INTRODUCTION

In the twenty-first century, the concept of a successful career has evolved. Modern-day workers aspire to be perpetual learners with a strong focus on autonomous career management. Consequently, careers are becoming more “boundaryless” and “protean,” characterized by increased self-directedness and personal career achievement as significant life goals (Rigotti et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2015). Research has demonstrated that adopting a protean and boundaryless career approach is associated with favourable work-related results like work enthusiasm, organizational dedication, and job contentment (Gulyani & Bhatnagar, 2017; Redondo et al., 2021). Nevertheless, there has been relatively limited focus on comprehending the consequences of this approach on an individual’s career-related outcomes (Kundi et al., 2022a; Kundi et al., 2022b; Wiernik & Kostal, 2019).

The COVID-19 pandemic has further blurred the lines between work and personal life, challenging our understanding of a successful career (Carnevale & Hatak, 2020; Hamzah et al., 2022; Su et al., 2022). While some studies on career success have primarily focused on objectified work-related dimensions like hierarchical status, advancement, and income levels (Abele & Spurk, 2009; Rigotti et al., 2020; Shockley et al., 2016; Spurk et al., 2019), few have expanded their scope to include subjective aspects such as moral satisfaction, aligning one’s values and actively engaging with social recognition (Pan & Zhou, 2015; Rigotti et al., 2020; Schultheiss et al., 2023). With evolving job market conditions, the concept of a successful career is now closely associated with pursuing personal aspirations and achieving self-fulfillment, diverging from the traditional notion of adhering to predetermined organizational career paths (Gaile et al., 2022),

Furthermore, existing research has predominantly focused on organizational success metrics, leaving individual employee success relatively unexplored (Walker, 2021). Research has mostly emphasized objective and monetary measures within the domain of individual success metrics, neglecting its subjective dimensions (Carstens et al., 2021). This study aims to fulfill this gap by primarily looking into individual-level career success, assessing one’s career path through personalized, subjective aspects crucial to the individual, known as subjective career success (SCS) (Rigotti et al., 2020; Schultheiss et al., 2023; Steindórsdóttir et al., 2023). CC assumes particular significance in this context, as contemporary workers value career advancement and enriching their professional journeys (Gaile et al., 2022). In this context, CC refers to “an individual’s intent to remain in a specific occupation and their determination to acquire the necessary skills for success” (Ekmekcioglu et al., 2020; Gebbels et al., 2020).

Researchers highlight that it is crucial to consider individual factors beyond commitment when examining career success. Various researchers have called for investigations into individual factors as potential intervening variables (Mishra & McDonald, 2017; Najam et al., 2020), including emotional intelligence, career aspirations, self-efficacy, job complexity, and work-life balance, potentially altering its strength and direction (Ekmekcioglu et al., 2020; Sultana et al., 2016). Self-efficacy (SE) has gained attention in career studies (Ballout, 2009; Hamzah et al., 2022; Rigotti et al., 2020). High SE, as described by Schultheiss et al. (2023), drives goal-directed behavior and encourages individuals with high SE to set challenging goals due to their strong belief in their ability to achieve these objectives (Ahmed, 2019; Ballout, 2009; Spurk et al., 2019). Career-related SE behaviors significantly influence various individual and organizational aspects, including career goals, learning, achievements, and workplace effectiveness (Liu, 2019; Rigotti et al., 2020). In this study, we explore how SE predicts SCS alongside CC. Specifically, we focus on career-related SE, an individual’s conviction to navigate a successful career path.

Furthermore, the ability to rebound effectively from challenges and setbacks referred to as resilience, has gained significant prominence (Jiang et al., 2019; Morrison & Buhalis, 2024; Su et al., 2022). This emphasis on resilience is particularly relevant in light of the disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, introducing social and political uncertainties (Hite & McDonald, 2020; Rudolph & Zacher, 2020). Mishra and McDonald (2017) have proposed the concept of career resilience (CR) as a potential intervening variable in the connection between CC and SCS. Studies highlight resilience as a significant factor influencing perceptions of career success (Ahmad et al., 2019; Gu, 2014; Schultheiss et al., 2023; Wei & Taormina, 2014). Despite the exploration of individual components, a comprehensive investigation into their sequential interplay remains to be limited. Additionally, the career management literature has primarily overlooked the employees from the tourism industry (Meira et al., 2023), especially in developing nations like India (Park & Kang, 2019). The Indian tourism industry is pivotal in driving economic growth, contributing 33.82% to the Asia-Pacific region India Tourist Statistic (Ministry of Tourism, 2022). Examining this industry and its human resources ensures its long-term sustainability. Seasonality, low wages, unfavourable working hours, and employment insecurity have contributed to employee disengagement and turnover rates within the tourism sector (Bhawna et al., 2023; Su et al., 2022). These issues significantly impact employees’ CC, relative success, and intention to remain in the industry.

This study primarily explores serial mediation, focusing on how CC sets a chain of influence in motion. It starts with CC, which then promotes SE, subsequently influencing the development of CR, ultimately resulting in SCS. This research offers multifaceted contributions, shedding light on the underlying mechanisms through which these constructs collectively shape career paths. Moreover, situating the study within the Indian tourism industry holds strategic relevance due to the sector’s economic significance and timely relevance amid challenges related to turnover and engagement. The study’s implications extend to talent retention, a critical concern in the tourism industry with high turnover rates, seasonality, and wage issues. Understanding how employees’ CC and SCS relate to their intention to stay in the industry can reduce business recruitment and training costs.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK AND LITERATURE REVIEW

This study is anchored in two robust theories of career development: the Career Self-Determination Theory (CSDT) and the Contextual Action Theory of Career Development (CATCD). The deliberate inclusion of these theories is driven by the pressing need for a comprehensive grasp of the intricate facets surrounding the concept of career success. Chen (2017) pioneered the application of Self-Determination Theory (SDT) to the realm of careers and vocations, giving rise to CSDT. According to this theory, individuals are most likely to attain career satisfaction and success when they experience a sense of autonomy, competence, and relatedness. In the context of CSDT, CC can be interpreted as a manifestation of an individual’s self-driven motivation toward their career goals. Committing to their careers signifies a deep alignment with their chosen career paths and an intrinsic drive to pursue them (Ballout, 2009; Poon, 2004) . High SE contributes to a sense of competence, which aligns with the principles of autonomy and competence within CSDT. SCS is viewed as the outcome of autonomous motivation, SE, and CR (Pasha et al., 2017). According to CSDT, individuals who possess intrinsic motivation, high SE, and resilience in their career pursuits are more likely to achieve SCS.

On the other hand, the CATCD framework posits that the level of CC and success is heavily influenced by the alignment between personal goals and available opportunities (Valach & Young, 2002). This theory underscores that individuals deeply committed to their careers tend to engage in activities that harmonize with their aspirations and can adeptly identify relevant opportunities on their professional journey (Pan & Zhou, 2015). SCS is the culmination of the interplay between an individual’s actions and career context. CATCD highlights how an individual’s career choices and actions are profoundly shaped by the surrounding context, which, in turn, affects their SCS. Consequently, those who cultivate a profound CC, establish well-defined goals and recognize the diverse pathways available significantly enhance their potential for success in their chosen field. By seamlessly integrating CSDT and CATCD, this study forges a comprehensive theoretical framework. CSDT elucidates how intrinsic motivation and competence shape CC, while CATCD sheds light on the intricate relationship between personal goals, commitment, and the recognition of pertinent opportunities. This fusion lays a sturdy foundation for comprehending the complex dynamics of career success and commitment within the distinctive context of India’s tourism industry.

CC and SCS

In line with modern management concepts, contemporary success is no longer solely tethered to organizational achievements but is intricately tied to employees’ capacity to fulfill their objectives. CC is a testament to an individual’s unwavering dedication to their career, deeply intertwined with their aspirations (Ballout, 2009).

Within this evolving landscape, career success takes on a multifaceted character characterized by attaining personal and professional goals within one’s chosen vocation. This concept is highly subjective, varying from person to person, shaped by personal values, objectives, resilience, commitment, and more (Pan & Zhou, 2015). The literature delineates career success along two distinct perspectives: objective and subjective. Objective career success is often gauged by tangible markers such as improved compensation, promotions, or external recognition (Biemann & Braakmann, 2013; Spurk et al., 2019). In contrast, SCS draws from internal factors, encompassing self-development, recognition, influence, authenticity, meaningful work, self- fulfillment, and the extent to which individuals can actualize their occupational aspirations (Abele & Spurk, 2009;, Soomro et al., 2022; Rigotti et al., 2020). Individuals pursuing protean careers prioritize subjective career goals and strive for subjective success (Park & Rothwell, 2009; Pathardikar et al., 2016). The contemporary research landscape increasingly emphasizes SCS as the primary metric of career success, eclipsing traditional objective measures like salary or job title, driven by the evolving dynamics of cross-organizational mobility and changing career paradigms (Ekmekcioglu et al., 2020; Gaile et al., 2022).

Drawing from the CSDT, it becomes apparent that individuals are likelier to exhibit strong CC when they experience fulfillment and satisfaction in their work (Chen, 2017). According to this theory, those with a strong commitment to their careers tend to invest more time, effort, and energy into their job, consequently elevating their SCS (Kim & Beehr, 2017; Pasha et al., 2017; Pathardikar et al., 2016). In theory, it is widely acknowledged that heightened dedication to one’s work positively correlates with higher SCS (Ekmekcioglu et al., 2020; Pan & Zhou, 2015; Schultheiss et al., 2023). However, given the tourism industry’s highly dynamic and fiercely competitive nature (Meira et al., 2023), factors that may influence individuals’ CC and subsequent SCS warrant exploration within this unique context (Baum, 2015; Richardson, 2009). While it might seem intuitive that CC bolsters SCS, empirical evidence within the tourism sector remains limited (Lee & Chen, 2013; Wang, 2016).

Furthermore, previous research underscores the pivotal role of CC within the tourism sector, as it nurtures employees’ unwavering commitment to their roles, ultimately enhancing the quality of guest experiences (Koyuncu et al., 2008; Su et al., 2022; Wang, 2016). The distinctive nature of the tourism industry, where employees’ enthusiasm and passion for travel, cultures, and hospitality are paramount, underscores the practical significance of understanding the relationship between CC and job performance (Shabbir et al., 2017; Wang, 2016). Given the industry’s customer-centric nature, a profound link exists between employees’ CC and their ability to provide exceptional service and create memorable travel experiences. This underscores the practical importance of comprehending this relationship. Moreover, the tourism sector’s dynamic and seasonal nature presents specific challenges. CC has been shown to bolster employees’ resilience in the face of these fluctuations, thus contributing to talent retention and the industry’s long-term sustainability (Su et al., 2022). SCS, another focal point of this study, goes beyond traditional career advancement metrics, encapsulating employees’ well-being, job satisfaction, and the fulfillment they derive from their roles in the tourism sector, aligning with broader trends in well-being research. Therefore, we put forth the hypothesis that:

H1: There is a positive relationship between CC and SCS.

CC, SE and SCS

SE, a foundational psychological concept, revolves around an individual’s unwavering belief in their capacity to complete tasks and achieve their desired objectives triumphantly (King et al., 2010). It hinges on an individual’s perception of competence and confidence, underscoring their unwavering belief in possessing the requisite skills, knowledge, and resources to excel in a specific domain. SE represents a critical positive self-assessment and has garnered extensive attention as a pivotal determinant of goal-oriented behaviour. Its applicability spans diverse fields, from general SE influencing various aspects of life to more specialized (Al-mehsin, 2017; King et al., 2010) and adaptable forms like occupational SE (Liu, 2019; Rigotti et al., 2020) and task-specific SE (Guillén, 2021).

In our pursuit of understanding SE as a predictor of SCS, we spotlight career-related SE, defined as an individual’s conviction in their ability to navigate their career path successfully (Rigotti et al., 2020). While some empirical evidence suggests that SE plays a pivotal role in shaping career choices and eventual career success (Ahmed, 2019; Liu, 2019; Schultheiss et al., 2023), the sources of SE have yet to be explored. Previous research examining the relationship between SE and career success and career decisions has employed a range of constructs that may only partially align with our specific research context, focused on middle-aged professionals. Empirical support for a positive feedback loop between occupational SE, SCS, and objective career success (Abele & Spurk, 2009; Djourova et al., 2020; Hamzah et al., 2022). According to the CSDT, individuals with higher levels of CC are more likely to exude a robust sense of SE within their chosen profession (Chen, 2017).

Further research by Vogus and Sutcliffe (2007) underscores that individuals endowed with self-confidence and a proactive mindset are inherently inclined to engage in career self-management activities. Their self-assured disposition and proactive approach empower them to adeptly navigate challenges, adapt to changes, and ultimately triumph in realizing their career aspirations (Gaile et al., 2022). CC is intricately intertwined with an individual’s sense of SE, culminating in an amplified sense of fulfillment and, ultimately, SCS. Employees with a strong commitment to their careers are more prone to fashion strategies that align harmoniously with their career goals and employers’ objectives. In this context, SE is an enabler, enhancing performance and reinforcing these career aspirations (Rigotti et al., 2020). In light of the preceding arguments, we thus believe that:

H2: SE will mediate the relationship between CC and SCS.

CC, CR and SCS

The “career resilience” concept introduced by London and Stumpf (1982) underscores an individual’s capacity to confront and rebound from career-related setbacks and interruptions. This resilience, as further characterized by Mishra and McDonald (2017) and Su et al. (2022), represents the unique ability to survive and fully bounce back from severe conditions, setbacks, trauma, and other challenges. It’s worth noting that these resilient qualities have been identified as pivotal for success in leadership roles (Ahmad et al., 2019; Schultheiss et al., 2023). CC can be seen as the initial resource or catalyst in the career development process. Analytically, this resource accumulation acts as a chain reaction, ultimately contributing to improved career success (Park & Kang, 2019; Wei & Taormina, 2014).

According to numerous scholars, resilience can be viewed as a predictor of success. Individuals who exhibit resilience by enduring, adapting, and building strength are likelier to achieve career success (Djourova et al., 2020; Gu, 2014; Richtnér & Löfsten, 2014; Wei & Taormina, 2014). Su et al. (2022) suggest that successful employees can persevere and emerge stronger after facing challenging conditions and adversity. Consequently, resilience plays a pivotal role in helping employees effectively cope with and adapt to workplace challenges in environments characterized by ambiguity, rapid change, and crises, potentially paving the way for career success (Guillén, 2021). Numerous studies provide evidence of how resilience can be considered a personal factor contributing to SCS (Ahmad et al., 2019; Carstens et al., 2021; Ekmekcioglu et al., 2020; Schultheiss et al., 2023). Thus, it can be said that individuals with high CC are more likely to invest in skill development, set ambitious career goals, and exhibit a proactive approach to their profession. This proactive behaviour leads to the development of CR.

However, it’s crucial to recognize that SCS hinges on ongoing learning, adaptability to change, effective career self- management, and the ability to meet evolving market demands (Carstens et al., 2021). Understanding employees’ capacity to acquire and utilize resources to overcome career challenges becomes crucial, especially when confronted with the need to adjust to changing work requirements (Guillén, 2021; Mishra & McDonald, 2017; Richtnér & Löfsten, 2014). According to the CACTD, individuals with a robust sense of CC demonstrate resilient behaviours and attitudes when faced with career-related challenges and maintain a positive outlook in their career pursuits (Richtnér & Löfsten, 2014).

Various studies across different professions and industries, including teaching, dentists, hospitality, IT, administration, etc., have underscored the significance of resilience (Gu, 2014; Park & Kang, 2019; Steindórsdóttir et al., 2023; Su et al., 2022) and its importance in career orientation, performance advantages, indicating that resilience enhances one’s potential to achieve goals. Gu (2014) found a relationship between teachers’ commitment and resilience in teaching. Hasan (2016) concluded that CC and CR form a positive cycle, promoting personal growth, adaptability, and long-term success in individuals’ professional journeys. Furthermore, Park and Kang (2019) discovered that dental hygienists’ commitment significantly increased when they exhibited resilience at work, as evidenced by measures of success such as job satisfaction, enjoyment at work, and commitment. Based on extensive literature, it can be argued that committed and resilient individuals are more likely to succeed in dynamic and challenging work situations. In light of this, we hypothesize:

H3: CR will serve as a mediating factor in the relationship between CC and SCS.

Serial Mediation

The intrinsic essence of SE and resilience share common characteristics, embodying the profound ability to persevere through adversity while retaining their distinctive psychological significance (Sultana et al., 2016). This symbiotic relationship unfolds as individuals who exhibit unwavering commitment to their career pursuits engage in a symphony of activities that amplify their competence and lay the foundation for developing SE beliefs (Hasan, 2016). In this intricate interplay, individuals with higher levels of SE possess an unwavering belief in their capacity to overcome any obstacle that comes their way, shaping a path toward accomplishment (Gaile et al., 2022). This deep-rooted resilience emerges as their secret weapon, endowing them with the power to rebound from setbacks, masterfully adapt to the ever-evolving tides of change, and ingeniously chart alternative pathways to realize their career aspirations (Youssef & Luthans, 2007). This resilience and SE beliefs foster a sense of accomplishment and

contentment in their careers, contributing to their SCS (Park & Kang, 2019). At the foundation of SE, CC fosters an environment that fuels the growth of CR. Here, SE and resilience create a powerful shield, enabling individuals to skilfully navigate challenges, adapt to changes, and persist in their chosen career path (Chen, 2017). This harmonious partnership between resilience and SE leads to SCS, marked by goal attainment, contentment, and personal fulfillment (Luthans and Peterson, 2002). Empirical studies have recognized SE, commitment, and resilience as individual contributors to the captivating narrative of SCS (Hasan, 2016). In this complex interaction, where commitment enhances SE and resilience, it can be hypothesized:

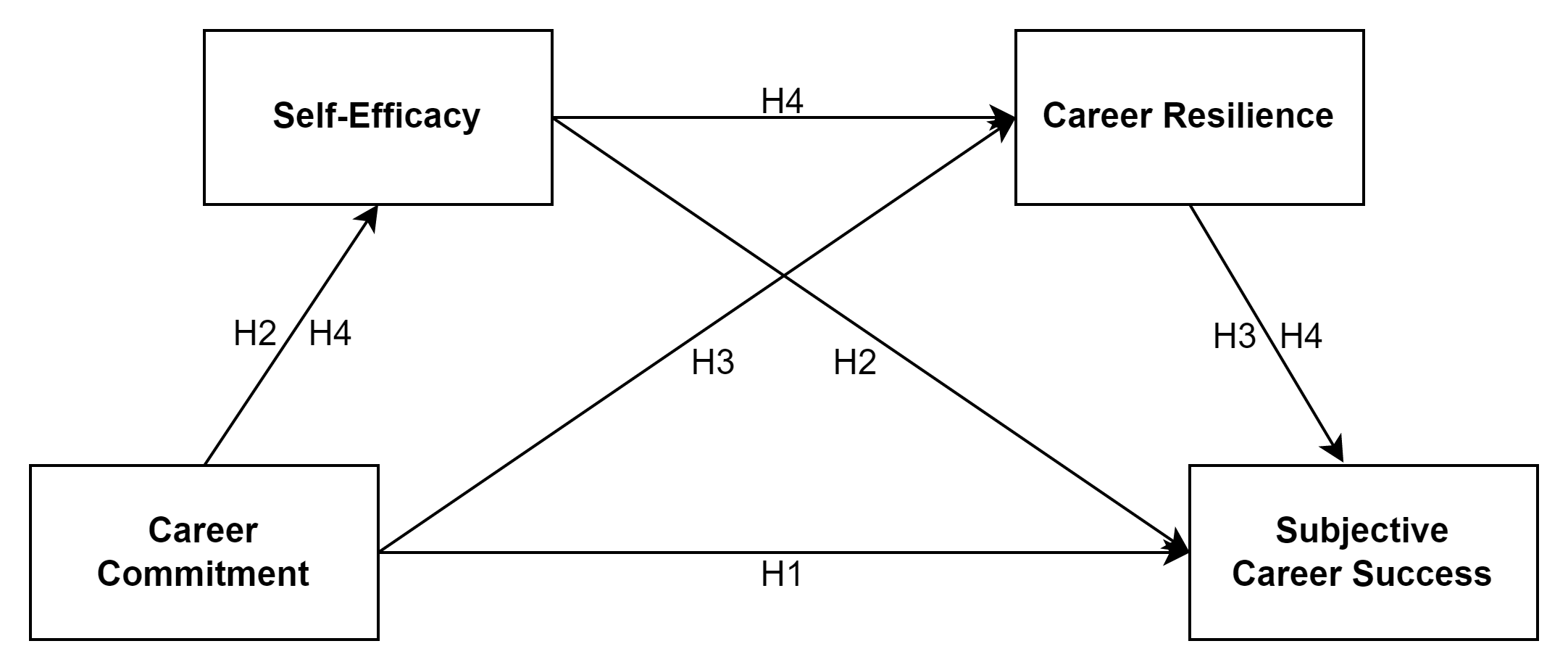

H4: SE and CR serve as serial mediators in the relationship between CC and SCS. Figure 1: Conceptual Model

RESEARCH METHOD

This study employed a two-wave longitudinal design to enhance the analysis accuracy through an online questionnaire. The participants were systematically sampled from tourism workers with at least one year of sector experience, preferably those with more extensive backgrounds. Selection criteria were based on data from the Ministry of Tourism (India), specifically focusing on travel and tour operators in Punjab, a region notable for its substantial foreign tourist visits (29.2% as per India Tourism Statistics in 2022). Data collection involved the use of a Google form, with an emphasis on ensuring participant confidentiality and voluntary participation. The data collection process spanned several months: the first wave, conducted between June and July 2022, gathered demographic information and the predictor variable (CC). Subsequently, after a three-month gap, the second wave, conducted in November and December 2022, focused on the mediators (SE & CR) and the outcome (SCS), adhering to recommendations by Dormann and Griffin (2015). The comprehensive survey instrument covered demographics and critical elements: CC, SE, CR, and SCS. Initially, 438 fully completed questionnaires were collected, with an additional 371 respondents completing the second survey from January to February 2023. Rigorous data cleaning procedures were used, including matching unique response IDs and timestamps between wave-1 and wave-2, and addressing seven statistical outliers using the Cook’s distance method. Prior to analysis, the data underwent a thorough assessment for normality, confirming a normal distribution with no skewness values exceeding three or kurtosis values surpassing 10. After removal of duplicates, invalid values, and missing responses, the final dataset comprised 357 valid responses. For data analysis, SPSS and AMOS 25 software were utilized. Rigorous measures were taken to prevent common method bias (CMB), including assessing collinearity using VIF (Variance Inflation Factor, with scores ranging from 2.6 to 3.1). Principal component analysis and varimax rotation of scale items revealed four EFA factors aligned with the study’s theory, with no dominant general factor emerging, thereby indicating minimal bias (Harman, 1976). The results provided robust evidence that CMB is unlikely to impact the study’s findings.

Measuring instruments

The eight-item scale was adopted from Blau (1985) to measure CC, reflecting participants’ dedication to their chosen profession. Item CC1, CC3, and CC7 were reverse coded. SE was evaluated using an 8-item scale from Chen et al. (2001). This scale reflects the confidence in one’s ability to perform a specific task or achieve in managing one’s career. While performing CFA measurement items with less than 0.5 loadings were excluded (SE6, SE7), leaving us with six items. To measure SCS, a 24-item scale with eight different dimensions— ‘recognition,’‘influence,’‘work quality,’‘meaningful work,’‘authenticity,’‘satisfaction,’ ‘personal life,’ and ‘growth development,’ developed by Shockley et al., (2016), which were coded as “Recognition (SCR1, SCR2, SCR3), Quality work (SCQW1, SCQW2, SCQW3), Meaningful work (SCMW1, SCMW2, SCMW3), Influence (SCI1, SCI2, SCI3), Authenticity (SCA1, SCA2, SCA3), Personal life (SCPL1, SCPL2, SCPL3), Growth & development (SCGD1, SCGD2, SCGD3).” Parameter satisfaction showed loadings lower than 0.5, so we excluded them from the final analysis. A

5-item scale was used to assess CR developed by Stephens, (2013). This indicator evaluates a person’s ability to bounce back from professional obstacles. Additionally, we controlled for demographic variables, including age, gender, educational level, previous managerial tenure, marital status, race, and nationality, as these factors have been frequently linked to career success and other formal aspects (Järlström et al., 2020; Rudolph & Zacher, 2020). All scales were measured on a 5-point Likert scale.

RESULTS

In our study, most respondents were male (60.5%), while females accounted for 44% of participants. Notably, 42.5% fell within the 30-34 age range, and a significant 65.5% held at least a bachelor’s degree, with each participant having at least one year’s experience in the field (table 1). These demographics reflect specific historical and structural dynamics in the tourism industry. Historically, gender roles have influenced the types of jobs men and women were encouraged to pursue, leading to disparities in specific sectors. Additionally, the industry often demands specialized knowledge, explaining the prevalence of bachelor’s degree holders. Specific tourism subsectors, like adventure tourism and outdoor guiding, favour skills traditionally associated with males, leading to their overrepresentation, while career interruptions due to family responsibilities impact women’s progression (Je et al., 2022). Unequal access to education in some regions also contributes to gender disparities. Organizational culture, including work-life balance and diversity policies, influences career choices within the industry. Addressing these dynamics is crucial to promote a more diverse and inclusive workforce.

3.2. Measurement model

Beforehand, we performed a confirmatory factor analysis, i.e., CFA, to assess the validity of the measurement model. The CFA ensured that the measurement variables accurately represented the underlying constructs. Following the CFA, the serial mediation analysis was conducted, estimating the indirect effects through bootstrapping. The measurement model (CC, CR, SE, and SCS) exhibited a favourable fit to the data based on the following indices: CMIN/df = 2.038, CFI = 0.93, AGFI = 0.84, GFI index = 0.95, NFI = 0.92, TLI = 0.85, RMSEA = 0.18, and RMR = 0.03. Furthermore, the validity and reliability of the measurement model were carefully examined. The assessment involved evaluating the factor loadings and the composite reliability values, which exceeded the recommended threshold of 0.70. Additionally, the AVE values surpassed the threshold of

0.50. These findings provide strong evidence for the validity and reliability of the model’s data (Hair et al., 2019).

Table 2: Reliability and validity

Composite

Reliability

AVE MSV

SCPL3 I have been a good employee while maintaining quality non-work relationships.

.742

SCGD1 I have expanded my skill sets to perform better. .659

SCGD2 I have stayed current with changes in my field. .576 SCGD3 I have continuously improved by developing my skill set. .737

CR 0.811 0.505 0.179

CR1 I am getting better at my work because I learn from my mistakes

CR2 Dealing with difficult colleagues (or situations) enables

me to grow

.874

.628

CR3 I see challenges as an opportunity to learn .868

CR4 I find ways to handle unexpected situations .733

CR5 I bounce back when I confront setbacks at work .661

* Reverse coded, Source: Author’s calculation.

Furthermore, discriminant validity was estimated by comparing the average variance extracted (AVE) (Hair et al., 2019). The results indicated that all AVE values exceeded the respective constructs’ MSV values, providing evidence supporting discriminant validity (table 3).

Tables 3: Fornell and Larcker’s discriminant validity criteria

|

Latent Variables |

Max R(H) |

SE |

CC |

SCS |

CR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

SE |

0.964 |

0.729 | |||

|

CC |

0.933 |

0.311*** |

0.811 | ||

|

SCS |

0.936 |

0.562*** |

0.630*** |

0.741 | |

|

CR |

0.949 |

0.301*** |

0.344*** |

0.417*** |

0.712 |

| At **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 | |||||

| 3.3. Descriptive |

Table (4) below displays each variable’s means, standard deviations (SD), and correlation matrix. The responses were evaluated using a 5-point Likert scale, with mean values below 2.4 categorized as low, values between 2.5 and 3.4 considered moderate, and mean values exceeding 3.5 classified as high. The parameters investigated in this study exhibited mean values ranging from

1.56 to 4.71. The primary variables of interest, CC, CR, SE, and SCS, had mean values of 3.71, 3.9, 3.88, and 3.81, respectively.

These findings suggest a high commitment, resilience, SE, and perceived career success among the respondents.

The correlation analysis revealed several noteworthy findings. Firstly, a strong positive correlation (r = 0.844) was found between respondents’ age and years of work experience, indicating a positive relationship between age and professional tenure. The SDs across the constructs ranged from 0.49% to 0.88%, suggesting sufficient variation within the data. CC was found to be significantly and positively correlated with employees’ CR (r = 0.426), SE (r = 0.359), and SCS (r = 0.552). These results indicate that higher levels of CC are associated with greater CR, SE, and SCS. Furthermore, positive and significant associations were found between SE and CR (r = 0.513) and SCS (r = 0.521, r = 0.597). These findings suggest that individuals with higher levels of SE tend to exhibit increased CR and SCS.

Table 4: Descriptive analysis and Correlation metric

|

Variable |

Mean |

SD |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Age |

3.49 |

1.04 |

1 | |||||||

|

Gender |

1.69 |

.502 |

.421** |

1 | ||||||

|

Education |

3.29 |

.773 |

.073 |

-.110 |

1 | |||||

|

Work Experience |

4.73 |

1.41 |

.844** |

-.339** |

.077 |

1 |

The direct effect, represented as H1’ in Table 5, is foundational to exploring the relationship between CC and SCS. This direct effect was significantly positive (β = 0.189, t = 7.66, p < 0.001), indicating that individuals with stronger career commitment tend to perceive greater career success. This aligns with the concept that dedicated individuals are more likely to pursue their goals persistently and overcome challenges.

Using PROCESS model 4, we further examined the roles of SE and CR as mediators (Hayes, 2018). Our analysis revealed a substantial and statistically significant relationship between CC and SE (β = 0.309, t = 8.076, p < 0.01). This suggests that individuals with higher CC levels tend to exhibit greater SE. Career commitment signifies dedication and enhances self-confidence and belief in one’s abilities, aligning with CSDT and the CATCD. Additionally, our analysis unveiled a positive and statistically significant association between CC and CR (β = 0.099, t = 3.304, p < 0.001). This implies that individuals with strong career commitment also tend to demonstrate higher levels of CR, indicating their capacity to adapt and persevere in adversity. This connection arises from the intrinsic motivation and goal-oriented behaviour of dedicated individuals. Furthermore, our observations extended to the significant impact of SE on SCS (β = 0.136, t = 3.70, p < 0.01), revealing that individuals with elevated SE tend to experience heightened SCS. Similarly, CR displayed a notably positive correlation with SCS (β = 0.377, t = 7.99, p < 0.01), indicating that individuals with greater CR are more likely to achieve SCS. These findings shed light on the complex interplay of relationships among career commitment, SE, career resilience, and subjective career success among tourism professionals.

Indirect effects

Partial Mediation by SE (H2 Supported): As demonstrated in Table 5, our analysis revealed the presence of significant indirect effects in the relationship between CC and SCS, mediated by SE. Specifically, the calculated β coefficient was 0.361, with a Boot standard error (BootStd.E) of 0.119, falling within the 95% CI, which explains the strength and direction of the indirect effect of CC on SCS through the mediating role of SE, supporting H2. The interpretation of this finding is that individuals with higher levels of CC may develop greater beliefs in their competence and abilities (SE). This, in turn, leads them to set more ambitious career goals and enhances their confidence in pursuing and achieving these goals. This phenomenon underscores the importance of CC in shaping career aspirations and fostering the self-confidence necessary to attain those aspirations. The BootStd.E provides an estimate of the variability in the indirect effect, and the fact that it falls within the 95% CI suggests that this effect is statistically robust and not likely due to random chance. This result provides empirical evidence that CC influences SCS through increased SE, highlighting the importance of self-belief and confidence in achieving career success among individuals committed to their careers.

Our analysis further revealed that CR also plays a significant mediational role in the relationship between CC and SCS, with an indirect effect of 0.418 at p < 0.001, strongly supporting H3, suggesting that CC contributes to the development of CR, which subsequently has a positive impact on SCS. This reflects that their commitment is a motivational force, driving them to persevere and overcome obstacles, ultimately leading to a heightened perception of career success.

Total effect: Serial mediation

Furthermore, we explored the sequential mediating paths in our study using model 6 to test the hypothesis of serial mediation. Results of PROCESS Macro’s model 6 (table 5) showed an impact of commitment to one’s career on SCS in the presence of serial mediators with beta value = .189, the total indirect effect of CC on SCS through two serial mediators (1) SE and (2) CR accounted for b= .117, making to a significant & positive total effect (β = .309, t = 11.7, p < 0.001). In conclusion, higher CC was linked to higher CR behaviour, favourably related to increased SE. The indirect effect of 0.410 highlights the cumulative impact of these mediators, supporting H4. With R2 = 0.307 and R =.551 (p < 0.001), the serial multiple mediation model significantly explained the variance in the respondents’ SCS. Thus, it signifies the robustness of the model in accounting for career success perceptions. This phenomenon indicates that a significant proportion of the variation in SCS among study participants can be

attributed to the combined influence of CC, SE, and CR.

Table 5: CC’s effect on SCS

DISCUSSION

This study delves into career success, particularly focusing on subjective dimensions, in response to the growing emphasis on individual responsibility for career growth, particularly in tourism. It underscores the robust relationship between CC and SCS (H1), highlighting that individuals with high CC levels are more likely to achieve individual success, aligning with prior research emphasizing the importance of commitment in attaining career outcomes. This finding aligns with previous research highlighting the significance of commitment in achieving career-related results (Ballout, 2009; Ekmekcioglu et al., 2020; Järlström et al., 2020; Koyuncu et al., 2008; Schultheiss et al., 2023; Sultana et al., 2016) but inconsistent with a study by Rigotti et al., (2020) where CC boosted career satisfaction but not SCS. It supports the idea that individuals who actively acquire the essential skills to navigate evolving work environments are likelier to gain the knowledge required for career advancement. The study suggests that professionals with strong CC positively view their career objectives and invest effort in their careers, contributing to SCS.

Additionally, the research delves into the mediating roles of SE and CR (H2 and H3), emphasizing their importance in the relationship between CC and SCS. The findings highlight a significant augmentation in the relationship between CC and SCS among this cohort of tourism employees when they exhibit elevated levels of SE, thereby lending support to Hypothesis 2. This observation implies that when tourism professionals demonstrate robust SE, it amplifies the association between their commitment and their SCS (Salisu et al., 2017). Consequently, even when these professionals do not demonstrate prolonged persistence in their careers, indicative of comparatively lower CC, their SCS can remain elevated if they possess high levels of SE, characterized by a strong belief in their capacity to effectively handle diverse tasks (Abele & Spurk, 2009; Ahmed, 2019; Djourova et al., 2020; Gu, 2014, p. 20; Guillén, 2021; Hasan, 2016; Lee & Chen, 2013; Liu, 2019). In this context, Schultheiss et al. (2023) elaborate that SE plays a pivotal role in shaping the goals individuals set for themselves. Higher SE tends to be associated with adopting more ambitious goals and a stronger commitment to achieving those objectives. This heightened self- assurance in their capabilities to perform tasks successfully subsequently enhances their perception of SCS. SE, in essence, represents an individual’s belief in their capacity to marshal the cognitive resources required to effectively complete a given task (Lee & Chen, 2013). It also influences whether individuals develop a profound interest in their activities, especially when striving for long-term goals like career aspirations (Ahmed, 2019, p. 201). Consequently, employees characterized by high CC and SE are inclined to pursue career goals that offer greater professional advancement and growth opportunities. These proactive behaviours, in turn, lead to heightened productivity and subjective feelings of success (Ballout, 2009; Carstens et al., 2021; Ekmekcioglu et al., 2020; Gaile et al., 2022; Najam et al., 2020).

Regarding the findings concerning CR, our study reveals substantial and positively significant relationships with both CC and SCS. This implies that when individuals in the tourism sector exhibit CR, they are more likely to perceive higher levels of success in their careers. These results align with the proposition put forth by previous studies that CR may function as a trait enabling

tourism professionals to maintain equilibrium in the face of various adverse circumstances within their work environment, ultimately contributing to a more positive perception of their career success (Ahmad et al., 2019; Gu, 2014; Guillén, 2021; Schultheiss et al., 2023; Su et al., 2022). Furthermore, our study demonstrates that CR mediates the relationship between CC and SCS (supporting H3). Additionally, in line with Lyons et al. (2015), we acknowledge that CR may operate differently than general psychological resilience in the career context, as individuals may be unable to shield themselves entirely from the adverse effects of career-related challenges. Therefore, studies investigating CR should adopt a process-oriented perspective to gain deeper insights into its development over time (Mishra & McDonald, 2017; Schultheiss et al., 2023; Su et al., 2022).

Furthermore, our research outcomes support the serial mediation effects of SE and CR in the relationship between CC and SCS, thereby shedding light on the intricate interplay of these critical constructs (H4). These results harmonize seamlessly with prior empirical investigations (Carstens et al., 2021; Schultheiss et al., 2023), amplifying the chorus of evidence that underscores the invaluable role of a resilient mindset and unwavering determination in pursuing professional objectives. From these findings, it becomes evident that CC serves as a catalyst, igniting a sequence of events where individuals with high levels of SE harness their belief in their capabilities to tackle various challenges and tasks effectively. This heightened self-assuredness empowers them to set more ambitious goals and commit to their attainment, further fuelling their CC. Simultaneously, their unwavering CC bolsters their determination to overcome setbacks and adapt to evolving circumstances, enhancing their CR.

CONCLUSION

Tourism professionals work in a fast-changing and demanding environment that requires their full attention and adaptability. Despite the lack of research on the essential attributes for success in this field, our study offers valuable insights into the careers of these professionals. The results underscore the significance of cultivating CC among individuals in casual employment who aspire to achieve a sense of career success and career management. Stronger commitment to professional roles empowers employees to actively shape their careers, gain control, and ultimately attain higher levels of SCS. Understanding these factors is crucial for organizations that maintain a motivated and content workforce while educating professionals on long-term CC. Furthermore, it emphasizes the importance of commitment, perseverance, and adaptability in achieving career success, especially for boundaryless and versatile careerists who rely on SE and resilience.

Recognizing the influential variables shaping employees’ perceptions of professional development is vital for organizations seeking to foster a motivated workforce (Benligiray & Sonmez, 2013). By nurturing these factors, organizations can create an environment that promotes CC and supports individuals in reaching their career goals, ultimately benefiting managers and organizations by providing insights into how commitment and SE influence employees’ perceptions of career success and encouraging the establishment of career advancement opportunities.

5.1 Theoretical implications

Our study makes a substantial theoretical contribution to the tourism industry by enhancing our understanding of the intricate relationship between CC and SCS, supported by the robust theoretical frameworks of CSDT and CATCD, and by investigating the serial mediational roles of SE and CR. The uniqueness of this study lies in several key aspects. Firstly, it delves into the well-established link between CC and SCS, explicitly focusing on tourism professionals. Secondly, it explores the specific CR and SE factors that may influence this relationship. Moreover, given the scarcity of empirical studies addressing the essential qualities for success in the tourism industry, our research sheds light on the levels of CC and SE exhibited by employees in this field.

Through the lens of CSDT, we unravel the motivational factors influencing both CC and SCS, expanding our understanding of the intricate mechanisms through which CC leads to heightened perceptions of career success, especially for individuals pursuing protean and boundaryless careers. We recognize these attributes as potent strategies for achieving coveted career success and delve into how these boundaryless and versatile career attitudes act as catalysts, facilitating employees’ relentless pursuit of career success. The CATCD Theory emphasizes the complex interplay between individuals and their environment, highlighting the impact of support networks, organizational culture, and growth opportunities on career success. Our study not only underscores the salient role of CC in achieving SCS but also emphasizes the need to distinguish it from mere organizational commitment. We illuminate the importance of individuals’ unwavering dedication and active engagement in shaping their unique career paths, transcending the conventional organizational commitment paradigm. Furthermore, our research magnifies the pivotal role of CR in attaining SCS, shedding light on the significance of individuals’ adaptability to change, their ability to rebound from setbacks, and their adept navigation of the myriad challenges encountered on their professional journeys. In sum, our theoretical contributions encompass a multifaceted exploration of these intricate relationships, fostering a deeper understanding of career dynamics in the tourism industry.

5.2. Practical implications

Theimplicationsofthese findings reverberate acrossthetourismindustry. For talentmanagement within the sector, comprehending the intricate relationship between these constructs is indispensable. Organizations can leverage this understanding to devise targeted strategies for cultivating and retaining a motivated and committed workforce. As professionals in the tourism field often grapple with the challenges of a volatile and ever-changing industry, equipping them with the tools to enhance their CC, SE, and resilience becomes essential. Service quality and customer satisfaction within the industry are intimately linked to the motivation and commitment of employees, further emphasizing the practical relevance of our findings. Moreover, in the face of a rapidly evolving global landscape, where the tourism industry is continually reshaped by technological advancements, geopolitical shifts, and changing consumer preferences, a profound comprehension of CC and SCS becomes a compass guiding the sustainability and adaptability of the industry.

In the challenging landscape of the tourism industry, where professionals often grapple with volatility, uncertainty, and complexity, empirical research needs to be more robust in identifying the essential qualities that drive career success. This knowledge gap becomes increasingly significant as organizations face pressing challenges like downsizing, restructuring, and intensified global competition due to technological advancements, reshaping the dynamics of the employment relationship. Protean careers are gaining prominence, where personal development and employability precede traditional notions of job security and advancement within a single organization. Within this evolving employment landscape characterized by flatter organizational structures and reduced job stability, motivating individuals to cultivate a commitment to their careers cannot be overstated. Hence, these findings hold particular significance for both organizations and training institutions. To address this, fostering regular career dialogues with employees about boosting their SE and building CR becomes crucial for their professional growth.

Recognizing CC as a strategic asset surpassing other forms of commitment, such as organizational commitment, becomes imperative. Initiatives like regular career discussions between employees and employers, focusing on enhancing SE and cultivating CR within the context of the tourism profession, are crucial. Career counselling sessions within organizations offer a promising avenue for promoting these qualities among employees, with career counsellors playing a pivotal role in guiding individuals toward evidence-based interventions to bolster SE and resilience in their career paths. This research has significant implications for organizations and training institutions, as it underscores the importance of providing career guidance and optimization strategies to fulfill employees’ developmental needs.

Furthermore, aligning individual values with those of the organization fosters personal career growth in this context. Equipping employees with the skills to adapt, overcome setbacks, and maintain a positive mindset is essential for organizations in the tourism industry. These efforts contribute to the individual career success of employees and the overall success and sustainability of organizations within this sector. Practitioners should deeply understand individual differences, including SE and situational perception, and implement strategies like introspection and training programs to help employees cultivate these attributes. By emphasizing personality development, organizations can actively contribute to the SCS of their employees. Moreover, fostering an organizational culture that values autonomy, efficacy, and well-being significantly enhances CC and career success. Therefore, understanding and nurturing CC is essential for promoting employee engagement and facilitating positive career outcomes in the dynamic tourism industry.

5.3 Limitations and future research directions

This study is subject to several limitations. Firstly, it is essential to note that the study sample was confined to tourism employees, specifically from the Punjab region in India. Consequently, concerns arise regarding the generalizability of the findings to other industries and geographical contexts. To address this, future research should aim to replicate these findings in diverse cultural and geographical settings, utilizing multiple data collection methods to enhance the robustness of the results. Secondly, the analysis examined the role of CC and individual attributes (mainly SE and resilience) in achieving SCS. However, additional factors to consider include organizational culture, support, autonomy levels, growth opportunities, job satisfaction, work-life balance, and social factors such as supportive networks like mentors, colleagues, and family. Future research should address this limitation by incorporating other relevant elements. Thirdly, given the significance of CC and career success for practitioners, it would benefit future researchers to integrate individual factors such as intelligence, personality, and other interacting variables to gain a deeper understanding of the relationship. Overall, these limitations provide opportunities for further exploration.

REFERENCES

An empirical investigation. Asia-Pacific Journal of Business Administration, 11(3), 209–231. https://doi.org/10.1108/APJBA-04-2019-0079

Abdul-Aziz University. International Education Studies, 10(7), 108-117. https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v10n7p108

strategies. International Journal of Manpower, 41(8), 1287–1305. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJM-07-2018-0230

success among Malaysian women managers during the Covid-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Sociology, 7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoc.2022.802090 Harman, H. H. (1976). Modern factor analysis. University of Chicago press.

behaviors. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 24(4), 466–478. https://doi.org/10.1177/1548051817702078

King, D. K., Glasgow, R. E., Toobert, D. J., Strycker, L. A., Estabrooks, P. A., Osuna, D., & Faber, A. J. (2010). Self-efficacy, problem solving, and social-

environmental support are associated with diabetes self-management behaviors. Diabetes Care, 33(4), 751–753. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc09-1746

Statistics%20at%20a%20Glance%20200%20%28Eng%29.pdf

from an Emerging Asian Economy. Administrative Sciences, 10(4). https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci10040082

commitment. Journal of Korean Society of Dental Hygiene, 19(6), 983–992. https://doi.org/10.13065/jksdh.20190084

entrepreneurial career success. International Journal of Economic Research, 14(19), 231-251.

Schultheiss, A. J., Koekemoer, E., & Masenge, A. (2023). Career commitment and subjective career success: Considering the role of career resilience and self-

efficacy. Australian Journal of Career Development, 32(2), 135–146. https://doi.org/10.1177/10384162231172560

year longitudinal study. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2022.103809

The protection motivation theory perspective. Tourism Management Perspectives, 44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2022.101039

subjective career success. Personnel Review, 45(4), 724–742. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-11-2014-0265

Please cite this article as:

for Subjective Career Success. Tourism and Hospitality Management, 30(1), 51-65, https://doi.org/10.20867/thm.30.1.5