INTRODUCTION

Wine tourism has been defined as the “visitation to vineyards, wineries, wine festivals and wine shows for which grape wine tasting and/or experiencing the attributes of a grape wine region are the prime motivating factors for visitors” (Hall, Longo, Mitchell, & Johnson, 2000). It is usually associated with the appeal of wineries and the wine country as a whole, and is seen as a form of niche marketing and destination development, on the one hand, and an opportunity to increase sales and revenues on the part of the wine industry on the other. Wine itself is increasingly seen as a cultural good (Marks, 2011) and as such can be used to contribute to improving destination image.

One of the forms in which wine tourism is practiced is through organized wine tours. Although an increasing number of tourists arrange the details of their trip by themselves, tour operators and travel agencies are still preferred by a significant number of customers, especially for international travel. The growing independency of tourists, however, results in increased levels of competition and subsequent diversification and/or specialization of offering, and a search for innovative product design. Wine tourism packages offered by tour operators form a relatively smaller share compared to FITs (Fully independent travelers); yet, they are an important revenue source for wineries and an opportunity for the whole wine region. There are various forms which the package may take – escorted or self-guided, duration may vary from one day to two weeks or even more, the size of the group might be larger than 10 persons or it may be an individual experience. Target groups may be foreign or domestic tourists and additional attractors range from cultural and natural heritage to adventure and even shopping. In terms of visitor origin, most studies report a ratio of 40%-60% for international and domestic visitors respectively (Science and Technology Park for Tourism and Leisure of Catalonia, 2012), although figures may vary for different destinations. As reported in a study on Australian wine tourism, Semi-independent travelers (SITs, 47%) and fully-independent travelers (FITs, 34%) form the largest shares of international wine tourists with tour group and package travelers counting for 19% of the total number (Tourism Research Australia, 2014).

This paper looks at organized wine tours, attempting to identify the main trends and the various forms they take. The study combines quantitative and qualitative analysis, drawing data from the official websites of specialized travel agencies and tour operators, and is clearly divided into two sections: the first one is dedicated to identifying global trends in wine tour design, while the second one is focused on the current situation in Bulgaria. Following a difficult restructuring from a centrally-planned to a market-oriented system in the 1990s, the wine industry in the country underwent a decade of decline before gaining positions on both international and domestic markets and can be used as an exemplifier of an emerging wine tourism destination in its earliest stage of development. According to the Executive Agency on Vine and Wine (EAVW, 2017), by October 2017 there were 259 registered wine producers in Bulgaria, around one-third of which offer wine tasting. Most of these were established after the year of 2000, and a lot of new wineries are still being opened each year. Despite this positive trend, the share of wineries involved in tourism is still small compared to other emerging wine destinations – Alonso and Liu, for example report a share of 81 per cent in West Australia (Alonso & Liu, 2010). In terms of wine production, the country usually ranks among the top 10 wine producers in Europe and exhibits slow growth for the period from 2014 to 2018 (Eurostat, 2018). Although the country is mainly popular as a sea-side destination, a recent study by Dimitrov et al claims that culture (a part of which is wine and wine-related activities) is the key factor of its attractiveness (Dimitrov, Stankova, Vasenska, & Uzunova, 2017).

1. LITERATURE REVIEW

Wine tourism first started to attract the attention of academics in the beginning of the 1990s, and since then, the topic has been a subject of increasing interest. Mitchel and Hall identify seven major themes discussed in literature: the wine tourism product and its development; wine tourism and regional development; the size of the winery visitation market; winery visitor segments; the behavior of the winery visitor; the nature of the visitor experience; and biosecurity risks posed by visitors (Mitchel & Hall, 2006). A much broader grouping is suggested by Kunc – wine tourism as a product and winery visitation as the behavior of wine tourists (Kunc, 2010). If we are to place the subject of this study within these frames, it will be part of the wine tourism product research, but will also be informed by visitor motivation and visitor experience studies.

Research on organized wine tourism is limited; in fact it is only sporadically mentioned when discussing the organized/ individual ratio for winery visits (Tourism Research Australia, 2014). One of the few studies on the topic - a paper on the activities of tour operators in Bulgaria (Terziyska & Kyurova, 2014), reports that approximately 13% of agencies specializing in cultural tourism include wine and gourmet in their tours. Given the scarcity of research dedicated specifically on wine tours, this literature review will be focused on the factors that impact wine tour design – wine visitor motivation, wine tourist profiles and typologies and the demand for wine tourism on the whole.

Visitor motivation in wine tourism has been largely researched. In 2004, based on review of previous studies, Alant and Bruwer identify the following motivating factors as primary: tasting wine, having a nice tasting experience, buying wine, enjoying different wines, finding a unique wine, and finding interesting and special wines, while motivations such as finding information, socializing, having a day out, eating at winery, meeting the wine-maker, picnic/BBQ, entertainment and rural setting were found to be secondary (Alant & Bruwer, 2004). Obviously, wine stands at the core of tourist motivation, with a focus not only on quality, but also on differentness, uniqueness and local character (which are actually interconnected). This was to a great extent confirmed in a more recent study byGrybovych et al. (2013), who identified almost the same set of motives but grouped them into three factors: Factor 1 – to learn about the wine and winemaking process, Factor 2 – to gain authentic Northeast Iowa experience, Factor 3 – to enjoy having a good time. The importance of the educational aspect was also revealed in a study on Greek wine tourists, where learning about wine and wine making was identified as the second strongest motive (Alebaki and Iakonidou, 2010).Marzo-Navvaro and Pedraja-Iglesias (2012) added to these another element – the cultural product, whileBruwer and Rueger-Muck (2018) emphasized the hedonic nature of wine tourism motivation. The findings of a study carried out in Serbia (a neighboring country of Bulgaria) in 2016 seem to give more emphasis on the core wine product: visit wineries, tasting wine, buying wine, trying out different types of wine, meeting wine producers, obtaining information about wine and its production, and the only motivations outside wine are tasting local food and organization of the trip (transport, accommodation, activities) (Sekulić, Mandarić, & Milovanović, 2016). The latter (organization of the trip) is directly related to organized wine tours and could be part of the pull factors: when speaking of less known destinations, tourists might be attracted by the provision of well-designed organized tours.

A well-structured instrument for identifying wine tourism motivation, which forms a solid basis for segmentation, was offered by Quintal et al. (Quintal, Thomas, Phau, & Soldat, 2017). It consists of six factors with 18 push-pull winescape attributes, resulting in four groups of wine tourists: inspireds, self-driven, market-driven, and inerts.

As in all other businesses, consumer profiling is essential for wine tour design and predestines the variety of tours targeted to different segments. Most typologies of wine tourists are based on their motivation, knowledge, lifestyles, and wine involvement. One of the most cited typologies (wine lovers, wine interested, and wine curious), for example, is based on interest in wine (Hall C. M., 1996). Some authors distinguish between subjective and objective segmentation bases (Molina, 2015).

A study that is particularly informative for wine tour design is the one conducted by the Australian government, as it profiles food and wine tourists according to their interest in wine and preferences to holiday activities. The authors identify 5 distinct types, as follows (Tourism Research Australia, 2014):

Low interest - Interest in food and wine tourism experiences is low; no particular type of experience preferred.

Local authenticity - Food and wine experiences are a tool for exploring a destination - its people and culture. Highly interest in: authentic local produce, street food, local and farmers’ markets, regional specialties, eating/drinking in spectacular surroundings.

Traditionalists - Interested in the ‘classic’ experiences: food and wine heritage, fine dining restaurants, wineries, food/wine tours, food/wine trails, events/festivals.

Generalists - Show no particular preference for types of experiences; moderate level of interest to wine and food.

Niche experiencers - Interested in specialized and more intensive food and wine experiences; expressed preferences for hands-on experiences, cooking courses, indigenous food experiences.

The group of local authenticity seekers is reported as most dominant in the report, while niche experiencers form the smallest share.

The only study that attempts to profile wine tourists in Bulgaria is the one ofDimitrov (2014), who states that the main share of wine tourists is in the 37-49 age bracket, with good knowledge of wine, looking for something new.

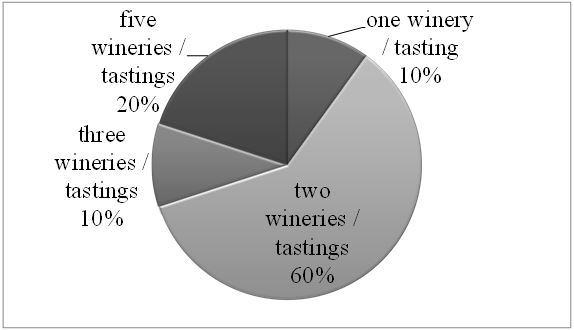

Another dimension of wine tourists’ behavior that can inform wine tour design is the number of wineries visited per day. A study on travel behaviors of wine tourists in Michigan’s Leelanau Peninsula identified an average of 3.91 wineries visited per day, while other attractions had a mean of 0.58 (McCole & Popp, 2014). While no other studies reporting the average number of wineries visited per day were found, an examination of wine tours offered by travel agencies in Italy and France reveal that the most common number is 2-3.

2. METHODOLOGY

In accordance with the two-fold objective of this study, the research process was divided into two stages, both based on content analysis (Figure 1). The first stage aimed at identifying the different types of wine tours (based on theme and included activities) and employed content analysis of numerous sites of specialized tour operators, travel websites such as Trip Advisor, and articles presenting rankings of best wine tours (e.g. “World’s Top Wine Tours” (Shoenfeld), “10 of the world’s greatest wine tours” (Trend, 2016) , etc.). The analysis included exploration of the main topic in the tours’ names and slogans, the activities included, the sites visited within the tours, and the overall emphasis in the text describing the offer. This part of the study was conducted between September-December 2016.

The second research stage was to a great extent informed by the findings of the content analysis described above. It was however focused on wine tours offered in Bulgaria and combined qualitative with quantitative approach. Starting with content study of the websites of specialized tour operators in Bulgaria in order to identify selected features of wine tours such as price, theme, geographical distribution, and duration, we have then tried to quantify them (using percentage and means where appropriate) so that the structure of this specific sector in the tour operator market in the country can be revealed. The most challenging aspect was to collect a sufficiently comprehensive list of wine tour offers as there is neither official nor non-official source containing the necessary information. It was therefore decided to search the internet using the keywords “wine tours in Bulgaria” (as well as their equivalent in Bulgarian) and then record the search results. This resulted in a pool of data containing details on tour operator name, link to the specific offer (as to avoid duplication of results), length of tour (in days), price, number of wineries visited within the tour, activities and attractions included in the tour programme, and wine regions where the tour takes place. A total of 63 wine tours were identified, offered by 24 different tour operators / travel agencies. The data was gathered in the period January-March 2017.

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

3.1. Types of wine tours

According to the Georgia Declaration on Wine Tourism, “Wine tourism facilitates the linking of destinations around the common goal of providing unique and innovative tourism products, whereby leveraging synergies in tourism development, surpassing traditional tourism subsectors” (UNWTO, 2016, p. 42). This trend is best represented in wine tours, which in recent years have demonstrated increasing richness of topics around which the experience is organized. Of course, this diversity is only possible through synergies.

The review of wine tour offers found on the internet has resulted in the following classification, based on the underlying tour theme:

Standard wine tours – usually includes visits to two or three wineries per day, no additional activities or attractions emphasized in the offer.

Wine & Culture tours: matching wine tasting with visits to cultural attractions.

Wine & Food tours – one of the most popular combinations, food ranging from local to gourmet.

Luxury wine tours – usually private or small group ones, with an emphasis on luxury transport and/or accommodation, and gourmet dining.

Responsible wine tours: the emphasis here is on organic / bio dynamic vineyards and wines, support of local communities, joint projects with local people and organizations, efforts for limiting the negative impact on the environment, close contact with local culture. The Responsible Wine Tasting section of responsibletravel.com currently includes 20 tours to 12 countries (Responsible Travel, 2017)

Transport-specific wine tours: This group includes tours that rely on less common means of transport to set apart from competitors. Usually this is highlighted in the name of the tour (Classic Convertible Wine Tours, Napa Valley Balloon Ride & Wine Tour Package, Perth’s Famous Wine Cruise, etc.). The variety of vehicles used includes limousine, hot balloon, helicopter, boat and others.

Active / adventure wine tours: combining wine tasting with adventure or sports experience (in softer or more extreme form). This type of products are aimed at physically active consumers, additional activities may be cycling, horse riding, trekking, or even skiing. The combination of skiing and wine is particularly popular in Argentina and Chile. Bike tours, on the other hand, are more common in Italy, France, Austria, and South Africa.

Innovative wine tours – these are tours that incorporate activities that are totally unrelated to wine, thus forming a unique selling proposition (USP). One of the most striking examples is the Murder Mystery Wine & Dinner Tour, offered in the Finger Lakes Region in the USA, where wine tasting is coupled with a crime-solving game, with clues being picked at the different sites visited within the tour (Experience! The Finger Lakes, 2017).

Connoisseur wine tours – targeted at people with profound knowledge and interest in wines, usually include lectures and discussions with professional enologists. Sometimes this comes at the expense of additional leisure activities and sightseeing.

Wine and nature tours – visits to wineries are coupled with nature-related activities such as bird-watching.

Wine and spa – a combination that is gaining increasing popularity.

The underlying trend in all identified types is the striving towards diversifying the offer, by combining wine with activities that suit individual needs and preferences of consumers.

It would be also interesting how these types of tours, identified through analysis of current supply, correspond to the demand-oriented profiling of wine tourists as described in the literature review. If we take as a basis the typology of the Australian tourism research team (Tourism Research Australia, 2014), which is one of the most popular, and as mentioned above – most elaborate as it encompasses both preferences for wine and leisure activities, we could presume that standard tours are targeted at traditionalists or connoisseurs, the wine and culture to traditionalists or low interest (depending on the wine experience / cultural sites ratio), and the wine and food ones – to niche experiencers. Responsible tours, too, would attract niche experience, but are more targeted at authenticity seekers. Wine and nature tours are strongly related to lifestyle and environmentally-conscious consumers – a category that is not included in the above-cited tourist typology. These assumptions are of course highly hypothetical and should be verified by further research, which would rather define a more detailed and up-to-date profiling of wine tourists.

3.2. Characteristics of wine tours in Bulgaria

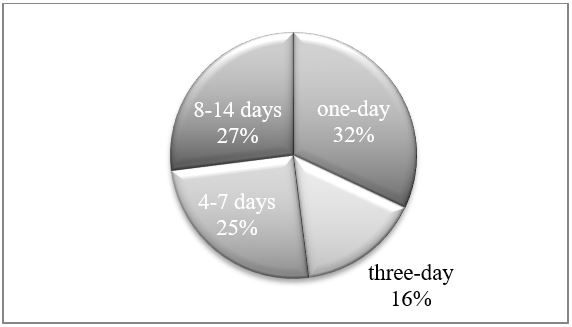

The following characteristics are based on data collected from 63 wine tours offered in Bulgaria and comprises information about the average price, the type of tour (standard, cultural, eco, etc.), the average number of wineries visited per day, and the wine regions included in the tour. The latter was used to find out if the tour operators/travel agents show preference for certain wine regions, which could both be a sign of their attractiveness and impact their tourism development. The programmes of included tours were also examined to obtain qualitative information regarding innovative practices.Fig. 1: Distribution of wine tours by durationpresents the distribution of the sample by tour duration.

In terms of tour duration, one day tours predominate, forming 32% of the total, followed by the longest type – 8-14 day tours with 27%. This is quite in line with the trend identified by a study on visitor behavior on the Setúbal Peninsula Wine Route, where the most common patterns that authors identify based on interviews with ravel agencies lie at the two extremes: one-day and longer than a week tours (Reigadinha & Cravidão, 2016). The share of 3-day tours is the smallest (16%), and 4-7 day tours account for 25% of the total number of tours included in the study.

3.2.1. Characteristics of one-day tours offered in Bulgaria

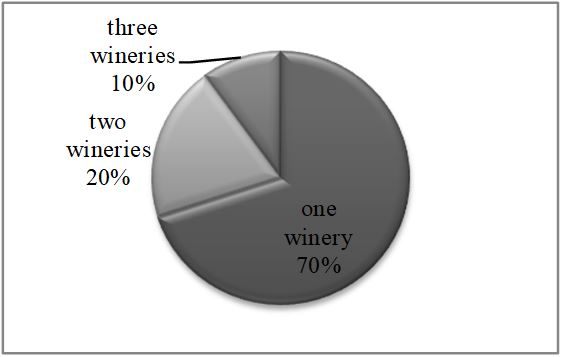

One-day tours are the most popular type of packages for organized wine tourism. The findings that follow are based on 20 different packages that were found online either on travel agencies’ websites or on Trip Advisor. The predominant number offer a visit to only one winery (Fig. 2) and the average number is 1,44, which is less than the common practice worldwide, where usually two and sometimes three or four wineries are visited within a day. The average price for a one-day wine tour is 109,45 Euro.

These figures are directly connected with the thematic structure of one-day tours – smaller numbers of winery visits are compensated by including cultural attractions. As shown in Table 1 only 25 percent of tours are standard ones – the predominant share blend wine and culture, and only 10 percent combine wine and food. All the standard tours are actually offered by two companies, the only large tour operator specializing in wine tourism in Bulgaria, and a smaller travel agency also specialized in wine tourism. In the group of wine & culture tours, only two ones stand out by offering local food and crafts, a visit to a bakery and peach brandy making. The only innovative product is the active wine tour, which includes snowshoeing in the mountain of Rila.

| Indicator | Number of wineries | Share |

| Theme | ||

| Wine and culture | 12 | 60% |

| Standard | 5 | 25% |

| Wine and food | 2 | 10% |

| Active | 1 | 5% |

| Wine regions included in the tour | ||

| Thracian Lowlands | 9 | 45% |

| Struma Valley | 9 | 45% |

| Rose Valley | 2 | 10% |

As seen inTable 1, there is no great variety in the destinations for one-day tours – the most popular ones are the Thracian Lowlands and the Struma Valley both accounting for 45% of the total number of tours, with only two packages (10%) offering trips to wineries situated in the Rose Valley. This could be most probably explained by the fact that these former two wine regions are at the closest proximity to and hence most easily accessible from the capital city of Sofia; in addition, the city of Plovdiv, which is one of the top cultural destinations in Bulgaria and the European capital of Culture 2019 is situated in the Thracian Lowlands. Moreover, the headquarters of the largest tour operator specializing in wine tourism are there. The Rose Valley wine region (the smallest in the country) is also located within a reasonable distance from Plovdiv and is very rich in cultural heritage.

3.2.2. Characteristics of 3-day wine tours offered in Bulgaria

Within this study, 3-day tours are the least popular ones – only 16% of the total number of identified offers are of this duration. The average price per day is 84.33 Euro, which is less than the average price of one-day tours. The average number of wineries visited per day is even smaller – 0.84. As presented inFig. 3, the predominant share of tours offer visits to only two wineries for within the whole trip, which reflects the pattern of one-day tours – but the average number is smaller because the last day of the tour is left for the departure journey and there are no activities included.

Wine and culture remains the most popular theme for three-day tours (Table 2), followed by standard tours focused mainly on wine. Wine and spa also seems to be a preferred combination, given the abundant spa resources in Bulgaria (one of the wineries features a spa hotel), and there is one tour that combines winery visits with walks in the nature, with an option of a bicycle tour (upon request). One of the wine&culture tours offers accommodation in a local farm, which is an example of a good practice, beneficial for both the local community and the visitor experience.

The number of wine regions featured in three-day tours is a bit larger compared with one-day tours. The Thracian Valley is the most popular one, represented in 58% of tours, followed by the Struma Valley. The Danubian Plain is included in only one of the tours, and so is the Rose Valley. In two of the packages there are visits to more than one region, which is made possible by the longer duration of the trip.

3.2.3. Characteristics of 4-7 day wine tours offered in Bulgaria

The average price per day is 103.95 Euro, which is above the figure for three-day tours and closer to one-day tours. The average number of wineries visited per day is 0.79, which is far less than world standards.

This type of tours exhibits the greatest variety of themes covered, ranging from “wine and culture” (the most popular) to active holidays combining wine and golf, or ATV driving to the Belogradchik Rocks (Table 3). Wine and culture still remains the most popular theme, accounting for nearly one-third of the total number of tours in this group.

Quite similar to the previous types of tours, there are two regions that receive the prevalent share of tours, and again these are the Thracian Lowlands and the Valley of Struma. The Danubian Plain is also present, accounting for 18 percent of the total.

3.2.4. Characteristics of 8-14 days’ wine tours offered in Bulgaria

The analysis of the 8-14 days’ wine tours offered in Bulgaria is based on 17 offers of tour operators/travel agencies, identified through the preliminary online search, forming more than one-fourth of the total number of wine tours included in the study. The longer duration of these tours predetermines some of their characteristics – more comprehensive experience and more emphasis on additional activities. Most of the tours are of the wine and culture type (Table 4), where wine tasting and visits to cultural attractions seem to have equal share in the tour programme – for most of the tours the cultural tourism aspect even seems to predominate. There is only one tour that has an explicit focus on local culture, and one tour which is marketed as a combination of wine and nature. The latter is the most innovative one in this group and features bird-watching.

In terms of wine regions included in the tours, there is a clear predominance of three regions – the Thracian Valley, the Danubian Plains, and the Valley of Struma over the Black Sea and the Rose Valley. This is also the only type of tours that feature the Black Sea wine region in the itinerary. As evident fromTable 4, most tours include more than one region; yet there are three packages where the whole trip is limited to only one wine region.

The average number of wineries visited per day for this type of tours remains very low – 0.74, which reflects the overall trend observed in the country. The average price per day is 90.25 Euro.

If we try to relate the supply characteristics of the wine tours market in Bulgaria with the wine tourist typologies presented in the literature review (the demand side)we could conclude that the market is still oriented towards the low interest and the generalist segments. Traditionalists, niche experiencers and local authenticity seekers are only catered by a very small number of offers, and this is extremely evident in longer tours (more than three days long), while in shorter ones, the first steps towards diversification and targeting to the more specialized segments is witnessed.

CONCLUSION

On a world scale, organized wine tours offered by travel agencies and tour operators are characterized by increasing diversity and products that cater to the needs and preferences of every segment possible – from the basic standard offer, through the responsible, the gourmet, adventurous, the connoisseur, to those who seek luxury.

Apart from identifying the latest trends in wine tour design, the present study gives a snapshot of the present situation in Bulgaria – an emerging wine destination, which has not yet uncovered its full potential. Apart from the slight differences in the four groups of tours, the sector shares a lot of common features, the most evident of which seems to be the small number of wineries included in the tour programme. The share of standard tours that feature at least two winery visits per day and have a strong focus on wine is significantly smaller than the wine&culture type, where the cultural aspect seems to overshadow the wine experience. The overall impression is that to a package that is purely cultural in nature, a visit to a winery is added so that it can be marketed as a wine tour. Innovative products are mainly represented by matching wine and nature-related activities; unfortunately, local cuisine and local wines are not given due attention. Connoisseur tours are also missing, thus ignoring a very important segment of the wine tourism market.

The average price per day ranges for different types of tours ranges between 80 to 110 Euro, the most expensive being one-day tours, which are also the most popular. It is however difficult to compare this with other wine destinations, unless a benchmarking tool is established, which would provide opportunities for comparing other product features too.

In terms of territorial distribution, there are two regions that benefit from organized wine tours – the Thracian Lowlands and the Valley of Struma, which is mainly due to their favorable location – close the capital. In recent years the capital city of Sofia has seen a significant rise in tourist arrivals, which strongly affected the demand for organized tours – especially one-day ones. The only type of tours that show a diversity of wine regions are the 8-14 day tours, which is quite predictable because longer duration allows a larger geographical spread.

On the whole, the sector of organized wine tours in Bulgaria seems to be in its initial stage of development, with only one larger specialized company operating on the market.