Introduction

Understanding collective actions implies understanding citizens’ attitudes toward various political collective actions and intentions to engage in them. Collective actions are defined as actions conducted to improve circumstances for ingroup members and can be roughly divided into normative (conducted in line with the cultural norms of political participation, e.g., peaceful protest) and non-normative (conducted outside the conventional norms of political behaviors or laws, e.g., violent protest) collective actions (Becker & Tausch, 2015; Wright et al., 1990).

The existing literature highlighted many potential determinants of collective actions, which served as a basis for discussions (e.g., the discussion on the role of personality in collective actions; Cawvey et al., 2017) and the development of prominent models like the Social Identity Model of Collective Action (SIMCA; Van Zomeren et al., 2008), or the overarching Model of Belonging, Individual differences, Life experience and Interaction Sustaining Engagement (MOBILISE; Thomas et al., 2022), to name a few. Many models explaining non-normative and violent collective actions also exist (for an overview of processual models, see De Coensel, 2018).

However, according to a recent systematic review of studies addressing the relationship between inequality and political violence (Franc & Pavlović, 2021), most research on political violence is based on a single operationalization of attitudes on collective actions or related attitudes and behaviors. This implies that we know much about the determinants of normative and non-normative collective actions, respectively. However, our knowledge of factors underlying the decision to participate in one form of collective action and not in the other remains limited. This study focuses on the general dark personality trait as one such potential determinant while considering gender differences in collective actions in general.

Dark personality traits and collective actions

Multiple theoretical models explain the role of dark personality traits in collective actions. According to remarks by Cawvey et al. (2017), personality traits should be studied in relation to political behaviors that are conceptually tied to the studied personality traits. Therefore, if we understand the general dark personality trait as the common variance of many variables measuring strong tendencies to achieve personal goals using antisocial means (including neglecting other people’s needs, evoking or abusing their weaknesses; Moshagen et al., 2018), it is not unusual they were first recognized as potential determinants of non-normative collective actions and violent political behavior.

McGregor et al. (2015) provided a theoretical explanation of the relationship between personality traits and (religious) radicalization. The theorists recognized three groups of determinants of violent collective actions, one comprising different personality traits related to sensitivity to provocations or aggression (such as the dark personality traits). In brief, unfavorable circumstances like perceived threats or conflicts may activate a behavioral inhibition system, which leads an organism into an uneasy state. In such a state, individuals tend to reactivate their behavioral activation system. One of the mechanisms of reactivating their behavioral activation system is through violence. McGregor et al. (2015) argue that the means to reactivate the behavioral activation system may depend on relatively consistent individual characteristics, such as personality traits. In other words, certain individuals may endorse violence more than others, and these individuals may also be more likely to endorse (and engage in) political violence.

The recently coined “dark-ego-vehicle” principle provides an explanation that encompasses non-normative and normative collective actions. According to the principle, individuals with dark personality traits may use collective actions to satisfy their ego-related needs, such as the need for domination, sensation seeking, or positive self-presentation (Bertrams & Krispenz, 2024; Krispenz & Bertrams, 2024). In other words, the participation of individuals high on dark personality traits in collective actions focuses on their personal gains (which may or may not be related to ingroup goals) instead of improving the conditions of their ingroup.

Empirical evidence supports the presented theoretical explanations. A recent meta-analysis (Wolfowicz et al., 2021) highlighted various dark personality traits as risk factors for radicalized attitudes and intentions1, with relatively robust relationships across contexts (Nai & Young, 2024). Studies conducted in the Croatian context are aligned with this conclusion (Pavlović & Wertag, 2021; Pavlović & Franc, 2023).

Studies focusing on the relationship between activism and dark personality traits also highlighted their positive relationship. One analysis revealed that only narcissism was positively related to activism among politicians, although the strength of the relationship depended on partisan identity (Gotzsche-Astrup, 2021). This relationship was also confirmed by Rico-Bordera et al. (2023) and Bertrams and Krispenz (2024), although the latter authors focused only on narcissism. Rogoza et al. (2022) robustly confirmed the role of narcissism in activism, while the role of Machiavellianism and psychopathy depended on the context. In Poland, individuals scoring higher on Machiavellianism and psychopathy also achieved higher activism scores, while in the UK, these relationships were non-significant. Zacher (2024) also established a positive relationship between environmental activism and dark personality traits in a German sample, although the scale did not distinguish between normative and non-normative collective actions. Pavlović and Franc (2021) analyzed Croatian data and found a weak but positive relationship between activist intentions and general dark personality trait.

Altogether, the theories and their empirical evaluations agree on the relevance of dark personality traits in collective actions. However, as mentioned before, the presented literature speaks little of choosing between different actions. Also, the presented discussion ignores the role of gender, which has been recognized as a relevant correlate of dark personality traits (Muris et al., 2017) and collective actions (Pandolfelli et al., 2007; 2008).

Gender and collective actions

Although occasionally used as synonyms, sex represents one’s biological characteristics, while gender is socially determined and represents social behaviors and psychological characteristics ascribed to men and women (i.e., what it means to be a man or a woman or what is expected of men and women; Pryzgoda & Chrisler, 2000). These characteristics are transformed into rules (norms) maintained by different political, social, economic, and religious institutions that directly or indirectly praise the individuals following these rules and undermine those disobeying them. For instance, in some cultures, women are expected to take the role of caregivers and manage homes, while men take the role of suppliers and family leaders but also take roles in public activities such as collective actions (e.g., Bruce, 1989; Sen, 2000).

Pandolfelli et al. (2007; 2008) provided a conceptual framework for understanding the role of gender in collective actions. The authors first focus on contextual factors (factors existing independently of the action), explaining that people may have different (economic) backgrounds and vulnerabilities and are subject to different social expectations and laws, which may affect their decisions to engage in collective actions. Pandolfelli et al. (2007; 2008) argue that gender norms confining women to home management instead of society management impose strong constraints on their involvement in collective actions, just as more limited availability of (natural, economic, social, temporal or informational) resources stemming from reduced opportunities within a society due to the expected task of home management.

In societies where women are less independent, their partners and relatives may also affect women’s intention to engage in collective actions actively (e.g., by punishing women acting against their gender role) or passively (e.g., not providing support essential for women’s mobility and reduction of opportunity costs related to time). This dependency may be encompassed in social norms and laws, with the attempts to change these norms and laws being met with a backlash (see also Radke et al., 2016). All this risk of negative feedback may be a source of self-stigma among women, undermining their intentions to join collective actions.

Therefore, it is not surprising to see that women accepting conservative norms are less likely to engage in collective behaviors (Liss et al., 2004) and that viewers tend to consider women violating gender norms in a protest as more deserving of repression than women acting in line with traditional roles (Naunov, 2024). Additionally, women may be exposed to benevolent sexism – a patronizing expression of male dominance portraying women as the “better” sex requiring protection with the goal of serving the romantic needs of men – which also undermines their intention to participate in collective actions by presuming gender inequality and promoting traditional gender roles (Becker & Wright, 2011).

The action arena represents a central notion of the framework of Pandolfelli et al. (2007; 2008), encompassing actors, resources, and rules related to collective actions. The authors argue that men and women may perceive the action arena differently, resulting in different capabilities and motivations to join collective actions. Gender roles may affect the motivation to engage in specific actions and how women and men perceive their bargaining power. In cultures where women are subordinate to men, their bargaining power is perceived as lower. Furthermore, reduced opportunities and resources may undermine women’s capability to increase bargaining power. Reduced knowledge of politics (and specific issues related to the subject of collective action or just the perception of insufficient knowledge) and lack of experience in political debates may also undermine women’s bargaining power (Pandolfelli et al., 2007; 2008).

Radke et al. (2016) studied barriers women face when joining collective actions related to women’s rights from the perspective of SIMCA (Van Zomeren et al., 2008) and established multiple challenges that are relevant outside the context of women’s rights. As Pandolfelli et al. (2007; 2008), Radke et al. (2016) highlight the role of gender roles and sexism as relevant barriers to collective actions, as well as norms discouraging women from expressing anger that prevent them from escaping their traditional role of caregivers. Coffe and Bolzendahl (2010) also argued that gender roles and resource disparity may lie behind the gender differences in political behavior (other than voting).

It is worth noting that all the previous theoretical explanations are based on traditional gender roles. However, societal values have shifted, and gender roles have been challenged and at least somewhat modified by modernization (Campbell & Shorrocks, 2023; Shorrocks, 2018). More precisely, contemporary, more left-leaning women may be less likely to adhere to conservative participation norms, making a broader spectrum of collective actions available to them. The traditional gender differences and the shift in gender roles have gained empirical support even in newer international studies. For instance, Grasso and Smith (2022) and Dodson (2015) analyzed international data sets and confirmed that women are more likely to engage in non-confrontational political activities (such as petitioning, boycotting, or volunteering), while men are more likely to engage in confrontational activities and institutionalized political participation.

Additionally, Malmberg and Christensen (2021) found that, compared to women who consistently exhibited higher engagement in non-institutional forms of political participation, only men facing corruption exhibited a higher likelihood to engage in non-institutionalized forms of political participation. However, Dodson (2015) also established that women engage in a broader spectrum of collective actions in more egalitarian societies. Therefore, although it does not seem as large as before, the gender gap in collective actions may still exist, especially in more traditional societies.

Zooming in on Croatia

The context in which contemporary Croatian youth was raised can be described from multiple perspectives. This section describes the Croatian context from three perspectives that are most relevant to understanding its implications: the perspective of political life and the recent history of political scandals, the perspective of gender equality, and the perspective of collective actions in Croatia.

From the perspective of political life, Croatian citizens generally exhibit low trust in politicians and political institutions (Bovan, 2024; Bovan & Baketa, 2022; Franc & Međugorac, 2014; Gvozdanović et al., 2019; Sučić et al., 2018). Many potential sources of this distrust can be tracked, some of which may stem from clientelism and corruption occurring in its early years (Rimac & Štulhofer, 2004; see also Kulenović & Petković, 2016 for a more general overview). Contemporary Croatia is a democratic and parliamentary republic in which parliamentary elections are held every four years, and presidential elections are held every five years. Croatian citizens seem to put a stronger emphasis on historical legacy and group attachment compared to the actual program presented by potential presidents and political parties (Širinić et al., 2024; see also Vuksan-Ćusa & Raos, 2021).

In parliamentary elections, coalitions are formed to determine the winners and form a government. Two parties dominated the political scene in the first two decades of the country’s independence – the center-right Croatian Democratic Union (Hrvatska demokratska zajednica, HDZ) and the center-left Social democratic party of Croatia (Socijaldemokratska partija Hrvatske, SDP). While the governments organized by SDP-led coalitions were (dominantly) criticized for their reluctance (alongside several political affairs), the governments organized by HDZ-led coalitions were riddled with minor and severe corruption scandals that more often than not included active ministers (Kukec, 2020; Kulenović & Petković, 2016; Lalić et al., 2023). The described continuous stream of corruption enabled the entrance of anti-establishment political parties – such as The Bridge (Most) or Homeland Movement (Domovinski pokret) – into the political arena, which played an important role in the elections in the late 2010s and early 2020s by promoting distrust in “mainstream” politicians (Grbeša & Šalaj, 2017; Raos, 2023), while the new political scandals of HDZ-led government kept emerging (Lalić et al., 2023).

Altogether, next to Croatian courts slowly resolving earlier corruption affairs (thus reminding citizens of them) and contemporary affairs occurring in every government, citizens also observed how the oppositional parties rapidly shifted their opinions after getting an opportunity to enter the government (Grbeša & Šalaj, 2017). All this served as a basis for the belief that politicians are willing to sell out their beliefs (or even national interests) for money and power. Although youth is generally considered less interested in wider social problems (Ilišin et al., 2013), the combination of political affairs and rising populism was omnipresent during their political socialization and might have shaped the political attitudes of Croatian youth.

Regarding gender equality, Croatia belongs to the bottom third of the European Union, suggesting that gender inequality is not negligible. The aspects of inequality highlighted as suboptimal were knowledge (participation in education and training), time (gender gap in activities outside the home), and power (gender inequality in political and social institutions; European Institute for Gender Equality, 2023). These inequalities align with Pandolfelli et al. (2007; 2008) framework, suggesting that women in Croatian society may perceive higher costs of participation in collective actions than men, which may lead to less positive attitudes toward collective actions and weaker intentions to join them. The mentioned burdens may be especially detrimental for young women who may, next to the challenges of education and job attainment, have to struggle with the challenges of reproduction and childcare (Pandolfelli et al., 2007; 2008).

Regarding collective actions, the studies seem to agree that Croatian citizens are moderately active (although Croatian youth perceive Croats as passive and apathetic; see Bovan et al., 2018). Global protest tracker (2024) ranks Croatia in the middle of the list of 137 countries with respect to the number of (larger) protest activities. Multiple studies on the general population confirm this notion. Soler-i-Marti and Ferrer-Fons (2014) analyzed data collected on convenient samples of youth from 14 European countries within the project MyPLACE, with two samples being drawn from each country: one from a more affluent and another from a less affluent region (in Croatia: from a more affluent and less affluent part of Zagreb). Both samples from Zagreb were ranked in the middle of all samples with respect to protest participation, private individual political participation, and public political participation.

Sučić et al. (2018), based on an international data set on youth from five European countries collected within the project PROMISE, found that 17% of young Croats considered protests and demonstrations as the best ways of participation in the life of EU: this attitude was more often expressed among young men (22%) compared to young women (13%). While their attitudes on joining NGOs were similarly positive among young men and women, women were more likely to support the idea that individual actions are the best way to participate in the life of the EU. Outside the context of protests, another study conducted on a sample of Croatian high school students found that female students expressed slightly more positive attitudes toward NGOs than male students (Baketa et al., 2021). Maglić et al. (2022) found that Croatian high school students exhibited moderate intentions to participate in various collective actions (including boycotting products, signing petitions, and participating in demonstrations) aiming to protect the environment, with women exhibiting stronger intentions to participate compared to men.

On the other hand, Pavlović and Franc (2021) did not establish any differences in activist intentions between men and women on a quota-representative sample (with respect to age and gender) of Croatian adults. In general, young Croats may be more likely to engage in forms of participation that require fewer resources (such as signing petitions or following online posts) compared to more traditional forms of participation (Mrakovčić et al., 2019). It is also worth noting that the mentioned gender differences may be specific to collective actions – young men and women report similar levels of electoral participation (Širinić & Dolenec, 2024).

Results on radicalized attitudes and intentions are scarcer and, in most cases, suggest that young Croats do not accept political violence. Studies conducted only in the Croatian context found that youth generally disagree that some social conflicts can be solved only with violence (Gvozdanović et al., 2019). Also, female students exhibited less positive attitudes toward political violence, while women exhibited weaker radicalized attitudes compared to men (Pavlović & Franc, 2021). Croatian youth generally perceive radicals as individuals attempting to achieve substantial changes, contrasting them to the mainstream and holding negative opinions about them, although they do not emphasize the connection between radicalism and political violence (Bovan et al., 2018). However, international research reveals a less consistent image. For instance, Ellison et al. (2014) established that young Croats from Zagreb were among the most supportive of political violence based on the MyPLACE data set, while Storm et al. (2020) found that (young) Croats were among the least supportive of political violence based on the representative European Value Survey data from 2017.

The aim of the study

This study approaches the question of collective actions in line with the recent prominent models agreeing on the relevance of the distinction between radicalized attitudes and behaviors (Khalil et al., 2019; McCauley & Moskalenko, 2017), which was also incorporated in a recent systematic review (Franc & Pavlović, 2021) and meta-analysis (Wolfowicz et al., 2021). These theoretical models presume that attitudes and intentions (and behaviors) are not directly related and that knowing someone’s attitudes on collective actions does not provide trustworthy information about his or her intentions to act. This distinction is important as most earlier analyses did not provide insight into whether the drivers of violent collective actions are the same as drivers of collective actions in general (Franc & Pavlović, 2021).

Therefore, next to distinguishing between activist and radicalized collective actions, the study also distinguishes between attitudes and intentions related to these two types of actions. A recent study by Pavlović & Franc (2022) revealed that classifications of participants with respect to participation in non-normative collective actions based only on measured attitudes at best scenario misclassifies only a third of the sample, representing a substantial lack of precision. Recently, the measurement of radicalized (and activist) intentions has attracted the attention of researchers and was declared one of the pathways to future research on political violence (Gøtzsche-Astrup et al., 2020).

To avoid potential biases in conclusions based on the correlation between activist and radicalized intentions, the main goal of this study was to establish latent profiles of Croatian youth with respect to radicalized and activist attitudes and intentions and to compare these profiles with respect to the general dark personality trait while taking gender into account. Latent profile/class analyses represent analytical approaches aiming to distinguish participants based on their responses to a set of items (Spurk et al., 2020) or, metaphorically speaking, to “unscramble the eggs” (Oberski, 2016). The latent class analysis was already applied to the data of the Activism and Radicalism Intentions Scale (Moskalenko & McCauley, 2009) collected on two samples (US students and prisoners), which yielded five classes: passive (low activist and radicalized intentions), moderate activists (moderate activist and low radicalized intentions), strong activists (high activist and low radicalized intentions), radicals (high activist and radicalized intentions), and a mixed class (a class of individuals not belonging to any other class, “uncertains”; Pavlović et al., 2024).

Based on the earlier literature (Pavlović et al., 2024), it was expected to establish at least the profiles of activists, radicals, and passive citizens among male and female students. Due to methodological differences, we did not expect to establish the “mixed” profile (“uncertains”). Based on the expected profiles and presented literature on collective actions and dark personality traits, radicals were expected to exhibit higher general dark personality scores than the other two profiles. Based on the expected profiles and presented literature on collective actions and gender, men were expected to exhibit higher radicalized, but not necessarily activist intentions and attitudes compared to women (as activism may be related to lower opportunity costs compared to radicalism). In other words, a higher proportion of men is expected to belong to the radicals profile than women. Additionally, the literature describing higher opportunity costs suggests that the higher proportion of women (compared to men) should be classified as passive.

Participants

Data analyzed in the study were collected within a broader research project in September and October 2021. The final (convenient) sample (see Procedure) consisted of 727 university students (53% women) who were, on average, 21.5 years old (SD = 2.3). The male and female subsample were similar with respect to age (t(717.2) = 1.38, p = .017), years of completed education (t(695.6) = -0.13, p = .897), and economic status (t(700.35) = 1.76, p = .080). Although women exhibited slightly more left-leaning political attitudes compared to men (χ2(727) = 8.71, p = .033), the magnitude of the difference was negligible (Cramer V = .11). Most of the students were studying at the faculties of the University of Zagreb and University of Osijek.

Measures

The study measured attitudes and intentions to participate in collective actions related to goals aligned with populist ideas – participants' attitudes and intentions related to actions against unjust politicians. This decision was based on the SIMCA model, which highlights efficacy, identification, and injustice as primary drivers of collective actions (Van Zomeren et al., 2008). Adapting measures in the form of citizens versus unjust politicians allowed clear group distinction and a sense of injustice (as the focus was on actions aiming only at unjust politicians, not all politicians or even all members of any political party or government). Therefore, the focus on actions towards those politicians perceived as unjust (instead of declaring that all politicians or all members of a specific party represent a homogeneous and unjust group; see also Akkerman et al., 2014; Mudde, 2004; Wettstein et al., 2020) separates measures used in this study from usual anti-establishment and populist measures.

Activism and Radicalism Intentions Scale2 (Moskalenko & McCauley, 2009) was adapted to operationalize activist and radicalized intentions. The scale consists of eight items: four measuring activist intentions and four measuring radicalized intentions. As the data were collected during the COVID-19 pandemic, items including public gatherings were modified in two ways. Firstly, the fourth activism item was replaced with an item, “I would try to persuade others to join an organization…”. Secondly, the same items were used to measure activist and radicalized intentions and the only difference was the organization for which actions were conducted. When reporting activist intentions, participants reported the probability of participating in actions for an organization that attempts to achieve political goals peacefully. On the other hand, when reporting radicalized intentions, participants reported the probability of participating in actions for an organization that attempts to achieve political goals using violence. Participants responded to items on a 1 to 6 scale, with a higher value indicating a higher probability of participating in a specific political activity. Internal consistency (ωactivist intentions = .92, ωradicalized intention = .88) and model fit (robust CFI = .971, robust RMSEA = .082, 95% CI [.062, .103], SRMR = .030) of scales was acceptable. The higher scores indicated stronger activist and radicalized intentions, respectively.

Radicalized attitudes were measured using an adapted version of Kalmoe’s (2014) questionnaire. The adapted scale consisted of four items measuring support for various forms of political violence (e.g., “When politicians are creating or broadening inequality, citizens should send threats to scare them straight.”). Participants responded on a 1 to 6 scale, with higher values indicating a higher agreement with the statement. Internal consistency of the scale was acceptable (ω = .83), as well as model fit (robust CFI = .991, robust RMSEA = .079, 95% CI [.032, .134], SRMR = .018). The higher scores indicated stronger radicalized attitudes.

Activist attitudes were measured using four items developed for a broader research project (e.g., “Voting is the best way to prevent politics that create or broaden social inequalities”) based on the Activist orientation scale (Corning & Myers, 2002). Participants responded to items on a 1 to 6 scale, with higher values indicating a higher agreement with the statement. Internal consistency of the scale was slightly suboptimal (ωactivist attitude = .67), while model fit was marginally acceptable (robust CFI = .954, robust RMSEA = .138, 95% CI [.088, .194], SRMR = .044). The higher scores indicated stronger activist attitudes.

All four previously described variables were used as indicators in latent profile analysis. Their scores were obtained from a single model that achieved acceptable fit (robust CFI = .960, robust RMSEA = .055, 95% CI [.047, .063], SRMR = .060).

The general dark personality trait was measured using the D16 questionnaire (Moshagen et al., 2020). The scale consists of sixteen items (half reverse-coded, e.g., “Most people deserve respect”). Participants responded on a 1-5 scale, with higher values indicating a higher agreement with the statement. The single-factor solution exhibited acceptable model fit (robust CFI = .799, robust RMSEA = .071, 95% CI [.064, .078], SRMR = .061) and internal consistency (ω = .79). Higher scores of the latent factor (after reverse-coding) indicated higher scores on the general dark personality trait.

Studied socio-demographic variables included gender (male, female, other), age, years of completed education, and perceived economic status measured on a five-level scale ranging from “significantly below average” (1) to “significantly above average” (5), with the midpoint (3) denoting “average.” Additionally, political orientation was measured on a 0-10 scale with higher values indicating a more right-leaning orientation. Participants could declare they were “indecisive” (value 99) regarding political orientation. Before analyses, the variable was recoded into four categories (0-3 = left, 4-6 = center, 7-10 = right, 99 = indecisive).

Procedure

Data were collected within a broader project in line with the ethical standards (confirmed by the [institution] ethical committee) on a convenient sample of youth from Croatia. University students were invited to participate in the study via mailing groups of different faculties of the University of Zagreb and the University of Osijek. The link with the invitation to participate was also disseminated in general Croatian student groups and forums, which enabled students of other universities to participate in the study. Student part of the sample originated from various faculties, with students of sociology, political science, and psychology (disciplines most relevant for this type of research that might affect the quality of results due to potential familiarity with measures and additional exposure to related contents during studies) making up only a small fraction of the sample (combined N = 33 or 4% of the total sample). The non-student sample was invited to participate in the study via various activist and non-activist groups and social media sites. Participants completed the questionnaires online and received no financial compensation for their efforts.

Data were analyzed using R (R Core Team, 2024), dominantly by relying on functions from packages lavaan (Rosseel, 2012), semTools (Jorgensen et al., 2018), and tidySEM (Van Lissa, 2023). Data (N = 1048) was cleaned in multiple steps. In line with the information in the informed consent, data of all participants who stopped completing the questionnaire was not used in analyses, leaving us with 922 participants. Participants providing the same response to more than ten items in a row were also excluded (N = 12), along with non-binary participants (N = 9) and participants younger than 18 and older than 29 due to our focus on youth (N = 78). Finally, non-students (N = 96) were excluded from the main analyses to increase the homogeneity of the studied sample (as the subsample of non-students was not large enough for a separate analysis). This left us with the final sample consisting of 727 participants. Latent profile analyses were conducted in line with the recommendations made by Van Lissa et al. (2024), including the follow-up analyses that relied on the BCH (Bolck et al., 2004). Gender-invariant factor scores of radicalized and activist attitudes and intentions were used as indicator variables in forming profiles. As one of the research goals was to evaluate gender differences, the question of measurement also had to be taken into account: the comparability of factor scores was ascertained following the guidelines described by Putnick and Bornstein (2016), with a primary focus on Satorra-Bentler corrected chi-square tests (Satorra & Bentler, 2001; Satorra & Bentler, 2010), which the invariance of the outcomes of latent profile analyses was evaluated in line with Morin et al. (2016).

Results

The overview of results starts with a table of descriptive statistics (Table 1), which reveals that participants generally exhibited stronger activist attitudes and intentions than radicalized ones. Participants scored low on the general dark personality (in line with Pavlović, 2023; Pavlović & Wertag, 2021). The calculated skewness scores do not suggest any deviations strong enough to severely bias the scores (George & Mallery, 2010).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics based on POMS (proportion-of-maximum-possible) scores of key variables of this study (N = 727)

In the following step, latent profile analysis with equal variances and no covariances (mimicking the local independence assumption, see Oberski, 2016) was conducted, evaluating one- to ten-profile solutions. This range of studies solution was based on the outcomes of an earlier latent profile analysis, which yielded five classes (Pavlović et al., 2024), while the additional profiles were tested due to the addition of attitudinal variables. These outcomes are exhibited in Table 2.

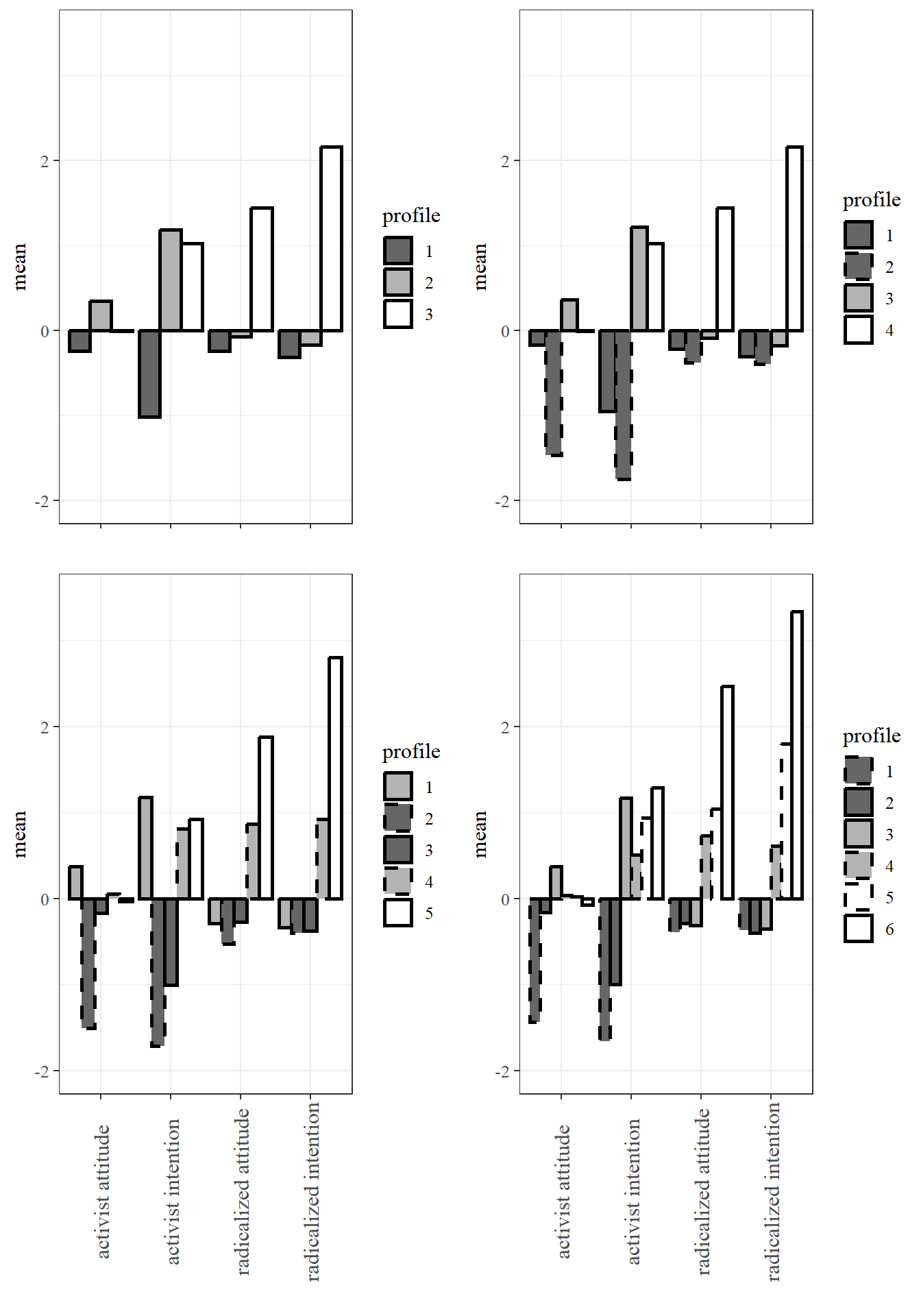

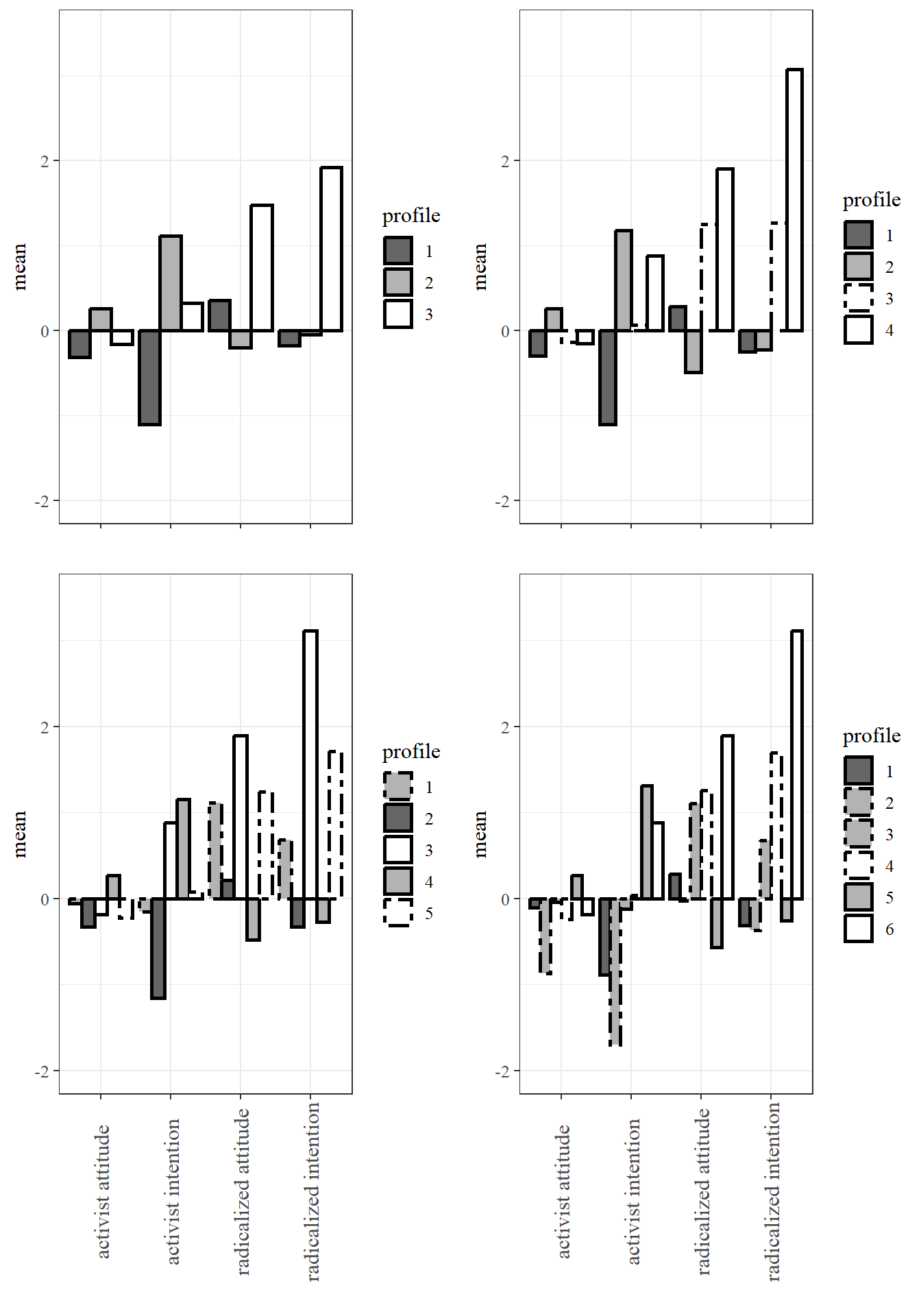

In line with the earlier evidence of the robustness of BIC (Nylund et al., 2007), it was selected as the main source of information regarding the retention of profiles, along with the outcomes of the Lo-Mendell-Rubin (LMR) likelihood ratio test. The BIC of the solution with five profiles in male and six profiles in female subsamples was followed by increased BIC. Outcomes of the LMR test comparing five and six profiles among men were barely significant (only at α = .05), while ω2 suggested that adding even the fifth profile would provide a negligibly distinctive contribution. Similarly, ω2 suggested that adding a sixth profile among women would undermine profile distinctiveness. Despite the excellent entropy scores following the selected number of profiles, the size of the smallest profile and profile development throughout analyses were considered to ensure that the retained profiles have substantive meaning. The development of profiles is visualized in Figures 1 and 2. Among women, the sixth profile represents a midpoint between two other profiles high on radicalism. Among men, the smallest profile of the five-profile solution was the profile with the highest scores of radicalism items. A version of this profile is also present in the three- and four-profile solution, albeit less refined. The combination of insignificant ω2 and questionably distinctive profiles made the four-profile solution seem most appropriate to describe the male subsample and the five-profile solution to describe the female subsample.3

Figure 1. Outcomes of latent profile analyses among female students

Figure 2. Outcomes of latent profile analyses among male students

Multiple similar profiles were observed in the male and female subsample. Analyses conducted on both female (48% of subsample: profile 3, average posterior probability (APP) = .90) and male (56% of subsample: profile 1, APP = .94) subsample yielded a profile of passive individuals. This profile is characterized by low scores on all four indicators among women. Similar scores were found among men, who exhibited slightly above-average scores of radicalized attitudes and low scores on remaining indicators.

The analyses also yielded a profile of activists in the female (30% of subsample: profile 1, APP = .89) and male (13% of subsample: profile 2, APP = .87) subsamples. This profile was characterized by elevated scores of activist attitudes and intentions and low scores on radicalized attitudes and intentions.

Additionally, the analyses on both subsamples yielded a profile of strong radicals – individuals high on activist intentions and radicalized attitudes and intentions. Their scores on activist attitudes were close to the midpoint among women (6% of subsample: profile 5, APP = 1) and slightly below the midpoint among men (6% of subsample: profile 4, APP = .98) subsample.

A profile of moderate radicals was established on the female (14% of subsample: profile 4, APP = .98) and male (24% of subsample: profile 3, APP = .93) subsamples. Among women, this profile was characterized by average scores on activist attitudes and elevated (but not extreme) scores of activist intentions and radicalized attitudes and intentions. Similar profiles were established among men, although average activist intentions characterized the profile.

Finally, the analyses yielded a profile of passive individuals with negative attitudes on activism in the female subsample (negative passive; 2% of subsample: profile 2, APP = .90). While this profile occurred among women even in the four-profile solution and consistently occurred in later refinements, a similar profile can be found among men as profile 2 in the six-profile solution. Although potentially interesting, the occurrence of this profile after the BIC threshold suggests its questionable replicability (or insufficient statistical power for its clearer identification) in the male subsample.

The proportions of participants belonging to each profile were compared in the following step. The proportion of women belonging to the two passive profiles was slightly lower compared to that of passive men (z = -2.26, p = .024, h = .17). A larger proportion of women was categorized as activists than men (z = 5.36, p < .001, h = .41). A slightly lower proportion of women was categorized as moderate radicals compared to men (z = -3.56, p < .001, h = .27). A similar proportion of men and women was categorized as strong radicals (z = 0.10, p = .924, h = .01).

Considering the briefly discussed differences in the retained number of profiles, indicator means between comparable profiles, and differences in the proportion of participants belonging to each profile, it becomes evident that Morin et al. (2016) assumptions of profile invariance have not been met. In practice, this means that men and women share some patterns of thoughts and intentions related to political actions, but they are not identical and should be compared with a dose of caution.

In the follow-up analyses using the BCH procedure (Bolck et al., 2004), these profiles were compared with respect to the general dark personality trait scores that achieved partial strong invariance (for details, see Supplementary materials 1). Next to presenting the profile means, Table 3 also presents the (uncorrected) significance of pairwise tests.

Among men, activists achieved the lowest scores on the general dark personality trait – lower than the remaining three latent profiles (although the difference between strong radicals and activists was not established due to reduced statistical power). However, among women, moderate and strong radicals achieved higher scores on the general dark personality trait (D) than activists and passive individuals. No differences were established with the profile of negative supporters among women. To evaluate the robustness of findings, the analyses were reconducted with D calculated as item average (after reverse-coding relevant items). The findings were nearly identical (see Supplementary materials).4

Table 3. Differences in the general dark personality trait (D) with respect to latent profiles of activist and radicalized attitudes and intentions

Note. P-values of pairwise comparisons are marked with asterisks. *p < .05, ** p < .01, ***p < .001

Discussion

This study provided many relevant insights into Croatian students’ political attitudes and intentions. Furthermore, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study applying latent profile analysis on attitudes and intentions simultaneously. This represents a unique contribution to the concurrent literature on collective actions. The study confirmed the relevance of distinguishing between activist and radicalized attitudes and intentions (the profile of activists vs. the profiles of radicals) and provided evidence in favor of distinguishing between attitudes and intentions in the context of collective actions (the profile of passive individuals vs. the profile of negative passive individuals among women). Such findings are aligned with contemporary models of radicalization advocating the distinction between activism and radicalism, as well as the distinction between attitudes, intentions, and behaviors (McCauley & Moskalenko, 2017; Khalil et al., 2019), and represent a way forward in studying collective actions that might help researchers discern the drivers of violent collective actions from drivers of collective actions in general (Franc & Pavlović, 2021).

In general, the analyses established the relatively consistent presence of four latent profiles based on activist and radicalized attitudes and intentions, which partially confirms and extends the conclusions made by Pavlović et al. (2024), even when participants' gender was taken into account. More precisely, as in Pavlović et al. (2024), profiles of “strong” activists (in this study: activists), passive, and radical (in this study: strong radical) individuals were established. Unlike Pavlović et al. (2024), we established profiles of moderate radicals and a profile of negative passive individuals among women, which represent a unique contribution of this study as these profiles were impossible to estimate without measuring and analyzing attitudes and intentions simultaneously. In line with the expectations, we did not establish the profile of “uncertains” (entropy and APP values were relatively high), which could be attributed to the subtle differences in methodological approaches and the addition of attitudes as indicators.

Additional comparisons revealed that men and women were equally likely to be categorized as “strong” radicals. At the same time, the difference established in the proportion of passive individuals was statistically significant but of negligible practical meaning (effect size), which is not in line with the expectation that women are more passive than men (Pandolfelli et al., 2007; 2008). However, if we consider collective actions as a dimension ranging from “doing nothing” (passive) to “doing anything” (radical), the notion that the two extremes do not differ substantially with respect to gender is not completely surprising. While due to the distrust in (political) institutions (Franc & Međugorac, 2014; Sučić et al., 2018;) a portion of Croatian youth may be disinterested in politics and collective actions, the other extreme may completely disregard any threats (including opportunity costs and other risks) related to collective actions, which eliminates gender differences. Non-negligible gender differences, however, emerge between the described extremes: women were more likely to be categorized as activists, while men were more likely to be categorized as moderate radicals. Considering the profiles of strong and moderate radicals together, these findings align with the expectation that men, on average, exhibit stronger radicalized but not activist intentions and attitudes compared to women.

Furthermore, these findings are aligned with the research on the general population, suggesting that men are more likely to endorse non-normative, confrontational, or violent actions (Chermak & Gruenewald, 2015; Grasso & Smith, 2022; Pavlović & Wertag, 2021), which women may feel reluctant about due to their perception of risks (Pandolfelli et al., 2007; 2008). On the other hand, peaceful protests, signing petitions, or volunteering are generally not considered risky in Croatia and represent the modus operandi of many Croatian NGOs. Therefore, women may hold positive opinions and intentions to engage specifically in such activities more often than men (see also Baketa et al., 2021; Grasso & Smith, 2022). Altogether, gender differences among students in attitudes and intentions related to collective actions in Croatia seem to emerge dominantly with respect to the choice of actions (with the exception of extremes, which are equally present among men and women). Nevertheless, additional studies are required to evaluate the extent to which treating moderate and strong radicals as equivalent is justified.

Moreover, the established prevalence of radical profiles (which make up about one-fifth of the female subsample and almost one-third of the male subsample) is not completely in line with other studies suggesting that the majority of citizens condemn political violence (Berntzen et al., 2024; Storm et al., 2020; Westwood et al., 2022). This discrepancy might be an artifact of measurement: this study focused on political violence towards unjust politicians – politicians whose actions create or broaden inequality, while broader international surveys (such as the European Value Study) often measure support for political violence using a single, generic item (which may evoke the impression of measuring support for terrorist attacks on civilians only). Therefore, the results of this study may not be directly comparable to other studies due to the format of criteria, which also limits the use of these findings in estimating the level of radicalization in Croatia. Nevertheless, radicalized attitudes and intentions should not be taken lightly as some (rare, but not irrelevant) citizens may consider them as an encouragement to participate in a violent act (McGregor et al., 2015).

Understanding political attitudes and intentions also implies understanding their determinants, which leads to the general dark personality trait. More precisely, female radicals exhibited higher general dark personality trait scores than other profiles, aligning with the dark-ego-vehicle principle (Bertrams & Krispenz, 2024; Krispenz & Bertrams, 2024). However, this was not established for female and male activists. Furthermore, the profiles of radical men exhibited higher dark personality scores only compared to activists, with passive individuals scoring as high on the general dark personality trait as radicals. These findings are not in line with earlier research (Pavlović & Franc, 2021) nor with contemporary models of radicalization that presume the interaction between dispositional and contextual factors of radicalization (McGregor et al., 2015; Pisoiu et al., 2020). A potential explanation may lie in the nature of the general dark personality trait.

Namely, while this trait represents common aspects of many dark personality traits, their specific aspects are neglected. If we consider that different explanations of the relationship between dark personality traits and radicalized attitudes and behaviors exist (Pavlović & Wertag, 2021; Nussio, 2020), the obtained inconsistency may reflect the complex nature of dark personality traits. For instance, its antisocial (in terms of disinterest in group well-being and collaboration) aspects may affect one’s intention to join groups. In contrast, impulsive and aggressive aspects might be related to support for violence. While passive men might be more antisocial and aggressive, radical men might be more aggressive and impulsive but not as antisocial, which could lead to a discrepancy in the overall score. Altogether, results are only partially in line with the dark-ego-vehicle principle (Bertrams & Krispenz, 2024; Krispenz & Bertrams, 2024): while these results do not imply the principle is wrong, the analyses suggest that the principle may be more applicable to non-normative and violent political actions (among women). Additional research is required to provide more robust arguments in favor or against this potential limitation on the dark-ego-vehicle principle. Nevertheless, current findings suggest that (at least the majority of) activists do not engage in activism only to satisfy their ego-related needs, which may contribute to the destigmatization of activism as a form of political participation by undermining one of its potential barriers – a negative attitude towards activists (Bashir et al., 2013).

As Pavlović et al. (2024), this study also failed to establish the profile of individuals exhibiting radicalized attitudes and intentions who do not exhibit activist attitudes and intentions. Again, this might be considered an encouraging finding, suggesting that radicals generally endorse activism. In other words, if radicals have a full spectrum of political actions available (instead of only violent actions), one aspect of preventing political violence would be to emphasize and increase the accessibility of available non-violent political actions. As Franc et al. (2023) described in their study of Catalan protests in 2019, a large violent potential of the movement was released only after Catalan leaders were sentenced – until then, all the individuals who later participated in violent riots were acting in line with the non-violent norms of political participation. The question of accessibility also raises the question of citizens’ political literacy (e.g., whether citizens know whom to report a problem, how that institution works, what its limitations are, etc.), which could represent relevant information for prevention programs conducted in educational contexts.

Several limitations of this study should also be acknowledged. Firstly, the correlational study implies that additional research is necessary before establishing causal conclusions. Secondly, the analyses were based on a sample from a single cultural context (during the COVID-19 pandemic), implying that additional research is required to evaluate whether the newly established profiles of supporters and two profiles of radicals can be replicated in other contexts. The combination of a specific context and non-representative sample may have biased the true proportions of the established latent profiles in Croatian society (and hindered the probability of detecting other potentially relevant profiles). Thirdly, this study focused on overall attitudes and tendencies rather than specific attitudes and tendencies on actions occurring in a specific context (e.g., intentions to join an initiative that prepared protests after some politician’s illegal affairs have been published). Therefore, reevaluating these results using materials relying more on actual context would provide valuable evidence on the ecological validity of these findings.

Additional robustness would be provided by re-evaluating these results in the context of different political goals (e.g., protests related to climate change, LGBTQ rights, or gender equality) as measures used in the study dominantly focus on attitudes and intentions related to unjust politicians, in line with the populist rhetoric. In other words, although this study provides valuable insights into the relationships between activist and radicalized attitudes and intentions, additional research (ideally on a representative sample) is required before generalizing these results to other political subjects. Finally, although we established multiple profiles, this study was not focused on the transition between profiles, implying that some of these profiles may represent stages of a process while others represent different outcomes that may emerge due to specific factors.

Despite its limitations, this study provided many relevant insights into Croatian students' activist and radicalized attitudes and intentions. Along with confirming some of the classes established in earlier research, this analysis uncovered some new latent profiles overlooked by the earlier analyses. Additionally, these profiles differed with respect to the general dark personality trait in line with contemporary theories and earlier research (among women), but also in an unexpected way (among men), implying the relevance of including gender in studies of political attitudes and intentions, which could lead to more refined theories and models, as well as more effective preventive strategies and interventions.

Table 4. Original items used in the main analyses

Note. * reverse-coded item.

References

Franc, R. & Međugorac, V. (2014). Attitudes and trust. In: M. Ellison & G. Pollock (Eds.), WP4: Measuring Participation: Deliverable 4.6: Europe-wide thematic report. MYPLACE (Memory, Youth, Political Legacy And Civic Engagement, FP7-26683) (pp. 97-126).https://www.academia.edu/20058980/Attitudes_and_Trust

Ilišin, V., Bouillet, D., Gvozdanović, A., & Potočnik, D. (2013) Youth in a Time of Crisis. Zagreb: Institut za društvena istraživanja.

Kalmoe, N. P. (2014). Fueling the Fire: Violent Metaphors, Trait Aggression, and Support for Political Violence. Political Communication, 31(4), 545-563.https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2013.852642

Sučić, I., Dević, I., & Franc, R. (2018). Croatia. PROMoting youth Involvement and Social Engagement: Opportunities and challenges for ‘conflicted’ young people across Europe: National research report level 2 (pp. 204-224).https://www.promise.manchester.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/National-reports-using-secondary-data-analysis-by-GESIS-May-2018.pdf

Van Lissa, C. J., Garnier-Villarreal, M., & Anadria, D. (2024). Recommended practices in latent profile analysis using the open-source R-package tidySEM. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 31(3), 526-534.https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2023.2250920

Zacher, H. (2024). The dark side of environmental activism. Personality and Individual Differences, 219, 112506.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2023.112506

Rod i mračne crte ličnosti kao odrednice sudioništva u kolektivnom djelovanju: pogled iz Hrvatske

Sažetak Ova je studija usmjerena na više ciljeva. Prvi cilj je proširiti bazu podataka i ponuditi uvid u obrasce stavova i namjera vezanih uz aktivizam (normativno kolektivno djelovanje) i radikalizam (nenormativno i nasilno kolektivno djelovanje) među mladima u Hrvatskoj. Drugi cilj je testirati načelo mračnog ega kao pokretača (dark-ego-vehicle) procjenom razlikuju li se profili temeljeni na obrascima stavova i namjera vezanih za kolektivno djelovanje značajno s obzirom na opću mračnu crtu ličnosti. Podaci za 727 hrvatskih studenata (53% žena) analizirani su analizom latentnog profila, koja je otkrila četiri profila u muškom i pet profila u ženskom poduzorku. Većina profila (pasivni, aktivisti, umjereni radikali, intenzivni radikali) uspostavljena je među muškarcima i ženama, sa zanemarivim razlikama u srednjim vrijednostima indikatora. Međutim, pokazalo se vjerojatnijim da muškarci budu kategorizirani kao umjereni radikali (uz nešto više vjerojatnosti da će biti kategorizirani kao pasivni), dok su žene češće bile kategorizirane kao aktivistice. Studija je djelomično poduprla načelo mračnog ega kao pokretača među ženama: dok su aktivistice imale niske rezultate u pogledu mračnih crta ličnosti, umjereni i intenzivni radikali pokazali su više rezultate. Među muškarcima, aktivisti su također imali nisku ocjenu na crtama mračne ličnosti, za razliku od pasivnih pojedinaca, umjerenih i intenzivnih radikala.

Ključne riječi aktivizam, radikalizam, političko nasilje, spol, analiza latentnog profila

|

How to cite this article / Kako citirati članak: Pavlović, T. (2024). Gender and Dark Personality Traits as Determinants of Collective Action Participation: A View from Croatia. Anali Hrvatskog politološkog društva, 21(1): 65-91.https://doi.org/10.20901/an.21.10 |