey, is a significant result for the future of tourism. Because although such technology-based activity areas are notable for consumers (Lekgau et al., 2021; Cheney & Hatch, 2020; Guerra et al., 2015), there are still issues such as insufficient space, malfunctioning, or inability to use equipment in Çorum, according to interviews with Çorum museum. This issue can be seen as the inadequacy of the museum management. Because when tourists visit the destination, the lack of access to technology-based facilities causes them to be dissatisfied with the service. Participatory archeological activities include accommodation and application in the Çorum Museum, cooking activities of Hittite dishes, representative excavations, clay, product production, etc. The Çorum Museum has the infrastructure and various opportunities for such activities. According to the results, H1c is supported. The results explain that the tourists could not reach such activities during their visits, and Participatory archeological activities weren’t the main reason for destination choice. According to Mickleburgh et al. (2020) ; experiences such as digital burial rituals are essential for touristic development. Finally, Aydin and Ozkaya (2022) express the importance of the Hittite cuisine for the development of archeotourism’ in the region, with their study revealing the relationship between Hittite cuisine and Anatolian cuisine. After the field research, these areas were determined to use an appointment system. Therefore, these facilities are not in use enough for tourists coming to the destination approximately. Also, the relevant areas were not open for use in August 2022. In addition, very few restaurants in the region prepare products for the Hittite cuisine (Kement & Başar, 2016). Therefore, inadequate service of the area in this context can be shown as a factor in the effect of participating in Archeological attractions on participation intention.

According to results, H1d is supported. The results Show that Historic-cultural knowledge is an influential factor in tourist visitation in Çorum. This result is a common situation regarding the destination’s many historical and cultural values. The knowledge presented in the historical areas and museums are sufficient and reasonable. The destination provides the necessary infrastructure service. The result of the research is similar to Dans and González (2019)’research, which expresses the intensity of tourism mobility for historical and cultural information purposes in their studies. In parallel with this result, Kherrour, Hattab, and Rezzaz (2020) also state that cultural tourism has an esssential share in archeotourism’ in their studies. Corum has created the necessary infrastructure service in terms of historical-cultural information. In addition, tourists see the destination as developed or developing in terms of archeotourism. According to the results, H1e is supported. The results prove that Archeotourism Development of the Destination affects the visit intentions. Mulyantari et al. (2021) state that the importance of Archeological development for cultural tourism activities is high. The result proves this assumption. Furthermore, archeotourism’ is a crucial element in the development of modern societies (Li & Qian, 2017). Current excavations, artifacts in museums, protected ruins, and visitor centers represent the development of the destination. Leisure activities positively affect the intention to participate in archeotourism. As a result of this result, H1f is supported. This means that Çorum is an archeotourism’ destination, entertainment, and sufficient to serve hedonic motives. Furthermore, the statement of Johnson (2011), “archaeology has traditionally had a powerful association with leisure activity,” confirms this conclusion. Therefore, archeotourism’ will be able to improve its tourist attraction if it is enriched with leisure activities (Martínez-Hernández et al, 2021; Díaz-Andreu, 2020).

Practical Implementations

This study has some important practical implications to ensure the tourism development of Çorum archeotourism’. The destination has a significant history in archeotourism’ (Günay, 2007) and an important position in world history (UNESCO, 2022). In terms of being the center of the Hittite Civilization, Çorum offers a high level of historical and cultural information thanks to its ruins. According to results, destination attracts tourists because it provides rich heritage. The desire of people to concentrate on different types of tourism has made historical and cultural tourism activities gain importance since the 2000s. Therefore, to increase the participation of local administrators and residents in archeotourism’ activities in the destination, it is necessary to highlight the historical and cultural information. The results of this research emphasize the need to focus on historical and cultural knowledge to improve the tourist visit to the destination. As a result of the examinations made in Çorum, the suggestions that will contribute to organizational and social development are given below;

Integrating the monumental buildings in Çorum with the newly released works will contribute to cultural unity and sustainability.

In the restoration of Archeological sites, integrity should be ensured in the design, and the original state of the city image should be preserved. Also, Necessary protection measures should be taken to prevent further destruction of architectural structures due to natural and human factors.

Yazılıkaya open-air worship center is affected by climatic conditions. Over time, erosion has occurred in the reliefs made on the rock surfaces. The area can be protected from the effects of sun rays, rain, and snow, by covering it with a roof system. Also, some surfaces have cracks. These cracks prepare the ground for plant roots, moss, and lichen layer formation. Therefore, conservation practices should be made on all surfaces and periodically.

Hattusha could not contribute to the physical structuring of today’s Boğazköy district Despite its long existence as the capital and religious center of the Hittite empire. It is impossible to see the street systems and monumental structures that crossed each other 90º thousands of years ago in the district center. Modern-built houses with several floors are not suitable for the city’s silhouette. Existing buildings in the district can be transformed entirely into a Hittite village

by considering the change of facades and the structures of Hattusha.

Since the “Hittite Village Project” building, supported by the Central Black Sea Development Agency, is not actively used and the necessary repairs are not made, spills are observed on the facade of the building. The existing building can be actively used by completing the required repairs.

Alacahöyük, a religious center and one of the critical residential areas, is the most-visited center for visitors who want to get to know the Hittite civilization. Since it is located in a small center, it is difficult to spend a long time, and no businesses can meet the expectation. A reception area can be created to meet the visitor’s needs at the entrance.

Board Training is given in Çorum Museum. In addition to project-oriented training such as the “Everyone to the Museum” project, continuous activities should be provided for the protection and sustainability of cultural heritage.

Çorum Archeology Museum has integrated exhibition methods and technological innovation. According to the interview, the “Chariot Simulator,” burial traditions and Hittite vases interactive application, touch screens, and voice guidance systems providing information about the artifacts have been broken for a long time. Tools and techniques should be activated to increase the knowledge and satisfaction of the visitors.

There is extensive information about Hittite cuisine through written tablets. However, local businesses need to be aware of the Hittite cuisine. Serving Hittite cuisine in regional restaurants will contribute to gastronomic tourism.

Firstly, public awareness should be raised for permanent solutions. Revealing the tourism potential in the district contributes to cultural heritage protection. Local participation positively affects tourism developments and activities. Therefore, projects need to inform the local people about the Hittite heritage in their region and encourage them to take a more active role in tourism. The conservation and use approach is widespread in cultural heritage protection. In this context, it should be aimed at protecting cultural heritage through tourism activities and contributing to the local economy. Excavations have been carried out in ancient cities in Çorum for a long time, and it is possible to have information about the city plan and settlement thanks to the unearthed structures. However, there is no necessary promotion and information about ancient cities in the Çorum center and districts. Information boards are usually located in front of the relevant museum or building. Artifacts showing the richness of the town and the Hittite civilization are exhibited in the museums located just inside the ruins or in the district where the ancient city is located. Especially the recreation and simulation applications in Çorum museum offer different experiences. The project- oriented training in the museum appeals to groups of all ages and aims to raise awareness of the protection of cultural heritage. Çorum Governorship has made promotional booklets available from museums to promote the city and the Hittite civilization. In addition, the Hittitology congresses held at certain intervals bring together foreign and local scientists scientifically.

The aspects of the city of Çorum that support historical-cultural information, such as Archeological sites, historical and religious centers, and museums, are directly proportional to Turkey’s development level. However, there are not many positive aspects to support this information in terms of cultural tourism, which gives different experiences to the participants. As in European museums, a visual presentation that serves other senses and the opportunity to experience an ingredient or taste like in ancient times does not exist in Turkey yet. Çorum is insufficient in terms of cultural tourism resources such as special interest trips, art galleries, and traditional food and beverages

Theorical Implementations

Research results offer some theoretical implications. First, essential factors for tourists are the presentation of historical and cultural information for archeotourism’ destinations (Li & Qian, 2017) and primary archeotourism attractions. Secondly, the development level of the archeotourism’ destinations and leisure activities are also essential factors for tourists to visit the relevant destination. Because tourists need destination development to meet their basic needs and participate in extra activities during their visit, therefore, tourists may have expectations for preserving historical values in archeotourism’ destinations. For example, Tourists expect extra or participatory archeotourism attractions such as serving Hittite cuisine in Çorum (Kement & Başar, 2016), reviving Archeological excavations (Mickleburgh et al., 2020), realizing virtual tours (Pourmoradian et al, 2021). The fact that the extra archeotourism attractions do not affect the intention to participate is that the extra archeotourism attractions are insufficient in the destination. This research enables the determination of the visit intention to Çorum destination within the scope of archeotourism’. The study tries to bridge the gap between tourists’ choices and their visits. We used the structural equation model and a performance-importance map. We determined what local governments and tourism businesses should pay attention to for more tourists.

CONCLUSION

We examined the significance of the attractive motivation factors of archeotourism to determine intention to visit in Çorum. Archeotourism incentives composed of different sub-factors. Archeotourism activities such as core archeotourism’, extra archeotourism, and participatory archeotourism were selected, and their effect on intention to visit was examined. We determined the level of destination development, leisure activities, and the impact of the historic-cultural information offered by the destination on the intention to participate in archeology. According to results; the historic- cultural knowledge has

emerged as the most important factor for tourists to visit for archeotourism’ purposes. The main archeotourism attractions as archeotourism development of the destination, leisure activities followed this factor. Finally, the primary reason on visit intention to Çorum are historic-cultural knowledge, core archeotourism’ attractions, and archeotourism development of the destination Extra archeological attraction and participatory archeological activities didn’t affect the visit intention to Çorum since the absence or insufficiency of extra and participatory archeological activities.

Limitations and Future Research

We conducted the research only in Çorum destination and examined visit intention through the attractive motivation factors of archeotourism. Data were collected during the summer period. Therefore, other datas collected in other periods were excluded from the study. In the future study, motivational factors can be evaluated in two categories: push and pull. In addition, tourists’ visit intentions can be assessed on issues such as the perceived value of archeotourism activities and their views on the service offered at the destination. In addition, information can be gathered from residents and stakeholders’ opinion on destination development and future insights. A model proposal was presented and evaluated with a quantitative research design. In future studies, the archeotourism evaluation of the destination can be made using a combination of qualitative and quantitative research design. It is thought that the results of this research will shed light on the administrative review of the destination in the context of archeotourism. Therefore, it can be said that the results will also serve as a guide for future studies.