INTRODUCTION

The hospitality leadership competency model (HLCM) has been developed over time for leadership training and education (e.g.,Morris 1973;Tas 1988;Chung-Herrera, Enz and Lankau 2003;Shum, Gatling and Shoemaker 2018). However, before utilising for training and education, it is required that a theoretical model must be tested (Whetten 1989). The present literature shows scant empirical research on applying the HLCM model in the industry though calls have been repeated (e.g.,Testa and Sipe 2012;Shum et al. 2018). Additionally, because how employees perceive leadership can shape and influence the leadership of their managers (Kark and Van Dijk 2019), the perception of employees of leadership is critical but underexplored(Mistry et al. 2022). Thus, to continue using the HLCM, testing it on the key outcomes ofleadership, such as organizational commitment (Arici et al. 2021), is vital.

Prior studies have stressed that hospitality employees who commit to their organizations provide better service to the guests and contribute to sales growth (Bufquin et al. 2017;DiPietro, Moreo and Cain 2020). In using constructs other than the HLCM, studies have found that leadership determines the organizational commitment of employees and that organizations wanting committed employees need first to improve leadership (e.g.,Meyer et al. 2002;Kim and Brymer 2011;Kang, Gatling and Kim 2015;Lee and Ok 2016) Nevertheless, very few studies of this type have been conducted in developing countries (Yahaya and Ebrahim 2016), especially in Vietnamese hotels where, before the Covid-19 pandemic, uncommitted staff were leaving at an alarming rate (Le, Pearce and Smith 2018;Hang 2019).

In addition, organizations often prioritize their limited resources for training and developing the most needed competencies (Shum et al. 2018); thus, knowing which competencies are more salient in a particular context is mandatory for orienting their prioritization. However, due to minimal research on hospitality leadership in developing countries such as Vietnam (Elkhwesky et al. 2022), where hospitality is booming and training new managers is urgently needed (Bui and Giang 2022), this knowledge seems to be missing. In developing a model,Locke and Latham (2020) proposed, testing mediation and moderation effects is essential. To the HLCM model, the effects of either competencies or key mediators such as leadership consistency, which refers to how managers perform their duties in a consistent manner (Rogg et al. 2001), do not appear to have been tested there.

To address these gaps, the present study explores how the 10 competencies in the updated HLCM byShum et al. (2018) related toorganizational commitment, particularly affective commitment. The study then examines a mechanism whereby leadership consistency mediated the effect of team leadership (i.e., builds an effective team by clarifying roles, developing skills, and recognizing contributions), being the dominant competency, on affective commitment and how this effect was moderated by team size.

The study contributes to the theory around the HLCM by validating the model at the frontline level and especially in light of the crucial, yet unnoticed view of frontline (i.e., non-managerial)employees. The study quantifies the relationships between affective commitment and leadership competencies, especially team leadership via the mediating effect of leadership consistency. Finally, the study contributes to the literature new insights into how the understudied context of Vietnamese hotels shapes salient competencies on which some practical implications for hospitality employers, managers, and educators can be drawn.

1. LITERATURE REVIEW AND HYPOTHESIS DEVELOPMENT

The HLCM has been gradually developed with the cumulative contributions of many hospitality researchers and practitioners. Following the first study, which is often credited toMorris (1973), many studies have been conducted, mostly in western countries, by examining the perceptions of hospitality managers, educators, and students of highly demanded competencies (e.g.,Kay and Russette 2000;Chung-Herrera et al. 2003;Marinakou and Giousmpasoglou 2022).

A competency is a set of “observable and applied knowledge, skills and behaviors that create competitive advantage for an organization … it focuses on how an employee creates value and what is actually accomplished” (Nath and Raheja 2001, p. 26). Competencies are, most importantly, measurable and usable for training (Boyatzis 1993;Nath and Raheja 2001). This definition reinforces the view ofMorris (1973) andTas (1988) that competencies are essential skills and activities to perform a job. The competency model appears at the periphery in the broad leadership literature, which likely highlights leadership style theories (e.g.,Banks et al. 2018). However, the model has been implemented first in the tourism and hospitality industry in many nations (Van Der Wagen 2006) and has become a popular model in selecting and appraising hospitality managers (Gannon, Roper and Doherty 2015;Swanson et al. 2020).

In an initial research study of manager trainees in US hotels,Tas (1988) found 36 significant competencies, which were ranked in four groups of importance and categorized into human, management process, and professional factors. Since changes in the industry and the business environment require new competencies (Johanson et al. 2011;Sisson and Adams 2013), the pool of competencies has become large. For example,Chung-Herrera et al. (2003) extended earlier studies and suggested a pool of 99 competencies, which were classified into eight factors and, as a very rare study,Asree, Zain and Rizal Razalli (2010) tested and reported strong effects of this eight-factor-model on the outcomes of organizational responsiveness and performance.Sisson and Adams (2013) found 33 competencies grouped into soft, hard, and mixed competencies.Testa and Sipe (2012) identified up to 100 competencies and, thus, categorized them into 20 dimensions and three higher order factors, namely business, people, and the self. For hospitality management trainees,Raybould and Wilkins (2005) developed a framework of 52 generic competencies in nine groups. These large numbers of competencies and diverse categorizations make up a rich literature. Nevertheless, it becomes intricate to predict outcomes with a large number of competencies being predictors, whereas three or more observed variables measure each. This may explain why there is a lack of empirical testing of an array of competencies on the outcomes.

Recently,Shum et al. (2018) updated HLCM and parsimoniously identified 15 competencies that are equally distributed into business, people, and personal factors. They argued that it is essential to differentiate the competencies needed for different management levels since, by definition, competencies are job-specific. Hence, each level has its own competencies of priority, and this differentiation was supported in their study. Especially, they found that business competencies are required for director-level managers only, whereas developing personal and people competencies is most needed and should be prioritized for frontline managers. In personal leadership, Shum et al. (2018) identified five competencies: (1) acts ethically, (2) demonstrates emotional intelligence, (3) values and promotes diversity, (4) maintains a proactive learning orientation, and (5) communicates effectively. In people leadership, they identified five competencies: (1) manages conflicts, (2) delegates effectively, (3) leads team effectively, (4) coaches and develops subordinates, and (5) defines and achieves high performance (see pp. 62-63 ofShum et al.’s (2018) paper for the precise and complete definitions of these competencies). With a testable number of competencies and being level-specific, this updated model enables predictive tests and specific implications for each managerial level. It is therefore these above 10 competencies of frontline managers, which likely determine the commitment of their subordinates, that are being investigated in the current study. Identifying the expected competencies for frontline managers is essential to reduce the discrepancy between what has been taught in schools and what is expected by the industry, a gap that has been found in many studies being reviewed byMarneros, Papageorgiou and Efstathiades (2021).

As introduced above, the organizational commitment of employees, which is defined as “the strength of an individual’s identification with and involvement in a particular organization” (Porter et al. 1974, p. 604), is a key outcome of leadership.Organizational commitment has been conceptualized as having three components: affective commitment (a perceived attachment to the organization), normative commitment (a perceived obligation to stay), and continuance commitment (perceived costs of leaving) (Meyer et al. 2002). Affective commitment has been found to have the strongest relationships with both leadership and employee performance (Allen and Meyer 1990;Meyer et al. 2002;Yahaya and Ebrahim 2016), including in hospitality (e.g., Bufquin et al. 2017). Theoretically, the leadership-affective commitment relationship is supported. Drawing from social exchange theory,Aryee, Budhwar and Chen (2002) argued that the employment relationship is characterized by both economic exchange via a formal contract and social exchange via mutual expectations of behaviors. Therefore, beyond the obligations bound by the contract, employees perceiving positive behaviors of their managers are likely to respond with positive attitudes and behaviors such as affective commitment (Allen and Meyer 1990;Haar and Spell 2004). Hence, it seems that enhancing affective commitment is essential to improving employee behaviors and performance, and leadership is likely a potent enhancer (Meyer et al. 2002;Kim and Brymer 2011;Arici et al. 2021).

Empirical studies have also affirmed that hospitality employees working with better managers express higher affective commitment (e.g.,Kim and Brymer 2011;Nguyen, Haar and Smollan 2020). A few discrete leadership competencies, such as managing change, were found to significantly impact hospitality employee loyalty (Swanson et al. 2020), which is likely linked to their affective commitment. Empowering leadership, including components such as delegation, coaching, and team leading, has been found to exert a strong effect on organizational commitment (Raub and Robert 2013).Loi et al. (2015) also found ethical leadership to correlate with affective commitment strongly. The above evidence guides us to hypothesize that: Hypothesis 1: Leadership competencies will be positively related to affective commitment.

Managers possessing leadership competencies need to perform them in a reliable and timely manner; therefore, possessing competencies is necessary but still not sufficient to both fulfil their duties and generate expected outcomes. The theory of performance (Boyatzis 1993 2011) emphasizes that some managers will become fully competent leaders if they endeavour to utilize their competencies consistently as required by their duties. Therefore, the consistency of leadership performance of managers indicates their competencies. From this view,Boyatzis (1993) raised a major concern about managers who possess competencies but do not consistently demonstrate them due to, for example, a lack of work motivation. Therefore, Boyatzis joined Lazear, a labor economist, in identifying that both leadership competencies and the discretionary effort being put into consistently demonstrating them are essential for leadership (Boyatzis 1993;Lazear 2012).Rogg et al. (2001) similarly defined leadership consistency as the extent to which managers are “consistent in their treatment of employees and the articulation of organizational goals and policies” (p. 436). In light of the theory of performance (Boyatzis 1993 2011), a manager needs first to possess leadership competencies in order to be able to perform these competencies in a consistent manner; hence, we hypothesize the following.

Hypothesis 2: Leadership competencies will be positively related to leadership consistency.

Rogg et al.(2001) further argued that leadership consistency likely affects the attitudes and behaviors of employees and, ultimately, the effectiveness of organizations. Thus, it may be the consistency of leadership performance that eventually helps managers boost their subordinates’ commitment, retain them, and finally achieve good results. Studies have found that leadership consistency strongly relates to employees’ attitudes and behaviors such as job satisfaction, organizational citizenship behaviors, organizational commitment, and psychological well-being (Luthans et al. 2008;Ozyilmaz and Cicek 2015;Kim et al. 2019). Prior studies have also shown that leadership consistency mediates the relationship between servant leadership (Ozyilmaz and Cicek 2015), or team leading competency (Kaya et al. 2010), and the outcome of job satisfaction. These findings support the argument ofRogg et al. (2001) and drive us to propose that leadership competencies tend to strongly relate to leadership consistency, which may, in turn, improve employees’ attitudes and behaviors, and this mechanism will apply to affective commitment. Additionally, some competencies have been found to be more important than others by ranking them from the views of managers and educators (e.g.,Tas 1988;Kalargyrou and Woods 2011;Marinakou and Giousmpasoglou 2022). Hence, there tends to have a competency that is the most salient (i.e., dominant) in producing the outcomes. Together, it is possible that leadership consistency plays an intermediate role in the relationships between leadership competencies and affective commitment, and this mediating mechanism is especially worthy of exploration with the dominant competency. In light of the theory of performance and all of these above research findings, we hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 3: Leadership consistency will be positively related to affective commitment.

Hypothesis 4: Leadership consistency will mediate the relationship between the dominant competency and affective commitment.

2. METHODOLOGY

2.1. Sampling and data collection

In 2019, we contacted all upscale hotels in the top tourist hubs of Vietnam, the cities of Hochiminh and Vungtau, via their general managers or human resources managers. Seven hotels (two large three-star, two four-star, and three five-star plus) agreed to distribute our paper survey packages directly to all of their frontline employees (about 550 employees). The hotels had their own surveying procedures, but none had the involvement of the direct managers of frontline employees, which was to ensure confidentiality.

2.2. Participants

We received 236 usable surveys in sealed envelopes (a response rate of about 43%), mostly from typical departments (i.e., food and beverages, housekeeping, and front office). Table I presents the demographic characteristics of the participants and their managers.

2.3. Measures

Although associated scales were not specified byShum et al. (2018), all the defined competencies have their own literature from where scales can be found. We developed the scales following a deductive scale approach (Hinkin, Tracey and Enz 1997) in which validated scales in the literature can be used to operationalize the construct.Robinson (2018) also suggested that researchers can use an existing scale that best matches the construct. Besides, using such validated scales, instead of self-developed ones, provides face validity (Crawford and Kelder 2019). Because discrete constructs and scales are multiple in the broad leadership literature (Banks et al. 2018), we were able to pick 10 scales, most of which have been validated, that match the 10 competencies defined byShum et al. (2018) and are usable for a service industry such as hospitality (see Table II). Leadership consistency was measured with the 6-item scale byRogg et al. (2001). Affective commitment was measured with the 5-item scale byMeyer, Allen and Smith(1993).

To translate the English scales into Vietnamese, we adopted the back-translation method (Brislin 1970) with several rounds of translation-revisions by scholars. The questionnaire was further refined to the comments of three hospitality scholars and three hotel frontline employees. All the constructs, scales, reliabilities, and sample items are presented in Table II.

2.4. Control variables

Gender, age, and tenure were measured and subsequently controlled for in relevant analyses. Because leadership consistency may be affected by the manager’s age and gender, and by team size (i.e., the number of subordinates managed by a manager, measured in groups), we measured and then included these control variables in the stepwise regression analysis.

2.5. Control for Common Method Variance (CMV)

As suggested byPodsakoff et al. (2003), we controlled for CMV in both the design (e.g., using five and six-point Likert scales) and the analysis phases (e.g., inserting transitional sentences in the survey). To check for potential CMV bias, we ran Harman’s single factor test. A single factor with eigenvalues greater than 1 accounted for 39.8% variance in the dataset. Since this value is below the threshold of 50% (Podsakoff et al. 2003), CMV bias might present but would not misdirect our interpretation of results.

2.6. Scale Validation

Using AMOS, we tested the construct validity of the HLCM (with 10 measurement scales) by confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). After removing some items with low factor loadings, the final model fitted the sample relatively well with c2 (549) = 939.9 (p= .000), CFI= .94, RMSEA= .05, and SRMR= .04, whereas rival models fitted the data poorer. These values confirmed the construct validity of the measurement model. Of all 10 constructs, the average variance extracted (AVE) values were above 0.56, and the composite reliabilities (CR) were above 0.7 (see Table II), suggesting adequate convergence and good reliability, respectively (Hair et al. 2010). Additionally, all skewness values were between ± 1.3, whereas all kurtosis values were between ±2.1, suggesting acceptable normality of data (Byrne 2013).

|

Constructs/ Competencies | Scales |

Sample Items Following the stem “My immediate supervisor/manager…” | Average Variance Extracted (AVE) |

Composite Reliability (CR) |

| Acts in an ethical manner |

Ethical leadership (Haar, Roche and Brougham 2018),α = .89 | Makes fair and balanced decisions | .69 | .87 |

|

Demonstrates emotional intelligence | Wong and Law EI Scale (WLEIS) (Law et al. 2004), α = .83 | Has good control of their emotions | .65 | .85 |

|

Values and promotes diversity |

Values and Promotes Diversity (Shum et al. 2018) | Ensures that the workplace is free from discriminatory behavior and practices | .66 | .85 |

|

Maintains a proactive learning orientation | Learning Orientation (Kaya and Patton 2011), α = .88 | Sees learning new knowledge as a key skill | .68 | .86 |

| Communicates effectively | Communicates Effectively (Shum et al. 2018) | Clearly articulates a point of view | .66 | .88 |

| Manages conflict |

Conflict Efficacy Scale (Alper, Tjosvold and Law 2000), α = .92 | Effectively manages conflicts among team members concerning work roles | .60 | .88 |

| Delegates effectively | Perceived Delegation (Schriesheim, Neider and Scandura 1998), α = .84 | Gives me areas where I decide on my own, after first getting information from them | .64 | .84 |

| Leads effective teams |

Team leadership (Northouse 2016), α = .92 | Looks for and acknowledges contributions by team members | .58 | .84 |

|

Coaches and develops others |

Supervisory Coaching Behaviour (Ellinger, Ellinger and Keller2005), α = .94 | Provides me with constructive feedback | .56 | .84 |

|

Defines and achieves high performance |

Supervisory Knowledge of Performance (Ramaswami 1996), α = .93 | Can assess my job performance | .67 | .89 |

| Leadership consistency |

Leadership Consistency (Rogg et al. 2001), α = .89 | Follows through on commitments | -- | -- |

| Affective commitment | Affective Organizational Commitment (Meyer et al. 1993), α = .85 | This hotel has a great deal of personal meaning for me | -- | -- |

2.7. Analysis

To test the hypotheses, we used SPSS and the PROCESS macro. Because of multicollinearity, including all 10 leadership competencies together in a single regression equation may produce imprecise regression coefficients (Pedhazur 1997). Therefore, we used a stepwise regression procedure and all possible subsets regression approach (Pedhazur 1997;Kraha et al. 2012) to obtain a smaller but meaningful number of competencies (i.e., salient predictors). We ran two models with leadership consistency and affective commitment, each as the criterion. The control variables were included in all analyses.

3. RESULTS

Table III presents descriptive statistics and correlational results. All competencies were strongly and positively correlated with affective commitment (highest r= .38 for team leadership) and leadership consistency (highest r= .78, also for team leadership). All bootstrapped confidence intervals of the correlations (5,000 samples, 95% confidence) did not contain zero, with all p values < .01. These results support Hypotheses 1 and 2 and imply that all 10 competencies were likely to be strong but rival predictors of both criteria. Table 3 also shows that leadership consistency had the strongest correlation with affective commitment (r= .40 [.29,.51], p< .01).This correlation result supports Hypothesis 3.

Using stepwise analysis and all possible subsets regression, we found that leadership consistency was best and significantly predicted by the set of predictors involving (in descending order) team leadership, evaluation, conflict management, communication, and coaching. Team leadership and delegation, respectively, were found to be the best predictors of affective commitment. Consequently, team leadership, being the most salient predictor found in both regression models, was used to test the mediation model. Unstandardized coefficients and bootstrap confidence intervals (5,000 samples, 95% confidence) are reported with Confidence Intervals (CI) at Lower Limits (LL) and Upper Limits (UL).

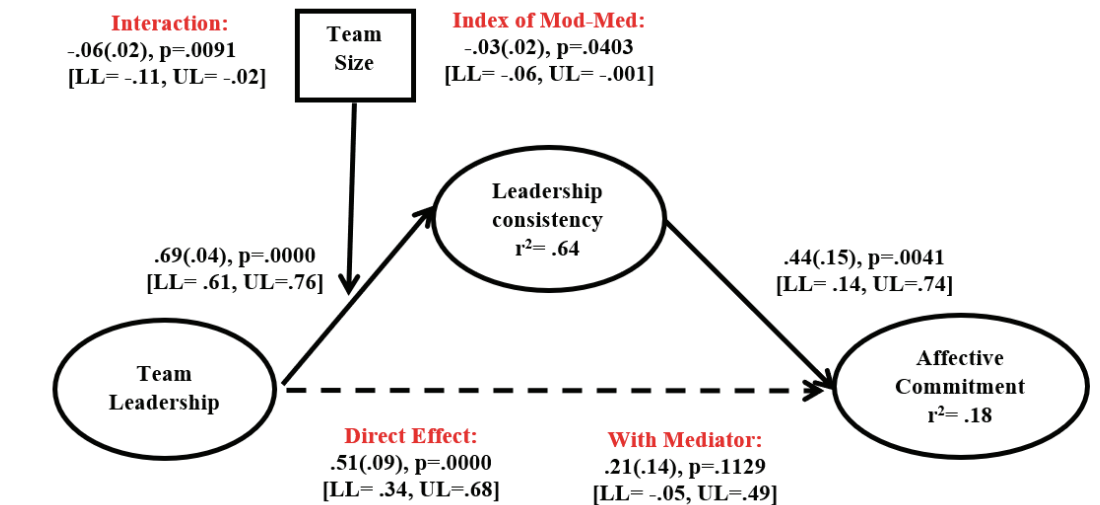

Using model 4 of PROCESS, we tested the mediation effect of leadership consistency. Team leadership was first found to be directly and significantly related to affective commitment (path c, or total effect: β= .51, p= .000 [LLCI= .34, ULCI= .68]). Being fully mediated by leadership consistency with the effect of the mediated path (path ab, or indirect effect: β= .30, [LLCI= .07, ULCI= .54]), the direct effect of team leadership on affective commitment dropped to (path c’, or direct effect with mediator: β= .21, p= .11, [LLCI= -.05, ULCI= .49]), i.e., insignificant. The mediation model explained 17% of the variance in affective commitment (R² = .17, F(4,228) = 11.9, p< .000) with insignificant and very slight effects from control variables, and 62% of the variance in leadership consistency (R² = .62, F(3,229) = 125.5, p< .000). This mediation mechanism implies that a leadership competency, typically team leadership, contributes to shaping leadership consistency, which subsequently influences affective commitment. Hypothesis 4 is supported.

Having found team leadership to be the dominant competency plus its strong effect on affective commitment via leadership consistency, we explored further the moderating role of team size as it has been argued that team leadership needs to be viewed together with team size (Day, Gronn and Salas 2006). Comparing to smaller teams, leaders of larger teams may have less opportunity for coaching, recognizing, supporting subordinates as well as maintaining effective relationships with all of them (Yukl 2013), thus team members may receive fewer resources and perceive less support from their leaders (Pearce and Herbik 2004). Using several team theories such as understaffing theory,Weiss and Hoegl (2016) proposed that team size may modify the relationships between communication, as well as role conflict in the team, and team performance. All of these authors stressed that the effect of leadership on its outcomes would depend on team size, and this may apply to frontline managers. In light of these theoretical propositions, the detected effect of team leadership on leadership consistency in the mediation model (path a:β= .69, p= .000, [LLCI= .61, ULCI= .76]) signalled us to conduct a post hoc analysis to explore how team size may change this effect. Therefore, we tested the moderation role and effect of team size in the moderated mediation model 7 of PROCESS. The results obtained from this model are summarized and presented in Figure I.

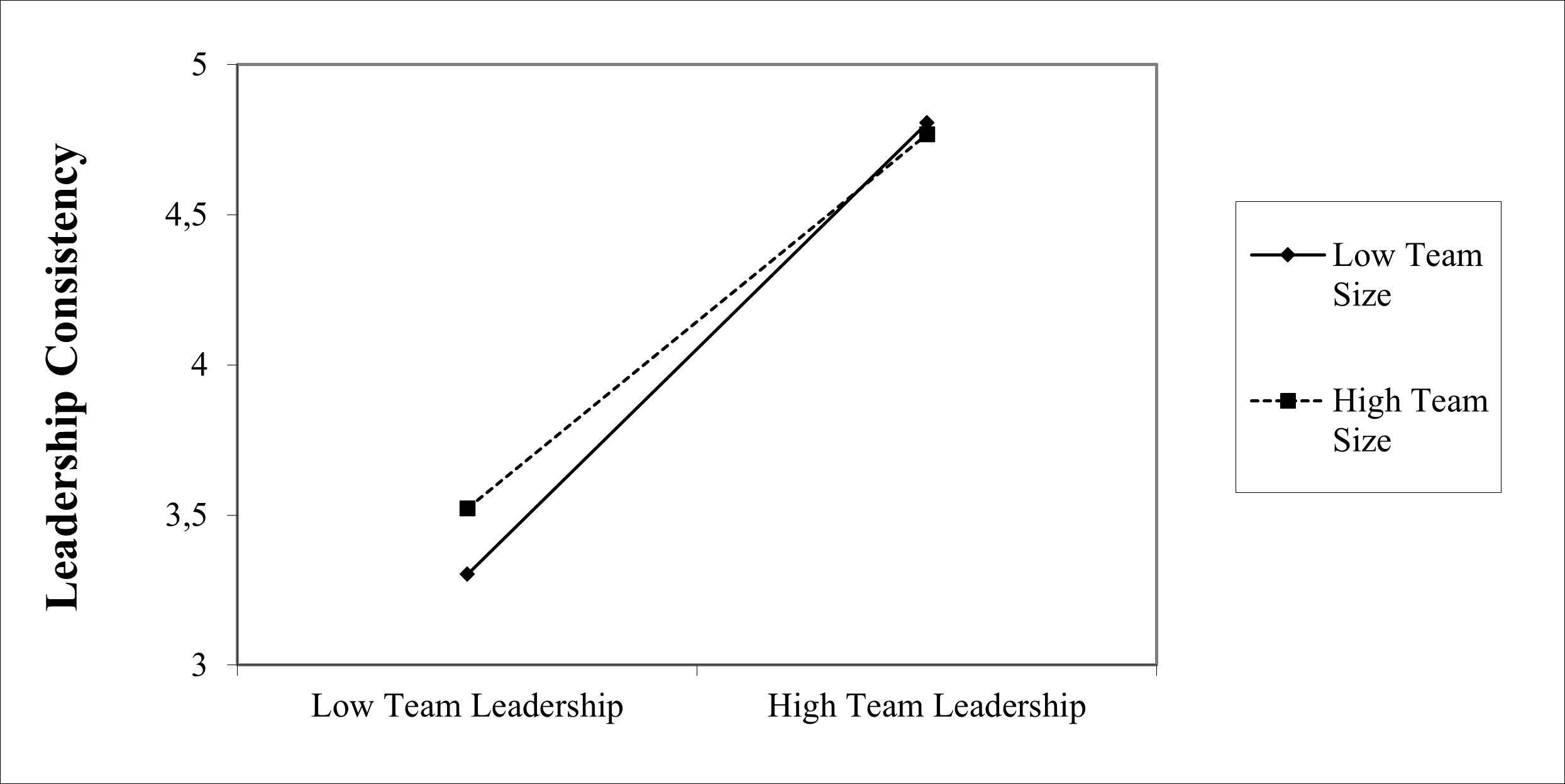

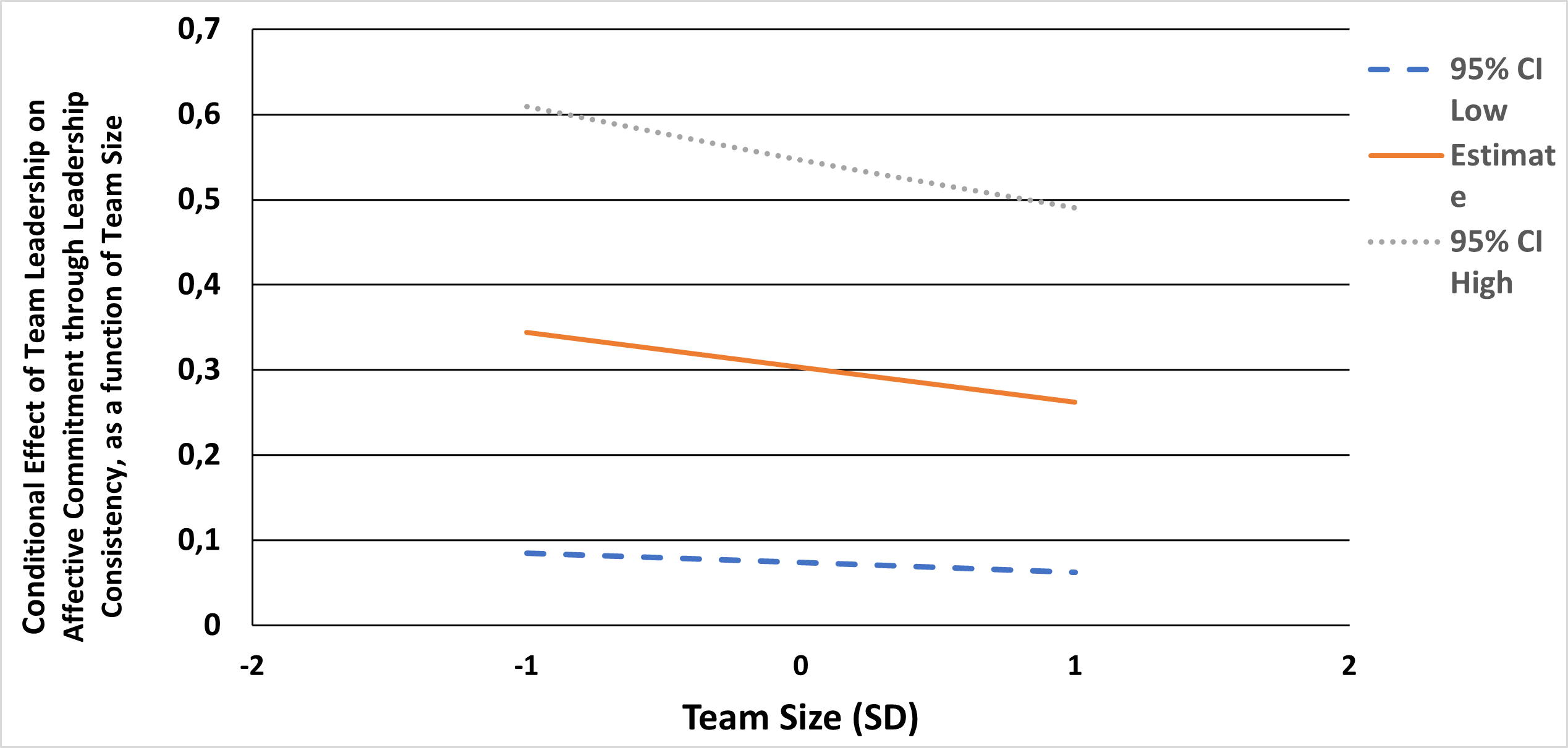

There was a small, but not hypothesized, interaction effect of team leadership and team size (β= -.06, p= .009, [LLCI= -.11, ULCI= -.02]) on the mediated path from team leadership to leadership consistency. This interaction effect accounted for 1.1% variance in leadership consistency (Rchange = .011, Fchange= 6.9, p= .009). As Figure II illustrates, for small (i.e., low) team size, team leadership correlated more strongly to leadership consistency (β= .78 at SD= -1, p< .000) whereas large (i.e., high) team size seemed to weaken their correlation (β= .59 at SD = +1, p< .000). Thus, the effect of team leadership on leadership consistency was stronger if team size was smaller. Figure III shows the conditional effect of team leadership on affective commitment through leadership consistency as a function of team size. At larger team size, team leadership had a slightly weaker effect on leadership consistency, which in turn exerted a weaker effect on affective commitment. This interaction effect weakened the conditional indirect effect of team leadership on affective commitment through leadership consistency by a small, negative moderated mediation index at (β= -.03, [LLCI= -.06, ULCI= -.001]). Additionally, this significant effect should ease the risk of severe CMV in the data because interaction effects are unlikely to be detected with data affected by CMV (Podsakoff, MacKenzie and Podsakoff 2012 ). Overall, model 7 explained 18% of the variance in affective commitment and 64% of the variance in leadership consistency, thus suggesting a small, but meaningful improvement compared to the mediation model 4.

4. DISCUSSION

We aimed to explore the relationships among the 10 leadership competencies of hotel frontline managers in the updated HLCM and leadership consistency and affective commitment. The results indicate that employees who perceived a higher level of leadership competencies showed stronger commitment toward their hotels, implying strong relationships between leadership competencies and affective commitment, especially in the high turnover context of Vietnamese hotels. The results also show that team leadership was the dominant competencyand that the relationship between team leadership and affective commitment was fully mediated by leadership consistency, but this mediating effect was, without prior hypothesizing, moderated by team size. Overall, the results support all hypotheses and meet our objectives for this present study. The findings potentially make some critical contributions and implications as follows.

First, the present study clarifies that the 10 leadership competencies in the updated HLCM are likely crucial factors that enhance the commitment of hospitality employees towards their organizations. The result is consistent with other studies in the hospitality industry, which, however, adopt leadership constructs other than the HLCM (e.g.,Kim and Brymer 2011;Kang et al. 2015;Lee and Ok 2016). The finding in a less studied context such as Vietnam extends the literature aroundhospitality leadership and organizational commitment, which, to date, has been mostly covered in developed countries (Meyer et al. 2002;Yahaya and Ebrahim 2016;Elkhwesky et al. 2022).

Second, and in line with the study ofKalargyrou and Woods (2011), this study confirms the dominant role of team leadership at the frontline level. The results suggest that team-leading skill is significant in creating employee attachment to their teams and their organizations. Moreover, the mediating role of leadership consistency implies that leadership outcomes such as employee commitment would not meet expectations if leaders do not put effort into performing their possessed leadership competencies consistently. The finding highlights the process whereby leadership behavior produces expected outcomes via leadership consistency.Such finding also supports the theory of performance (Boyatzis 1993 2011), the personnel economic approach to leadership (Lazear 2012), and the arguments ofRogg et al. (2001) discussed above, which propose the mediating role of leadership consistency in the leadership process.

Third, this study sheds light on how team size could exert a nuanced influence on leadership consistency and affective commitment. The study confirms the moderating role of team sizeas proposed (e.g.,Yukl 2013;Weiss and Hoegl 2016), which has received minimal research attention (Cha et al. 2015). Our finding is in line with a few studies that found the moderating effects of team size in the leadership process (Cha et al. 2015;Kim and Vandenberghe 2017;Yuan and van Knippenberg 2022), especially in the relationship between team leadership and team innovation (West et al. 2003) or team performance (O’Connell, Doverspike and Cober 2002). These studies, however, have been conducted in the fields other than hospitality and adopted other leadership constructs. Thus, our study adds knowledge around the role of team size as a critical contextual factor of the HLCM. Such contextual understanding is essential for not only explaining the phenomenon and its operation better but exercising it smoothly in each context.

Fourth, according toLocke and Latham (2020), a model can be collectively developed by many steps, including essential steps such as defining the focal concepts, creating measures, identifying key outcomes, mediators, and moderators. The HLCM has been built with many studies; however, most of them have likely focused on identifying, defining, and ranking key competencies. The present study fulfils some remaining steps, including (1) synthesizing and validating a leadership competency measure for the frontline level, (2) measuring the effects of leadership competencies on affective commitment, and (3) identifying leadership consistency as a mediator and team size as a moderator. These fulfilments likely contribute to developing the HLCM to be a tested, thus ready-for-use model. In addition, our validation of the HLCM with 10 integrative competencies possibly extends its prospect to be an inclusive leadership model. The findings contribute to filling the gap in studying mediators and moderators in hospitality leadership research (Elkhwesky et al. 2022) and help shape the nomological network of leadership competencies.

The findings support the suggestion ofShum et al. (2018) and imply that, for frontline managers, training efforts should be put into people leadership competencies. The dominant role of team leadership implies that hospitality organizations, especially in Vietnam, should particularly put more effort into training team-leading skills for their frontline managers. Besides, hospitality schools, which have probably overtaught conceptual and analytical skills but undertrained people skills (Raybould and Wilkins 2005), may need to refocus their curricula.International hotel chains struggling with a high failure rate of expatriate managers may need to consider the training of a set of high-priority competencies in the host country for those managers (Mejia, Phelan and Aday2015). The set of salient competencies in Vietnam identified by the present study, including team leadership, delegation, evaluation, conflict management, communication, and coaching, may inform such training in this host country.

The mediating role of leadership consistency suggests that the assignment of managers who possess the required competencies is still insufficient to enhance the organizational commitment of employees, and human resource departments should continuously support these managers to put enough effort into performing their competencies. A lack of work motivation of these managers, for instance, needs to be frequently diagnosed and, subsequently, rectified with appropriate remedies. Such on-the-job support is much needed since, as observed byBoyatzis (1993), organizational efforts have been put too much on leadership training and development but too little on encouraging and ensuring managers to enact their role consistently. The moderating role of team size in the leadership process implies that there tends to have an optimum team size for each frontline manager, and this needs to be carefully considered in planning and developing human resources in hotels.

Dopson and Tas (2004) proposed the utilization of competencies for curriculum development in hospitality schools. Our findings suggest that the adoption of the HLCM for leadership training may have considerable potential, and it should be utilized with more confidence in both hospitality organizations and schools. Such a common utilization may reconnect leadership practice in the industry, which demands leadership competencies, with academic research, which has been otherwise focused on leadership styles (Swanson et al. 2020). Industry-driven training in hospitality schools is decisive to mitigating the existing deviation between what is taught there and what is needed by the industry (Aguinis, Yu and Tosun 2021). Finally, prospective and current hospitality managers may benefit from being trained in leadership competencies that are required in their jobs, especially the competencies that are highly valued by the subordinates, such as team leadership or performance evaluation.

5. LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE RESEARCH

Our study has some limitations which imply more and better research is needed in the future. The cross-sectional data hindered us from making a stronger claim on a causal path from team leadership through leadership consistency to affective commitment though support for this path presents in the literature (e.g.,Pearce and Herbik 2004;Yuan and van Knippenberg 2022). As with many competencies, the relatively small sample size also obstructed us from using a more precise technique of analysis such as SEM, and using it for building a second-order CFA model. The sample came from hotel frontline employees in two Vietnamese cities, which limits the generalization of our findings.

Our study made an initial probe, and its results encourage future research investigating objective, but confidential leadership outcomes such as guest satisfaction, productivity, or turnover rates. Such research will potentially expand the nomological network around leadership competencies. We suggest that a better research design is favourable, such as obtaining time-lagged or multiple source data. Replicated but modified research can also be done with middle and top managers, in other hotel ratings (i.e., three-star and below) or types of accommodation (e.g., cruises), or other service sectors such as travel or aviation. This research can be extended to other non-western countries to get insights such as whether or not the model ofShum et al.(2018) is further confirmed and applicable or needs to be modified. Given the dynamics of the industry, adding new competencies into the model and justifying them, or identifying the potential prevalence of other competencies (e.g., ethical leadership) in different contexts could be research directions that are useful for hospitality education and management.

CONCLUSION

Running a hotel with uncommitted employees is undesirable but likely avoidable by improving and developing leadership with a sound leadership model. The HLCM has been proved to have industry-focused, multilevel, performable, and usable-for-training features. The present study adds another feature of the HLCM as being able to predict a key outcome such as affective commitment through a moderated mediation mechanism. The study provides early evidence that the HLCM is likely a valid model from the view of hospitality employees as the central stakeholder group in the leadership process, given that this model has been long, but solely built and justified by influential stakeholders such as researchers and managers. Also, by integrating core competencies such as team leadership and ethical leadership, the modelcould be further developed into a ‘full range’ leadership theory and deserves a better position in the leadership literature. These features and developments support the HLCM as a likely sound model and beneficial option for educating, practicing, and developing hospitality leadership, given the availability of many rival, but general (i.e., one-size-fits-all) leadership theories.Arici et al. (2021) also concluded that “industry-specific leadership might be needed to better motivate and retain employees in hospitality organizations” (p.15). Taken together, we suggest that both hospitality schools and organizations should utilize the HLCM as an alternative leadership model. While in normal operation, Vietnamese hotels may need to focus more on team-leading and delegation competencies to win the commitment of their employees.