INTRODUCTION

Job design is a crucial topic in management literature, and it has typically been approached from the top down, with managers designing employee job tasks (Lu et al., 2022). However, the emphasis on job design has evolved from manager-initiated schemes to employee-initiated initiatives (Tims & Bakker, 2010). Employees now play a more active and proactive part in redesigning and updating various areas of job tasks (Guo & Hou, 2022). This new role and integral bottom-up approach have been stressed in modern job design research (Tims et al., 2016; Lim, 2022). Employee-initiated job design is called “job crafting,” which means employees’ physical and cognitive modifications in their work or relational limits (Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001; Song et al., 2022). Changes in the shape, scope, or several job duties or relationships at work are referred to as physical changes, whereas a change in cognition is a change in how employees view their job (Chen et al., 2014). Job crafting allows employees to expand their job resources and deal with job demands, working in a more comfortable environment (Iqbal, 2016).

In recent years, job crafting has gained prominence in tourism and hospitality research (e.g., Cheng & Yi, 2018; Lu et al., 2022; Song et al., 2022). Employees in the hospitality industry are constantly asked to fulfil various changing customer needs, so they must develop their job tasks and adapt to them (Teng, 2019; Song et al., 2022). Accordingly, Cheng et al. (2016) stated that by using job crafting behaviours, employees could better comprehend the importance and purpose of their work and new job tasks, allowing them to be more enthusiastic about it and increase their job performance. Additionally, job crafting behaviour can reduce job burnout, resulting in employees fitting into their jobs (Kim et al., 2018). Hence, job crafting enhances positive fit perceptions, thus leading to high work engagement (Lim, 2022). Besides, Lu et al. (2022) investigated job crafting as a proactive behaviour that provides a quick-response activity to address hotels’ customer abuse. Although job crafting receives

great importance in tourism and hospitality research, to our knowledge, none have looked at how job crafting affects employees’ organizational commitment through the mediating role of person-job fit in hotels’ food and beverage department.

After lodging, the hotel food and beverage department is the second-largest department (Shaheen et al., 2018). However, food and beverage employees face several challenges, including long working hours, a lack of experience, job stress, job mismatch, and low wages, which cause high employee turnover and low levels of organizational commitment (Tantawy et al., 2016; Ismail et al., 2022). Therefore, food and beverage department employees should be encouraged to express difficulties and challenges in their jobs and be more proactive in changing their job tasks (Meijerink et al., 2020). Because working within formal job descriptions is no longer sufficient, employees are expected to take the initiative and contribute proactively to change the working environment (Guo & Hou, 2022). The job crafting approach seeks to transform the working environment into valuable experiences, in contrast to the conventional way of designing work tasks (Cheng et al., 2016).

Applying job crafting in hotels’ food and beverage department is expected to boost employees’ job fit (Nurtjahjono et al., 2020). Person-job fit refers to the compatibility of individual aptitude with job demands or a person’s desires with work attributes (Pelealu, 2022). Previous studies investigated the relationship between job crafting and person-job fit (e.g., Tims et al., 2012; Chen et al., 2014; Tims et al., 2016; Li et al., 2021). Job crafting allows employees to tailor their knowledge, skills, competencies, and preferences to their professions (Tims & Bakker, 2010). In their study of hotel employees, Cheng et al. (2016) discovered that job crafting improves employees’ job fit. Employees who participate in job crafting find more meaning in their jobs, enhancing their person-job fit (Bakker et al., 2012). The fit between the employees’ qualities and the job type could boost organizational commitment, as indicated by (Nurtjahjono et al., 2020). Organizational commitment refers to an employee’s strong desire to remain with a hotel, a readiness to work toward hotel objectives, and specific convictions and acceptance of the hotel’s goals and values (Raub & Robert, 2013; Utami et al., 2021). Person-job fit promotes organizational commitment and minimizes turnover (Chen et al., 2014). Hence, adopting job crafting will increase person-job fit, and the latter will enhance organizational commitment. Therefore, person-job fit mediates the relationship between job crafting and organizational commitment.

This study makes significant theoretical and managerial contributions to the literature on hospitality and tourism. Theoretically, despite the influence that job crafting has on employees, little research has been done on the hotel’s food and beverage department. Hence, this study expands the literature to include a study of to what extent employees of the food and beverage department in hotels practice job crafting and its impact on their job fit. Also, the current understanding of how job crafting affects organizational commitment is insufficient. Thus, by examining the mediating function of person-job fit in the relationship between job crafting and organizational commitment, this study adds to the body of literature. This study proposes effective ways for hotel managers to stimulate job crafting among food and beverage employees. For instance, this study recommends that food and beverage managers can boost job crafting by encouraging employees’ proactivity. Therefore, this study examines the relationship between job crafting and organizational commitment through the mediating function of a person-job fit. This study has three specific objectives:

To explore the impact of job crafting on person-job fit.

To investigate the effect of person-job fit on organizational commitment.

To test the relationship between job crafting and organizational commitment through mediating the role of

person-job fit.

The five critical parts of the current study are as follows: the study’s introduction is the first part. The second part reviews the literature about the study variables. The third part is about research methods, while the fourth is about research findings. The final part discusses theoretical and managerial implications, limitations, and future research.

For the first time, job crafting was proposed by Wrzesniewski and Dutton (2001); they pointed out that job crafting is employees’ physical and cognitive changes to their jobs. The adjustments that employees make can be in reshaping the boundaries of their job or just changing some job tasks (Polatci & Sobaci, 2018). The concept of job crafting comes with the same meaning as job redesign, but it differs in terms of the organizational form and the person responsible for the job design (Cheng et al., 2016). Traditionally, the organizational form of job design comes from top to bottom, from manager to employee in job duties (Guo & Hou, 2022). Because of problems such as lack of time, lack of organizational resources, and mismatch of the job with the person, only some employees can receive support from the manager (Chen et al., 2014). Hence, a new concept emerged to craft the job in its new organizational form, from the employee to the management (i.e., from the bottom up) (Lu et al., 2022). The central premise of the job demands-resources (JD-R) theory is that every workplace has particular elements connected to occupational stressors (Li et al., 2021). Job characteristics are classified as job demands or resources in the JD-R theory, which allows the organization of individual job characteristics into one of two broad categories (Tims et al., 2012). Job demands are those parts of the job that necessitate ongoing effort, either physically or mentally, and are thus linked to specific physiological and psychological consequences (Tantawy et al., 2016). In contrast, job resources are the beneficial elements of a job that can do

any of the following: (a) help attain work objectives; (b) lessen the demands of the job and the physiological and psychological costs that go along with it; and (c) promote personal development and growth (Han et al., 2022). Therefore, job resources are those features of work that assist employees in dealing with challenging job demands (Li et al., 2021). There may also be personal development possibilities (e.g., decision-making autonomy or proper feedback) (Tims & Bakker, 2010). Tims et al. (2012) applied the JD-R theory to job crafting. They divided job crafting into four types: (1) increasing structural job resources,

(2) increasing social job resources, (3) increasing challenging job demands, and (4) decreasing hindering job demands.

Firstly, the focus of increasing structural job resources is on individuals actively expanding their levels of autonomy, work variety, and career opportunities (Polatci & Sobaci, 2018). Secondly, job crafting involves self-initiated initiatives to access valuable social information sources. Examples include feedback from a supervisor or colleagues and supervisory coaching (Cheng & Yi, 2018). Although both types of job crafting involve actively attempting to improve job resources, they differ in whether they influence the job structurally or socially (Song et al., 2022). Thirdly, decreasing hindering job demands refers to employees reducing the number of job tasks by eliminating some of the tasks they find physically and psychologically demanding or by actively avoiding responsibilities that add to the overall burden of their job (Cheng et al., 2016). Finally, increasingly challenging job demands describe how employees may try to widen the scope of their work or mix and match jobs to make their work more complicated to keep things interesting and prevent boredom (Polatci & Sobaci, 2018). Modifying the degree of job demands is the focus of the third and fourth forms of job crafting (Tims et al., 2016). Both challenge and impediment demands necessitate physical or psychological effort on the part of the employee to meet them (Xia et al., 2022). The challenge demands are linked to learning and success, whereas the hindrance demands are linked to stress (Tims et al., 2016).

Job crafting and person-job fit

Person-job fit is the harmony and suitability of the employee and work environment (Iqbal, 2016). In other words, the person- job fit aligns job requirements with employee knowledge, skills, and talents (Griep et al., 2022). According to person-job fit, employee qualities and work environment conditions must match or be compatible (Tims et al., 2012). Compatibility refers to how well the work benefits employees and organizations, resulting in organizational commitment (Pelealu, 2022). This compatibility is determined by two main factors: (1) how well employee goals and values may be met by the organization and

(2) how well employee skills and work requirements are compatible. Therefore, the person-job fit matches an employee’s skills,

goals, values, and requirements (Nurtjahjono et al., 2020).

Previous studies investigated the relationship between job crafting and person-job fit (e.g., Tims et al., 2012; Cheng et al., 2016; Griep et al., 2022). Participants in job crafting experience greater job satisfaction, improving their person-job fit (Bakker et al., 2012; Cheng et al., 2016). In a survey of employees from several industries, Niessen et al. (2016) found a significant association between job crafting and person-job fit. According to Tims et al. (2012), when structural and social job resources are optimized, employees will fulfil job requirements and fit well into their positions. Their independence at work and career opportunities are improved by increasing structural resources. Constructive feedback from managers and coworkers helps employees create and feel a positive environment that encourages growth and teamwork, and employees are more proactive regarding increasing social functional resources (Kim et al., 2018).

As a result, employees can meet the demands and challenges of their jobs by making the most of their skills and abilities (Cheng & Yi, 2018). For example, employees are creating more rigorous job demands that might result in better-aligned abilities or preferences with the job when an employee wants to use more abilities or learn new skills (Cheng et al., 2016). However, when employees’ job demands are too much to handle because they lack the necessary knowledge, skills, or talents, the job demands might be reduced proactively (Tims et al., 2016). Thus, this proactive activity will re-establish the balance between job demands and an employee’s talents. As a result of these job crafting processes, employees’ knowledge, skills, and talents better fit with the job’s resources and demands (Griep et al., 2022). Therefore, we argue that when food and beverage employees engage in activities related to job crafting. Their efforts to increase structural and social job resources, raise challenging job demands, and decrease hindering job demands are more likely to fit their jobs. Consequently, food and beverage employees are more likely to have an excellent person-job fit when job characteristics are aligned with their personal needs and talents. Based on a prior discussion, the following hypotheses are listed:

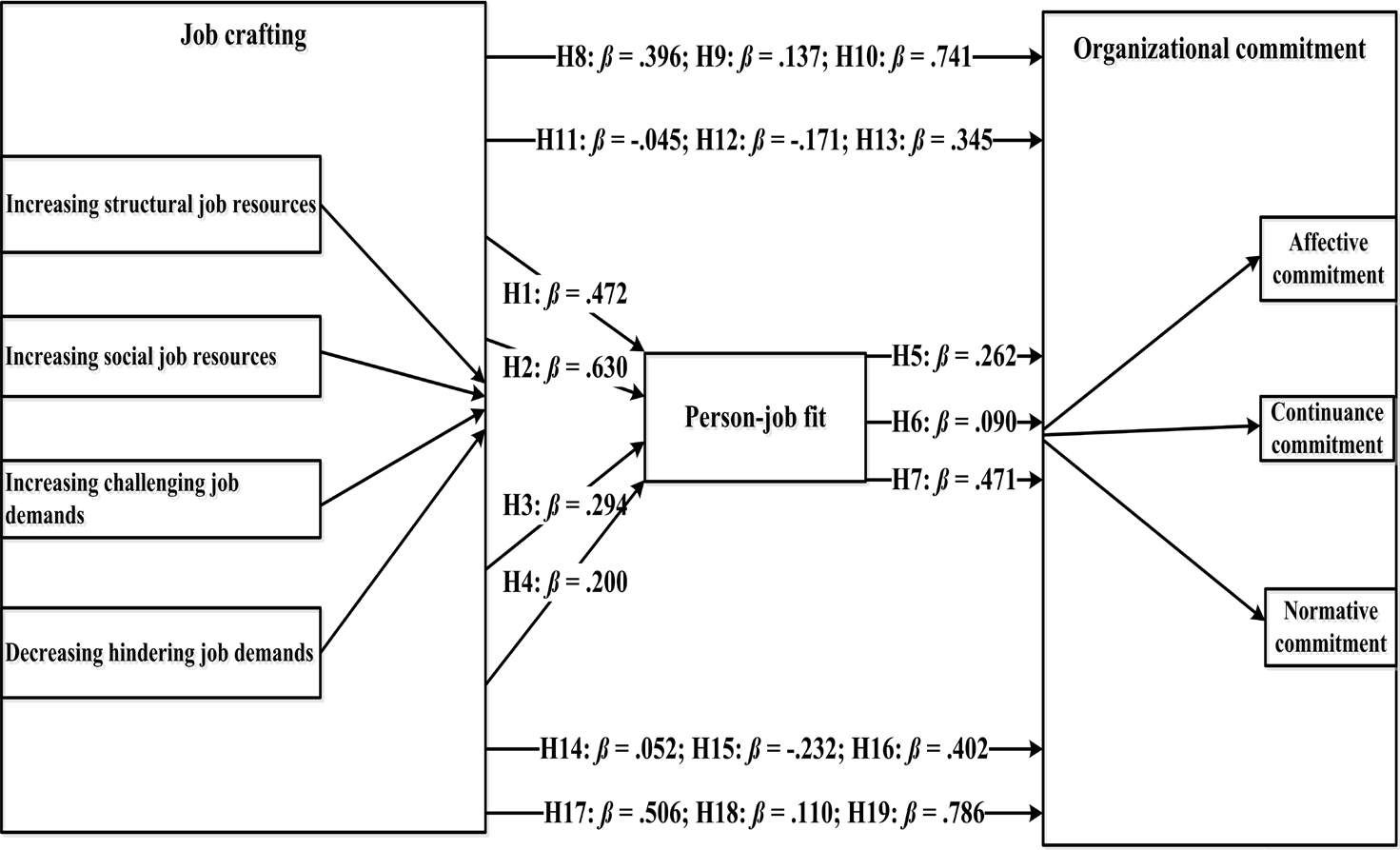

H1: Increasing structural job resources has a direct influence on person-job fit. H2: Increasing social job resources has a direct influence on person-job fit.

H3: Increasing challenging job demands have a direct influence on person-job fit. H4: Decreasing hindering job demands has a direct influence on person-job fit.

The relationship between person-job fit and organizational commitment

Organizational commitment is the firm belief and intention to identify with organizational values, devote to and stay with the organization and not want to leave work (Mustafa et al., 2022). In other words, organizational commitment is a desire to protect, work toward, and accept the goals and values of a particular organization (Utami et al., 2021). Allen and Meyer (1996) divided organizational commitment into three dimensions. Firstly, affective commitment is the term used to describe

an employee’s emotional connection to, identification with, and involvement in the organization (Nurtjahjono et al., 2020). Secondly, continuance commitment denotes recognizing the costs of leaving the organization (Raub & Robert, 2013). In other words, employees do not want to quit their jobs despite the potential losses associated with leaving the organization. Finally, normative commitment relates to employees’ perceptions of their obligations and responsibilities to the organization. It is a moral component of organizational commitment (Pelealu, 2022). Due to the organization’s investments and expenditures for the employees’ personal development and technical training, the employee feels bound to the company. This situation encourages employees to stay with the company and bid them normatively. Normative commitment also dramatically influences the successful performance of obligations (Raub & Robert, 2013).

Previous research indicated that person-job fit and organizational commitment have a significant association (e.g., Chen et al., 2014; Nurtjahjono et al., 2020; Guo & Hou, 2022). Employees with a better person-job match perform better than those with a lower match because they are more emotionally attached to the organization, demonstrating an unwavering commitment to its success (Guo & Hou, 2022). Person-job fit promotes job responsibility, performance, work satisfaction, and continuous commitment and minimizes turnover (Chen et al., 2014; Nurtjahjono et al., 2020). Therefore, we argue that when the food and beverage employees have a good job fit, they will emotionally commit, their turnover will be reduced, and their normative commitment will be improved with their hotels. Based on a prior discussion, the following hypotheses are listed:

H5: Affective commitment is directly impacted by person-job fit. H6: Continuance commitment is directly impacted by person-job fit. H7: Normative commitment is directly impacted by person-job fit.

The mediating role of person-job fit in the job crafting and organizational commitment relationship

Using JD-R theory as the theoretical framework, our study states that organizational commitment is one of the possible outcomes of job crafting via the mediating role of person-job fit. Employees feel energized, inspired, and independent when they can craft their jobs using job resources and challenging job demands (Lim, 2022). Job crafting helps employees seek assistance and advice from coworkers and managers concerning their jobs to expand their social resources (Lu et al., 2022). This point of view is founded on the idea that people naturally desire to interact with others around them. Strengthening social connections can help employees handle demanding job requirements and enhance their capacity for job demands (Tantawy et al., 2016).

Additionally, creating the challenges of the work demands helps increase employees’ chances to learn and grow (Teng, 2019). For example, employees can consider customer complaints as a chance to enhance their communication skills. Employees may have the space and possibilities to display and develop their abilities and find significance in their jobs if given this opportunity (Song et al., 2022). When employees have a sense of purpose in their work, they are more likely to be productive and motivated and may even take on new tasks and responsibilities (Meijerink et al., 2020). Thus, employees by crafting their jobs in such a way that they can utilize their skills and develop themselves to expand job resources, employees are more likely to feel that they have the ability to meet the demands of their work (Kim et al., 2018).

Moreover, employees are more likely to indicate job fit when they can boost their structural and social resources in addition to challenging job demands (Song et al., 2022). When there is a greater diversity of skill sets, more autonomy, and more learning opportunities, employees may feel more personal control over their jobs and are more competent and independent in their positions (Guo & Hou, 2022). Increased job demands that are more difficult to meet, such as expanding tasks or adding new assignments, would better match an employee’s strengths or interests with their positions when they try to use more abilities and learn new skills (Chen et al., 2014). Also, employees can reduce workload demands by proactively reducing tasks beyond their knowledge, skills, or talents (Lu et al., 2022). Hence, the fitness between an employee’s abilities and goals and the demands of their job may be restored with the help of these crafting improvements (Cheng & Yi, 2018).

Furthermore, job crafting is anticipated to result in high levels of person-job fit, which will benefit organizational commitment. Employees that are a good fit for their jobs possess the abilities needed to complete their tasks, which results in managerial recognition and respect, self-organizing support, and increased workplace autonomy (Griep et al., 2022). Person-job fit assists an employee to adapt within the organization, identifies the skill sets required for the work, and increases commitment to the position (Mustafa et al., 2022). Hence, these employees with a job fit seem to want to stay in the hotels for two reasons. First, they see their hotels as a place to use and advance their skills (Lim, 2022). Second, they engage in job crafting behaviors and do the work they enjoy creating a creative and challenging work environment (Menachery, 2018). The strong correlation between enhancing person-job fit and increasing organizational commitment may be crucial to the relationship between job crafting and organizational commitment. Because job crafting might enable employees in the food and beverage to tailor their jobs to suit their skills and requirements, they are more likely to shape their hotel commitment. In light of this, we anticipate that all types of job crafting will enhance person-job fit, which will favorably impact all types of organizational commitment. Based on the prior argument, the following hypotheses are listed below:

H8: Increasing structural job resources indirectly affects affective commitment through person-job fit. H9: Increasing structural job resources indirectly affects continuance commitment through person-job fit. H10: Increasing structural job resources indirectly affects normative commitment through person-job fit. H11: Increasing social job resources indirectly affects affective commitment through person-job fit.

H12: Increasing social job resources indirectly affects continuance commitment through person-job fit. H13: Increasing social job resources indirectly affects normative commitment through person-job fit. H14: Increasing challenging job demands indirectly affects affective commitment through person-job fit.

H15: Increasing challenging job demands indirectly affect continuance commitment through person-job fit. H16: Increasing challenging job demands indirectly affect normative commitment through person-job fit. H17: Decreasing hindering job demands indirectly affects affective commitment through person-job fit.

H18: Decreasing hindering job demands indirectly affects continuance commitment through person-job fit. H19: Decreasing hindering job demands indirectly affects normative commitment through person-job fit.

We presented the research model indicated in figure one depending on the previous review of the literature and hypotheses.

Figure 1: The conceptual framework

The research hypotheses were investigated by gaining data from Cairo’s five-star hotels’ food and beverage staff. The employees of the food and beverage departments of the five-star hotels in Cairo, Egypt, were chosen for various reasons. Firstly, food and beverage industry employees face significant difficulties such as job stress, low pay, and long working hours (Ismail et al., 2022). As a result, food and beverage industry employees should be encouraged to express difficulties and challenges in their jobs and be more proactive in changing their work tasks. Secondly, earlier research on job crafting looked at the study of hotels’ front-line employees (e.g., Chen et al., 2014). Finally, to our knowledge, there is little research on job crafting in the African hospitality sector.

Moreover, the research team contacted the human resource managers of 38 five-star hotels in Cairo and asked for their help with the research procedure to confirm respondents’ readiness to complete the questionnaires. Twenty-three hotels decided to participate by asking their food and beverage personnel to complete the questionnaires. Between November 2021 and February 2022, the questionnaires were distributed. As a result, four hundred and fifty questionnaires were sent in this study, and four hundred and ten (n = 410) valid questionnaires were completed and returned, resulting in a 91.1% response rate. Therefore, this study depends on convenience sampling to pick hotel food and beverage personnel who filled out questionnaire questions. By contrasting the responses of late participants to those of early responders, non-response bias was examined (Armstrong & Overton, 1977). A low chance of non-response bias is implied by the results, which showed no differences in gender ( x2 = 1.18, p >.05), age ( x2 = 1.21, p >.05), marital status ( x2 = 2.78, p >.05), education ( x2 = 3.58, p >.05), workers department ( x2 = 5.60, p >.05), and length of employment ( x2 = 6.39, p >.05).

Measures

This study relies on items from previous studies to ensure the content validity of the constructs. Job crafting with four subdimensions was adopted from research conducted by (Tims et al., 2012). The construct person-job fit was adopted from the work of (Donavan et al., 2004), and organizational commitment’s three factors were adopted (Allen & Meyer, 1990). After discussions with various food and beverage employees, the questionnaire was fine-tuned. The final form of the study questionnaire was separated into two major components. The first part asked employees to rate 39 items on a five-point Likert scale: from “1= strongly disagree” to “5= strongly agree”. The second part asked employees for profiling information (i.e., gender, age, length of employment, department, educational level, and social status). The 39 items are divided into three constructs: job crafting (21 items), person-job fit (3 items), and organizational commitment (15 items).

Data Analysis

The validity and reliability of job crafting, organizational commitment, and person-job fit measures were initially assessed using Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) (see Appendix 1 for the measurement items). Structural equation modelling was used to test the direct and indirect relationships. Additionally, this study used Average Variance Extracted (AVE) to evaluate the construct’s convergent and discriminant validity. Composite reliability (CR) and Cronbach’s alpha for each latent variable were also employed to examine the constructs’ reliability (Hair et al., 2019). The Sobel test is used to investigate the final indirect relationships in which a third variable (i.e., person-job fit) mediates the relationship between the independent (i.e., job crafting) and dependent (i.e., organizational commitment) variables (Abu-Bader & Jones, 2021). Besides, the structural fit of the proposed model was assessed using goodness-of-fit methods. Theoretically, if the chi-square (2) is considered unacceptable, the model is appropriate; nevertheless, this is frequently disregarded because the chi-square (2) is frequently reported as significant due to sampling size limitations and its sensitivity to the likelihood test ratio.

Table 1 indicates the profile of the employees working in the investigated hotels. The employees were (i.e., 68.3 percent) males and (i.e., 31.7 percent) females. The youth employees from 18 to 40 years were the bulk investigated percentage (i.e., 98.8 percent) and above the 40 years (i.e., 1.2 percent). Single employees had the most significant marital status proportion (i.e., 77.6 percent), while those who were married or married with children had lower percentages (i.e., 22.4 percent). Most employees had a higher education (i.e., 85.3 percent) in terms of education. The investigated departments’ employees were almost similar percentage (i.e., 54.9 percent) from hotels’ restaurants and (i.e., 45.1 percent) from hotels’ kitchens. Regarding the length of employment, most employees had work experience of one year up to 3 years (i.e., 57.6 percent). However, the others were from 3 years up to 6 years of work experience (i.e., 20.2 percent), 6 years or more of work experience (i.e., 17.8 percent), and job experience of less than a year (i.e., 4.4 percent).

Table 1: Respondents’ demographic profile ( n = 410).

Measurement model

Certain adjustment indices were recommended to improve the model fit because the initial model did not fit the data well. More precisely, four items were deleted: I attempt to limit my contact with individuals whose problems have an emotional impact on me “DHJD3”; At my motel, I do not even feel like a member of the family “AC3”; I do not worry about what would happen if I leave my job without a backup plan, even if it were in my favour “CC4”, I do not think it is proper for me to leave my hotel right now “NC2”). Therefore, the measurement model had a satisfactory model fit: 2 (15) = 524.453; p < .0001, 2/df = 1, goodness- of-fit index (GFI) = 0.93, adjusted goodness-of-fit index (AGFI) = 0.95, normed fit index (NFI) = 0.93, relative fit index (RFI)

= 0.97, incremental fit index (IFI) = 0.933, Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) = 0.91, comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.94, all of these exceeded the permissible limit of 0.90, and the root mean square approximation error (RMSEA) was 0.034, which was below the criterion of 0.05 (Hair et al., 2010).

Table 2: Measurement model analysis

|

Code |

ß |

CR |

α |

AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

AC2 |

.942 | |||

|

AC4 |

-.815 | |||

|

AC5 |

.907 | |||

|

Continuance Commitment |

.753 |

.815 |

.521 | |

|

CC1 |

.944 | |||

|

CC2 |

.504 | |||

|

CC3 |

.646 | |||

|

Normative Commitment |

.751 |

.820 |

.562 | |

|

NC1 |

-.840 | |||

|

NC3 |

.665 | |||

|

NC4 |

.546 | |||

|

NC5 |

.762 | |||

|

NC6 |

.886 |

Note: Alpha reliability (α), Composite reliability (CR), and Average Variance Extracted (AVE) all showed significance at ≤ .001 for all factor loadings.

According to the CFA results, the lowest value of CR and Cronbach’s alpha for all constructs was 0.73, which is higher than the minimum allowed value of 0.70 and indicates a good reliability level (see table 2). Additionally, the AVE values of all constructs are higher than the permitted minimum value of 0.50, representing great convergent validity (Hair et al., 2010). Moreover, each construct’s AVE was much higher than its squared correlation for each pair of components, demonstrating strong discriminant validity (see table three) (Hair et al., 2019).

Table 3: The measurement model’s discriminant validity

Note: The constructs’AVE values are shown in bold along the diagonal line, while the other values are the squared correlations between each pair of constructs.

Hypothesis testing

Figure 2: The structural model

The proposed hypotheses in a causal diagrammatic were tested using standardized path coefficients (ß), as indicated in table 4.

The results showed that none of the direct hypotheses was disproved. Table 4: Standardized structural model parameter estimates

The findings showed a direct relationship between job crafting dimensions and person-job fit. H1 accepted, increased structural job resources significantly affect person-job fit ( ß =.472, p 0.001). This finding demonstrates that employees in the food and beverage are constantly looking for methods to improve themselves to meet the demands of their jobs and fit in. H2 accepted, that increasing social job resources significantly impacts person-job fit ( ß =.630, p 0.001). This result means that employees in the food and beverage can form positive working connections that are appropriate for their roles. H3 accepted, increasing job challenge influences person-job fit ( ß =.294, p 0.001). The food and beverage staff have proactive behaviour that allows them to fit into their positions. H4 accepted, that decreasing undesirable job demands considerably impacts person-job fit ( ß =.471, p

< 0.001). The food and beverage staff are well organized, which allows them to cope with challenging job responsibilities and fit into their roles.

Table 5: Hypotheses Test Results for Indirect Relationships

Note: * P ≤ 0.05, ** P ≤ 0.001, *** P ≤ 0.000. Notes: Increasing Structural Job Resources (ISJR), Increasing Social Job Resources (ISoJR), Increasing Challenging Job Demands (ICJD), Decreasing Hindering Job Demands (DHJD), Person-job Fit (PJF), Affective Commitment (AC), Continuance Commitment (CC), and Normative Commitment (NC).

Further, the findings also revealed a direct effect between the person-job fit and organizational commitment dimensions. H5 accepted, person-job fit directly impacted affective commitment ( ß =.262, p 0.001). Employees in the food and beverage department have a high level of job fitness, which helps them solve their work difficulties challenges, and build emotional attachments to the hotel. H6 accepted, person-job fit directly affects continuous commitment ( ß =.090, p 0.001). This finding indicates that the employees’ abilities and skills are a good match for their job, lowering employee turnover. H7 accepted, person-job fit directly impacts normative commitment ( ß =.200, p 0.001). According to this research, employees who feel well-matched for their jobs are more likely to remain committed to their hotel.

The indirect hypothesis was evaluated in this study using the Sobel test (see table 5). First, the findings demonstrated that increasing structural job resources has a positive indirect association with all organizational commitment through person- job fit, which supported H8 ( P-Value = 0.000); supported H9 ( P-Value = 0.002); and supported H10 ( P-Value = 0.000). This result means that the newly acquired food and beverage staff’ skills and abilities help them fit the position, allowing them to continue working enthusiastically and committedly for their hotel. Second, through person-job fit, the findings revealed that increasing social job resources has a positive indirect relationship with all organizational commitments except (i.e., affective commitment), rejected H11 ( P-Value = 0.233); supported H12 ( P-Value = 0.000); and supported H13 ( P-Value = 0.000). This result illustrates that obtaining social support aids food and beverage employees in fitting into their jobs, allowing them to attach to their jobs and reducing turnover emotionally.

Third, through person-job fit, the findings revealed that there is a positive indirect relationship between increasing challenging job demands and all organizational commitment except (i.e., affective commitment), rejected H14 ( P-Value

= 0.052); supported H15 ( P-Value = 0.000); and supported H16 ( P-Value = 0.000). This result implies that the food and beverage employees are extremely proactive in learning about their positions, which helps them fit into their roles and increase their commitment to the hotel. Finally, the findings revealed a positive indirect relationship between decreasing hindering job demands and all organizational commitment through person-job fit except (i.e., continuance Commitment), which supported H17 ( P-Value = 0.000); rejected H18 ( P-Value = 0.076); and supported H19 ( P-Value = 0.000). This result implies that food and beverage personnel can deal with the issues unique to their jobs and hotels, allowing them to better fit into their roles and strengthen their commitment to the workplace.

Using the JD-R theory, we investigated the mediating role of person-job fit in the relationship between job crafting and organizational commitment. We first examined how job crafting dimensions affect food and beverage employees’ fit with their profession. We discovered that increasing structural and social job resources directly impacts food and beverage employees’ job fit. These findings indicate that the food and beverage employees can effectively understand and use their job resources and proactively increase their levels of autonomy, the variety of their tasks, and career chances. They also have a good working environment to ask their colleagues and managers for help to develop their capacities and professional competencies. These results agree with earlier studies (Tims & Bakker, 2010; Cheng et al., 2016; Song et al., 2022) that crafting job resources enables employees to match their knowledge, skills, abilities, and preferences to their positions. As a result, hotel food and beverage managers should always encourage their employees to practice crafting job resources (Teng, 2019). They can also support employees’ autonomy and encourage constructive communication to improve job fit (Meijerink et al., 2020).

Additionally, we found that demand crafting dimensions impact food and beverage employees’ job fit, though less so than their job resource crafting. These findings indicate that employees in the food and beverage department are attempting to craft job demands challenges to some extent. As a result, food and beverage employees should acquire some other fundamental skills in crafting job demands to improve their awareness about job tasks, integrate into their work environment, help them overcome challenges, and foster a greater sense of creativity (Kim et al., 2018; Ismail et al., 2022). In addition, these new crafting demands skills will assist them in effectively organizing and continuously enhancing their interpersonal communications skills (Tims & Bakker, 2010; Teng, 2019).

Secondly, we investigated the direct impact of food and beverage employees’ job fit and organizational commitment. We found that employees in the food and beverage department have considerable job fitness, which aids them in adjusting to the internal work environment and being loyal and emotionally attached to their hotels. These findings are in line with the result of recent studies; employees who are person-job fit have a high degree of competency and interact successfully in their work environment (Iqbal, 2016; Nurtjahjono et al., 2020). Hence, when the employees’ competency, capabilities, and resources are available from their hotel, job suitability and creativity in performing tasks are enhanced, and the employee can continue working (Teng, 2019). As a result, job fitness will help create significant links between employees and their hotels, affecting their commitment to the hotels (Pelealu, 2022).

Finally, we examined person-job fit as a mediating between organizational commitment and job crafting relationship. We discovered that increasing structural job resources indirectly affected all organizational commitment dimensions through person-job fit. These findings indicate that employees in the food and beverage can improve their professional abilities and skills by learning new things to adapt to their jobs, and their aptitude for problem-solving and satisfaction at work is boosted (Chen et al. 2014). Therefore, to increase employee commitment, hotel food and beverage managers should continue supporting employees to craft resources and develop their employment objectives (Menachery, 2018; Kim et al., 2018; Guo & Hou, 2022). For instance, they should value, respect, and assist employees in achieving their goals from work besides job tasks (Nurtjahjono et al., 2020).

Another finding is that increasing social job resources indirectly affects organizational commitment dimensions through person- job fit except (i.e., affective commitment). These findings demonstrate that receiving support and assistance from supervisors and co-workers helps food and beverage employees adapt and fit the job, allowing them to attach to the job, avoid leaving, and increase their level of commitment. Hence, employees with an active connection with their co-workers and the potential to flourish are likelier to be loyal and committed (Iqbal, 2016). Thus, hotel food and beverage managers should continuously provide a positive social atmosphere to increase employees’ enthusiasm and affective commitment to their jobs (Han et al., 2022).

We also found that increasingly challenging job demands indirectly affect organizational commitment dimensions through person-job fit except (i.e., affective commitment). These results indicate that the food and beverage employees are somewhat proactive and continually researching all aspects of their work. In other words, by crafting challenging job demands, food and beverage employees become more accustomed to their work and stay longer, increasing their attachment, job fit, and organizational commitment and reducing the likelihood of turnover (Lim, 2022). Hence, hotel food and beverage managers should constantly explain any job-related ambiguities, and they can encourage employees to be more proactive and innovative (Meijerink et al., 2020). Also, when employees understand all aspects of their professions, it is easier to modify or restructure job tasks and be ready for new tasks (Mustafa et al., 2022).

The last outcomes of this study indicate that decreasing hindering job demands indirectly affects organizational commitment dimensions via person-job fit, except (i.e., continuance commitment). These findings indicate that employees in the food and beverage can, to a certain extent, overcome some challenging workplace challenges, such as communicating with unfavourable people, streamlining and organizing some challenging duties, and lowering work pressure. However, hotel food and beverage managers should establish an environment where staff members feel like they belong and everyone has an equal chance at success to enhance continuance commitment (Teng, 2019; Song et al., 2022). Thus, employees in the food and beverage industry can handle all of the obstacles of their professions, improve job fit, and ultimately strengthen organizational commitment (Griep et al., 2022).

Theoretical implications

Prior hospitality and tourism literature studies have examined the relationships between job crafting and job engagement, burnout, customer service behaviours, and employee-robot collaboration (e.g., Cheng & Yi, 2018; Teng, 2019; Song et al., 2022). However, to our knowledge, no study has been conducted on the relationship between job crafting and organizational commitment via the mediating role of person-job fit in hotels’ food and beverage departments. As a result, this study’s findings present several theoretical implications that can be used to address this research gap. First, the outcomes of this study expand the research on job crafting in the food and beverage department of hotels. The results of this study indicate that the food and beverage department employees engage in acceptable levels of job crafting. Through job crafting practices, employees better understand all aspects of their jobs, maximize their aptitudes and skills, locate and develop more job resources, and interact effectively with co-workers and managers (Lim, 2022). They also develop a proactive attitude that allows them to change challenging job requirements and turn them into opportunities (Lu et al., 2022).

Second, the findings of this study support earlier research by showing a strong direct relationship between job crafting and person-job fit (Tims et al., 2016; Cheng et al., 2016; Cheng & Yi, 2018; Griep et al., 2022). According to the study’s findings, the food and beverage department employees engage in job crafting, enhancing their fitness for employment. The findings indicated that job crafting activities, as seen in boosting food and beverage employees’ social and structural resources, significantly impact their fitness for their positions. Third, the findings of this study contribute to the tourism and hospitality literature by investigating the role of person-job fit as a mediator in job crafting and the organizational commitment relationship. The findings of this study demonstrate that job crafting activities increased person-job fit, which in turn increased organizational commitment among employees in the food and beverage department of hotels. Through job crafting techniques, employees in the food and beverage industry have adapted to their roles, identified the skill sets required for the job, and engaged in the work they enjoy, which has enhanced their organizational commitment (Nurtjahjono et al., 2020; Lim, 2022).

Finally, this study model provides a thorough understanding of the effect of job crafting on job fit and organizational commitment in the hotels’ food and beverage department. According to the study model, rather than the traditional strategy, this study emphasizes the need to develop job design approaches from the bottom up, from the employee to the management (Cheng & Yi, 2018). According to this study’s findings, employees who receive the required knowledge and support from their managers can better themselves, improve their professional networks, and be more committed to their organizations (Lu et al., 2022). Theoretically, this research’s investigation of complex impacts is critical for developing job crafting research in tourism and hospitality.

Managerial implications

Hotels’ food and beverage employees encounter several challenges that affect their job fit and low levels of organizational commitment (Chukwu et al., 2019). There have been numerous studies by hospitality and tourism researchers to solve the problems facing food and beverage employees (Jang & Kandampully, 2018; Shaheen et al., 2018; Ismail et al., 2022). However, some researchers in the field of hospitality and tourism pointed out that the problem lies in how jobs are designed (Cheng & Yi, 2018; Teng, 2019). Song et al. (2022) argued that the design of jobs, since managers are the ones who design the tasks of employees, results in many difficulties, for example, many work requirements, some complexities in the tasks, and the inconsistency of the operating steps. Therefore, this study suggested job crafting, whereby employees of the food and beverage department design their job tasks proactively to help them and their managers discover the fundamental challenges they face and provide suggestions to solve them (Meijerink et al., 2020).

According to the results of this study, the food and beverage employees participating in job crafting fit with their jobs and have a reasonable degree of organizational commitment. However, this study found that food and beverage employees participated more in crafting job resources than crafting their job demands. Therefore, this study presents some managerial implications for food and beverage managers to enhance job crafting activities, especially crafting demands. Firstly, food and beverage managers should promote employee autonomy to encourage them to craft challenging job demands (Xia et al., 2022). As a result, they can simplify some aspects of their work, breaking tasks down into manageable steps and encouraging seeking feedback from managers and co-workers about job tasks (Kim et al., 2018).

Additionally, managers in the food and beverage might motivate their employees to work more independently on more challenging tasks to enhance their creativity (Tims et al., 2016). Secondly, valuing employees’ goals and preferences refers to employees constructing their employment in line with their interests and aspirations (Berg et al., 2010). Finally, hotels’ food and beverage should consider supervisory support, which refers to how much managers regard their employees’ contributions and are concerned about their well-being. A supportive environment for crafting is created by the supervisor’s strength and the support of the employee (Menachery, 2018). When employees believe self-initiated initiatives do not endanger their supervisors, they actively initiate changes in their jobs (Teng, 2019).

Limitations and further research

This study is not free from limitations and offers opportunities for further research. This study examined the relationship between job crafting and organizational commitment through the mediating role of person-job fit in the food and beverage department in five-star hotels in Cairo. Further research can study the extent of the differences between job crafting applications in different hotel types and ranks. In addition, further research could study the application of job crafting in other hospitality establishments (e.g., restaurants, cafes, and catering enterprises). Also, the impact of job crafting is not limited to person-job fit and organizational commitment. Thus, future research could study the impact of job crafting on different variables (e.g., job stress, turnover, burnout, and loyalty). Further, in developing countries, employees suffer from low income; therefore, the extent to which job crafting can increase their ability to accept their current job could be investigated. Finally, we suggest investigating the logic of job crafting co-creation, which will allow employers and employees to share their opinions about the job tasks.